Matthew Stirling

Matthew Williams Stirling (August 28, 1896 – January 23, 1975)[1] was an American ethnologist, archaeologist and later an administrator at several scientific institutions in the field. He is best known for his discoveries relating to the Olmec civilization. Much of his work was done with his "wife and constant collaborator" of 42 years Marion Stirling (nee Illig, later Pugh).[2]

Stirling began his career with extensive ethnological work in the United States, New Guinea and Ecuador, before directing his attention to the Olmec civilization and its possible primacy among the pre-Columbian societies of Mesoamerica. His discovery of, and excavations at, various sites attributed to Olmec culture in the Mexican Gulf Coast region significantly contributed towards a better understanding of the Olmecs and their culture. He then began investigating links between the different civilizations in the region. Apart from his extensive field work and publications, later in his career Stirling proved to be an able administrator of academic and research bodies, who served on directorship boards of a number of scientific organizations.

Early life and work

[edit]

Matthew was born in Salinas, California, where his father managed the Southern Pacific Milling Company. Most of his childhood days were spent on his grandfather's ranch where he first developed an interest in antiquity, collecting arrowheads and researching artefacts.

Stirling majored in anthropology under Alfred L. Kroeber, graduating from the University of California in 1920. His interest in the Olmecs began in about 1918, when he saw a picture of a "crying-baby" blue jade masquette, published by Thomas Wilson of the Smithsonian Institution in 1898. When he traveled to Europe with his family after graduation, he found the masquette itself in the Berlin Museum, and intrigued by the Olmec culture, took time to look at other specimens in the Maximilian Collection in Vienna, and later, in Madrid.

Stirling was a teaching fellow at the University of California during 1920–21. He then joined the Smithsonian Institution, as a museum aide and assistant curator in its Division of Ethnology at the National Museum. He worked there until 1925. He located several more Olmec pieces in the museum. During this period, he also obtained his master's degree in Anthropology from the George Washington University. He was later, in 1943, to receive a Doctorate in Science from Tampa University.

He excavated on Weedon Island for the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE) in 1923–24, and at Arikara villages in Mobridge, South Dakota, during the summer of 1924. Stirling resigned from the Smithsonian to lead a 400-member, Smithsonian Institution-Dutch Colonial Government, expedition to New Guinea in 1925. He conducted ethnological and physical anthropological studies among the indigenous peoples there, and collected a number of natural history specimens, which now form one of the most valuable collections in the National Museum.

He returned to take over as chief of the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnology in 1928. He retained the position until 1957, his title changing to director in 1947. He went to Ecuador in 1931–32, conducting ethnological studies of the Jívaro, as part of Donald C. Beatty's expedition. He also worked along the Gulf Coast, directing archaeological digs in Florida and Georgia.

In 1931, he met Marion Illig (1911–2001), who took a job as his secretary.[3] They married on December 11, 1933 and worked together for the next forty-two years, until his death. She accompanied him on all but one of his subsequent archaeological expeditions. They had a son and a daughter.[3][2][4] Matthew Stirling wrote that Marion was his "co-explorer, co-author and general co-ordinator."[3]

Stirling was intrigued by Marshall Saville's two 1929 reports, Votive Axes from Ancient Mexico. Subsequent discussions with Saville launched Stirling into a phase of his career which would be focused on what was then beginning to be called Olmec culture.

The Olmec

[edit]The Olmec were an ancient Pre-Columbian people living in south-central Mexico, in the modern-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco, from about 1200 BCE to 400 BCE. They are claimed by many to be the mother culture of every primary element common to later Mesoamerican civilizations.

The name "Olmec" means "rubber people" in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. It was the Aztec name for the people who lived in this area at the time of Aztec dominance, referring to them as those who supplied the rubber balls used for games. Early modern explorers applied the name "Olmec" to ruins and art from this area before it was understood that these had been already abandoned more than a thousand years before the time of the people the Aztecs knew as the "Olmec".

Stirling and history of the Olmecs

[edit]By 1929, Stirling had begun suspecting that the artifacts emerging out of Mexico belonged to a time much earlier than attributed to the Olmecs. From the BAE, he directed excavations in fringes of the area thought to be Maya. Matthew and Marion Stirling first visited Tres Zapotes in 1938.[3][2] They travelled to the western margin and concentrated on the Tres Zapotes site. He noted the position of the colossal head – surrounded by four mounds – and the presence of a vast mound group in the area. He interested the National Geographic Society enough to be granted funds for excavation. This began a sixteen-year association with the site.

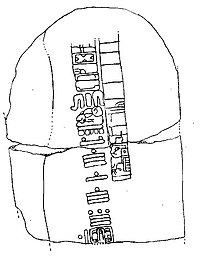

The bars and circles show the Maya-style long-count date of 7.16.6.16.18. The glyphs surrounding the date are what is thought to be one of the few surviving examples of Epi-Olmec script.

During excavations there in 1939, they discovered Stela C.[3][2] The top half of the monument was missing but the bottom half produced a Long Count date of ?.16.6.16.18. If the first digit was a "7" then the date would correlate to 32 BCE, a date considered by many to be too early for a Mesoamerican civilization. An "8" would mean a date of 363 CE. The Stirlings opted for the earlier date, to the consternation of many in the archaeological community.

They were proven correct in 1970, when the top half of Stela C was discovered, and the earlier date of 7.16.6.16.18, or 32 BCE, was confirmed.

He also led the first of several expeditions to San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán (1938), La Venta (1939–40) and Cerro de las Mesas (1940–41). In 1941, Stirling unearthed a large carved stone monument in Izapa, which he labeled Stela 5.

Stirling was unable to return to La Venta until 1942, due to World War II. When he did, he was to excavate several important artifacts. He then left for Tuxtla Gutiérrez to attend a conference on the Maya and Olmec cultures, one that was to become a defining moment in modern ideas about the Olmec. It was here that Miguel Covarrubias and Dr. Alfonso Caso first presented the case for the Olmec culture as being the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica, pre-dating even the Maya. Stirling supported their hypothesis, as he did Covarrubias in his interpretation of Olmec art. For example, Monument 1 at Río Chiquito and Monument 3 at Potrero Nuevo were, according to Stirling, the mythological union of a jaguar and a woman that produced "almost jaguar children".

It would be nearly 15 years before radiocarbon dating finally confirmed that the Olmec pre-dated the Maya. The Olmec culture is generally considered to have lasted from 1400 BCE until 400 BCE.

Other work

[edit]Stirling began searching for links between Mesoamerican and South American cultures in Panama, Ecuador, and Costa Rica from 1948 to 1954. He was also the chief organizer of the seven-volume Handbook of South American Indians.

He conducted excavations in the Linea Vieja lowlands of Costa Rica in the 1960s. Concentrating on tombs, he dug at five sites between Siquirres and Guapiles, and published a series of C- 14 dates ranging from 1440 to 1470 CE, and arranged much of the pottery excavated in an approximate chronological sequence.

In the Sierra de Ameca between Ahualulco de Mercado and Ameca, Jalisco, a large number of stone spheres, many of which are almost perfectly spherical, can be found. Their generally spherical shape led people to suspect they were manmade stone balls, called petrospheres, created by an unknown culture. In 1967, Stirling examined these stone spheres in the field. As a result of this examination, he and his colleagues hypothesized that they were of geological origin. A later expedition and subsequent petrographic and other laboratory analyses of samples of the stone balls confirmed this suspicion. Their interpretation of the data collected in both field and laboratory is that these stone balls were formed by high temperature nucleation of glassy material within an ashfall tuff, as a result of tertiary volcanism.[5]

Other positions held

[edit]Stirling was president of the Anthropological Society of Washington in 1934–1935 and vice president of the American Anthropological Association in 1935–36. He received the National Geographic Society's Franklyn L. Burr Award for meritorious service in 1939, 1941 (shared with his wife Marion) and 1958. He was also on the Ethnographic Board, which was the Smithsonian's effort to make its scientific research available to the military agencies during World War II.

After his retirement, Stirling was a Smithsonian research associate, a National Park Service collaborator, and member of the National Geographic Committee on Research and Exploration.

Stirling died in 1975, aged 78, after a period of illness associated with cancer.

Book collection

[edit]Marion Stirling donated around 5000 volumes from the Stirlings' library to the Boundary End Archaeology Research Center (earlier the Center for Maya Research).[6] They include a collection of scholarly pamphlets and reprints from the mid-19th century on, complete runs of the American Anthropologist (1881– ); American Antiquity (1935– ), Bulletins 1–200 and Annual Reports 1–48 of the Bureau of American Ethnology, and all the Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History.

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology

[edit]The museum, in the University of California, Berkeley, displays 165 Dyak and Papuan objects, including steel axes, basketry, arrows and wooden boxes, from Borneo, donated by Stirling.

Films by Stirling

[edit]Preserved at the Human Studies Film Archive, Suitland, Maryland:

- Exploring Hidden Mexico – Documents excavations at La Venta and Cerro de las Mesas.

- Hunting Prehistory on Panama’s Unknown North Coast – Documents the 1952 excavations of sites in Northern Panama.

- Aboriginal Darien : Past and Present – Documents the flora, fauna and ethnography of parts of Panama through a journey in 1954.

- On the Trail of Prehistoric America – Documents an Ecuador expedition in 1957, along with brief ethnographic footage of the Colorado Indians.

- Mexico in Fiesta Masks

- Uncovering an Ancient Mexican Temple

- Exploring Panama’s Prehistoric Past

- Uncovering Mexico’s Forgotten Treasures

Bibliography

[edit]- America's First Settlers, the Indians National Geographic, 1937

- Great Stone Faces of the Mexican Jungle National Geographic, 1940

- An Initial Series from Tres Zapotes Mexican Archaeology Series, National Geographic, 1942

- Origin myth of Acoma and other records BAE Bulletin 135, 1942

- Finding Jewels of Jade in a Mexican Swamp (with Marion Stirling) National Geographic, 1942

- La Venta’s Green Stone Tigers National Geographic, 1943

- Stone Monuments of Southern Mexico BAE Bulletin 138, 1943

- Indians of the Southeastern United States National Geographic, 1946

- On the Trail of La Venta Man National Geographic, 1947

- Haunting Heart of the Everglades/Indians of the Far West (with A. H. Brown) National Geographic, 1948

- Stone Monuments of the Río Chiquito BAE Bulletin 157, 1955

- Indians of the Americas National Geographic Society, 1955

- The use of the atlatl on Lake Patzcuaro, Michoacan BAE Bulletin 173, 1960

- Electronics and Archaeology (with F. Rainey and M. W. Stirling Jr) Expedition Magazine, 1960

- Monumental Sculpture of Southern Veracruz and Tabasco Handbook of Middle American Indians, 1965

- Early History of the Olmec Problem Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec, 1967

- Solving the mystery of Mexico's Great Stone Spheres National Geographic, 1969

- Historical and ethnographical material on the Jivaro Indians BAE Bulletin 117

- An archeological reconnaissance in Southeastern Mexico BAE Bulletin 164

- Tarquí, an early site in Manabí Province, Ecuador (with Marion Stirling) BAE Bulletin 186

- Archaeological notes on Almirante Bay, Panama (with Marion Stirling) BAE Bulletin 191

- Archaeology of Taboga, Urabá, and Taboguilla Islands, Panama (with Marion Stirling) BAE Bulletin 191

- El Limón, an early tomb site in Coclé Province Panama (with Marion Stirling) BAE Bulletin 191

Notes

[edit]- ^ Date information sourced from Library of Congress Authorities data, via corresponding WorldCat Identities linked authority file (LAF). Retrieved on 2008-05-15.

- ^ a b c d "Matthew Williams Stirling and Marion Stirling Pugh papers". Smithsonian Institution.

The Matthew Williams Stirling and Marion Stirling Pugh papers, 1876-2004 (bulk 1921-1975), document the professional and personal lives of Matthew Stirling, Smithsonian archaeologist and Chief of the Bureau of American Ethnology (1928-1957), and his wife and constant collaborator, Marion Stirling Pugh.

- ^ a b c d e Conroy, Sarah Booth (July 8, 1996). "ARCHAEOLOGIST MARION PUGH, DIGGING UP MEMORIES". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "Marion Stirling Pugh, 89". The Washington Post. May 11, 2001. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Stirling, M.W., 1969, An Occurrence of Great Stone Spheres in Jalisco State, Mexico. National Geographic Research Reports. v. 7, pp. 283–286.

- ^ Stuart, George. "Boundary End Archaeology Research Center". Retrieved 2006-08-29.