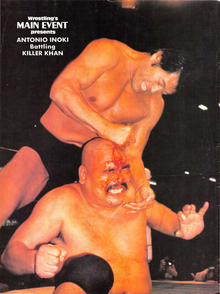

Antonio Inoki

Antonio Inoki | |

|---|---|

Inoki in 2012 | |

| Member of the House of Councillors | |

| In office July 23, 1989 – July 22, 1995 | |

| In office July 29, 2013 – July 28, 2019 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Kanji Inoki (猪木寛至, Inoki Kanji) February 20, 1943[1] Yokohama, Empire of Japan[2] |

| Died | October 1, 2022 (aged 79)[3] Tokyo, Japan[3] |

| Political party | Democratic Party for the People (2019) |

| Other political affiliations | Sports and Peace Party (1989–1995) Japan Restoration Party (2013–2014) Party for Future Generations (2014–2015) Assembly to Energize Japan (2015–2016) Independents Club (2016–2019) |

| Spouse(s) | Diana Tuck (separated after 1965) A third wife

(m. 1989; div. 2012)Tazuko Tada

(m. 2017; died 2019) |

| Children | 3, including Hiroko Inoki |

| Relatives | Simon Inoki (son-in-law)[4] Hirota Inoki (grandson)[5] Naoto Inoki (grandson)[5] |

| Ring name(s) | Antonio Inoki The Kamikaze Kanji Inoki Kazimoto Killer Inoki Kinji Onoki Little Tokyo Moeru Toukon Tokyo Tom |

| Billed height | 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m)[2] |

| Billed weight | 224 lb (102 kg)[2] |

| Billed from | Tokyo, Japan |

| Trained by | Rikidōzan Karl Gotch |

| Debut | September 30, 1960[6] |

| Retired | April 4, 1998[2][6] |

| Part of a series on |

| Professional wrestling |

|---|

|

Antonio Inoki (アントニオ猪木, Antonio Inoki, born Kanji Inoki (Japanese: 猪木寛至, Hepburn: Inoki Kanji) and later Muhammad Hussain Inoki (Arabic: محمد حسين اينوكي, romanized: Muhamad Husayn Aynwky); February 20, 1943 – October 1, 2022) was a Japanese professional wrestler, professional wrestling trainer, martial artist, politician, and promoter of professional wrestling and mixed martial arts (MMA). He is best known as the founder and 33-year owner of New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW). He is considered to be one of the most influential professional wrestlers of all time,[7][8][9] and one of the biggest key influences on MMA in Japan and internationally.[10][9]

After spending his adolescence in Brazil, Inoki began his professional wrestling career in the 1960s for the Japan Pro Wrestling Alliance (JWA) under the tutelage of Rikidōzan. After he changed his in-ring moniker to Antonio Inoki in 1963, a homage to accomplished Italian wrestler Antonino Rocca, Inoki became one of the most popular stars in Japanese professional wrestling. He is credited with developing strong style and shoot style wrestling in the 1970s and 1980s. He parlayed his wrestling career into becoming one of Japan's most recognizable athletes, a reputation bolstered by his 1976 fight against world champion boxer Muhammad Ali – a fight that served as a predecessor to modern day MMA. In 1995, with Ric Flair, Inoki headlined two shows in North Korea that drew 165,000 and 190,000 spectators, the highest attendances in professional wrestling history.[11] Inoki wrestled his retirement match on April 4, 1998 against Don Frye, and was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2010.[2] Inoki was a twelve-time professional wrestling world champion, notably being the inaugural IWGP Heavyweight Champion and the first Asian WWF Heavyweight Champion (and one of only four overall WWF/WWE Champions of Asian descent, the others being The Iron Sheik, Batista, and Jinder Mahal) – a reign not officially recognized by WWE.

Inoki began his promoting career in 1972, when he founded New Japan Pro-Wrestling. He remained the owner of NJPW until 2005 when he sold his controlling share in the promotion to the Yuke's video game company. In 2007, he founded the Inoki Genome Federation (IGF). In 2017, Inoki founded ISM and the following year left IGF. He was also a co-creator of the karate style Kansui-ryū (寛水流, Kansui-ryū) along with Matsubayashi-ryū master Yukio Mizutani.[12]

In 1989, while still an active wrestler, Inoki entered politics as he was elected to the Japanese House of Councillors. During his first term with the House of Councillors, Inoki successfully negotiated with Saddam Hussein for the release of Japanese hostages before the outbreak of the Gulf War. His first tenure in the House of Councillors ended in 1995, but he was reelected in 2013. In 2019, Inoki retired from politics.

Early life

[edit]Kanji Inoki was born into an affluent family in Yokohama on February 20, 1943. He was the sixth son and the second-youngest of the seven boys and four girls. His father, Sajiro Inoki, a businessman and politician, died when Kanji was five years old. Inoki was taught karate by an older brother while in 6th grade. By the time he was in 7th grade at Terao Junior High School, he was 5 feet 11 inches tall and joined the basketball team. He later quit and joined a track and field club as a shot putter. He eventually won the championship at the Yokohama Junior High School track and field competition.

The family fell on hard times in the post-war years, and in 1957, the 14-year-old Inoki emigrated to Brazil with his grandfather, mother, and brothers. His grandfather died during the journey to Brazil. Inoki won regional championships in Brazil in shot put, discus throw, and javelin throw, and finally the All Brazilian championships in the shot put and discus.[13]

Professional wrestling career

[edit]Early career (1960–1971)

[edit]Inoki met Rikidōzan at the age of 17 in Brazil and went back to Japan for the Japan Pro Wrestling Alliance (JWA) as his disciple. He trained in the JWA dojo under the renowned Karl Gotch, complementing further his training under amateur wrestler Isao Yoshiwara and kosen judoka Kiyotaka Otsubo.[14] One of his dojo classmates was Giant Baba. After Rikidozan's murder, Inoki worked in Baba's shadow until he left for an excursion to the United States in 1964.

After a long excursion of wrestling in the United States, Inoki found a new home in Tokyo Pro Wrestling in 1966. While there, Inoki became their biggest star. The company folded in 1967, due to turmoil behind the scenes.

Returning to JWA in late 1967, Inoki was made Baba's partner and the two dominated the tag team ranks as the "B-I Cannon", winning the NWA International Tag Team Championship belts four times.

On May 16, 1969, during the 11th World Big League, Inoki stopped Giant Baba's fourth consecutive victory and won his first tournament.

In July 1969, when NET (currently TV Asahi) started broadcasting Japanese professional wrestling, Inoki was the ace of NET's wrestling broadcasts, as Baba's matches were monopolized by Nippon TV under the agreement between the JWA and Nippon TV. On December 2, 1969, he challenged Dory Funk Jr. for the NWA World Heavyweight Championship, and on March 26, 1971, won the NWA United National Championship.

New Japan Pro-Wrestling (1972–2005)

[edit]

Fired from JWA in late 1971 for planning a takeover of the promotion, Inoki founded New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW) in 1972. His first match as a New Japan wrestler was against Karl Gotch. In 1975 he faced Lou Thesz, with Inoki taking a vicious Greco-Roman backdrop within the first seconds of the match.

In 1976, Inoki fought with Pakistani Akram Pahalwan in a special rules match. The match apparently turned into a shoot, with an uncooperative Akram biting Inoki in the arm and Inoki retaliating with an eye poke. At the end, Inoki won the bout with a double wrist lock, injuring Pahalwan's arm after the latter refused to submit. According to referee Mr. Takahashi, this finish was not scripted and was fought for real after the match's original flow became undone.[15]

On December 8, 1977, Inoki was involved in a match against former strongman turned professional wrestler Antonio Barichievich better known as The Great Antonio. Barichievich inexplicably began no-selling Inoki's attacks and then stiffing Inoki; Inoki responded by shooting on Barichievich, retaliating with a series palm strikes, grounding him with a single leg takedown and following with up repeated kicks, and then stomping his head repeatedly as he lay on the mat before the match was stopped.[16]

In June 1979, Inoki wrestled Akram's countryman Zubair Jhara Pahalwan, this time in a regular match, and lost the fight in the fifth round.[17] In 2014, 22 years after Zubair Jhara's death, he announced he would take Jhara's nephew Haroon Abid under his guardianship.[18]

On November 30, 1979, Inoki defeated WWF Heavyweight Champion Bob Backlund in Tokushima, Japan, to win the championship.[19] Backlund then won a rematch on December 6. However, WWF president Hisashi Shinma declared the re-match a no contest due to interference from Tiger Jeet Singh, and Inoki remained champion. Inoki refused the title on the same day, and it was declared vacant. Backlund later defeated Bobby Duncum in a Texas Death match to regain the title on December 12. Inoki's reign is not recognized by WWE in its WWF/WWE title history and Backlund's first reign is viewed as uninterrupted from 1978 to 1983.

In 1995, Inoki and the North Korean government came together to hold a two-day wrestling festival for peace in Pyongyang, North Korea. The event drew 165,000 and 190,000 fans respectively to Rungnado May Day Stadium. The main event saw the only match between Inoki and Ric Flair, with Inoki coming out on top.[11] Days before this event, Inoki and the Korean press went to the grave and birthplace of Rikidōzan and paid tribute to him.

Inoki's retirement from professional wrestling matches came with the staging of the "Final Countdown" series between 1994 and 1998. This was a special series in which Inoki re-lived some of his martial arts matches under traditional professional wrestling rules, as well as rematches of some of his most well known wrestling matches. As part of the Final Countdown tour, Inoki made a rare World Championship Wrestling appearance; defeating WCW World Television Champion Steven Regal in a non-title match at Clash of the Champions XXVIII. On April 4, 1998, Inoki defeated Don Frye in the final official match of his professional wrestling career.[20] After his retirement in 1998, Inoki founded a new wrestling promotion, the Universal Fighting-Arts Organization (UFO).

Inoki would later participate in four exhibition matches after his retirement. On March 11, 2000, at a Rikidōzan memorial event, Inoki was defeated by Japanese actor and singer Hideaki Takizawa; later that year during a New Year's Eve event, he wrestled Brazilian mixed martial artist Renzo Gracie to a time limit draw. On December 31, 2001, he teamed with The Great Sasuke to defeat Giant Silva and Red & White Mask;[21] two years later, on December 31, 2003, Inoki wrestled the final match of his career, facing Tatsumi Fujinami as part of Fujinami's retirement ceremony.[22]

In 2005, Yuke's, a Japanese video company, purchased Inoki's controlling 51.5% stock in New Japan.[23][24]

Post NJPW years (2005–2022)

[edit]In 2007, Inoki founded a new promotion called Inoki Genome Federation (IGF).[citation needed]

On February 1, 2010, World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) announced on its Japanese website that Inoki would be inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame. Inoki was presented with a Hall of Fame certificate by WWE's Ed Wells.[citation needed]

In 2017, Inoki created a new company, ISM. ISM held its first event on June 24 of that year. On March 23, 2018, Inoki left IGF.[citation needed]

In October 2019, Inoki appeared at a Pro Wrestling Zero1 event at the Yasukuni Shrine, which is controversial for its relation to World War II.[25]

In August 2022, Inoki established the Inoki Genki Factory to serve as his official management company.[26] It was later reported that the Inoki Genki Factory was looking into the idea of hosting professional wrestling and mixed martial arts events.[26]

Political career

[edit]House of Councillors

[edit]1989–1995: First stint

[edit]Following in his father's footsteps, Inoki entered politics in 1989, when he was elected into the House of Councillors as a representative of his own Sports and Peace Party in the 1989 Japanese House of Councillors election. Inoki's win secured him among the highest offices ever won by a professional wrestling personality in politics. The Sports and Peace Party later formed a parliamentary alliance with the Democratic Socialist Party.[27] On October 14, 1989, Inoki was stabbed during a political event in Aizuwakamatsu, Fukushima Prefecture.[27]

Imitating Muhammad Ali, Inoki traveled to Iraq in 1990 in "an unofficial one-man diplomatic mission" to negotiate with Saddam Hussein for the release of Japanese hostages before the outbreak of the Gulf War.[28] He personally organized a wrestling event in Iraq to entice Saddam to free the 41 captive Japanese nationals, this ultimately proved to be a success with 36 Japanese nationals freed.[29] Inoki subsequently retained his seat in the 1992 Japanese House of Councillors election. He failed to win re-election in the 1995 Japanese House of Councillors election following a number of scandals reported in 1994, and left politics for the next eighteen years.[30]

2013–2019: Second stint

[edit]

On June 5, 2013, Inoki announced that he would again run for a House of Councillors seat in the National Diet under the Japan Restoration Party ticket.[30][31] Inoki won the election to return to Japan's Upper House as an MP.[32][33][34]

In November 2013, he was suspended from the Diet for 30 days because of an unauthorized trip to North Korea.[35] He had visited on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the armistice in the Korean War, and had met with senior North Korean figure Kim Yong-nam during his visit.[36] This was Inoki's 27th visit to North Korea; he explained in an interview that the North Korean abductions of Japanese citizens had caused the Japanese government to "close the door" on diplomacy with the North, but that the issue would not be resolved without ongoing communication, and that he saw his relationship with North Korean-born Rikidōzan as a crucial link to the people of the North.[37]

He was reportedly considering running for governor of Tokyo in 2014 following another visit to North Korea.[38]

Inoki joined the splinter of the Japan Restoration Party, Party for Future Generations, in 2014. In January 2015, he helped to establish a new party named the Assembly to Energize Japan, which he left in 2016, to sit in the Independents Club.

In September 2017, Inoki re-established his position that Japan should make more of an effort to have co-operative dialogue with North Korea, in the wake of North Korea launching ballistic missiles over Hokkaido. This was succeeded by another of Inoki's controversial trips to the nation.[39]

In June 2019, Inoki announced his retirement from politics.[40]

Other positions

[edit]On June 23, 1989, Inoki founded the Sports and Peace Party, his own political party.[41][27] Inoki served as the party's leader until the 1998 House of Councillors election when he was succeeded by Iichi Nishime. In 2002, Inoki was appointed a Goodwill Ambassador of Palau;[42] Inoki would again be appointed a Japanese Goodwill Ambassador to Palau in 2013.[43][44]

From August 2014 until December 2014, Inoki served as the director of the National Sports Bureau of the Party for Future Generations and as a chairperson of the Policy Research Committee of the House of Councillors.[27] On March 1, 2015, Inoki was appointed as a Goodwill Ambassador for the 2016 Summer Olympics by the National Olympic Committee of Cambodia.[27] From 2015 until 2016, Inoki served as the supreme advisor of the Assembly to Energize Japan, a political party he co-founded with Kota Matsuda.

Mixed martial arts involvement

[edit]Inoki was amongst the group of professional wrestlers who were tutored in the art of hooking and shooting by the professional wrestler Karl Gotch. This method of wrestling taught to Inoki by Gotch borrowed heavily from professional wrestling's original catch wrestling roots, and is one of the most important influences of modern shoot wrestling. Inoki named his method of fighting "strong style" and it is sometimes referred to as "Inokiism".

Inoki faced many opponents from all dominant disciplines of combat from various parts of the world, such as boxers, judoka, karateka, kung fu practitioners, sumo wrestlers, and fellow professional wrestlers. These bouts included a match with then-prominent karate competitor Everett Eddy.[45] Eddy had previously competed in a mixed skills bout against boxer Horst Geisler and lost by knockout.[46] The bout with Eddy ended with the karateka knocked out by a professional wrestling powerbomb followed by a Hulk Hogan-esque leg drop. Another such match pitted Inoki against 6'7" Kyokushin karate stylist Willie Williams, who had allegedly fought a bear for a 1976 Japanese film titled The Strongest Karate 2.[47] This bout ended when a doctor stopped the fight after both competitors repeatedly fell out of the ring.[48] Although many of the matches were predetermined and scripted, they are seen as a precursor to modern mixed martial arts (MMA). When asked about Inoki's fighting skills, business colleague Carlson Gracie stated Inoki was "one of the best fighters he'd seen."[49]

His most famous bout was against heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali on June 26, 1976, in Tokyo.[50] Inoki initially promised Ali a predetermined match to get him to fight in Japan, but when the deal materialized, Ali's camp feared that Inoki would turn the fight into a shoot, which many believe was Inoki's intention. Ali visited a professional wrestling match involving Inoki and witnessed Inoki's grappling ability. The rules of the match were announced several months in advance. Two days before the match, however, several new rules were added which severely limited the moves that each man could perform. One rule change, specifying that Inoki could only throw a kick if one of his knees was on the ground, had a major effect on the outcome of the fight.[50] Ali landed a total of six punches to Inoki, and Inoki kept to his back in a defensive position for almost the entire duration of the match of 15 rounds, hitting Ali with a low kick repeatedly.[51] The bout ended in a draw, 3–3. Ali left without a press conference and suffered damage to his legs as a result of Inoki's repeated kicks.[52]

Following his retirement from professional wrestling, Inoki promoted a number of MMA events such as UFO Legend, NJPW Ultimate Crush (which showcased pro wrestling matches and MMA matches on the same card), and the annual Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye shows which took place on New Year's Eve in 2000, 2001, 2002, and 2003. Some of the major attractions of these events involved the best of NJPW against world-renowned fighters in legitimate MMA matches. Inoki faced mixed martial artist Renzo Gracie in an exhibition match at the 2000 Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye.

On August 28, 2002, Inoki participated in the Shockwave event co-promoted by K-1 and the Pride Fighting Championships; with a reported attendance of 91,107, Shockwave remains the highest attended live event in MMA's history.[53] The event's opening ceremony saw Inoki dropping into the National Stadium by parachute and then being joined by Hélio Gracie.[54] After being dubbed the "founding fathers of MMA", the two lit a ceremonial Olympic Torch together.[54]

Future UFC Light Heavyweight Champion Lyoto Machida began his career in MMA under the management of Inoki. Machida was described by Inoki as a symbolic "successor" figure for himself, as Naoya Ogawa and Kazuyuki Fujita had been in the past.[55] In 2003, Inoki co-founded the Brazilian MMA promotion Jungle Fight with Wallid Ismail.[56] Inoki was also the ambassador for the International Fight League's Tokyo entry before that promotion's demise. Additionally, Inoki's Inoki Genome Federation promoted both professional wrestling matches and mixed martial arts fights.

Personal life

[edit]Inoki had 10 siblings. His brother Juichi Sagara[57] was a karate master and is credited with bringing Shōtōkan to Brazil.[58][59] Inoki's brother Pablo Inoki, a tenor and political activist, once led the Inoki-founded Sports and Peace Party.[60]

Inoki married American woman Diana Tuck (also known as Linda Tuck) in 1965.[61] The couple would have a daughter together, but separated two years later.[61] Inoki's daughter later died at age 8.[62] Inoki was married to actress Mitsuko Baisho from 1971 to 1987, and together they had a daughter, Hiroko.[63] Inoki married for a third time in 1989,[61] with his third wife giving birth to Inoki's first son.[61] The couple divorced in 2012.[61] Inoki's son later attended Columbia University in New York City.[64] In 2014, Inoki took Haroon Abid, nephew of his Pakistani rival Zubair Jhara Pahalwan, under his guardianship.[18][65] Inoki's fourth[66] wife, Tazuko Tada, died on August 27, 2019.[67] Inoki has two grandsons, Hirota and Naoto Inoki. Hirota was a swimmer at Santa Monica College,[68] having previously set school records in swimming at El Segundo High School.[69] In June 2023, Hirota was appointed to the board of directors of the Inoki Genki Factory.[70] In January 2024, it was reported that Naoto was training in professional wrestling under Katsuyori Shibata,[71] having previously trained under the staff of the L.A. Inoki Dojo.[72] Naoto additionally trains in mixed martial arts (MMA) at Black House MMA.[73] On July 20, 2024, Naoto made his professional wrestling debut, defeating Casanova at a Backyard Squabbles event.[74]

Inoki converted to Shia Islam in 1990 during a pilgrimage to Karbala, the Shiite holy city in Iraq. He was in Iraq negotiating for the release of several Japanese hostages.[75] While in Iraq, Inoki was bestowed the Islamic moniker Muhammad Hussain Inoki (Arabic: محمد حسين اينوكي, romanized: Muhamad Husayn Aynwky), later reportedly describing himself as both a Muslim convert and a Buddhist.[76][77][78] In 2014, Inoki said he was "usually a Buddhist".[28]

Inoki operated a wrestling themed restaurant in Shinjuku, Tokyo, named Antonio's Inoki Sakaba Shinjuku.[79] Inoki is the namesake of two islands, the Inoki Friendship Island in Cuba and the Inoki Island in Palau.[80][44] In 2021, it was reported that spinal issues had confined Inoki to a wheelchair.

Death and legacy

[edit]On October 1, 2022 (September 30 in Eastern Time), at age 79, Inoki died from systemic transthyretin amyloidosis.[3][81][82]

American professional wrestling promotion WWE paid tribute to Inoki on the September 30 episode of SmackDown.[83] On October 1, at Royal Quest II in London, England, New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW) held a ten-bell salute for Inoki.[84] Numerous other Japanese promotions would additionally hold ten-bell salutes for Inoki in the weeks and months following his death. NPB team Yokohama DeNA BayStars would play Inoki's theme song, "Inoki Bombaye" (itself a remix of "Ali Bombaye (Zaire Chant) I" from Muhammad Ali's 1977 biographical film), at their games as a tribute to Inoki following his death.[85][86]

On October 4, NJPW announced that they had made Inoki the promotion's Honorary Chairman for Life prior to his passing.[87] On October 10, during Declaration of Power, the first NJPW event held in Japan since Inoki's death, the promotion held a second ten-bell salute for Inoki.[88]

On December 28, Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye x Ganryujima, a memorial show honoring Inoki, was organized by the Inoki Genki Factory in collaboration with Samurai Warriors Ganryujima and NJPW.[89] Three days later, on December 31, mixed martial arts promotion Rizin held their Rizin 40 event as a memorial for Inoki.[90] On January 4, 2023, NJPW held their Wrestle Kingdom 17 event in tribute to Inoki.[91] On June 9, NJPW, All Japan Pro Wrestling, and Pro Wrestling Noah held All Together: Again to celebrate Inoki's legacy.[92]

On January 16, 2023, Inoki was posthumously awarded the Order of the Rising Sun by the Government of Japan.[93] On that same day, it was announced that Inoki had been awarded the Junior Fourth Rank in Japan's ikai court ranks system.[93] On June 9, the Japan Anniversary Association declared October 1 to be Antonio Inoki Fighting Spirit Day.[94] On September 9, a statue of Inoki was unveiled at the Sojiji Temple in Yokohama.[95]

America's All Elite Wrestling held an event on October 1, 2023, the one-year anniversary of Inoki's death, titled WrestleDream that was organized in honor of Inoki.[96] WrestleDream has since been established as an annual event held by AEW in tribute to Inoki.[97]

On December 14, 2024, the Antonio Inoki Memorial Show was organized in Shanghai, China by NJPW and various Asia-Pacific Federation of Wrestling promotions.[98]

Two of Inoki's former students, Durango Kid and Laberinto, currently run a lucha libre promotion that bears his name, Inoki Sports Management.[99] The two also serve as the head trainers of a wrestling school named the L.A. Inoki Dojo.[99]

In media

[edit]A character based on Inoki called "Kanji Igari" appears in the Japanese manga series Baki the Grappler by Keisuke Itagaki.[100]

Inoki appears in the manga Tiger Mask, in a secondary role: he is the only one who was able to win over Naoto "Tiger Mask" Date, with the two subsequently becoming best friends.

Under the names "Kanta Inokuma" and "Armand Inokuma", Inoki appears in the manga Rasputin the Patriot by Takashi Nagasaki and Junji Itō, a manga heavily based on the book Trap of the State written by ex-diplomat and political writer Masaru Satō. This manga reveals Inoki's experience when he visited Russia to meet with vice president of the Soviet Union Gennady Yanayev in May 1991, three months before the Soviet coup attempt. According to the manga, Inoki correctly predicted that Yanayev would be the one to lead the coup d'état attempt in August.

Inoki appeared in the film The Bad News Bears Go to Japan as himself. A subplot in his scenes involved Inoki seeking a rematch with Ali. Gene LeBell, who also appears in these scenes as a manager of Inoki's scheduled opponent, Mean Bones Beaudine, was the referee of Inoki's match with Ali. Inoki's appearance in the film culminates with a match against the main character, Marvin Lazar (played by Tony Curtis), when Beaudine suddenly becomes unavailable to participate. Professional wrestler Héctor Guerrero served as Curtis's stunt double for the wrestling portions of this scene.

Inoki had the starring role in the film Acacia directed by Jinsei Tsuji.[101]

In Oh!Great's manga Air Gear, Inoki is regularly referred to by the author, and by the manga's characters as an influence on their fighting style. The manga also makes several references to Inoki's large chin. Along with Inoki, fellow wrestler Steve Austin of the World Wrestling Federation has been referred to in Air Gear's pages.

Inoki made an appearance as the guest in 2005 Doraemon episode "The Pitch-Black Pop Stars", where he wrestled Gian after he splashed ink on his face.

Inoki is the inspiration for the wrestling legend Iron Kiba, from the manga Koukou Tekkenden Tough.

Several episodes of the Japanese comedy show Downtown no Gaki no Tsukai ya Arahende!!, most notably 2007's "Do Not Laugh at the Hospital" and 2009's "Do Not Laugh as a Hotel Man", have included parodies of Inoki. In the former, three "patients" are presented as being Inoki, with each imitating Inoki's in-ring persona; while in the latter, the guest known only as "Shin Onii" was asked to imitate Inoki as if he were a hotel bellhop.

In May 2021, Inoki appeared on the Vice on TV series Dark Side of the Ring in an episode covering the 1995 Collision in Korea event.[102]

In 2023, Inoki was the subject of a documentary film, Looking for Antonio Inoki.[103]

Wrestlers trained

[edit]- Adam Pearce[99]

- Akira Jo

- Alex Koslov

- Akira Maeda[104]

- Amazing Kong[105]

- American Balloon

- Aaron Aguilera[105]

- Atsushi Sawada

- Bad News Allen[104]

- Bobby Quance[105]

- Brad Bradley[105]

- Brian Adams[104]

- Bryan Danielson[99]

- Chad Wicks[105]

- Christopher Daniels[99]

- CM Punk[99]

- Daniel Puder

- Dru Onyx

- Durango Kid[106]

- Finn Bálor

- Hartley Jackson[107][108]

- Heddi Karaoui[104]

- Hideki Suzuki

- Hiroshi Hase[104]

- Hisakatsu Oya[104]

- Jimmy Ambriz[105]

- Jose Moreno[105]

- Ivan Gomes[109]

- Joanie Laurer

- Joey Ryan[105]

- José the Assistant

- Josh Barnett[110]

- Jushin Thunder Liger

- Justin McCully[105]

- Justin White

- Karl Anderson[99]

- Katsuyori Shibata

- Kazunari Murakami

- Kazuyuki Fujita[104]

- Keiji Muto[104]

- Kendo Kashin

- Kengo Kimura[104]

- Kohei Sato[105]

- Kotetsu Yamamoto

- Laberinto[106]

- Masahiro Chono[104]

- Masakatsu Funaki

- Masanobu Kurisu[104]

- Mikey Nicholls

- Minoru Suzuki

- Misterioso Jr.

- Naoya Ogawa[104]

- Nobuhiko Takada[104]

- Osamu Kido[104]

- Ricky Reyes[111]

- Riki Choshu[104]

- Rocky Romero[104][99]

- Salman Hashimikov[112]

- Sara Del Rey

- Satoru Sayama[104]

- Sean McCully

- Sinn Bodhi

- Shane Eitner[105]

- Shelly Martinez[113]

- Shinsuke Nakamura[104]

- Shinya Hashimoto[104]

- Samoa Joe[99]

- Tadao Yasuda[104]

- Tatsumi Fujinami[104]

- Tatsutoshi Goto[104]

- The Iceman[105]

- Tian Bing[104]

- Tiger Ali Singh[114]

- TJP[115][99]

- Tommy Williams[105]

- Victor Zangiev[104]

- Willem Ruska

- Yamiki[104]

- Yoshiaki Fujiwara[104]

Exhibition boxing record

[edit]| 1 fight | 0 wins | 0 losses |

|---|---|---|

| Draws | 1 | |

| No. | Result | Record | Opponent | Type | Round, time | Date | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Draw | 0-0-1 | PTS | 15 | Jun 25, 1976 | Under special boxing-wrestling rules. |

Championships and accomplishments

[edit]- Cauliflower Alley Club

- Lou Thesz Award (2004)

- George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2005

- International Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2021[116]

- Japan Pro Wrestling Alliance

- NWA International Tag Team Championship (4 times) – with Shohei Baba

- All Asia Tag Team Championship (4 times) – with Michiaki Yoshimura (3) and Kintarō Ōki (1)

- 11th World Big League

- 1st World Tag League with Kantaro Hoshino

- 2nd World Tag League with Seiji Sakaguchi

- National Wrestling Federation

- New Japan Pro-Wrestling

- IWGP Heavyweight Championship (1 time)

- IWGP Heavyweight Championship (original version) (2 times)

- NWA North American Tag Team Championship (Los Angeles/Japan version) (1 time) – with Seiji Sakaguchi

- Real World Championship (1 time)

- IWGP League (1984, 1986, 1987, 1988)

- Japan Cup Tag Team League (1986) with Yoshiaki Fujiwara

- MSG League (1978–1981)

- MSG Tag League (1980) with Bob Backlund

- MSG Tag League (1982) with Hulk Hogan

- MSG Tag League (1983) with Hulk Hogan

- MSG Tag League (1984) with Tatsumi Fujinami

- Six Man Tag Team Cup League (1988) with Riki Choshu & Kantaro Hoshino[117]

- World League (1974, 1975)

- Greatest 18 Club inductee

- Greatest Wrestlers (Class of 2007)[118]

- NWA Big Time Wrestling

- NWA Hollywood Wrestling

- NWA North American Tag Team Championship (Los Angeles/Japan version) (1 time) – with Seiji Sakaguchi

- NWA United National Championship (1 time)

- NWA Mid-America

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum

- Pro Wrestling Illustrated

- Ranked No. 16 of the 500 best singles wrestlers in the PWI 500 in 1995

- Ranked No. 5 of the 500 best singles wrestlers during the "PWI Years" in 2003

- Ranked No. 12, and 44 of the 100 best tag team of the "PWI Years" with Tatsumi Fujinami and Hulk Hogan, respectively, in 2003

- Lifetime Achievement Award[121]

- Stanley Weston Award (2018)[122]

- Pro Wrestling This Week

- Wrestler of the Week (June 7–13, 1987)[123]

- Tokyo Pro Wrestling

- United States Heavyweight Championship (1 time)

- Tokyo Sports

- 30th Anniversary Lifetime Achievement Award (1990)[124]

- 50th Anniversary Lifetime Achievement Award (2010)[125]

- Best Tag Team Award (1975) with Seiji Sakaguchi[126]

- Best Tag Team Award (1981) with Tatsumi Fujinami[127]

- Distinguished Service Award (1979, 1982)[126][127]

- Lifetime Achievement Award (1989, 2022)[127][128]

- Match of the Year Award (1974) vs. Strong Kobayashi on March 19[126]

- Match of the Year Award (1975) vs. Billy Robinson on December 11[126]

- Match of the Year Award (1979) with Giant Baba vs. Abdullah the Butcher and Tiger Jeet Singh on August 26[126]

- Match of the Year Award (1984) vs. Riki Choshu on August 2[127]

- MVP Award (1974, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1980, 1981)[126][127]

- Special Grand Prize (1983, 1987)[127]

- Technique Award (1985)[127]

- Universal Wrestling Association

- World Championship Wrestling

- World Wide Wrestling Federation/World Wrestling Federation/World Wrestling Entertainment

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter

Decorations received by Inoki

[edit]| Award or decoration | Country | Date | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order of the Southern Cross | December 20, 1974 | [130] | ||

| Order of Friendship | September 15, 2010 | [27][131][132] | ||

| Friendship Medal | November 20, 2012 | [133] | ||

| Order of the Rising Sun | January 16, 2023 | [93] | ||

| N/A | Junior Fourth Rank | January 16, 2023 | [93] | |

References

[edit]- ^ "Power Slam". This Month in History: February. SW Publishing. January 1999. p. 28. 55.

- ^ a b c d e "Antonio Inoki's WWE Hall of Fame profile". WWE. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ a b c アントニオ猪木さん死去 プロレス界の巨星堕つ. Tokyo Sports (in Japanese). 1 October 2022. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Lambert, Jeremy (16 January 2024). "WWE Contacted Simon Inoki To Book Charlie Dempsey In Japan". Fightful. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ a b "AEW WrestleDream Results". All Elite Wrestling. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Miyamoto, Koji. "Antonio Inoki". Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ "Antonio Inoki leaves behind a complicated, dual legacy - Slam Wrestling". 2 October 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "Deadspin | Antonio Inoki leaves behind a legacy that rivals any in combat sports". deadspin.com. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Inoki, famed combat sports trailblazer, dies at 79". ESPN.com. 1 October 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "Combat sports world reflects on the life of Antonio Inoki, an MMA pioneer famous for first-of-its kind fight vs. Muhammad Ali | Sporting News Canada". www.sportingnews.com. 3 October 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ a b Hall, Nick (29 April 2020). "Collision in Korea: Pyongyang's historic socialism and spandex spectacular". NK News. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ Sujitaro Tamabukuro (2017). 疾風怒涛!! プロレス取調室(毎日新聞出版): UWF&PRIDE格闘ロマン編. PHP.

- ^ Antonio Inoki Home Page Archived May 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Twc-wrestle.com. Retrieved on May 10, 2014.

- ^ Sakurai, Yasuo (2010). G-Spirits - Antonio Inoki. Tatsumi Publishing. ISBN 978-4800271235.

- ^ Teruo Takahashi, Ryūketsu no majutsu saikyō no engi subete no puroresu wa shōdearu, 2001

- ^ "Great Antonio vs. Antonio Inoki – A Match That Almost Proved Deadly". prowrestlingstories.com. 9 December 2020. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "Revival of Bholu Brothers' legacy". Dawn News. 25 March 2014. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ a b Umar, Suhail Yusuf | Muhammad (25 March 2014). "Revival of Bholu Brothers' legacy". DAWN.COM. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ "Antonio Inoki WWF Champion - The Title Reign WWE Refuse to Acknowledge". Atletifo Sports. 23 August 2021. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Woodward, Hamish (23 November 2023). "Antonio Inoki Last Match Was Against Either Renzo Gracie Or Tatsumi Fujinami - Atletifo". Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ "Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye 2001". Cagematch. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Inoki Bom-Ba-Ye 2003 藤波辰爾引退セレモニー 「アントニオ猪木vs藤波辰爾 エキシビションマッチ」". YouTube. 31 December 2003. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Yuke's Media Creations". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2010.. uk.games.ign.com

- ^ Yuke's Buys Controlling Share of New Japan Pro-Wrestling Archived November 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Gamasutra.com (November 15, 2005). Retrieved on May 10, 2014.

- ^ "Zero1: "Yasukuni Shrine 150th Anniversary" Antonio Inoki invitado especial | Superluchas". 6 November 2019. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ a b Thompson, Andrew (26 August 2022). "Antonio Inoki bringing back 'IGF' as a management company called 'Inoki Genki Factory'". POST Wrestling. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Biography of Antonio Inoki". Inoki Genki Factory. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ a b Leiby, Richard. "Wrestling, anyone? Pakistan welcomes back a flamboyant Japanese hero of the ring". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ "Iraq to Free 36 Japanese Hostages". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ a b "アントニオ猪木が出馬「日本に元気を」 政界再進出の決め技は独自の外交路線". Sports Navi. Yahoo!. 5 June 2013. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Yoshida, Reiji (June 6, 2013) Antonio Inoki eyes Diet return on Nippon Ishin ticket Archived June 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Japan Times

- ^ Caldwell, James (22 July 2013). "Political news: McMahons donate to Governor Christie, Linda to run for election again? Inoki wins in Japan". Pro Wrestling Torch. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ He fought Ali – now he's an MP Archived January 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Brisbanetimes.com.au (July 23, 2013). Retrieved on May 10, 2014.

- ^ Japanese wrestling legend Antonio Inoki wins seat in Upper House Archived July 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Japan Daily Press (July 22, 2013). Retrieved on May 10, 2014.

- ^ "Inoki Banned from Diet for 30 Days over N. Korea Visit". Jiji Press. Archived from the original on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "訪朝の猪木氏、金永南氏と会談 朝鮮中央通信伝える". 朝日新聞. 29 July 2013. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ "独占インタビュー アントニオ猪木「北朝鮮でオレが見たもの」". 週刊現代. 4 January 2014. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

「私はこれまで27回も訪朝して、北朝鮮国民の暮らしぶりを見てきましたから、あの国のありのままの姿を知っています。ところが日本政府は、拉致問題が明らかになって以降、完全にドアを閉ざし、日朝関係は膠着状態に陥ってしまった。誰かがメッセージを送り続けなければ、拉致問題も解決しません。手前味噌かもしれませんが、私は北朝鮮出身のプロレスラー・力道山の弟子ということで、いくらかの知名度があると思います。11月に訪朝した時には、現地で力道山の特集番組が放送され、私の写真も紹介されました。放送翌日には、多くの人から握手を求められた。そんな自分の立場を活かしたいんです」

- ^ "猪木議員 都知事選出馬あるぞ 本命候補に躍り出る?". スポーツニッポン. 3 January 2014. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ "Lawmaker Antonio Inoki to visit North Korea again this week". The Japan Times. 2 September 2017. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Jeremy Thomas (27 June 2019). "Antonio Inoki Announces Retirement From Politics". 411Mania. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Sanger, David (21 July 1989). "Japan's Opposition Tailors Itself to the Mainstream". The New York Times.

- ^ "Japanese celebrities to help promote Palau". Marianas Variety. 14 May 2002. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ "イノキアイランドの観光ガイド|アントニオ猪木オーナーの日本友好の島". Palau Times. 20 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ a b "【猪木さん死去】在パラオ日本大使館「イノキアイランドと呼ばれる島も」大使夫妻との写真掲載し追悼". Nikkan Sports. 1 October 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ USA karate story : Chuck Norris – Joe Lewis – Bill Wallace: Everett "Monster Man" Eddy Archived October 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Karate-in-english-lewis-wallace.blogspot.com. July 18, 2009.

- ^ Ortiz, Sergio (November 1975) "The Rise and Fall of Contact Karateka" Archived May 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Black Belt Magazine, Vol. 13, No. 11.

- ^ See the documentary film "Kings of the Square Ring" Archived 2017-02-09 at the Wayback Machine for excerpts

- ^ Full bout available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0B1mugcGO4 Archived 2016-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [1] Archived March 29, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Cohen, Eric. Antonio Inoki vs Muhammad Ali Archived November 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, About.com, Retrieved on December 1, 2007.

- ^ "Inoki vs. Ali Footage". YouTube. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ^ Tallent, Aaron (20 February 2005). "The Joke That Almost Ended Ali's Career". Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "Total Attendance".

- ^ a b Black Belt. Active Interest Media, Inc. January 2003.

- ^ "February 2003 News Archive". Ichiban Puroresu. February 2003. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ Alonso, Marcelo (16 April 2005). "Wallid confirms Jungle Fight 4". ADCC Submission Fighting World Championship. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

Wallid Ismail, co-promoter of the Jungle Fight in conjunction with main promoter Antonio Inoki, has just released the list of fighters for Jungle Fight 4, Road to Las Vegas.

- ^ Izumikawa, Carol (12 September 2020). "Being Related to Mr. Miyagi". Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Mestre Juichi Sagara". Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ "ESCUELA SHOTOKAN MALDONADO - KARATE-DO URUGUAY". Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ 猪木の実兄・快守さん死去 『デイリースポーツ』(Web版) 2011年3月26日付記事。2011年3月28日閲覧

- ^ a b c d e "猪木さん 生涯4度結婚 恋多き男の"寂しがり屋"な素顔". Sponichi Annex. 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "猪木さん、スポーツを通じた国際平和 独自外交で切り開いた道". 4 October 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ .アントニオ猪木は"戦友"倍賞美津子(2) Archived June 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. ZAKZAK (October 30, 2004). Retrieved on May 10, 2014.

- ^ "アントニオ猪木の息子 コロンビア大学に合格". J-CASTニュース. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ "[追悼秘話]アントニオ猪木を「縛った女」". 15 October 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "4度目の結婚も発覚! アントニオ猪木や川越シェフ…実はバツ2以上の芸能人4人". Excite News. 3 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "8月27日未明、妻・田鶴子が永眠致しました。 生前のご厚誼に深く感謝致します。カメラマンとして私の写真を撮りながら、いつも献身的に尽くしてくれました。 今は感謝の言葉しかありません。故人の遺志により、葬儀は家族葬で行います。弔問、香典、供花はご辞退申し上げます。アントニオ猪木". Antonio Inoki on Twitter. 27 August 2019. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ "Hirota "Hiro" Inoki". Santa Monica College. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Congratulations to Hirota Inoki, a member of the ESHS swim team, who beat the school record last week in the 100-yard freestyle with a time of 42.69! With this amazing accomplishment, he qualifies for the City Section Division Championships. 🏊♂️". El Segundo High School on Facebook. 6 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "アントニオ猪木さん、孫の寛太氏がIGF役員就任…海外ネットワーク部門担当". スポーツ報知. 8 June 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ Lee, Joseph (19 January 2024). "Katsuyori Shibata Reportedly Training Antonio Inoki's Grandson". 411 Mania. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "WWE Hall Of Fame Antonio Inoki Grandson Naoto Inoki Training!! #inokidojo #strongstyle #puroresu #ichiban #ichibaaaan". Inoki Dojo on Facebook. 21 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Naoto Inoki on Instagram Archived April 11, 2024, at the Wayback Machine. Instagram.com (April 11, 2024). Retrieved on April 11, 2024.

- ^ "Naoto Inoki (w/ Durango Kid) vs Casanova for Backyard Squabbles (07-20-24)". Lucha Wrestling Puroresu on YouTube. 21 July 2024. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ Hanaoka, Mimi (22 July 2014). "Wrestler, Statesman, Hostage Negotiator, Legend: The Life of Antonio Inoki". Grantland. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ Seeto, Damian (22 December 2012). "Antonio Inoki Embraces and Accepts The Nation Of Islam". Rantsports.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2014..

- ^ "Legendary Japanese wrestler Muhammad Hussain Inoki revisits Pakistan on a Peace Festival". Pakistan Explorer. 12 July 2012. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Mosbergen, Dominique (31 January 2013). "Antonio Inoki, Wrestling Legend, Converts To Islam, Promotes International Peace (video)". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ "Antonio Inoki Sakabar - Shinjuku". Taiken Japan. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ Podgorski, Alex (2 October 2022). "Antonio Inoki leaves behind a complicated, dual legacy". Slam Wrestling. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ アントニオ猪木さん 自宅で死去 79歳 燃える闘魂 プロレス黄金期けん引. Yahoo! Japan (in Japanese). 1 October 2022. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Rose, Bryan (1 October 2022). "Antonio Inoki passes away at 79 years old". Wrestling Observer Newsletter. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Wells, Adam (1 October 2022). "WWE Hall of Famer Antonio Inoki Dies at Age 79". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "新日本プロレスロンドン大会でアントニオ猪木さん追悼…オカダ・カズチカと棚橋弘至がリングに並びテンカウント". 2 October 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "【DeNA】プロレスファンの三浦監督、猪木さん死去を悼む「すごく大きな方でオーラがあって」". Nikkan Sports. 1 October 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "【DeNA】アントニオ猪木さんを追悼 横浜スタジアムに「炎のファイター」流れる". Tokyo Sports. 1 October 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "NJPW planned to announce Antonio Inoki as their Honorary Chairman for life". POST Wrestling. 2 October 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "NJPW pays Inoki tribute, Memorial Wrestle Kingdom set 【WK17】". New Japan Pro-Wrestling. 10 October 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Thompson, Andrew (1 November 2022). "INOKI BOM-BA-YE x Ganryujima scheduled for 12/28 at Ryōgoku Sumo Hall". POST Wrestling. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ "【RIZIN】最後に響いたアントニオ猪木さんの「1、2、3、ダーッ!」 高田延彦が絶叫締め". ECOUNT. 31 December 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Currier, Joseph (10 October 2022). "NJPW dedicating Wrestle Kingdom 17 to Antonio Inoki, main event set". Wrestling Observer Newsletter. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "All Together Again live results: NJPW/AJPW/NOAH crossover". 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d "アントニオ猪木さん 日本レスラー初「従四位」「旭日中綬章」授与 伝達の1・23には特別な意味". Tokyo Sports. 16 January 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "10月1日は「闘魂アントニオ猪木の日」 日本記念日協会が認定". 13 June 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "猪木さんの一周忌法要 燃える闘魂ブロンズ像の前で「ダァー!!」". 13 September 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Carey, Ian (27 August 2023). "Tony Khan announces AEW WrestleDream PPV, Full Gear date & location". Wrestling Observer Figure Four Online. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ Lambert, Jeremy (11 April 2024). "AEW Announces Dates And Locations For 2024 PPV Events". Fightful. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "NJPW set for Inoki memorial event in Shanghai!". New Japan Pro-Wrestling. 17 September 2024. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bryant, Steve (18 April 2019). "Lucha Otaku and Inoki Sports Management partner to launch PuroLucha". SoCal Uncensored. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Toole, Mike (23 December 2018). "The Mike Toole Show - To Hell and Baki". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Int'l film festival begins in N. Korea, playing Japan's 'Acacia'". Kyodo News. 20 September 2010.

- ^ Harris, Jeffrey (20 May 2021). "New Clips for Tonight's 'The Collision in Korea' Episode of Dark Side of the Ring". 411 Mania. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "アントニオ猪木さん、没後1年 壮大な軌跡を追ったドキュメンタリー映画、10月6日公開". 映画.com. 12 July 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Entourage « Antonio Inoki « Wrestlers Database « CAGEMATCH - The Internet Wrestling Database". www.cagematch.net. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "INOKI DOJO USA FIGHTERS". New Japan Pro-Wrestling. Archived from the original on 29 March 2006. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Thank You Mr. Inoki Because Of You I Found My Path To Chase My Dream And I Will Forever Be Grateful!! You Will Forever Be #1 ICHIBAAAAANNN!!!!! 💯👊💥 RIP Mr. Inoki 2007 East Los Angeles 17 Year Old Laberinto Antonio Inoki Durango Kid". Labyrinth Laberinto on Facebook. 1 October 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Pacific Pro Wrestling - Hartley Jackson". pacificprowrestling.com. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Antonio Inoki Stats and Profile". eWrestlingNews.com. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Prowrestling Album 2 - Antonio Inoki's Martial Arts World Finals, Baseball Magazine, October 1986

- ^ Rasool, Noman (27 January 2024). "Josh Barnett Reflects on Wrestling's Enduring Wisdom". Wrestling World. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

Josh Barnett initially made his wrestling debut in 2003 with New Japan Pro Wrestling after rigorous training under the guidance of Antonio Inoki.

- ^ "Ricky Reyes". Online World of Wrestling. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Pope, Kristian (2005). "Hashimikov, Salman (1980s–1990s)". Tuff Stuff - Professional wrestling field guide. Iola, Wisconsin: KP Books. p. 218. ISBN 0-89689-267-0.

- ^ "Actress, female wrestler and Glamour model Desire". Koffin Kitten. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007.

- ^ "Tiger Ali Singh ready to take on the world". Canoe.com. Postmedia Network. 1997. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "T.J. Perkins". Online World of Wrestling. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ "Induction Weekend 2022". Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Japan Cup Elimination Tag League « Tournaments Database « CAGEMATCH – The Internet Wrestling Database Archived June 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Cagematch.net. Retrieved on May 10, 2014.

- ^ NJPW Greatest Wrestlers Archived August 23, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. New Japan Pro-Wrestling. Retrieved on August 23, 2014.

- ^ Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2000). "Texas: NWA World Tag Team Title [Siegel, Boesch and McLemore]". Wrestling title histories: professional wrestling champions around the world from the 19th century to the present. Pennsylvania: Archeus Communications. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ "National Wrestling Alliance World Tag Team Title [E. Texas]". Wrestling-Titles. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Dave. "Multi-Promotional Supercard! World Wrestling Peace Festival Unites The World!." Pro Wrestling Illustrated. Fort Washington, Pennsylvania: London Publishing Company. (November 1996): pg. 26–29.

- ^ "AJ Styles y Becky Lynch lideran los premios PWI 2018". Súper Luchas (in Spanish). 11 January 2019. Archived from the original on 12 January 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Pedicino, Joe; Solie, Gordon (hosts) (13 June 1987). "Pro Wrestling This Week". Superstars of Wrestling. Atlanta, Georgia. Syndicated. WATL.

- ^ 東京スポーツ プロレス大賞. Tokyo Sports (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ 東京スポーツ プロレス大賞. Tokyo Sports (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f 東京スポーツ プロレス大賞. Tokyo Sports (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g 東京スポーツ プロレス大賞. Tokyo Sports (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ 【プロレス大賞】宮原健斗 3度目の殊勲賞で全日本50周年に華「51年目もさらに盛り上げていく」. Tokyo Sports (in Japanese). 16 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Centinela, Teddy (13 April 2015). "En un día como hoy... 1980: Cartel súper internacional en El Toreo: Antonio Inoki vs. Tiger Jeet Singh — Fishman vs. Tatsumi Fujinami". SuperLuchas Magazine (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "NAOKI OTSUKA AND THE EARLY YEARS OF NJPW, #9: THE LION AND THE DRAGON". 20 February 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Joyce, Andrew (12 October 2010). "Antonio Inoki: Wrestling North Korea to Diplomacy?". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Antonio Inoki – Friend of North Korea". Japan Probe. 22 September 2010. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "アントニオ猪木氏、キューバから「友好勲章」". Sankei Sports. 20 November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Antonio Inoki on Twitter

- Antonio Inoki on YouTube

- Antonio Inoki on WWE.com

- Antonio Inoki's English Home Page

- House of Councillor profile: Mr. Antonio Inoki Archived July 22, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Puroresu.com profile: Antonio Inoki

- National Wrestling Hall of Fame profile: Antonio Inoki

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame profile: Antonio Inoki Archived May 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Antonio Inoki's profile at Cagematch.net , Wrestlingdata.com , Internet Wrestling Database

- Article on the Kansui-ryū karate style created by Antonio Inoki and Yukio Mizutani Archived January 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- 1943 births

- 2022 deaths

- Converts to Shia Islam

- Deaths from amyloidosis

- Heavyweight mixed martial artists

- Mixed martial artists utilizing karate

- Mixed martial artists utilizing wrestling

- Mixed martial artists utilizing catch wrestling

- Mixed martial artists utilizing shoot wrestling

- IWGP Heavyweight champions

- Japanese Buddhists

- Syncretists

- Japanese male karateka

- Japanese catch wrestlers

- Japanese emigrants to Brazil

- Japanese expatriates in the United States

- Japanese male mixed martial artists

- Japanese male professional wrestlers

- Japanese Shia Muslims

- Japanese sportsperson-politicians

- Japan Restoration Party politicians

- Martial arts school founders

- Members of the House of Councillors (Japan)

- New Japan Pro-Wrestling

- Party for Japanese Kokoro politicians

- Political party founders

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum

- Professional wrestling promoters

- Professional wrestlers who competed in MMA

- Japanese professional wrestling trainers

- Sportspeople from Tokyo

- Sportspeople from Yokohama

- WWE Hall of Fame inductees

- Stampede Wrestling alumni

- All Asia Tag Team Champions

- UWA World Heavyweight Champions

- NWF Heavyweight Champions

- NWA North American Tag Team Champions (Los Angeles/Japan version)

- NWA United National Champions

- 20th-century male professional wrestlers

- 20th-century Japanese professional wrestlers

- 20th-century Japanese politicians

- 21st-century Japanese politicians

- NWA International Tag Team Champions

- World Tag League (NJPW) winners

- G1 Climax winners

- NWA Texas Heavyweight Champions

- NWA World Tag Team Champions (Texas version)

- 20th-century Japanese sportsmen