Judea

Judea

יְהוּדָה | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Coordinates: 31°40′N 35°00′E / 31.667°N 35.000°E | |

| Location | Southern Levant |

| Part of | |

| Native name | יְהוּדָה |

| Highest elevation | 1,020 m or 3,350 ft |

Judea or Judaea (/dʒuːˈdiːə, dʒuːˈdeɪə/;[1] Hebrew: יהודה, Modern: Yəhūda, Tiberian: Yehūḏā; Greek: Ἰουδαία, Ioudaía; Latin: Iudaea) is a mountainous region of the Levant. Traditionally dominated by the city of Jerusalem, it is now part of Palestine and Israel. The name's usage is historic, having been used in antiquity and still into the present day; it originates from Yehudah, a Hebrew name. Yehudah was a son of Jacob, who was later given the name "Israel" and whose sons collectively headed the Twelve Tribes of Israel. Yehudah's progeny among the Israelites formed the Tribe of Judah, with whom the Kingdom of Judah is associated. Related nomenclature continued to be used under the rule of the Babylonians (the Yehud province), the Persians (the Yehud province), the Greeks (the Hasmonean Kingdom), and the Romans (the Herodian Kingdom and the Judaea province).[2] Under the Hasmoneans, the Herodians, and the Romans, the term was applied to an area larger than Judea of earlier periods. In 132 CE, the Roman province of Judaea was merged with Galilee to form the enlarged province of Syria Palaestina.[3][4][5]

The term Judea was used by English speakers for the hilly internal part of Mandatory Palestine until the Jordanian rule of the area in 1948.[6][7] Most of the region of Judea was incorporated into what the Jordanians called ad-difa'a al-gharbiya (translated into English as the "West Bank"),[8] though "Yehuda" is the Hebrew term used for the area in modern Israel since the region was captured and occupied by Israel in 1967.[9] The Israeli government in the 20th century used the term Judea as part of the Israeli administrative district name "Judea and Samaria Area" for the territory that is generally referred to as the West Bank.[10]

Etymology

The name Judea is a Greek and Roman adaptation of the name "Judah", which originally encompassed the territory of the Israelite tribe of that name and later of the ancient Kingdom of Judah. Nimrud Tablet K.3751, dated c. 733 BCE, is the earliest known record of the name Judah (written in Assyrian cuneiform as Yaudaya or KUR.ia-ú-da-a-a).

Judea was sometimes used as the name for the entire region, including parts beyond the river Jordan.[11] In 200 CE Sextus Julius Africanus, cited by Eusebius (Church History 1.7.14), described "Nazara" (Nazareth) as a village in Judea.[12] The King James Version of the Bible refers to the region as "Jewry".[13]

"Judea" was a name used by English speakers for the hilly internal part of Mandatory Palestine until the Jordanian rule of the area in 1948. For example, the borders of the two states to be established according to the UN's 1947 partition scheme[6] were officially described using the terms "Judea" and "Samaria" and in its reports to the League of Nations Mandatory Committee, as in 1937, the geographical terms employed were "Samaria and Judea".[7] Jordan called the area ad-difa'a al-gharbiya (translated into English as the "West Bank").[8] "Yehuda" is the Hebrew term used for the area in modern Israel since the region was captured and occupied by Israel in 1967.[9]

Historical boundaries

Roman-era definition

The first century Roman-Jewish historian Josephus wrote (The Jewish War 3.3.5):

In the limits of Samaria and Judea lies the village Anuath, which is also named Borceos.[14] This is the northern boundary of Judea. The southern parts of Judea, if they be measured lengthways, are bounded by a village adjoining to the confines of Arabia; the Jews that dwell there call it Jordan. However, its breadth is extended from the river Jordan to Joppa. The city Jerusalem is situated in the very middle; on which account some have, with sagacity enough, called that city the Navel of the country. Nor indeed is Judea destitute of such delights as come from the sea, since its maritime places extend as far as Ptolemais: it was parted into eleven portions, of which the royal city Jerusalem was the supreme, and presided over all the neighboring country, as the head does over the body. As to the other cities that were inferior to it, they presided over their several toparchies; Gophna was the second of those cities, and next to that Acrabatta, after them Thamna, and Lydda, and Emmaus, and Pella, and Idumea, and Engaddi, and Herodium, and Jericho; and after them came Jamnia and Joppa, as presiding over the neighboring people; and besides these there was the region of Gamala, and Gaulonitis, and Batanea, and Trachonitis, which are also parts of the kingdom of Agrippa. This [last] country begins at Mount Libanus, and the fountains of Jordan, and reaches breadthways to Lake Tiberias; and in length is extended from a village called Arpha, as far as Julias. Its inhabitants are a mixture of Jews and Syrians. And thus have I, with all possible brevity, described the country of Judea, and those that lie round about it.[15]

Elsewhere, Josephus wrote that "Arabia is a country that borders on Judea."[16]

Geography

Judea is a mountainous region, part of which is considered a desert. It varies greatly in height, rising to an altitude of 1,020 metres (3,350 ft) in the south at the Hebron Hills, 30 km (19 mi) southwest of Jerusalem, and descending to as much as 400 metres (1,300 ft) below sea level in the east of the region. It also varies in rainfall, starting with about 400–500 millimetres (16–20 in) in the western hills, rising to 600 millimetres (24 in) around western Jerusalem (in central Judea), falling back to 400 millimetres (16 in) in eastern Jerusalem and dropping to around 100 millimetres (3.9 in) in the eastern parts, due to a rain shadow: this is the Judaean Desert. The climate, accordingly, moves between Mediterranean in the west and desert climate in the east, with a strip of semi-arid climate in the middle. Major urban areas in the region include Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Gush Etzion, Jericho and Hebron.[17]

Geographers divide Judea into several regions: the Hebron hills, the Jerusalem saddle, the Bethel hills and the Judaean Desert east of Jerusalem, which descends in a series of steps to the Dead Sea. The hills are distinct for their anticline structure. In ancient times the hills were forested, and the Bible records agriculture and sheep farming being practiced in the area. Animals are still grazed today, with shepherds moving them between the low ground to the hilltops as summer approaches, while the slopes are still layered with centuries-old stone terracing. The Jewish Revolt against the Romans ended in the devastation of vast areas of the Judean countryside.[18]

Mount Hazor marks the geographical boundary between Samaria to its north and Judea to its south.

Narrative of the biblical patriarchs

Judea is central to much of the narrative of the Torah, with the Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob said to have been buried at Hebron in the Tomb of the Patriarchs.[citation needed]

History

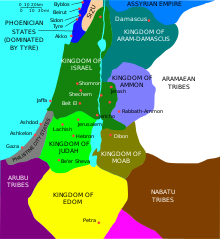

Israel and Judah, Assyrian and Babylonian periods

The early history of Judah is uncertain; the biblical account states that the Kingdom of Judah, along with the Kingdom of Israel, was a successor to a united monarchy of Israel and Judah, but modern scholarship generally holds that the united monarchy is ahistorical.[19][20][21][22] Regardless, the Northern Kingdom was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 720 BCE. The Kingdom of Judah remained nominally independent, but paid tribute to the Assyrian Empire from 715 and throughout the first half of the 7th century BCE, regaining its independence as the Assyrian Empire declined after 640 BCE, but after 609 again fell under the sway of imperial rule, this time paying tribute at first to the Egyptians and after 601 BCE to the Neo-Babylonian Empire, until 586 BCE, when it was finally conquered by Babylonia.

Persian and Hellenistic periods

The Babylonian Empire fell to the conquests of Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE.[23] Judea remained under Persian rule until the conquest of Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, eventually falling under the rule of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire until the revolt of Judas Maccabeus resulted in the Hasmonean dynasty of kings who ruled in Judea for over a century.[24]

Early Roman period

Judea lost its independence to the Romans in the 1st century BCE, becoming first a tributary kingdom, then a province, of the Roman Empire. The Romans had allied themselves to the Maccabees and interfered again in 63 BCE, at the end of the Third Mithridatic War, when the proconsul Pompey ("Pompey the Great") stayed behind to make the area secure for Rome, including his siege of Jerusalem in 63 BCE. Queen Salome Alexandra had recently died, and a civil war broke out between her sons, Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II. Pompeius restored Hyrcanus but political rule passed to the Herodian dynasty, who ruled as client kings.

In 6 CE, Judea came under direct Roman rule as the southern part of the province of Judaea, although Jews living there still maintained some form of independence and could judge offenders by their own laws, including capital offences, until c. 28 CE.[25] The province of Judea, during the late Hellenistic period and early Roman Empire was also divided into five conclaves: Jerusalem, Gadara, Amathus, Jericho, and Sepphoris,[26] and during the Roman period had eleven administrative districts (toparchies): Jerusalem, Gophna, Akrabatta, Thamna, Lod, Emmaus, Pella, Idumaea, Ein Gedi, Herodeion, and Jericho.[27]

Jewish–Roman wars and Late Roman period

First Jewish–Roman War

In 66 CE, the Jewish population rose against Roman rule in a revolt that was unsuccessful. Jerusalem was besieged in 70 CE. The city was razed, the Second Temple was destroyed, and much of the population was killed or enslaved.[28]

Bar Kokhba revolt

In 132 CE, the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE) broke out. After an initial string of victories, rebel leader Simeon Bar Kokhba was able to form an independent Jewish state that lasted several years and included most of the district of Judea, including the Judean Mountains, the Judean Desert, and northern Negev desert, but probably not other sections of the country.

Aftermath

When the Romans finally put an end to the uprising, most of the Jews in Judea were killed or displaced, and a sizable number of captives were sold into slavery, leaving the district mostly depopulated. Jews were expelled from the area surrounding Jerusalem.[29][30][31] No village in the district of Judea whose remains have been excavated so far has not been destroyed during the revolt.[32] Roman emperor Hadrian, determined to root out Jewish nationalism, changed the name of the province from Judaea to Syria Palaestina.[33] The province's Jewish population was now mainly concentrated in Galilee, the coastal plain (especially in Lydda, Joppa, and Caesarea), and smaller Jewish communities continued to live in the Beth She'an Valley, the Carmel, and Judea's northern and southern frontiers, including the southern Hebron Hills and along the shores of the Dead Sea.[34][35]

The suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt led to widespread destruction and displacement throughout Judea, and the district saw a decline in population. The Roman colony of Aelia Capitolina, which was built on the ruins of Jerusalem, remained a backwater for the duration of its existence.[30] The villages around the city were depopulated, and arable lands in the region were confiscated by the Romans. Having no alternative population to fill the empty villages led the authorities to establish imperial or legionary estates and monasteries on confiscated village lands to benefit the elites and, later, the church.[36] This also initiated a process of romanization that took place during the Late Roman period, with pagan populations penetrating the region and settling alongside Roman veterans.[37][29] There was only a revival of village settlement on the eastern edges of Jerusalem's hinterland, on the transition between the arable highlands and the Judaean Desert. Those settlements grew on marginal lands with vague ownership and unenforced state land dominion.[36]

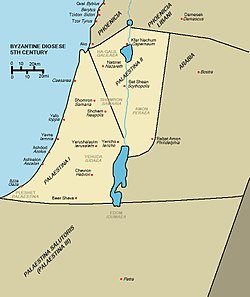

Byzantine period

Judea's decline only came to an end in the fifth century CE, when it developed into a monastic center, and Jerusalem became a major Christian pilgrimage and ecclesiastical hub.[30] Under Byzantine rule, the regional population, composed of pagan populations who had migrated there after Jews were driven out following the Bar Kokhba revolt, gradually converted to Christianity.[29]

The Byzantines redrew the borders of the land of Palestine. The various Roman provinces (Syria Palaestina, Samaria, Galilee, and Peraea) were reorganized into three dioceses of Palaestina, reverting to the name first used by Greek historian Herodotus in the mid-5th century BCE: Palaestina Prima, Secunda, and Tertia or Salutaris (First, Second, and Third Palestine), part of the Diocese of the East.[38][39] Palaestina Prima consisted of Judea, Samaria, the Paralia, and Peraea with the governor residing in Caesarea. Palaestina Secunda consisted of Galilee, the lower Jezreel Valley, the regions east of Galilee, and the western part of the former Decapolis with the seat of government at Scythopolis. Palaestina Tertia included the Negev, southern Jordan—once part of Arabia—and most of Sinai, with Petra as the usual residence of the governor. Palestina Tertia was also known as Palaestina Salutaris.[38][40] According to historian H.H. Ben-Sasson,[41] this reorganisation took place under Diocletian (284–305), although other scholars suggest this change occurred later, in 390.

Crusader period

According to Ellenblum, the Franks tended to settle in the southern half of the region between Jerusalem and Nablus since there was a sizable Christian population there.[42][43]

Mamluk period

Most of the people living in the northern portion of Judea in the late 16th century were Muslims; some of them resided in towns that today have significant Christian populations. According to the 1596–1597 Ottoman census, Birzeit and Jifna, for instance, were wholly Muslim villages, while Taybeh had 63 Muslim families and 23 Christian families. There were 71 Christian families and 9 Muslim families in Ramallah, although the Christians there were recent arrivals who had moved from the Kerak area only a few years previously. According to Ehrlich, the region's Christian population decreased as a result of a combination of factors including impoverishment, oppression, marginalization, and persecution. Sufi activity took place in Jerusalem and the surrounding area, which most likely pushed Christian villagers in the region to convert to Islam.[43]

Timeline

- Around 900–586 BCE: Kingdom of Judah

- 586–539 BCE: Yehud, Babylonian Empire

- 539–332 BCE: Yehud Medinata, Persian Empire

- 332–305 BCE: Macedonian Empire of Alexander the Great

- 305–198 BCE: Ptolemaic Egypt

- 198–141 BCE: Seleucid Empire

- 141–37 BCE: The Hasmonean kingdom established by the Maccabees, under the Roman Empire after 63 BCE

- 63 BCE: Pompey's conquest of Jerusalem

- 37 BCE – 132 CE: Herodian dynasty ruling Judea as a vassal state of the Roman Empire (37–4 BCE Herod the Great, 4 BCE – 6 CE Herod Archelaus, 41–44 CE Agrippa I), interchanging with direct Roman rule (6–41, 44–132)

- c. 25 BCE: Caesarea Maritima is built by Herod the Great, replacing Jerusalem as the capital

- 6 CE the Roman Empire deposed Herod Archelaus and converted his territory into the Roman province of Judea.

- Census of Quirinius, too late to correspond to census related to Jesus' birth

- 26–36: Pontius Pilate prefect of Roman Judea during the Crucifixion of Jesus

- 66–73: First Jewish–Roman War, includes Destruction of the Second Temple in 70

- 115–117: Kitos War

- 132: Judea was merged with Galilee into the enlarged province of Syria Palaestina.[4][5]

Selected towns and cities

Judea, in the generic sense, also incorporates places in Galilee and in Samaria.

| English | Hebrew (Masoretic, 7th–10th century CE) | Greek (Josephus, LXX, 3rd century BCE – 1st century CE) | Latin | Arabic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jerusalem | ירושלם | Ιερουσαλήμ | Herusalem (Aelia Capitolina) | القدس (al-Quds) |

| Jericho | יריחו | Ίεριχω | Hiericho / Herichonte | أريحا (Ariḥa) |

| Shechem / Nablus | שכם | Νεάπολις (Neapolis) |

Neapoli | نابلس (Nablus) |

| Jaffa | יפו | Ἰόππῃ | Ioppe | يَافَا (Yaffa) |

| Ascalon | אשקלון | Ἀσκάλων (Askálōn) | Ascalone | عَسْقَلَان (Asqalān) |

| Beit Shean | בית שאן | Σκυθόπολις (Scythopolis) Βαιθσάν (Beithsan) |

Scytopoli | بيسان (Beisan) |

| Beth Gubrin /Maresha | בית גוברין | Ἐλευθερόπολις (Eleutheropolis) |

Betogabri | بيت جبرين (Bayt Jibrin) |

| Kefar Othnai | (לגיון) כפר עותנאי | xxx | Caporcotani (Legio) | اللجّون (al-Lajjûn) |

| Peki'in | פקיעין | Βακὰ[44] | xxx | البقيعة (al-Buqei'a) |

| Jamnia | יבנה | Ιαμνεία | Iamnia | يبنى (Yibna) |

| Samaria / Sebaste | שומרון / סבסטי | Σαμάρεια / Σεβαστή | Sebaste | سبسطية (Sabastiyah) |

| Paneas / Caesarea Philippi | פנייס | Πάνειον (Καισαρεία Φιλίππεια) (Paneion) |

Cesareapaneas | بانياس (Banias) |

| Acre / Ptolemais | עכו | Πτολεμαΐς (Ptolemais) Ἀκχώ (Akchó) |

Ptoloma | عكّا (ʻAkka) |

| Emmaus | אמאוס | Ἀμμαοῦς (Νικορολις) (Nicopolis) |

Nicopoli | عمواس ('Imwas) |

See also

- Timeline of the name Judea

- Seleucid Empire versus Maccabean Revolt

- History of Palestine

- Ioudaios

- Kitos War

- Judaea (Roman province)

- State of Judea

References

- ^ "Definition of Judaea in English". Lexico Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Crotty, Robert Brian (2017). The Christian Survivor: How Roman Christianity Defeated Its Early Competitors. Springer. p. 25 f.n. 4. ISBN 9789811032141. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

The Babylonians translated the Hebrew name [Judah] into Aramaic as Yehud Medinata ('the province of Judah') or simply 'Yehud' and made it a new Babylonian province. This was inherited by the Persians. Under the Greeks, Yehud was translated as Judaea and this was taken over by the Romans. After the Jewish rebellion of 135 CE, the Romans renamed the area Syria Palaestina or simply Palestine. The area described by these land titles differed to some extent in the different periods.

- ^ Clouser, Gordon (2011). Jesus, Joshua, Yeshua of Nazareth Revised and Expanded. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4620-6121-1.

- ^ a b Spolsky, Bernard (2014). The Languages of the Jews: A Sociolinguistic History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05544-5.

- ^ a b Brand, Chad; Mitchell, Eric; Staff, Holman Reference Editorial (2015). Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8054-9935-3.

- ^ a b "A/RES/181(II) of 29 November 1947". Unispal.un.org. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Mandate for Palestine – Report of the Mandatory to the LoN (31 December 1937)". Unispal.un.org. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ a b "This Side of the River Jordan; On Language," Philologos, September 22, 2010, Forward.

- ^ a b "Judaea". Britannica. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Neil Caplan (19 September 2011). The Israel-Palestine Conflict: Contested Histories. John Wiley & Sons. p. 8. ISBN 978-1405175395.

- ^ Riggs, J. S. (1894). "Studies in Palestinian Geography. II. Judea". The Biblical World. 4 (2): 87–93. doi:10.1086/471491. ISSN 0190-3578. JSTOR 3135423. S2CID 144961794.

- ^ "A few of the careful, however, having obtained private records of their own, either by remembering the names or by getting them in some other way from the registers, pride themselves on preserving the memory of their noble extraction. Among these are those already mentioned, called Desposyni, on account of their connection with the family of the Saviour. Coming from Nazara and Cochaba, villages of Judea, into other parts of the world, they drew the aforesaid genealogy from memory and from the book of daily records as faithfully as possible." (Eusebius Pamphili, Church History, Book I, Chapter VII,§ 14)

- ^ For example at Luke 23:5 and John 7:1

- ^ Based on Charles William Wilson's (1836–1905) identification of this site, who thought that Borceos may have been a place about 18 kilometers to the south of Neapolis (Nablus) because of a name similarity (Berkit). See p. 232 in: Wilson, Charles William (1881). Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt. Vol. 1. New York: D. Appleton.. This identification is the result of the equivocal nature of Josephus' statement, where he mentions both "Samaria" and "Judea." Samaria was a sub-district of Judea. Others speculate that Borceos may have referred to the village Burqin, in northern Samaria, and which village marked the bounds of Judea to its north.

- ^ "Ancient History Sourcebook: Josephus (37 – after 93 CE): Galilee, Samaria, and Judea in the First Century CE". Fordham.edu. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities XIV.I.4. (14.14)

- ^ "Picturesque Palestine I: Jerusalem, Judah, Ephraim". Lifeintheholyland.com. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ "Unlikely A Tale of Two Conquests: The Unlikely Numismatic Association Between the Fall of New France (AD 1760) and the Fall of Judaea (AD 70)". Ansmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Kuhrt, Amiele (1995). The Ancient Near East. Routledge. p. 438. ISBN 978-0415167628.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel, and Silberman, Neil Asher, The Bible Unearthed : Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, Simon & Schuster, 2002. ISBN 0-684-86912-8

- ^ "The Bible and Interpretation – David, King of Judah (Not Israel)". bibleinterp.arizona.edu. 13 July 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Thomas L., 1999, The Bible in History: How Writers Create a Past, Jonathan Cape, London, ISBN 978-0-224-03977-2 p. 207

- ^ "Cyrus the Great | Biography & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "Palestine – The Hasmonean priest-princes". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Avodah Zarah 8b; ibid, Sanhedrin 41a

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities Book 14, chapter 5, verse 4

- ^ Schürer, E. (1891). Geschichte des jüdischen Volkes im Zeitalter Jesu Christi [A History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus Christ]. Geschichte de jüdischen Volkes im Zeitalter Jesu Christi.English. Vol. 1. Translated by Miss Taylor. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 157. Cf. Flavius Josephus, The Wars of the Jews 3:51.

- ^ "Titus' Siege of Jerusalem – Livius". www.livius.org.

- ^ a b c Bar, Doron (2005). "Rural Monasticism as a Key Element in the Christianization of Byzantine Palestine". The Harvard Theological Review. 98 (1): 49–65. doi:10.1017/S0017816005000854. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 4125284. S2CID 162644246.

The phenomenon was most prominent in Judea, and can be explained by the demographic changes that this region underwent after the second Jewish revolt of 132–135 C.E. The expulsion of Jews from the area of Jerusalem following the suppression of the revolt, in combination with the penetration of pagan populations into the same region, created the conditions for the diffusion of Christians into that area during the fifth and sixth centuries. [...] This regional population, originally pagan and during the Byzantine period gradually adopting Christianity, was one of the main reasons that the monks chose to settle there. They erected their monasteries near local villages that during this period reached their climax in size and wealth, thus providing fertile ground for the planting of new ideas.

- ^ a b c Schwartz, Seth (2006), Katz, Steven T. (ed.), "Political, social, and economic life in the Land of Israel, 66–c. 235", The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 4, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 36–37, doi:10.1017/chol9780521772488.003, ISBN 978-0-521-77248-8, retrieved 31 March 2023

- ^ Taylor, J. E. (15 November 2012). The Essenes, the Scrolls, and the Dead Sea. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199554485.

These texts, combined with the relics of those who hid in caves along the western side of the Dead Sea, tells us a great deal. What is clear from the evidence of both skeletal remains and artefacts is that the Roman assault on the Jewish population of the Dead Sea was so severe and comprehensive that no one came to retrieve precious legal documents, or bury the dead. Up until this date the Bar Kokhba documents indicate that towns, villages and ports where Jews lived were busy with industry and activity. Afterwards there is an eerie silence, and the archaeological record testifies to little Jewish presence until the Byzantine era, in En Gedi. This picture coheres with what we have already determined in Part I of this study, that the crucial date for what can only be described as genocide, and the devastation of Jews and Judaism within central Judea, was 135 CE and not, as usually assumed, 70 CE, despite the siege of Jerusalem and the Temple's destruction

- ^ Eshel, Hanan (2006). "4: The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132 – 135". In T. Katz, Steven (ed.). The Cambridge History of Judaism. Vol. 4. The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period. Cambridge: Cambridge. pp. 105–127. ISBN 9780521772488. OCLC 7672733.

- ^ Ben-Sasson, H.H. (1976). A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, page 334: "In an effort to wipe out all memory of the bond between the Jews and the land, Hadrian changed the name of the province from Iudaea to Syria-Palestina, a name that became common in non-Jewish literature."

- ^ Goodblatt, David (2006). "The political and social history of the Jewish community in the Land of Israel", in William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein, Steven T. Katz (eds.) The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, Cambridge University Press, pp. 404–430 (406).

- ^ Mor, Menahem (2016). The Second Jewish Revolt. Brill. pp. 483–484. doi:10.1163/9789004314634. ISBN 978-90-04-31463-4.

Land confiscation in Judaea was part of the suppression of the revolt policy of the Romans and punishment for the rebels. But the very claim that the sikarikon laws were annulled for settlement purposes seems to indicate that Jews continued to reside in Judaea even after the Second Revolt. There is no doubt that this area suffered the severest damage from the suppression of the revolt. Settlements in Judaea, such as Herodion and Bethar, had already been destroyed during the course of the revolt, and Jews were expelled from the districts of Gophna, Herodion, and Aqraba. However, it should not be claimed that the region of Judaea was completely destroyed. Jews continued to live in areas such as Lod (Lydda), south of the Hebron Mountain, and the coastal regions. In other areas of the Land of Israel that did not have any direct connection with the Second Revolt, no settlement changes can be identified as resulting from it.

- ^ a b Seligman, J. (2019). "Were There Villages in Jerusalem's Hinterland During the Byzantine Period?" In Peleg- Barkat O. et. al. (eds.), Between Sea and Desert: On Kings, Nomads, Cities and Monks. Essays in Honor of Joseph Patrich. Jerusalem: Tzemach. pp. 167–179.

- ^ Zissu, Boaz [in Hebrew]; Klein, Eitan (2011). "A Rock-Cut Burial Cave from the Roman Period at Beit Nattif, Judaean Foothills" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 61 (2): 196–216. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ a b Shahin (2005), p. 8

- ^ Thomas A. Idniopulos (1998). "Weathered by Miracles: A History of Palestine From Bonaparte and Muhammad Ali to Ben-Gurion and the Mufti". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ^ "Roman Arabia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ^ H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, p. 351

- ^ Ronnie, Ellenblum (2010). Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–229. ISBN 978-0-511-58534-0. OCLC 958547332.

- ^ a b Ehrlich, Michael (2022). "Judea and Jerusalem". The Islamization of the Holy Land, 634–1800. Leeds: Arc Humanities Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-1-64189-222-3. OCLC 1310046222.

- ^ Josephus, The Jewish War 3.3.1

External links

- Judea and civil war

- The subjugation of Judea Archived 2016-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Judaea 6–66 CE Archived 2015-05-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Judea photos