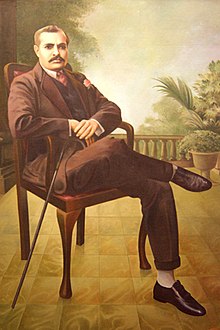

Dada Lekhraj

Lekhraj Khubchand Kirpalani (Brahma Baba) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal life | |

| Born | 15 December 1876 |

| Died | 18 January 1969 (aged 92) |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Other names | Prajapita Brahma, Brahma Baba |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Hindu spiritualist, Brahma Kumaris |

Lekhraj Khubchand Kirpalani (15 December 1876 – 18 January 1969), also known as Dada Lekhraj, was an Indian guru who was the founder of the Brahma Kumaris.

Life

[edit]Lekhraj Kirpalani was born in a Hyderabad, Sindh in 1876.[1] In his fifties, Kirpalani reported having visions and retired, returning to Hyderabad and turning to spirituality.[2]

Om Mandali

[edit]In 1936, Lekhraj established a spiritual organisation called Om Mandali. Originally a follower of the Vaishnavite Vallabhacharya sect[3] and member of the exogamous Bhaiband community,[4] he is said to have had 12 gurus[5] but started preaching or conducting his own satsangs which, by 1936, had attracted around 300 people from his community, many of them being wealthy. Once a relative reported that a spiritual being (Shiv, the supreme soul) entered in his body and spoke through him.[6] Since then, Lekhraj has been regarded by the Brahma Baba as a medium of God, and as such, speaking channeled messages of high importance within the religious movement's belief system.[7]

In 1937, Lekhraj named some of the members of his satsang as a managing committee, and transferred his fortune to the committee. This committee, known as Om Mandali, was the nucleus of the Brahma Kumaris.[2] Several women joined Om Mandali, and contributed their wealth to the association.[8]

The Sindhi community reacted unfavourably to Lekhraj's movement due to the group's philosophy that advocated women to be less submissive to their husbands, going against that strong cultural aspect at the time in India, and also preached chastity.[9][10][11]

Some organisations accused Om Mandali of being a disturber of family's personal matter. Some of the Brahma Kumaris wives were mistreated by their families, and Lekhraj was accused of sorcery and lechery.[2] He was also accused of forming a cult and controlling his community through the art of hypnotism.[12]

To avoid persecution, legal actions and opposition from family members of his followers, Lekhraj moved the group from Hyderabad to Karachi, where they settled in a highly structured ashram. The Bhaibund anti-Om Mandli Committee that had opposed the group in Hyderabad followed them.[13] On 18 January 1939, the mothers of two girls aged 12 and 13 filed an application against Om Mandali, in the Court of the Additional Magistrate in Karachi. The women, from Hyderabad, stated that their daughters were wrongfully being detained at the Om Mandali in Karachi.[9] The court ordered the girls to be sent to their mothers. Om Radhe of the Om Mandali appealed against the decision in the High Court, where the decision was upheld. Later, Hari's parents were persuaded to let their daughter stay at the Om Mandali.

Several Hindus continued their protests against Om Mandali. Some Hindu members of the Sindh Assembly threatened to resign unless the Om Mandali was finally outlawed. Finally, the Sindh Government used the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1908 to declare the Om Mandali as an unlawful association.[8] Under further pressure from the Hindu leaders in the Assembly, the Government also ordered the Om Mandali to close and vacate its premises.[14]

After the partition of India, the Brahma Kumaris moved to Mount Abu, Rajasthan in India on 5 May 1950.[15]

Lekhraj died on 18 January 1969, and the Brahma Kumaris subsequently expanded to other countries.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ 'Custodians of Purity, An Ethnography of the Brahma Kumaris', Tamasin Ramsay, PhD (2009), Monash University

- ^ a b c Abbott, Elizabeth (2001). A History of Celibacy. James Clarke & Co. pp. 172–174. ISBN 0-7188-3006-7.

- ^ The Brahma Kumaris as a 'reflexive Tradition': Responding to late modernity by Dr John Walliss, 2002, ISBN 0-7546-0951-0

- ^ The Sindh Story, by K. R. Malkani. Karachi, Allied Publishers Private Limited, 1984.

- ^ Adi Dev, by Jagdish Chander Hassija, Third Edition, Brahma Kumaris Information Services, 2003.

- ^ Walliss, John (October 1999). "From World Rejection to Ambivalence: the Development of Millenarianism in the Brahma Kumaris". Journal of Contemporary Religion. 14 (3): 375–385. doi:10.1080/13537909908580876.

- ^ Peace & Purity: the Story of the Brahma Kumaris, Liz Hodgkinson. Page 58

- ^ a b Hardy, Hardayal (1984). Struggles and Sorrows: The Personal Testimony of a Chief Justice. Vikas Publishing House. pp. 37–39. ISBN 0-7069-2563-7.

- ^ a b Hodgkinson, Liz (2002). Peace and Purity: The Story of the Brahma Kumaris a Spiritual Revolution. HCI. pp. 2–29. ISBN 1-55874-962-4.

- ^ Chryssides, George D. (2001). Historical Dictionary of New Religious Movements. Scarecrow Press. pp. 35–36.

- ^ Barrett, David V. (2001). The New Believers: A Survey of Sects, Cults and Alternative Religions. Cassell & Co. ISBN 978-0-304-35592-1.

'sex is an extreme expression of 'body-consciousness' and also leads to the other vices', probably stems in part from the origins of the movement in the social conditions of the 1930s India when women had to submit to their husbands.

- ^ Radhe, Brahma-Kumari (1939). Is this justice?: Being an account of the founding of the Om Mandli & the Om Nivas and their suppression, by application of the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1908. Pharmacy Printing Press. pp. 35–36.

- ^ Howell, Julia Day (2005). Peter Clarke (ed.). Encyclopedia of New Religious Movements. Routledge. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-415-26707-6.

The call for women brahmins (i.e. kumaris or 'daughters') to remain celibate or chaste in marriage inverted prevailing social expectations that such renunciation was proper only for men and that the disposal of women's sexuality should remain with their fathers and husbands. The 'Anti-Om Mandali Committee' formed by outraged male family members violently persecuted Brahma Baba's group, prompting their flight to Karachi and withdrawal from society. Intense world rejection gradually eased after partition in 1947, when the BKs moved from Pakistan to Mt. Abu.

- ^ Coupland, Reginald (1944). The Indian Problem: Report on the Constitutional Problem in India. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Chander, B. K. Jagdish (1981). Adi Dev: The first man. B.K. Raja Yoga Center for the Brahma Kumaris World Spiritual University.

- ^ Hunt, Stephen J. (2003). Alternative Religions: A Sociological Introduction. Ashgate. p. 120. ISBN 0-7546-3410-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Chander, B. K. Jagdish (1984). A Brief Biography of Brahma Baba. Brahma Kumaris World Spiritual University.

- Radhe, Om (1937). Is this Justice?. Pharmacy Press, ltd.