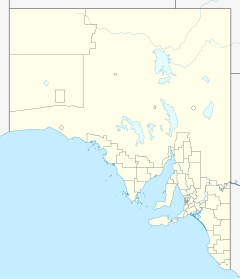

Kalamurina Sanctuary

27°55′00″S 137°59′00″E / 27.9167°S 137.9833°E

Kalamurina Sanctuary is a nature reserve in arid north-eastern South Australia. The land was established as a sheep station sometime before 1994 and then a cattle station until the early 2000s, called Kalamurina Station. It occupies 6,700 square kilometres (2,587 sq mi).

It was acquired in December 2007 by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) to become a nature reserve for biodiversity conservation and wildlife management. There are several threatened species in the sanctuary.

Landscape

[edit]Kalamurina borders on the north coast of Lake Eyre North and contains a large proportion of the Lake Eyre catchment. Its habitats include dunefields, gibber plains, desert woodlands, freshwater and saline lakes, and riparian habitats along the three important desert waterways that converge on the property[1] the Warburton and Macumba Rivers and Kallakoopah Creek.[2]

Although bordered by Cowarie Station to the east,[3] the reserve is also between the Simpson Desert Regional Reserve to the north, Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre National Park to the south, the establishment of Kalamurina as a nature reserve creates a continuous protected area in central Australia larger than the State of Tasmania.[2]

Wildlife

[edit]Since its acquisition in December 2007 by the AWC to become a nature reserve for biodiversity conservation and wildlife management, a high priority management need is to have a feral animal control program.[2]

Threatened wildlife species on Kalamurina include the crest-tailed mulgara, kultarr, Lake Eyre dragon, and Eyrean grasswren.[2] The night parrot has been reported as being sighted on the property, but the work produced by naturalist and wildlife cinematographer John Young was later found to be suspect, and reports published by the AWC were retracted.[4]

Station history

[edit]The pastoral lease for Kalamurina was established prior to 1884; at this time the property was stocked with merino sheep for the purpose of producing wool.[5] Owned in 1888 by A. Mercer, the station had also introduced camels for the transportation of supplies.[6] By 1889 a herd of cattle was being run at the property, then owned by Cave and Robertson.[7] The station had been acquired by William Robertson in about 1895.[8] A poor season was reported in 1897 with others following, resulting in Kalamurina being abandoned in 1899 as a result of drought conditions, with all the waterholes having dried up completely by 1902.[9] Robertson was declared insolvent in late 1902,[8] and the property was valued shortly afterwards at £12,675.[10] Drought hit the area again in 1908 resulting in virtually no feed left on many properties in the area, including Kalamurina, which had an area of 3,000 square miles (7,770 km2) and was stocked with about 6,000 head of cattle.[11]

In 1994, when much of the area was again in the grip of a severe drought, the station was acquired by Tony Boyd, John Said, Graeme Croft, Vince Conte and Thomas Ng, who were advised by climatologists that rains would arrive in the next season. Rains arrived and the 6,500-square-kilometre (2,510 sq mi) property had two good seasons back to back, with 3,500 cattle being reared on the property. Boyd, Said, Croft, Conte and Ng sold the station in 2003/2004.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ Misty Herrin. "Adapting to Climate Change – Kalamurina: Australia's Vast Desert Oasis". The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d AWC: Kalamurina Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Outback South Australia" (PDF). Government of South Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ Jones, Ann; Sveen, Benjamin; Lewis, David (22 March 2019). "Night parrot research labelled 'fake news' by experts after release of damning report". ABC News (Background Briefing). Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Adelaide Produce Report". Adelaide Observer. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 12 January 1884. p. 29. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ "Advertising". South Australian Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 13 December 1888. p. 8. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ "Stock Market". Adelaide Observer. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 10 August 1889. p. 21. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ a b "An Insolvent Pastoralist". The Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 28 May 1902. p. 4. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ "Geological Expedition". The Advertiser. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 25 January 1902. p. 9. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ "Insolvency Court". The Chronicle. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 31 May 1902. p. 31. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ "Feed for starving stock". The Chronicle. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 16 May 1908. p. 12. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ "Beating the odds to buy a large hunk of Oz". Pandora. 1 August 1999. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2014.