Margaret A. Wilcox

Margaret A. Wilcox | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1838 Chicago, Illinois, US |

| Died | March 30, 1912 Los Angeles, California, US |

| Occupation(s) | Inventor, mechanical engineer |

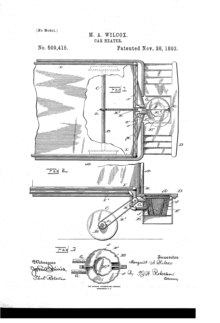

| Known for | The invention of the car heater, 1893. |

Margaret A. Wilcox (1838 – March 30, 1912) was an American mechanical engineer and inventor known for her late-nineteenth-century discoveries. The automotive heating system established the foundation for modern vehicle temperature control. She also contributed to the development of home appliance technology.

Early life

[edit]Margaret Wilcox was born in 1838 in Chicago, Illinois. Little is known about her early life,[citation needed] which was common for many women of her era, whose personal histories were often overshadowed by their male counterparts.[1] Wilcox showed an early interest in mechanical engineering despite the social conventions of her era, which often restricted women's roles to domestic domains.[citation needed]

Career and inventions

[edit]Wilcox invented the car heater.[2] She also patented a combination of a clothes washer and dishwasher machines. This invention at the time were filed under her husband's name, as it was illegal for women to file patents under their own name at the time.[1] By the time she came around to patent the car heater, it was now legal for women to file patents, and she was able to get full credit for her invention.[3]

By using the heat produced by cars' internal combustion engines, this device directed warm air into the passenger compartment. Later in time, her invention was used for the modern automobile, but originally, she designed the system for cold rail cars in Chicago.[3] Although her invention, which was patented in 1893, was innovative in that it made use of the engine's residual heat, it was originally designed without a temperature control system, which resulted in overheating.[4] As the rail car advanced and used the engine, the cabin would become hotter and hotter. Although her invention was originally made for rail cars, the application for automobiles was very successful. Cars when first introduced were open aired. When cars began to be enclosed their heating systems weren't very noticeable. It wasn't until Ford implemented Wilcox's idea in 1929 that car cabins reached a noticeable warm temperature in the car.[3] She also developed several stoves and housing appliances, including a combined cooking and hot-water-heating stove designed to save fuel by efficiently utilizing the wasted heat of the stove.[5] These inventions, although not commercially successful, demonstrated her innovative approach to solving everyday problems and her forward-thinking in appliance design.[original research?]

Legacy and modern impact

[edit]Wilcox's car heating technology was the forerunner of modern in-vehicle climate control systems, which are now ubiquitous in cars, trucks, trains, and airplanes.[6] Over the years, she made various improvements to her original design, including temperature regulation elements in the ensuing decades. Her efforts are now seen as crucial to the development of vehicle comfort, improving not only passenger convenience but also the worldwide supply chain by being essential in the transfer of commodities that are sensitive to temperature.[citation needed]

Honors

[edit]In 2020, Inventor's Digest named Wilcox's patent for the car heater one of their top ten patents by women.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Women of Interest---Margaret Wilcox". The Voice. 2021-04-30. Retrieved 2023-12-06.

- ^ McGaw, Judith A. (1997). "Inventors and Other Great Women: Toward a Feminist History of Technological Luminaries". Technology and Culture. 38 (1): 214–231. doi:10.2307/3106789. ISSN 0040-165X. JSTOR 3106789. S2CID 112618007.

- ^ a b c "Meet Margaret Wilcox, The Woman Who Invented The Car Heater". Jalopnik. 2021-04-10. Retrieved 2024-08-13.

- ^ Williamson, Lori (January 2001). "Inventing the 19th Century: 100 Inventions that Shaped the Victorian Age, from Aspirin to the Zeppelin". History: Reviews of New Books. 30 (1): 17. doi:10.1080/03612759.2001.10525935. ISSN 0361-2759. S2CID 142757304.

- ^ Stanley, Autumn (1993). Mothers and Daughters of Invention: Notes for a Revised History of Technology. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press (published October 1, 1995). p. 55. ISBN 9780813521978.

- ^ Pilato, Denise E. (2016-12-01). "Illumination or Illusion: Women Inventors at the 1893 World's Columbian Fair". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 109 (4): 374–399. doi:10.5406/jillistathistsoc.109.4.0374. ISSN 1522-1067.

- ^ "Patents by Women: Our Top 10 List". Inventors' Digest. Vol. 36, no. 9. September 2020. p. 35.