LGBTQ community

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2023) |

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

The LGBTQ community (also known as the LGBT, LGBTQ+, LGBTQIA+, or queer community) is a loosely defined grouping of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning individuals united by a common culture and social movements. These communities generally celebrate pride, diversity, individuality, and sexuality.[not verified in body] LGBTQ activists and sociologists see LGBTQ community-building as a counterweight to heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, sexualism, and conformist pressures that exist in the larger society. The term pride or sometimes gay pride expresses the LGBTQ community's identity and collective strength; pride parades provide both a prime example of the use and a demonstration of the general meaning of the term.[not verified in body] The LGBTQ community is diverse in political affiliation. Not all people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender consider themselves part of the LGBTQ community.

Groups that may be considered part of the LGBTQ community include gay villages, LGBTQ rights organizations, LGBTQ employee groups at companies, LGBTQ student groups in schools and universities, and LGBT-affirming religious groups.

LGBTQ communities may organize themselves into, or support, movements for civil rights promoting LGBTQ rights in various places around the world. At the same time, high-profile celebrities in the broader society may offer strong support to these organizations in certain locations; for example, LGBTQ advocate and entertainer Madonna stated, "I was asked to perform at many Pride events around the world — but I would never, ever turn down New York City".[4]

Terminology

LGBT, or GLBT, is an initialism that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. In use since the 1990s, the term is an adaptation of the initialism LGB, which was used to replace the term gay – when referring to the community as a whole – beginning in various forms largely in the early 1990s.[5][citation needed]

While the movement had always included all LGBT people, the one-word unifying term in the 1950s through the early 1980s was gay (see Gay liberation). Throughout the 1970s and '80s, a number of groups with lesbian members, and pro-feminist politics, preferred the more representative, lesbian and gay.[6] By the early nineties, as more groups shifted to names based on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT), queer was also increasingly reclaimed as a one-word alternative to the ever-lengthening string of initials, especially when used by radical political groups, some of which had been using "queer" since the '80s.[6]

The initialism, as well as common variants such as LGBTQ, have been adopted into the mainstream in the 1990s[7] as an umbrella term for use when labeling topics about sexuality and gender identity. For example, the LGBT Movement Advancement Project termed community centers, which have services specific to those members of the LGBT community, as "LGBT community centers" in comprehensive studies of such centers around the United States.[8]

The initialism LGBT is intended to emphasize a diversity of sexuality and gender identity-based cultures. It may refer to anyone who is non-heterosexual or non-cisgender, instead of exclusively to people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender.[9] Recognize this inclusion as a popular variant that adds the letter Q for those who identify as queer or are questioning their sexual identity; LGBTQ has been recorded since 1996.[10][11]

Disagreement between what precise wording is best is still present in 2023. Some propose adding more letters to make the participation of those groups explicit.[12] Detractors of this approach argue that adding letters implicitly excludes others or makes for worse branding.[citation needed]

Symbols

The gay community is frequently associated with certain symbols, especially the rainbow or rainbow flags. The Greek lambda symbol ("L" for liberation), triangles, ribbons, and gender symbols are also used as "gay acceptance" symbol. There are many types of flags to represent subdivisions in the gay community, but the most commonly recognized one is the rainbow flag. According to Gilbert Baker, creator of the commonly known rainbow flag, each color represents a value in the community:

- pink = sexuality

- red = life

- orange = healing

- yellow = the sun

- green = nature

- blue = art

- indigo = harmony

- violet = spirit

Later, pink and indigo were removed from the flag, resulting in the present-day flag which was first presented at the 1979 Pride Parade. Other flags include the Victory over AIDS flag, the Leather Pride flag, and the Bear Pride flag.[13]

The lambda symbol was originally adopted by Gay Activists Alliance of New York in 1970 after they broke away from the larger Gay Liberation Front. Lambda was chosen because people might confuse it for a college symbol and not recognize it as a gay community symbol unless one was actually involved in the community. "Back in December of 1974, the lambda was officially declared the international symbol for gay and lesbian rights by the International Gay Rights Congress in Edinburgh, Scotland."[13]

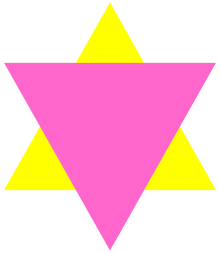

The triangle became a symbol for the gay community after the Holocaust. Not only did it represent Jews, but homosexuals who were killed because of German law. During the Holocaust, homosexuals were labeled with pink triangles to distinguish between them, Jews, regular prisoners, and political prisoners. The black triangle is similarly a symbol for females only to represent lesbian sisterhood.

The pink and yellow triangle was used to label Jewish homosexuals. Gender symbols have a much longer list of variations of homosexual or bisexual relationships which are clearly recognizable but may not be as popularly seen as the other symbols. Other symbols that relate to the gay community or gay pride include the gay-teen suicide awareness ribbon, AIDS awareness ribbon, labrys, and purple rhinoceros.[14][15]

In the fall of 1995, the Human Rights Campaign adopted a logo (yellow equal sign on deep blue square) that has become one of the most recognizable symbols of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community. The logo can be spotted the world over and has become synonymous with the fight for equal rights for LGBTQ people.[16]

One of the most notable recent changes was made in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on June 8, 2017. They added two new stripes to the rainbow flag, one black and one brown. These were intended to highlight members of color within the LGBTQ community.[17]

Human and legal rights

The LGBTQ community represented by a social component of the global community that is believed by many, including heterosexual allies, to be underrepresented in the area of civil rights. The current struggle of the gay community has been largely brought about by globalization. In the United States, World War II brought together many closeted rural men from around the nation and exposed them to more progressive attitudes in parts of Europe. Upon returning home after the war, many of these men decided to band together in cities rather than return to their small towns. Fledgling communities would soon become political in the beginning of the gay rights movement, including monumental incidents at places like Stonewall. Today, many large cities have gay and lesbian community centers. Many universities and colleges across the world have support centers for LGBTQ students. The Human Rights Campaign,[18] Lambda Legal, the Empowering Spirits Foundation,[19] and GLAAD[20] advocate for LGBTQ people on a wide range of issues in the United States. There is also an International Lesbian and Gay Association. In 1947, when the United Kingdom adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), LGBTQ activists clung to its concept of equal, inalienable rights for all people, regardless of their race, gender, or sexual orientation. The declaration does not specifically mention gay rights, but discusses equality and freedom from discrimination.[21] In 1962, Clark Polak joined The Janus Society in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[22] Only a year after, he became president. In 1968, he announced that the Society would be changing their name to Homosexual Law Reform Society; "Homosexuals are now willing to fly under their own colors" (Stewart, 1968).

Same-sex marriage

In some parts of the world, partnership rights or marriage have been extended to same-sex couples. Advocates of same-sex marriage cite a range of benefits that are denied to people who cannot marry, including immigration, health care, inheritance and property rights, and other family obligations and protections, as reasons why marriage should be extended to same-sex couples. Opponents of same-sex marriage within the gay community argue that fighting to achieve these benefits by means of extending marriage rights to same-sex couples privatizes benefits (e.g., health care) that should be made available to people regardless of their relationship status. They further argue that the same-sex marriage movement within the gay community discriminates against families that are composed of three or more intimate partners. Opposition to the same-sex marriage movement from within the gay community should not be confused with opposition from outside that community.[citation needed]

Media

The contemporary lesbian and gay community has a growing and complex place in the American and Western European media. Lesbians and gay men are often portrayed inaccurately in television, films, and other media; the gay community is often portrayed as many stereotypes, such as gay men being portrayed as flamboyant and bold. Like other minority groups, these caricatures are intended to ridicule this marginalized group.[23]

There is currently a widespread ban of references in child-related entertainment, and when references do occur, they almost invariably generate controversy. In 1997, when American comedian Ellen DeGeneres came out of the closet on her popular sitcom, many sponsors, such as the Wendy's fast food chain, pulled their advertising.[24] Also, a portion of the media has attempted to make the gay community included and publicly accepted with television shows such as Will & Grace or Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. This increased publicity reflects the Coming out movement of the LGBTQ community. As more celebrities came out, more shows developed, such as the 2004 show The L Word. These depictions of the LGBTQ community have been controversial, but beneficial for the community. The increase in visibility of LGBTQ people allowed for the LGBTQ community to unite to organize and demand change, and it has also inspired many LGBTQ people to come out.[25]

In the United States, gay people are frequently used as a symbol of social decadence by celebrity evangelists and by organizations such as Focus on the Family. Many LGBTQ organizations exist to represent and defend the gay community. For example, the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation in the United States and Stonewall in the UK work with the media to help portray fair and accurate images of the gay community.[26][27]

As companies are advertising more and more to the gay community, LGBTQ activists are using ad slogans to promote gay community views. Subaru marketed its Forester and Outback with the slogan "It's Not a Choice. It's the Way We're Built", which was later used in eight U.S. cities on streets or in gay rights events.[28]

Social media

Social media is often used as a platform for the LGBTQ community to congregate and share resources. Search engines and social networking sites provide numerous opportunities for LGBTQ people to connect with one another; additionally, they play a key role in identity creation and self-presentation.[29][30][31] Social networking sites allow for community building as well as anonymity, allowing people to engage as much or as little as they would like.[32] The variety of social media platforms, including Facebook, TikTok, Tumblr, Twitter, and YouTube, have differing associated audiences, affordances and norms.[31] These varying platforms allow for more inclusivity as members of the LGBTQ community have the agency to decide where to engage and how to self-present themselves.[31] The existence of the LGBTQ community and discourse on social media platforms is essential to disrupt the reproduction of hegemonic cis-heteronormativity and represent the wide variety of identities that exist.[32]

Before its ban on adult content in 2018, Tumblr was a platform uniquely suited for sharing trans stories and building community.[33] Mainstream social media platforms like TikTok have also been beneficial for the trans community by creating spaces for folks to share resources and transition stories, normalizing trans identity.[34] It has been found that access to LGBTQ content, peers, and community on search engines and social networking sites has allowed for identity acceptance and pride within LGBTQ community.[35]

Algorithms and evaluative criteria control what content is recommended to users on search engines and social networking site.[30] These can reproduce stigmatizing discourses that are dominant within society, and result in negatively impacting LGBTQ self-perception.[30] Social media algorithms have a significant impact on the formation of the LGBTQ community and culture.[36] Algorithmic exclusion occurs when exclusionary practices are reinforced by algorithms across technological landscapes, directly resulting in excluding marginalized identities.[34] The exclusion of these identity representations causes identity insecurity for LGBTQ people, while further perpetuating cis-heteronormative identity discourse.[34] LGBTQ users and allies have found methods of subverting algorithms that may suppress content in order to continue to build these online communities.[34]

Buying power

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2023) |

According to Witeck-Combs Communications, Inc. and Marketresearch.com, the 2006 buying power of United States gays and lesbians was approximately $660 billion and was then expected to exceed $835 billion by 2011.[37] Gay consumers can be very loyal to specific brands, wishing to support companies that support the gay community and also provide equal rights for LGBTQ workers. In the UK, this buying power is sometimes abbreviated to "the pink pound."[38]

According to an article by James Hipps, LGBTQ Americans are more likely to seek out companies that advertise to them and are willing to pay higher prices for premium products and services. This can be attributed to the median household income compared to same-sex couples to opposite-sex couples, as they are twice as likely to have graduated from college, twice as likely to have an individual income over $60,000 and twice as likely to have a household income of $250,000 or more. [39]

Consumerism

Although many claims that the LGBTQ community is more affluent when compared to heterosexual consumers, research has proven that false.[40] However, the LGBTQ community is still an important segment of consumer demographics because of the spending power and loyalty to brands that they have.[41] Witeck-Combs Communications calculated the adult LGBTQ buying power at $830 billion for 2013.[40] Same-sex partnered households spend slightly more than the average home on any given shopping trip.[42] But, they also make more shopping trips compared to the non-LGBTQ households.[42] On average, the difference in spending with same-sex partnered home is 25 percent higher than the average United States household.[42] According to the University of Maryland gay male partners earn $10,000 less on average compared to heterosexual men.[40] However, partnered lesbians receive about $7,000 more a year than heterosexual married women.[40] Hence, same-sex partners and heterosexual partners are about equal concerning consumer affluence.[40]

The LGBTQ community has been recognized for being one of the largest consumers in travel. Travel includes annual trips, and sometimes even multiple annual trips. Annually, the LGBTQ community spends around $65 billion on travel, totaling 10 percent of the United States travel market.[40] Many common travel factors play into LGBTQ travel decisions, but if there is a destination that is especially tailored to the LGBTQ community, then they are more likely to travel to those places.[40]

Demographics

In a survey conducted in 2012, younger Americans are more likely to identify as gay.[42] Statistics continue to decrease with age, as adults between ages 18–29 are three times more likely to identify as LGBTQ than seniors older than 65.[42] These statistics for the LGBTQ community are taken into account just as they are with other demographics to find trend patterns for specific products.[40] Consumers who identify as LGBTQ are more likely to regularly engage in various activities as opposed to those who identify as heterosexual.[40] According to Community Marketing, Inc., 90 percent of lesbians and 88 percent of gay men will dine out with friends regularly. And similarly, 31 percent of lesbians and 50 percent of gay men will visit a club or a bar.[40]

And at home, the likelihood of LGBTQ women having children at home as non-LGBTQ women is equal.[42] However, LGBTQ men are half as likely when compared with non-LGBTQ men to have children at home.[42] Household incomes for sixteen percent of LGBTQ Americans range above $90,000 per year, in comparison with 21 percent of the overall adult population.[42] However, a key difference is that those who identify as LGBTQ have fewer children collectively in comparison to heterosexual partners.[40] Another factor at hand is that LGBTQ populations of color continue to face income barriers along with the rest of the race issues, so they will expectedly earn less and not be as affluent as predicted.[40]

An analysis of a Gallup survey shows detailed estimates that – during the years 2012 through 2014 – the metropolitan area with the highest percentage of LGBTQ community was San Francisco, California. The next highest were Portland, Oregon, and Austin, Texas.[43]

A 2019 survey of the Two-Spirit and LGBTQ+ population in the Canadian city of Hamilton, Ontario, called Mapping the Void: Two-Spirit and LGBTQ+ Experiences in Hamilton showed that out of 906 respondents, when it came to sexual orientation, 48.9% identified as bisexual/pansexual, 21.6% identified as gay, 18.3% identified as lesbian, 4.9% identified as queer, and 6.3% identified as other (a category consisting of those who indicated they were asexual, heterosexual, or questioning, and those who gave no response for their sexual orientation).[44]

A 2019 survey of trans and non-binary people in Canada called Trans PULSE Canada showed that out of 2,873 respondents. When it came to sexual orientation, 13% identified as asexual, 28% identified as bisexual, 13% identified as gay, 15% identified as lesbian, 31% identified as pansexual, 8% identified as straight or heterosexual, 4% identified as two-spirit, and 9% identified as unsure or questioning.[45]

In a survey carried out in 2021, Gallup found that 7.1% of U.S. adults identify as "lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or something other than straight or heterosexual".[46]

Marketing

Marketing towards the LGBTQ community was not always a strategy among advertisers. For the last three to four decades, Corporate America has created a market niche for the LGBTQ community. Three distinct phases define the marketing turnover: 1) shunning in the 1980s, 2) curiosity and fear in the 1990s, and 3) pursuit in the 2000s.[47]

Just recently, marketers have picked up the LGBTQ demographic. With a spike in same-sex marriage in 2014, marketers are figuring out new ways to tie in a person's sexual orientation to a product being sold.[42] In efforts to attract members of the LGBTQ community to their products, market researchers are developing marketing methods that reach these new families.[42] Advertising history has shown that when marketing to the family, it was always the wife, the husband, and the children.[42] But today, that is not necessarily the case. There could be families of two fathers or two mothers with one child or six children. Breaking away from the traditional family setting, marketing researchers notice the need to recognize these different family configurations.[42]

One area that marketers are subject to fall under is stereotyping the LGBTQ community. When marketing towards the community, they may corner their target audience into an "alternative" lifestyle category that ultimately "others" the LGBTQ community.[42] Sensitivity is important when marketing towards the community. When marketing towards the LGBTQ community, advertisers respect the same boundaries.

Marketers also refer to LGBTQ as a single characteristic that makes an individual.[42] Other areas can be targeted along with the LGBTQ segment such as race, age, culture, and income levels.[42] Knowing the consumer gives these marketers power.[41]

Along with attempts to engage with the LGBTQ community, researchers have found gender disagreements among products with respective consumers.[47] For instance, a gay male may want a more feminine product, whereas a lesbian female may be interested in a more masculine product. This does not hold for the entire LGBTQ community, but the possibilities of these differences are far greater.[47] In the past, gender was seen as fixed, and a congruent representation of an individual's sex. It is understood now that sex and gender are fluid separately. Researchers also noted that when evaluating products, a person's biological sex is as equal is a determinant as their self-concept.[47] As a customer response, when the advertisement is directed towards them, gay men and women are more likely to have an interest in the product.[41] This is an important factor and goal for marketers because it indicates future loyalty to the product or brand.

Discrimination

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (November 2023) |

LGBTQ individuals have faced a long history of discrimination. They've been labeled as mentally ill, faced forced attempts to change who they are, and experienced hate crimes and exclusion from jobs, homes, and public places.[48]

Survey studies show that instances of personal discrimination are common among LGBTQ community. This includes things like slurring, sexual harassment, and violence.[49] According to a survey conducted for National Public Radio, at least one in five LGBTQ Americans have experienced discrimination in public because of their identity. This includes in housing, education, employment, and law enforcement. Furthermore, the report reveals that people of color in the LGBTQ community are twice more likely than white people in the LGBTQ community to experience discrimination, specifically in job applications and interactions with police.[50] One-third of LGBTQ Americans believe that the bigger problem is based on laws, and government policies, and the rest believe that it is based on individual prejudice. Due to the experiences of discrimination in public, many LGBTQ Americans tries to avoid situations or places out of fear of discrimination, such as bathrooms, medical care, or calling the police.[51]

A survey by CAP shows that 25.2% of LGBTQ people experienced discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity, and that these discriminations negatively affect their well-being and living environment. Due to the fear of discrimination, many LGBTQ people change their lives such as hiding their relationships, delaying health care, avoid social situations, etc.[52] In research publish by UCLA School of Law, survey data showed that 29.8% of LGBTQ employees experienced workplace discrimination such as being fired or not hired. LGBTQ employees who are people of color were much more likely to report that they didn't get hired because of their sexual orientation or gender identity, compared to white LGBTQ employees. Transgender employees were more likely to face discrimination based on their LGBTQ identity compared to cisgender LGBTQ employees. Almost half (48.8%) of transgender employees experienced discrimination due to their LGBTQ identity, while only 27.8% of cisgender LGBTQ employees reported such experiences. In addition, over half (57.0%) of discriminated LGBTQ employees said their employer or co-workers indicated that the unfair treatment was linked to religious beliefs.[53] In the U.S., certain states have passed laws permitting child welfare agencies to deny services to LGBTQ community based on religious or moral beliefs. Similarly, some states allow healthcare providers to refuse certain procedures or medications for LGBTQ community on religious or moral grounds. Additionally, certain states permit businesses to decline services to LGBTQ people or same-sex couples, particularly in the context of wedding-related services, citing religious or moral beliefs.[54]

In a 2001 study that examined possible root causes of mental disorders in lesbian, gay and bisexual people, Cochran and psychologist Vickie M. Mays, of the University of California, explored whether ongoing discrimination fuels anxiety, depression and other stress-related mental health problems among cisgender LGBTQ people.[55] The authors found strong evidence of a relationship between the two.[55] The team compared how 74 cisgender LGBTQ and 2,844 heterosexual respondents rated lifetime and daily experiences with discrimination such as not being hired for a job or being denied a bank loan, as well as feelings of perceived discrimination.[55] Cisgender LGBTQ respondents reported higher rates of perceived discrimination than heterosexuals in every category related to discrimination, the team found.[55] However, while gay youth are considered to be at higher risk for suicide, a literature review published in the journal Adolescence states, "Being gay in-and-of-itself is not the cause of the increase in suicide." Rather the review notes that the findings of previous studies suggested the,"...suicide attempts were significantly associated with psychosocial stressors, including gender nonconformity, early awareness of being gay, victimization, lack of support, school dropout, family problems, acquaintances' suicide attempts, homelessness, substance abuse, and other psychiatric disorders. Some of these stressors are also experienced by heterosexual adolescents, but they have been shown to be more prevalent among gay adolescents."[56] Despite recent progress in LGBTQ rights, gay men continue to experience high rates of loneliness and depression after coming out.[57]

Multiculturalism

General

LGBTQ multiculturalism is the diversity within the LGBTQ community as a representation of different sexual orientations, gender identities—as well as different ethnic, language, religious groups within the LGBTQ community. At the same time as LGBTQ and multiculturalism relation, may consider the inclusion of LGBTQ community into a larger multicultural model, as for example in universities,[58] such multicultural model includes the LGBTQ community together and equal representation with other large minority groups such as African Americans in the United States.[citation needed]

The two movements have much in common politically. Both are concerned with tolerance for real differences, diversity, minority status, and the invalidity of value judgments applied to different ways of life.[59][60]

Researchers have identified the emergence of gay and lesbian communities during several progressive time periods across the world including: the Renaissance, Enlightenment, and modern Westernization.[61] Depending on geographic location, some of these communities experienced more opposition to their existence than others; nonetheless, they began to permeate society both socially and politically.[61]

European cities past and present

City spaces in Early Modern Europe were host to a wealth of gay activity; however, these scenes remained semi-secretive for a long period of time.[61] Dating back to the 1500s, city conditions such as apprenticeship labor relations and living arrangements, abundant student and artist activity, and hegemonic norms surrounding female societal status were typical in Venice and Florence, Italy.[61] Under these circumstances, many open minded young people were attracted to these city settings.[61] Consequently, an abundance of same-sex interactions began to take place.[61] Many of the connections formed then often led to the occurrence of casual romantic and sexual relationships, the prevalence of which increased quite rapidly over time until a point at which they became a subculture and community of their own.[61] Literature and ballroom culture gradually made their way onto the scene and became integrated despite transgressive societal views.[61] Perhaps the most well-known of these are the balls of Magic-City. Amsterdam and London have also been recognized as leading locations for LGBTQ community establishment.[61] By the 1950s, these urban spaces were booming with gay venues such as bars and public saunas where community members could come together.[61] Paris and London were particularly attracting to the lesbian population as platforms for not only socialization, but education as well.[61] A few other urban occasions that are important to the LGBTQ community include Carnival in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Mardi Gras in Sydney, Australia, as well as the various other pride parades hosted in bigger cities around the world.[61]

Urban spaces in the United States

In the same way in which LGBTQ community used the city backdrop to join socially, they were able to join forces politically as well. This new sense of collectivity provided somewhat of a safety net for individuals when voicing their demands for equal rights.[62] In the United States specifically, several key political events have taken place in urban contexts. Some of these include, but are not limited to:

- Independence Hall, Philadelphia - gay and lesbian protest movement in 1965 – activists led by Barbara Gittings started some of the first picket lines here. These protests continued on and off until 1969.[63] Gittings went on to run the Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Library Association for 15 years.[64]

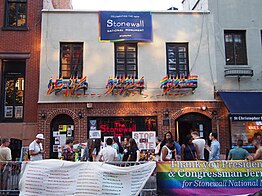

- The Stonewall Inn, on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, Manhattan – the birthplace of the modern gay rights movement in 1969 – for the first time, a group of gay men and drag queens fought back against police during a raid on this small bar in Greenwich Village. The site is now a U.S. National Historic Landmark.[63]

- Castro Street, San Francisco – gathering place for LGBTQ community beginning in the 1970s; this urban spot was an oasis of hopefulness. Home to the first openly gay elected official Harvey Milk and the legendary Castro Theater, this cityscape remains iconic to the LGBTQ community.[63]

- Cambridge, Massachusetts City Hall, was the site of the first same-sex marriage in U.S. history in 2004. Following this event, attempts by religious groups in the area to ban it have been stifled and many more states have joined the Commonwealth.[63]

- AIDS Activities Coordinating Office, Philadelphia – an office to help stop the spread of HIV/AIDS, by providing proper administrative components, direct assistance, and education on HIV/AIDS.[65]

During and following these events, LGBTQ community subculture began to grow and stabilize into a nationwide phenomenon.[66] Gay bars became more and more popular in large cities.[66] For gays particularly, increasing numbers of cruising areas, public bath houses, and YMCAs in these urban spaces continued to welcome them to experience a more liberated way of living.[66] For lesbians, this led to the formation of literary societies, private social clubs, and same-sex housing.[66] The core of this community-building took place in New York City and San Francisco, but cities like St. Louis, Lafayette Park in WA, and Chicago quickly followed suit.[66]

City

Cities afford a host of prime conditions that allow for better individual development as well as collective movement that are not otherwise available in rural spaces.[62] First and foremost, urban landscapes offer LGBTQ community better prospects to meet each other and form networks and relationships.[62] One ideal platform within this framework was the free labor market of many capitalistic societies, which enticed people to break away from their often damaging traditional nuclear families in order to pursue employment in bigger cities.[66] Making the move to these spaces afforded them new liberty in the realms of sexuality, identity, and kinship.[62] Some researchers describe this as a phase of resistance against the confining expectations of normativity.[62] Urban LGBTQ community demonstrated this pushback through various outlets, including their style of dress, the way they talked and carried themselves, and how they chose to build community.[62] From a social science perspective, the relationship between the city and the LGBTQ community is not a one-way street. LGBTQ community give back as much, if not more, in terms of economic contributions (i.e., "pink money"), activism and politics too.[61]

Intersections of race

This section may lend undue weight to a single source. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (September 2021) |

Compared to white LGBTQ people, LGBTQ people of color often experience prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination on the basis of not only their sexual orientation and gender identity, but also on the basis of race.[67] Nadal and colleagues discuss LGBTQ people of color and their experience of intersectional microaggressions which target various aspects of their social identities.[67][68] These negative experiences and microaggressions can come from cisgender and heterosexual white people, cisgender and heterosexual people of their own race,[67] and from the LGBTQ community themselves, which is usually dominated by white people.[67]

Some LGBTQ people of color do not feel comfortable and represented within LGBTQ spaces.[67] A comprehensive and systematic review of the existing published research literature around the experiences of LGBTQ people of color finds a common theme of exclusion in largely white LGBTQ spaces.[67] These spaces are typically dominated by white LGBTQ people, promote White and Western values, and often leave LGBTQ people of color feeling as though they must choose between their racial community or their gender and sexual orientation community.[67] In general, Western society will often subtly code "gay" as white; white LGBTQ people are often seen as the face of LGBTQ culture and values.[67]

The topic of coming out and revealing one's sexual orientation and gender identity to the public is associated with white values and expectations in mainstream discussions.[67] Where white Western culture places value on the ability to speak openly about one's identity with family, one particular study found that LGBTQ participants of color viewed their family's silence about their identity as supportive and accepting.[67] For example, collectivist cultures view the coming out process as a family affair rather than an individual one. Furthermore, the annual National Coming Out Day centers on white perspectives as an event meant to help an LGBTQ person feel liberated and comfortable in their own skin.[67] However, for some LGBTQ people of color, National Coming Out Day is viewed in a negative light.[67][69] In communities of color, coming out publicly can have adverse consequences, risking their personal sense of safety as well as that of their familial and communal relationships.[67] White LGBTQ people tend to collectively reject these differences in perspective on coming out, resulting in possibly further isolating LGBTQ people of color.[67]

See also

References

- ^ Julia Goicochea (August 16, 2017). "Why New York City Is a Major Destination for LGBT Travelers". The Culture Trip. Archived from the original on January 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ Eli Rosenberg (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ "Workforce Diversity The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ^ Jeff Nelson (June 24, 2022). "Madonna Celebrates Queer Joy with Drag Queens, Son David at Star-Studded NYC Pride Party". People Magazine. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ Acronyms, Initialisms & Abbreviations Dictionary, Volume 1, Part 1. Gale Research Co., 1985, ISBN 978-0-8103-0683-7. Factsheet five, Issues 32–36, Mike Gunderloy, 1989 Archived 2015-09-06 at the Wayback Machine[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Hoffman, Amy (2007). An Army of Ex-Lovers: My life at the Gay Community News. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-1558496217.

- ^ Ferentinos, Susan (2014-12-16). Interpreting LGBT History at Museums and Historic Sites (in Arabic). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7591-2374-8. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ Centerlink. "2008 Community Center Survey Report" (PDF). LGBT Movement Advancement Project. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- ^ Shankle, Michael D. (2006). The Handbook of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Public Health: A Practitioner's Guide To Service. Haworth Press. ISBN 978-1-56023-496-8. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ The Santa Cruz County in-queery, Volume 9, Santa Cruz Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgendered Community Center, 1996. 2008-11-01. Archived from the original on 2013-05-10. Retrieved 2011-10-23. page 690

- ^ "Civilities, What does the acronym LGBTQ stand for?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Heidi (2022-08-22). "The Guide to LGBTQ Acronyms: Is it LGBT or LGBTQ+ or LGBTQIA+?". The Center. Retrieved 2023-07-07.

- ^ a b "Symbols of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Movements". Lambda.org. Archived from the original on 4 December 2004. Retrieved 26 December 2004.

- ^ "How A Lavender Rhino Became A Symbol Of Gay Resistance In '70s Boston". www.wbur.org. 3 June 2019. Retrieved 2023-07-07.

- ^ "How the Nazi Regime's Pink Triangle Symbol Was Repurposed for LGBTQ Pride". Time. Archived from the original on 2021-06-07. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- ^ Christen, Simone. "The Irony of the Human Rights Campaign's Logo". The Oberlin Review. Archived from the original on 2021-06-05. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- ^ "Philly's Pride Flag to Get Two New Stripes: Black and Brown". Philadelphia Magazine. 2017-06-08. Archived from the original on 2018-02-26. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- ^ "What We Do". HRC. Archived from the original on 2012-07-31. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ^ "Wiser Earth Organizations: Empowering Spirits Foundation". Wiserearth.org. Archived from the original on 2020-06-29. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ^ GLAAD: "About GLAAD" Archived April 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Amnesty International USA. Human Rights and the Rights of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People. 2009. "About LGBT Human Rights". Archived from the original on 2010-07-12. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered History in America". Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ^ Raley, Amber B.; Lucas, Jennifer L. (October 2006). "Stereotype or Success? Prime-time television's portrayals of gay male, lesbian, and bisexual characters". Journal of Homosexuality. 51 (2): 19–38. doi:10.1300/J082v51n02_02. PMID 16901865. S2CID 9882274.

- ^ Gomestic. 2009. Stanza Ltd

- ^ Gross, Larry P. (2001). Up from Invisibility: Lesbians, Gay Men, and the Media in America. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231119535.

Media's portrayal of gays and lesbians.

- ^ "Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer community | sociology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2019-12-02. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- ^ Kirchick, James (2019-06-28). "The Struggle for Gay Rights Is Over". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2019-11-25. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- ^ Fetto, John. In Broad Daylight – Marketing to the gay community – Brief Article. BNet. February 2001. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-10-16. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Craig, Shelley L.; McInroy, Lauren (2014-01-01). "You Can Form a Part of Yourself Online: The Influence of New Media on Identity Development and Coming Out for LGBTQ Youth". Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 18 (1): 95–109. doi:10.1080/19359705.2013.777007. ISSN 1935-9705. S2CID 216141171. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

- ^ a b c Kitzie, Vanessa (2019). ""That looks like me or something i can do": Affordances and constraints in the online identity work of US LGBTQ+ millennials". Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 70 (12): 1340–1351. doi:10.1002/asi.24217. ISSN 2330-1643.

- ^ a b c DeVito, Michael A.; Walker, Ashley Marie; Birnholtz, Jeremy (2018-11-01). "'Too Gay for Facebook': Presenting LGBTQ+ Identity Throughout the Personal Social Media Ecosystem". Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction. 2 (CSCW): 44:1–44:23. doi:10.1145/3274313. S2CID 53237950.

- ^ a b Fox, Jesse; Warber, Katie M. (2014-12-22). "Queer Identity Management and Political Self-Expression on Social Networking Sites: A Co-Cultural Approach to the Spiral of Silence". Journal of Communication. 65 (1): 79–100. doi:10.1111/jcom.12137. ISSN 0021-9916. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

- ^ Haimson, Oliver L.; Dame-Griff, Avery; Capello, Elias; Richter, Zahari (2019-10-18). "Tumblr was a trans technology: the meaning, importance, history, and future of trans technologies". Feminist Media Studies. 21 (3): 345–361. doi:10.1080/14680777.2019.1678505. hdl:2027.42/153782. ISSN 1468-0777.

- ^ a b c d Simpson, Ellen; Semaan, Bryan (2021-01-05). "For You, or For"You"?". Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction. 4 (CSCW3): 1–34. doi:10.1145/3432951. ISSN 2573-0142. S2CID 230717408. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

- ^ Shelley L. Craig PhD, RSW, LCSW; Lauren McInroy MSW, RSW (2014-01-01). "You Can Form a Part of Yourself Online: The Influence of New Media on Identity Development and Coming Out for LGBTQ Youth". Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 18 (1): 95–109. doi:10.1080/19359705.2013.777007. ISSN 1935-9705. S2CID 216141171. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fox, Jesse; Warber, Katie M. (2014-12-22). "Queer Identity Management and Political Self-Expression on Social Networking Sites: A Co-Cultural Approach to the Spiral of Silence". Journal of Communication. 65 (1): 79–100. doi:10.1111/jcom.12137. ISSN 0021-9916. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

- ^ PRNewswire. "Buying Power of US Gays and Lesbians to Exceed $835 Billion by 2011". January 25, 2007

- ^ Hicklin, Aaron (27 September 2012). "Power of the pink pound". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Hipps, James (24 August 2008). "The Power of Gay: Buying Power That Is". gayagenda.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Miller, Richard K. and Kelli Washington. 2014. " PART IX: SEGMENTATION: Chapter 60: GAY & LESBIAN CONSUMERS." Consumer Behavior. 326–333.

- ^ a b c Um, Nam-Hyun (2012). "Seeking the holy grail through gay and lesbian consumers: An exploratory content analysis of ads with gay/lesbian-specific content". Journal of Marketing Communications. 18 (2): 133–149. doi:10.1080/13527266.2010.489696. S2CID 167786222.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Soat, Molly. 2013. "Demographics in the Modern Day." Marketing News, 47 (9). 1p.

- ^ Gallup, Inc. (20 March 2015). "San Francisco Metro Area Ranks Highest in LGBT Percentage". Gallup.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Mapping the Void: Two-Spirit and LGBTQ+ Experiences in Hamilton" (PDF). 11 Jun 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ "Trans PULSE Canada Report No. 1 or 10". 10 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Jones, Jeffrey M. (3 March 2021). "What Percentage of Americans Are LGBT?". Gallup. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d Oakenfull, Gillian (2012). "Gay Consumers and Brand Usage: The Gender-Flexing Role of Gay Identity". Psychology & Marketing. 29 (12): 968–979. doi:10.1002/mar.20578.

- ^ "Hate crimes based on sexual orientation or gender identity are an aggravating circumstance". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2024-04-26.

- ^ Casey, Logan S.; Reisner, Sari L.; Findling, Mary G.; Blendon, Robert J.; Benson, John M.; Sayde, Justin M.; Miller, Carolyn (December 2019). "Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans". Health Services Research. 54 (Suppl 2): 1454–1466. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13229. ISSN 0017-9124. PMC 6864400. PMID 31659745.

- ^ Prichep, Deena (25 November 2017). "For LGBTQ People Of Color, Discrimination Compounds". NPR. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ Avenue, 677 Huntington; Boston; Ma 02115 (2017-11-21). "Poll finds a majority of LGBTQ Americans report violence, threats, or sexual harassment related to sexual orientation or gender identity; one-third report bathroom harassment". News. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Widespread Discrimination Continues to Shape LGBT People's Lives in Both Subtle and Significant Ways". Center for American Progress. 2017-05-02. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ thisisloyal.com, Loyal |. "LGBT People's Experiences of Workplace Discrimination and Harassment". Williams Institute. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ Thoreson, Ryan (2018-02-19). ""All We Want is Equality"". Human Rights Watch.

- ^ a b c d Mays, Vickie M.; Cochran, Susan D. (2001). "Mental Health Correlates of Perceived Discrimination Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults in the United States" (PDF). American Journal of Public Health. 91 (11): 1869–1876. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1869. PMC 1446893. PMID 11684618. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-29. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ Kitts, R. (2005). "Gay adolescents and suicide: understanding the association". Adolescence. 40 (159): 621–628. PMID 16268137.

- ^ Hobbes, Michael (2017-03-01). "Together Alone: the Epidemic of Gay Loneliness". The Huffington Post Highline. Archived from the original on 2020-06-17. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ LGBT Affairs Archived 2014-05-13 at the Wayback Machine, University of Florida

- ^ John Corvino, "The Race Analogy" Archived 2015-04-11 at archive.today, The Huffington Post, accessed Saturday 11 April 2015, 10:39 (GMT)

- ^ Konnoth, Craig J. (2009). "Created in Its Image: The Race Analogy, Gay Identity, and Gay Litigation in the 1950s–1970s". The Yale Law Journal. 119 (2): 316–372. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Aldrich, Robert (2004). "Homosexuality and the City: An Historical Overview". Urban Studies. 41 (9): 1719–1737. Bibcode:2004UrbSt..41.1719A. doi:10.1080/0042098042000243129. S2CID 145411558.

- ^ a b c d e f Doderer, Yvonne P. (2011). "LGBTQs in the City, Queering Urban Space". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 35 (2): 431–436. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.01030.x. PMID 21542205. Archived from the original on 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- ^ a b c d Polly, J. (2009). Top 10 Historic Gay Places in the U.S. Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, 16(4), 14–16.

- ^ Goulart, Karen M. (8 March 2001). "Library opens Gittings Collection". No. A1, A23, A24. Philadelphia Gay News.

- ^ "Mayor's Commission on Sexual Minorities Fiscal Year 1988 Recommendations Pertaining to AIDS". City of Philadelphia. Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries.

- ^ a b c d e f D'Emilio, J. (1998). CHAPTER 13: Capitalism and Gay Identity. In “Culture, Society & Sexuality” (pp. 239–247). Taylor & Francis Ltd / Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Sadika, Bidushy; Wiebe, Emily; Morrison, Melanie A.; Morrison, Todd G. (2020-03-02). "Intersectional Microaggressions and Social Support for LGBTQ Persons of Color: A Systematic Review of the Canadian-Based Empirical Literature". Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 16 (2): 111–147. doi:10.1080/1550428X.2020.1724125. ISSN 1550-428X.

- ^ Nadal, Kevin L.; Davidoff, Kristin C.; Davis, Lindsey S.; Wong, Yinglee; Marshall, David; McKenzie, Victoria (August 2015). "A qualitative approach to intersectional microaggressions: Understanding influences of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and religion". Qualitative Psychology. 2 (2): 147–163. doi:10.1037/qup0000026. ISSN 2326-3598.

- ^ Ghabrial, Monica A. (March 2017). ""Trying to Figure Out Where We Belong": Narratives of Racialized Sexual Minorities on Community, Identity, Discrimination, and Health". Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 14 (1): 42–55. doi:10.1007/s13178-016-0229-x. ISSN 1868-9884. S2CID 148442076.

Further reading

- Murphy, Timothy F., Reader's Guide to Lesbian and Gay Studies, 2000 (African American LGBTQ community, and also its relation to art). Partial view at Google Books.