Mao Zedong's cult of personality

Mao Zedong's cult of personality was a prominent part of Chairman Mao Zedong's rule over the People's Republic of China from the state's founding in 1949 until his death in 1976. Mass media, propaganda and a series of other techniques were used by the state to elevate Mao Zedong's status to that of an infallible heroic leader, who could stand up against the West, and guide China to become a beacon of communism.[citation needed]

Mao Zedong himself recognized the need for personality cult, blaming the fall of Khrushchev on the lack of such a cult.[1][2][3][4] During the period of Cultural Revolution, Mao's personality cult soared to an unprecedented height, and he took advantage of it to mobilize the masses and attack his political opponents such as Liu Shaoqi, then Chairman of the People's Republic of China.[2][5][6] Mao's face was firmly established on the front page of People's Daily, where a column of his quotes was also printed every day; Mao's selected works were later printed in even greater circulation; the number of Mao's portraits produced (1.2 billion) exceeded the population of China at the time, in addition to a total of 4.8 billion Chairman Mao badges that were manufactured.[7] Every Chinese citizen was presented with the Little Red Book—a selection of quotes from Mao, which was required to be carried everywhere and be displayed at all public events, and citizens were expected to read the quotes from the book daily.[8] However, in the 1970s, Mao also criticized others for overdoing his own personality cult.[1][9]

After the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping and others launched the "Boluan Fanzheng" program which invalidated the Cultural Revolution and abandoned (and forbade) the use of a personality cult.[10][11][12]

History

[edit]Origin and development

[edit]

The personality cult of Mao Zedong can be traced back to the 1930s, to his involvement in Jiangxi on the Long March (1934–36), and especially during the Yan'an period in the early 1940s. In 1943, during the Yan'an Rectification Movement, newspapers began to appear with a portrait of Mao in the editorial, and soon the "ideas of Mao Zedong" became the official program of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).[13][14]

After the victory of the CCP in the Civil War, posters, portraits, and later statues of Mao began to appear in city squares, in offices and even in citizens' apartments. In 1957, Mao launched the Anti-Rightist Campaign, which was regarded as a continuation of the Yan'an Rectification Movement and further consolidated the rule of the Communist Party and Mao in mainland China.[15][16] However, the Great Leap Forward caused tens of millions of deaths during the Great Chinese Famine, forcing Mao to take a semi-retired role in 1962.[17][18] The reputation of Liu Shaoqi, the 2nd President of China, grew so high that challenged the status of Mao.[18][19] As response, Mao launched the Socialist Education Movement in 1963.

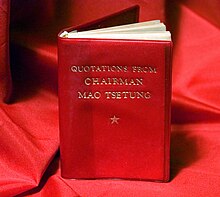

In 1964, Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, commonly known as the Little Red Book, was published for the first time, which later became one of the most famous symbols of the Cultural Revolution.

Influence of Lin Biao

[edit]The cult of Mao was brought to its peak by Lin Biao in the mid-1960s. Immediately following the May 16 Notification, Lin Biao gave a speech in which he expressed his view that the May 16 Notification was intended to "forestall a counterrevolutionary plot" and to establish the absolute authority of "Mao's thought."[20]

In a July 1966 letter to Jiang Qing circulated publicly only after Lin's death, Mao described Lin's speech as containing "deeply disturbing" ideas.[21] Mao wrote, "I have never thought that the pamphlets I have written had such magic power. Now that he has taken to inflating them, the whole country will follow suit. It seems exactly like the scene of the marrow-monger wife Wang who boasts of the quality of her goods."[21] "They flatter me by praising me to the stars, [but] things turn to their contrary: the higher one is driven, the harder his fall. I am prepared to fall, shattering all my flesh and bones. It does not matter; matter is not destroyed, it only falls to pieces."[21] Mao had agreed to the CCP Central Committee circulating Lin's speech as an official document and commented in his July 1966 letter, "This is the first time in my life that, on an important point, I have given way to another against my better judgment; let us say independently of my will."[21] Mao wrote that he could not publicly refute Lin's comments, because doing so would put a damper on "the left, all of whom speak like that."[22]

In 1970, Lin advocated for China's constitution to be amended to describe Mao as a "genius."[23] Mao rejected the planned amendment.[23]

Cultural Revolution

[edit]

Mao's cult was significantly elevated during the Cultural Revolution, despite the major failures of his Great Leap Forward campaign only years prior. The established Cultural Revolution Committee preferred not to take harsh measures against critics of the regime at first. And so Mao decided to turn to the grassroots of the revolution and "true socialism" where he reaffirmed the foundation of his cause - "in addition to left-wing radicals - Chen Boda, Jiang Qing and Lin Biao, Mao Zedong's ally in this enterprise was to be primarily Chinese youth".[24]

Mao once again proved his "fighting efficiency" after swimming across the Yangtze River in July 1966, in an annual swim that commemorates his first historic swim across in 1956. Following this upon his return to Beijing he made a powerful attack on the liberal wing of the party, mainly on President Liu Shaoqi. A little later, the CCP Central Committee approved Mao's Sixteen Points on the Cultural Revolution,[25] an early expression of the political views and objectives of the cultural revolution. It began with attacks on the leadership of Beijing University lecturer Nie Yuanzi. Following this, students of secondary schools, in an effort to confront conservative and often corrupt teachers and professors. This political initiative was strategically cultivated by Mao, who skillfully fanned the "leftists" in organizing themselves in "Red Guards". The left-controlled press subsequently launched a campaign against the liberal intelligentsia. Unable to withstand persecution, some of its representatives as well as party leaders committed suicide.

On 5 August, Mao Zedong published his own dazibao (big-character poster), a short but pivotal document titled "Bombard the Headquarters", which called out leading figures who were purportedly trying to suppress the Cultural Revolution.[26]

With the logistical support of the People's Army provided by Lin Biao, the Red Guard movement became a nationwide phenomenon. This movement persecuted leading workers and professors throughout the country, subjected them to all kinds of humiliation, and often beat them.[citation needed] Following this, at a million-strong rally in August 1966, Mao expressed full support and approval for the actions of the Red Guards, giving them further validation and permission to continue their actions. Soon after, more and more brutal atrocities by the Red Guard took place. For example, among other representatives of the intelligentsia, famous Chinese writer Lao She was brutally tortured and committed suicide.

The 10th CCP Congress, which took place in Beijing from 1 to 24 April 1969, approved the first results of the "Cultural Revolution". In this report, one of the closest associates of Mao Zedong, Marshal Lin Biao, ensured praise is focused on the "great helmsman", whose ideas were called "the highest stage in the development of Marxism–Leninism". This new CCP charter officially consolidated "the ideas of Mao Zedong" as the ideological basis of the CCP. The program part of the charter included an unprecedented provision that Lin Biao is "the continuation of the work of Comrade Mao Zedong". The entire leadership of the party, government and army was concentrated in the hands of the Chairman of the CCP, his deputy and the Standing Committee of the Politburo of the Central Committee.[27]

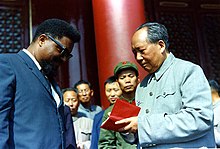

During the Cultural Revolution, Mao's personality cult manifested itself in the ubiquitous wearing of badges depicting Chairman Mao, and people carrying around a Little Red Book with the writings of Mao, which would be studied and quoted from at every opportunity. There was even a "loyalty dance" (忠字舞) which people would perform in order to demonstrate their loyalty to the great leader.

In propaganda writings, such as PLA's legendary communist soldier Lei Feng's Diary, loud slogans and fiery speeches significantly elevated the cult of Mao.

The following quote epitomizes the Red Guards' thoughts surrounding Chairman Mao, in their manifesto they wrote:

"We are the red guards of Chairman Mao, we make the country writhe in convulsions. We tear and destroy calendars, precious vases, records from the USA and England, amulets, ancient drawings and elevate above all this the portrait of Chairman Mao."

Academic Dongping Han writes that during the Cultural Revolution, rural villagers used the personality cult surrounding Mao Zedong as a political instrument to pursue their goals.[28] Ordinary villagers used Mao's words as a de facto constitution which they could effectively use in political discourses.[28]

Mao's reaction

[edit]In January 1965, before the Cultural Revolution, Mao Zedong expressed the need for personality cult in an interview with American journalist Edgar Snow, blaming the fall of the Soviet Union's Khrushchev on the lack of such a cult.[1][29] Again in December 1970, Mao told Edgar Snow in another interview that "we all need some personality cult", admitting that the personality cult around him during the Cultural Revolution was necessary to oppose Liu Shaoqi (then President of China).[2] In the first few years of the Cultural Revolution, Mao took advantage of his personality cult to mobilize the populace, especially the Red Guards, to achieve his goals, including destroying the "Four Olds" and attacking his political opponents such as Liu Shaoqi.[2][5][6]

However, during the later stage of the Cultural Revolution, Mao also criticized others for overdoing his own personality cult.[1][9] With the permission from Mao, some members of the Cultural Revolution Group such as Kang Sheng and Zhang Chunqiao publicly accused that some people promoted Mao cult only to accumulate their own "political capital" or political leverage; these people were also labelled as anti-Marxists and anti-Leninsts, and as Liu Shaoqi's loyalists.[30] Mao and the Central Committee of CCP wanted to completely control the interpretation and use of the Mao cult.[30] On the other hand, academic Alessandro Russo writes that Mao did not believe his thinking had any absolute authority.[31] Russo thinks that Mao's study initiatives in the last few years of his life were an effort to prompt mass intellectual engagement to rethink the problems raised by the Cultural Revolution.[31]

- When Lin Biao gave a speech citing the "absolute authority" of Mao's political thinking shortly after the May 16 Notification, Mao wrote privately that Lin's speech contained "deeply disturbing ideas," sarcastically comparing it to "Wife Wang boasting pumpkins to sell at the market."[32] Mao allowed the speech to be published, describing it privately as "the first time in my life that, on an important point, I have given way to another against my better judgment."[21]

- At a 1970 Party meeting where Chen Boda proclaimed the "genius" of Mao's thinking, Mao criticized Chen for making a major political error.[31] Mao likewise rebuffed Lin's effort to cite Mao's "genius" in China's constitution.[23] Mao also objected to Lin's characterization of Mao as being above the party and the state.[23]

In September 1971, Lin Biao died in a plane crash after a "failed coup" against Mao, known as the "Lin Biao incident".[33][34] Chen Boda lost power and became imprisoned in 1970 due to his support of Lin Biao.[35][36]

Characteristics

[edit]Propaganda

[edit]

During the Chinese Cultural Revolution artists were condemned as counter revolutionaries, and their work was destroyed. Instead this was replaced with government made art that supported Maoism,[37] and redirected efforts towards agriculture, industry and national defense, as well as concerns such as hygiene and family planning.[38] Under the command of Lin Biao, the People's Liberation Army's efforts were increasingly employed to bolster the personality cult surrounding Mao, eventually creating Mao's god-like image.[39] In addition to this revolutionary songs such as Mao Zedong is our sun or Hymn to Chairman Mao were sung by schoolchildren, soldiers, prisoners and office workers. These tunes were also played from loudspeakers installed on street corners, railway stations, dormitories, canteens and all major institutions.[40]

Artwork

[edit]Images of Mao's face appeared everywhere, from portraits in schools and government buildings, to street signs and wall murals, even small shrines within private homes were not unusual.[41][40] Guided by Maoist thought, the contents of the propaganda were militant, with messages of proletarian ideology, communist morale and spirit, and revolutionary heroism. Simplistic in design and coloring,[42] red was heavily featured and symbolized everything revolutionary, good and moral.[43] Depictions of Mao often featured him as a benevolent father, bringing the Confucian mechanisms of obedience into play.[43] Mao was frequently portrayed either leading or directing the masses, or looming over them like a demigod. His image was considered more important than the occasion for which a particular work of propaganda art was designed: in a number of cases, identical posters dedicated to Mao were published in different years bearing different slogans.[43]

Film in China widely reproduced Mao's image and voice, and served to gather the masses to celebrate Mao.[44]: 52

The Great Four titles

[edit]Emphasizing his ability to steer China's future, Mao was referred to as "the great leader Chairman Mao" (伟大领袖毛主席) in public and he was entitled "the great leader, the great supreme commander, the great teacher and the great helmsman" (伟大的领袖、伟大的统帅、伟大的导师、伟大的舵手) during the Cultural Revolution. This could also be influenced by the role Mao played in guiding the Red Army on the Long March to escape the Chinese Nationalist Party. The accounts by Mao and his followers during this time painted him as innovative, inspirational and strategically brilliant, an assessment at odds with the views of several historians.[41]

Little Red Book

[edit]

Officially titled 'Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung', it was central symbol of the Cultural Revolution. The book was used to promote the popularity of Chairman Mao, and his brand of communism called Maoism'. Wrapped in a distinctive red vinyl cover, it became more commonly known as the 'Little Red Book' . This book contained a series of political and cultural statements from Mao Zedong's speeches and writings, which campaigned the slogan from the Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto, "Workers of the world, unite!".

Printed since 1964 until around Mao's death in 1976, over a billion copies were distributed throughout China.[45] During the Cultural Revolution it became almost mandatory for all citizens to carry a copy, so that they could easily refer to it for guidance and become inspired. Failure to produce a copy when requested would often result in a punishment from the Red Guard, which varied from verbal harassment and beatings, to a prison sentence.[41] The final edition listed 267 quotations spanning over 25 topics such as war, peace, unity & discipline.[46] The simplification of Mao's writings also finally gave access to the thoughts and ideas of communists to peasants and lower-class citizens, this helped to further solidify support for his cult of personality.

Notable Quotes from the Little Red Book

[edit]"Every Communist must grasp the truth: Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun."

This phrase was first used during an emergency meeting of the CCP on 7 August 1927, at the beginning of the Chinese Civil War.[47]

"All reactionaries are paper tigers. In appearance, the reactionaries are terrifying, but in reality they are not so powerful."

A "Paper Tiger" refers to something or someone that claims or appears to be powerful and/or threatening, but actually has no real power. It was popularized by Mao Zedong, often using it against political opponents such as the U.S. Government.

"A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery... A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another."

This quote from Mao emphasizes the struggle and difficulty of the communist revolution and the means by which he is willing to achieve it, suggesting that violence will be an unavoidable component of the revolution. Mao coined the phrase in his 1927 Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan, in which Mao had described his theory that the peasantry would be the revolutionary class in China.[48]

Loyalty dance

[edit]In the late 60s, during the Cultural Revolution, Mao's cult of personality reached new heights, with citizens performing a "Loyalty Dance" (忠字舞; zhōngzì wǔ) to express their love to the chairman.[49] This simple dance did not involve much more than stretching one's arms from the heart to Mao's portrait, with movements originating from a folk dance popular in Xinjiang. It was frequently accompanied by revolutionary songs including "Beloved Chairman Mao", "Golden Hill of Beijing" or "Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman". Some lyrics included the quote "No matter how close our parents are to us, they are not as close as our relationship with Mao", which was used to inspire a spirit of collective worship.[50] A notable slogan related to the Loyalty Dance was the "Three Loyalties" (三忠于): loyalty to Chairman Mao; loyalty to Mao Zedong Thought; loyalty to Chairman Mao's revolutionary line.[51] The loyalty dance (忠字舞; zhōngzì wǔ) was an everyday fixture of life in the late 1960s, which was practiced in order to display one's lifelong devotion to Mao Zedong and exercise total discipline.[52] Nevertheless, by the 70's it was fleeting, and as the cultural revolution came to an end it rapidly waned.[50]

Mango worship

[edit]In August 1968 Mao presented members of a 30,000-strong propaganda team, who had been sent to pacify a Red Guard insurrection at Tsinghua University, with four dozen mangos as a sign of appreciation. Mao had given his security chief Wang Dongxing the fruits for delivery to leaders of the propaganda team.[53] Mao had been given the mangos from a delegation from Pakistan, headed by foreign minister Mian Arshad Hussain, and sent them to a range of student groups in the capital. "The factories and universities that received the mangoes were overfilled with joy at this Great, Greatest, Happiest of Events." Part of the Mao cult was about preserving and showing the mangos: some were placed in glass, others were put in a jar of formaldehyde. In one case, water in a tank in which one of the mangos was being kept was given to factory workers, so they could "literally [be] filled with the spirit of Mao."[54]

After Mao's death

[edit]

Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee Ye Jianying in 1979 described the time of Mao Zedong's reign as a "feudal fascist dictatorship". A different assessment was later given.[55]

"Comrade Mao Zedong is a great Marxist, a great proletarian revolutionary, strategist and theorist. If we consider his life and work as a whole, his merits before the Chinese revolution to a large extent prevail over misses, despite the serious mistakes made by him in the "cultural revolution". His merits occupy the main place, and mistakes take a secondary place."

— CCP leaders, 1981

Legacy

[edit]

Elements of his cult of personality continue to exist. He is still the "galleon figure" of Chinese communism, he is still honored, Mao's monuments are still standing in the cities, and his image adorns Chinese banknotes, badges and stickers. Moreover - some of Mao's monuments were erected after his death. However, the current cult of Mao among ordinary citizens, especially young people, should rather be attributed to the manifestations of modern pop culture, and not to a conscious worship of this person's thinking and deeds. In fact, Mao Zedong has become a commercial brand in modern China.[55]

Mao left his successors a country in a deep, comprehensive crisis. After the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, China's economy stagnated, intellectual and cultural life was crushed by left-wing radicals, political culture was completely absent[56][57] due to excessive public politicization and ideological chaos. The crippled fate of tens of millions of people throughout China who have suffered from senseless and brutal campaigns should be considered a particularly serious legacy of the Mao regime. Estimates of the number of victims of the Maoist regime vary greatly.[58] According to various sources, half a million[59] up to 20 million died during the cultural revolution. Another 100 million were affected one way or another in its course. The number of victims of the "Great Leap Forward" was even greater, but since the majority of them were in the rural population, even the approximate number characterizing the scale of the disaster is unknown.[citation needed]

The ideology of Maoism has also had a great influence on the development of leftists, including revolutionary movements in many countries of the world — the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, the Shining Path in Peru, the "Maoist Centre" in Nepal, and the communist movements in the US and Europe.[60] Meanwhile, China itself, after the death of Mao, in its economy has moved far from the ideas of Mao Zedong, preserving the communist ideology. The reforms initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1979 and continued by his followers de facto made the Chinese economy capitalistic, with corresponding consequences for domestic and foreign policy.[61]

In China itself, the persona of Mao is evaluated extremely ambiguously. On the one hand, part of the population sees him as a hero of the Civil War, a strong ruler, a charismatic personality.[62] Some older Chinese people are nostalgic for their confidence in the future, equality and the absence of corruption, which, in their opinion, existed in the era of Mao.[63] On the other hand, many people cannot forgive Mao for the cruelty and mistakes of his massive campaigns, especially the cultural revolution. Today in China, it is allowed to speak openly about the role of Mao in the modern history of the country, discussions about the negative aspects of his rule are allowed,[64] however, too harsh criticism is not welcomed and suppressed. In the PRC, the official formula for evaluating his activity remains the opinion given by Mao himself as a characteristic of Stalin's activity (as a response to the revelations in Khrushchev's secret report): 70 percent of victories and 30 percent of mistakes.[65][66] In this way, the CCP is seeking recognition of its power in a situation where the bourgeois economy in the PRC is combined with communist ideology.[61]

Mao has been depicted on postage stamps in China, Albania,[67] and East Germany.[68] The collage "Marilyn in the image of Mao"[69] or "Marilyn/Mao" (created by the American photographer Philippe Halsman in 1952) turned into an artistic image used by many famous artists such as Salvador Dalí, Chinese artists Yu Juhan, and Hua Jimin.[70]

In 1982, Article 10 was added to the Constitution of the Chinese Communist Party, forbidding "all forms of personality cult."[71]: 29

Chairman Mao badge

[edit]Trading markets of Chairman Mao badges were common during the Cultural Revolution, particularly during the chuanlian movement in which Red Guards travelled for free around the country to "exchange revolutionary experiences". Maoist memorabilia began reemerging in the early 1990s, as teenagers who were too young to remember the era of the Cultural Revolution began to snap up Mao badges for their kitsch appeal.[72] Moreover, in the 1990s, the markets were targeting Westerners with commodification. Cultural Revolution badges are rampant in markets frequented by Chinese and Westerners, and new replicas of badges are sold in luxury hotels and tourist sites only minutes from Mao's mausoleum. "Mao badge museums" can be toured at modest prices and an American catalogue advertised Mao badges for $12 a badge.[73]

Badges were most common from 1967 to 1969, when wearing them was considered a sign of loyalty to the Great Helmsman. There were many such badges. Icons with a portrait of Mao became a symbol of his cult of personality. An estimated 2 billion badges have been manufactured during the years of the cultural revolution. In 1969, Mao said that the country needed aluminum to produce aircraft, and they began to make less icons.[74]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Keith, Ronald C. (2004). "Review: History, Contradiction, and the Apotheosis of Mao Zedong". China Review International. 11 (1): 1–8. ISSN 1069-5834. JSTOR 23732901. Archived from the original on 4 March 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

In a January 9, 1965, interview with Edgar Snow, Mao claimed that Khrushchev fell "because he had no cult at all." ...... In the early 1970s he blamed others for overdoing his own personality cult, attacking his heir apparent Lin Biao and the senior Party theoretician Chen Boda.

- ^ a b c d "Record of Conversation from [Chairman Mao Zedong's] Meeting with [Edgar] Snow (December 18, 1970)". Wilson Center. Archived from the original on 4 March 2023.

Mao: We all adore someone. Would you be glad if nobody adored you? Would you be glad if nobody read your books and articles? We all need some personality cult, even you [need it]...... It was for the purpose of opposing Liu Shaoqi.

- ^ Wu, Zhifei (14 November 2013). "毛泽东对"个人崇拜"的态度演变" [Mao Zedong's attitude towards "personality cult"]. People's Net (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (1 June 2005). "China must confront dark past, says Mao confidant". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ a b Leese, Daniel (2017), Naimark, Norman; Pons, Silvio; Quinn-Judge, Sophie (eds.), "Mao Zedong as a Historical Personality", The Cambridge History of Communism: Volume 2: The Socialist Camp and World Power 1941–1960s, The Cambridge History of Communism, vol. 2, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 269–290, ISBN 978-1-107-59001-4, archived from the original on 6 March 2020, retrieved 4 March 2023

- ^ a b Leese, Daniel (1 September 2007). "The Mao Cult as Communicative Space". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 8 (3–4): 623–639. doi:10.1080/14690760701571247. ISSN 1469-0764. S2CID 143840866.

- ^ Barmé, Geremie. (1996). Shades of Mao : the posthumous cult of the great leader. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-585-26901-7. OCLC 45729144.

- ^ Chang, Jung, 1952- (2007). Mao : the unknown story. Halliday, Jon. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-950737-6. OCLC 71346736.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lin, Xu and Wu 1995. p. 48.

- ^ Teon, Aris (1 March 2018). "Deng Xiaoping On Personality Cult And One-Man Rule – 1980 Interview". The Greater China Journal. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Huang, Zheping (26 February 2018). "Xi Jinping could now rule China for life—just what Deng Xiaoping tried to prevent". Quartz. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ "第八章: 十一届三中全会开辟社会主义事业发展新时期". cpc.people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 1 March 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Selden, Mark (1995). "Yan'an Communism Reconsidered". Modern China. 21 (1): 8–44. doi:10.1177/009770049502100102. ISSN 0097-7004. JSTOR 189281. S2CID 145316369.

- ^ Judd, Ellen R. (1985). "Prelude to the "Yan' an Talks": Problems in Transforming a Literary Intelligentsia". Modern China. 11 (3): 377–408. doi:10.1177/009770048501100304. ISSN 0097-7004. JSTOR 188808. S2CID 144585942.

- ^ King, Gilbert. "The Silence that Preceded China's Great Leap into Famine". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Mu, Guangren. "反右运动的六个断面". Yanhuang Chunqiu. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Roderick (1999). The Origins of the Cultural Revolution: Volume III, the Coming of the Cataclysm 1961--1966. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11083-9. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Three Chinese Leaders: Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Deng Xiaoping | Asia for Educators | Columbia University". afe.easia.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Gao, Hua. "从《七律·有所思》看毛泽东发动文革的运思". Chinese University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- ^ a b c d e Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- ^ Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- ^ a b c d Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the twentieth-century world : a concise history. Durham [NC]: Duke University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4. OCLC 503828045.

- ^ Хомич, Л. Н. (29 May 2009). "Работа редактора над переизданием произведений классиков литературы, в частности устранение искажений авторского текста (на примере произведений В. С. Короткевича)". Технологія і техніка друкарства (1-2(23-24)): 142–145. doi:10.20535/2077-7264.1-2(23-24).2009.58499 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 2414-9977.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Mao Zedong: '16 Points on the Cultural Revolution' (1966)". Chinese Revolution. 5 June 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "К 60-ЛЕТИЮ ЖУРНАЛА "НОВАЯ И НОВЕЙШАЯ ИСТОРИЯ", "Новая и новейшая история"". Новая и новейшая история (3): 169–188. 2018. doi:10.7868/s0130386418030113. ISSN 0130-3864.

- ^ "Завьялова Н.А. Агональность в культуре Китая: от древности до наших дней". Человек и культура. 3 (3): 16–23. March 2018. doi:10.25136/2409-8744.2018.3.26374. ISSN 2409-8744.

- ^ a b Han, Dongping (2008). The unknown cultural revolution : life and change in a Chinese village. New York. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-58367-180-1. OCLC 227930948.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Snow, Edgar (9 January 1965). "South Of The Mountains To North Of The Seas". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

'In the Soviet Union,' I said, 'China has been criticized for fostering a "cult of personality". Is there a basis for that?' Mao thought that perhaps there was some. It was said that Stalin had been the centre of a cult of personality, and that Khrushchev had none at all. The Chinese people, critics said, had some feelings or practices of this kind. There might be some reasons for saying that. Probably Mr. Khrushchev fell because he had had no cult of personality at all...

- ^ a b Huo, Xuanji. "毛泽东崇拜现象的透视" [A Review of Mao Cult Rhetoric and Ritual in China's Cultural Revolution] (PDF). Twenty-First Century (in Chinese) (145). Chinese University of Hong Kong: 137. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- ^ Russo, Alessandro (2020). Cultural Revolution and revolutionary culture. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 129–130, 240. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4. OCLC 1156439609.

- ^ Jin, Qiu (1999). The Culture of Power: The Lin Biao Incident in the Cultural Revolution. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3529-2. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022.

- ^ "The Lin Biao Incident And The People's Liberation Army Of Purges". Hoover Institution. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ Pace, Eric (30 September 1989). "Chen Boda, 85, Leader of Chinese Purges in 60's". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "China's Continuous Revolution". University of California. Archived from the original on 4 March 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "Seeing red: The propaganda art of China's Cultural Revolution". BBC Arts. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Arbuckle, Alex (July 2016). "Cultural Revolution propaganda posters encouraged patriotism and hygiene". Mashable. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ "Mao Zedong - Personality Cult". www.globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Book extract: how Mao built up his cult of personality". South China Morning Post. 13 October 2019. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "The cult of Mao". Chinese Revolution. 23 May 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ "Cultural Revolution Campaigns (1966-1976)". chineseposters.net. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Mao Cult". chineseposters.net. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Li, Jie (2023). Cinematic Guerillas: Propaganda, Projectionists, and Audiences in Socialist China. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231206273.

- ^ "Little Red Book | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ "What is the Little Red Book?". 26 November 2015. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ "Quotes - Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun". www.shmoop.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "文革發動50週年:從十件物品來看文革". BBC News 中文 (in Traditional Chinese). 9 May 2016. Archived from the original on 31 October 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ Walder, Andrew G. (6 April 2015). China Under Mao: A Revolution Derailed. Harvard University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-674-28670-2. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b Nguyen-Okwu, Leslie (12 December 2016). "Hitler Had a Salute, Mao Had a Dance". OZY. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Gang, Qian (9 April 2020). "The Delicate Dance of Loyalty". Modern Chinese Literature and Culture Resource Center. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021.

- ^ Nguyen-Okwu, Leslie (12 December 2016). "Hitler Had a Salute, Mao Had a Dance". OZY. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ Leese, Daniel, Mao Cult, Cambridge University Press, p. 220, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511984754.008, ISBN 978-0-511-98475-4

- ^ "Chairman Mao's Mangoes". chineseposters.net. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ a b Захарьев, Ярослав Олегович (31 March 2018). "КНР и Норвегия: архитектура отношений в начале ХХI века". Journal of International Economic Affairs. 8 (1): 73–80. doi:10.18334/eo.8.1.38602. ISSN 2587-8921.

- ^ Lu, Xing, 1956- (2004). Rhetoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution : the impact on Chinese thought, culture, and communication. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-543-1. OCLC 54374711.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Andreas, Joel (10 March 2009). Rise of the Red Engineers: The Cultural Revolution and the Origins of China's New Class. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6077-5. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ "Twentieth Century Atlas - Death Tolls". necrometrics.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ Meisner, Maurice (April 1999). Mao's China and After: A History of the People's Republic, Third Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-85635-3. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ "Маоизм и организации маоистов в мире. Справка". РИА Новости (in Russian). 28 May 2010. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ a b Зотов, Георгий (23 October 2013). "Дракон с серпом и молотом. Почему в Китае коммунисты до сих пор у власти". aif.ru. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ Галенович, Юрий (29 March 2019). Великий Мао. "Гений и злодейство" (in Russian). Litres. ISBN 978-5-457-09493-2. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Головнин, Василий. "Блоги / Василий Головнин: Судьба хунвэйбина". Эхо Москвы (in Russian). Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ Mao Zedong: China's Peasant Emperor (4/4), 14 January 2015, archived from the original on 6 November 2017, retrieved 5 January 2020

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas D.; Times, Special To the New York (7 February 1989). "Legacy of Mao Called 'Great Disaster'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "China moves on from Mao". 8 September 2006. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ Only Tradition (26 September 2013), Mao Ce Dun. 75 vjetori i lindjes, 1893-1968, pulla 25 qindarka dhe 1,75 lek. Albanian stamps for the 75th anniversary of the birthday of Mao Zedong. Timbres albanais pour le 75ème anniversaire de Mao Tsé Toung, 1968., archived from the original on 4 January 2017, retrieved 5 January 2020

- ^ "Марки ГДР 1951 год". stamppost.ru. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Philippe Halsman. Marilyn as Mao. 1967 | MoMA". Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Writer, DAVID BEARD Staff (June 1995). "GOODBYE DALI: U.S. CUSTOMS OFFERS SURREAL DEAL ON PORTRAIT". Sun-Sentinel.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ Marquis, Christopher; Qiao, Kunyuan (2022). Mao and Markets: The Communist Roots of Chinese Enterprise. Kunyuan Qiao. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-26883-6. OCLC 1348572572.

- ^ Moore, Malcolm (7 October 2014). "China's latest bubble: Chairman Mao memorabilia". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Schrift, Melissa; Pilkey, Keith (1 September 1996). "Revolution Remembered: Chairman Mao Badges and Chinese Nationalist Ideolgy". The Journal of Popular Culture. 30 (2): 169–197. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1996.00169.x. ISSN 1540-5931.

- ^ "Фото: 10 символов "культурной революции" в Китае". BBC News Русская служба (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Lin Ke, Xu Tao and Wu Xujun (1995). 歷史的真實: 毛澤東身邊工作人員的證言 [The True Life of Mao Zedong: Eyewitness Accounts by Mao's Staff]. Hong Kong: Liwen Chubanshe. ISBN 9789577090980.