J. G. Ballard

J. G. Ballard | |

|---|---|

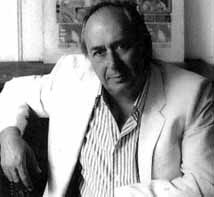

Ballard in 1984 | |

| Born | James Graham Ballard 15 November 1930 Shanghai International Settlement, Republic of China (present-day Shanghai, People's Republic of China) |

| Died | 19 April 2009 (aged 78) London, England, UK |

| Resting place | Kensal Green Cemetery |

| Occupation | Novelist, satirist, short story writer, essayist |

| Alma mater | King's College, Cambridge Queen Mary University of London[1] |

| Genre | Dystopian fiction Satire Science fiction Transgressive fiction |

| Literary movement | New Wave |

| Notable works | Crash Empire of the Sun High-Rise The Atrocity Exhibition |

| Spouse |

Helen Mary Matthews

(m. 1955; died 1964) |

| Children | 3, including Bea Ballard |

James Graham Ballard (15 November 1930 – 19 April 2009)[2] was an English novelist and short-story writer, satirist and essayist known for psychologically provocative works of fiction that explore the relations between human psychology, technology, sex and mass media.[3] Ballard first became associated with New Wave science fiction for post-apocalyptic novels such as The Drowned World (1962). He later courted controversy with the short-story collection The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), which includes the 1968 story "Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan", and later the novel Crash (1973), a story about car-crash fetishists.

In 1984, Ballard won broad critical recognition for the war novel Empire of the Sun, a semi-autobiographical story of the experiences of a British boy during the Japanese occupation of Shanghai;[4] three years later, the American film director Steven Spielberg adapted the novel into a film of the same name. The novelist's journey from youth to mid-age is chronicled, with fictional inflections, in The Kindness of Women (1991), and in the autobiography Miracles of Life (2008). Some of Ballard's early novels have been adapted as films, including Crash (1996), directed by David Cronenberg, and High-Rise (2015), an adaptation of the 1975 novel directed by Ben Wheatley.

From the distinct nature of the literary fiction of J. G. Ballard arose the adjective Ballardian, defined as: "resembling or suggestive of the conditions described in J. G. Ballard's novels and stories, especially dystopian modernity, bleak man-made landscapes, and the psychological effects of technological, social or environmental developments".[5] The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography describes the novelist Ballard as preoccupied with "Eros, Thanatos, mass media and emergent technologies".[6]

Life

[edit]Shanghai

[edit]J. G. Ballard was born to Edna Johnstone (1905–1998)[6] and James Graham Ballard (1901–1966), who was a chemist at the Calico Printers' Association, a textile company in the city of Manchester, and later became the chairman and managing director of the China Printing and Finishing Company, the Association's subsidiary company in Shanghai.[6] The China in which Ballard was born featured the Shanghai International Settlement, where Western foreigners "lived an American style of life".[7] At school age, Ballard attended the Cathedral School of the Holy Trinity Church, Shanghai.[8] Upon the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), the Ballard family abandoned their suburban house, and moved to a house in the city centre of Shanghai to avoid the warfare between the Chinese defenders and the Japanese invaders.

After the Battle of Hong Kong (8–25 December 1941), the Imperial Japanese Army occupied the International Settlement and imprisoned the Allied civilians in early 1943. The Ballard family were sent to the Lunghua Civilian Assembly Centre where they lived in G-block, a two-storey residence for 40 families, for the remainder of the Second World War. At the Lunghua Centre, Ballard attended school, where the teachers were prisoners with a profession. In the autobiography Miracles of Life, Ballard said that those experiences of displacement and imprisonment were the thematic bases of the novel Empire of the Sun.[9][10]

Concerning the violence found in Ballard's fiction,[11][12] the novelist Martin Amis said that Empire of the Sun "gives shape to what shaped him."[13] About his experiences of the Japanese war in China, Ballard said: "I don't think you can go through the experience of war without one's perceptions of the world being forever changed. The reassuring stage-set that everyday reality in the suburban West presents to us is torn down; you see the ragged scaffolding, and then you see the truth beyond that, and it can be a frightening experience."[12] "I have—I won't say happy—[but] not unpleasant memories of the camp... I remember a lot of the casual brutality and beatings-up that went on—but, at the same time, we children were playing a hundred and one games all the time!"[7] In his later life, Ballard became an atheist, yet said: "I'm extremely interested in religion ... I see religion as a key to all sorts of mysteries that surround the human consciousness."[14]

Britain and Canada

[edit]In late 1945, Ballard's mother returned to Britain with J. G. and his sister, where they resided at Plymouth, and he attended The Leys School in Cambridge,[15] where he won a prize for a well-written essay.[16] Within a few years, Mrs Ballard and her daughter returned to China and rejoined Mr Ballard; and, whilst not at school, Ballard resided with grandparents. In 1949, he studied medicine at King's College, Cambridge, with the intention of becoming a psychiatrist.[17]

At university, Ballard wrote avant-garde fiction influenced by psychoanalysis and the works of surrealist painters, and pursued writing fiction and medicine. In his second year at Cambridge, in May 1951, the short story "The Violent Noon", a Hemingway pastiche, won a crime-story competition and was published in the Varsity newspaper.[18][19] In October 1951, encouraged by publication, and understanding that clinical medicine disallowed time to write fiction, Ballard forsook medicine and enrolled at Queen Mary College to read English literature.[20] After a year, he quit the College and worked as an advertising copywriter,[21] then worked as an itinerant encyclopaedia salesman.[22] Throughout that odd-job period, Ballard continued writing short-story fiction but found no publisher.[16]

In early 1954, Ballard joined the Royal Air Force and was assigned to the Royal Canadian Air Force flight-training base in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, Canada. In that time, he encountered American science fiction magazines,[21] and, in due course, wrote his first science fiction story, "Passport to Eternity", a pastiche of the American science fiction genre; yet the story was not published until 1962.[16]

In 1955, Ballard left the RAF and returned to England,[23] where he met and married Helen Mary Matthews, who was a secretary at the Daily Express newspaper; the first of three Ballard children was born in 1956.[24] In December 1956, Ballard became a professional science-fiction writer with the publication of the short stories "Escapement" (in New Worlds magazine) and "Prima Belladonna" (in Science Fantasy magazine).[25] At the New Worlds magazine, the editor, Edward J. Carnell, greatly supported Ballard's science-fiction writing, and published most of his early stories.

From 1958 onwards, Ballard was assistant editor of the scientific journal Chemistry and Industry.[26] His interest in art involved the emerging Pop Art movement, and, in the late 1950s, Ballard exhibited collages that represented his ideas for a new kind of novel. Moreover, his avant-garde inclinations discomfited writers of mainstream science fiction, whose artistic attitudes Ballard considered philistine. Briefly attending the 1957 World Science Fiction Convention in London, Ballard left disillusioned and demoralised by the type and quality of the science-fiction writing he encountered, and did not write another story for a year;[27] however, by 1965, he was editor of Ambit, an avante-garde magazine, which had an editorial remit amenable to his aesthetic ideals.[28][29]

Professional writer

[edit]In 1960, the Ballard family moved to Shepperton, Surrey, where he resided till his death in 2009.[30][31] To become a professional writer, Ballard forsook mainstream employment to write his first novel, The Wind from Nowhere (1962), during a fortnight holiday,[29] and quit his editorial job with the Chemistry and Industry magazine. Later that year, his second novel, The Drowned World (1962), also was published; those two novels established Ballard as a notable writer of New Wave science fiction; he also popularized the related concept and genre of inner space.[32]: 415 [33][34]: 260 From that success followed the publication of short-story collections, and was the beginning of a great period of literary productivity from which emerged the short-story collection "The Terminal Beach" (1964).

In 1964, Mary Ballard died of pneumonia, leaving Ballard to raise their three children, James, Fay and Bea Ballard. Although he did not remarry, his friend Michael Moorcock introduced Claire Walsh to Ballard, who later became his partner.[35] Claire Walsh worked in publishing during the 1960s and the 1970s, and was Ballard's sounding board for his story ideas; later, Claire introduced Ballard to the expatriate community in Sophia Antipolis, in southern France; those expatriates provided grist for the writer's mill.[36]

In 1965, after the death of his wife Mary, Ballard's writing yielded the thematically-related short stories, that were published in New Worlds by Moorcock, as The Atrocity Exhibition (1970). In 1967, the novelist Algis Budrys said that Brian W. Aldiss, Roger Zelazny, Samuel R. Delany and J. G. Ballard were the leading writers of New Wave Science Fiction.[37] In the event, The Atrocity Exhibition proved legally controversial in the U.S., because the publisher feared libel-and-slander lawsuits by the living celebrities who featured in the science fiction stories.[38] In The Atrocity Exhibition, the story titled "Crash!" deals with the psychosexuality of car-crash enthusiasts; in 1970, at the New Arts Laboratory, Ballard sponsored an exhibition of damaged automobiles titled "Crashed Cars"; lacking the commentary of an art curator, the artwork provoked critical vitriol and layman vandalism.[39] In the story "Crash!" and in the "Crashed Cars" exhibition, Ballard presented and explored the sexual potential in a car crash, which theme he also explored in a short film made with Gabrielle Drake in 1971. Those interests produced the novel Crash (1973), which features a protagonist named James Ballard, who lives in Shepperton, Surrey, England.[39]

Crash was also controversial upon publication.[40] In 1996, the film adaptation by David Cronenberg was met by a tabloid uproar in the UK, with the Daily Mail campaigning for it to be banned.[41] In the years following the initial publication of Crash, Ballard produced two further novels: 1974's Concrete Island, about a man stranded in the traffic-divider island of a high-speed motorway,[42] and High-Rise, about a modern luxury high-rise apartment building's descent into tribal warfare.[43]

Ballard published several novels and short story collections throughout the 1970s and 1980s, but his breakthrough into the mainstream came with Empire of the Sun in 1984, based on his years in Shanghai and the Lunghua internment camp. It became a best-seller,[44] was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and awarded the Guardian Fiction Prize and James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction.[45] It made Ballard known to a wider audience, although the books that followed failed to achieve the same degree of success. Empire of the Sun was filmed by Steven Spielberg in 1987, starring a young Christian Bale as Jim (Ballard). Ballard himself appears briefly in the film, and he has described the experience of seeing his childhood memories reenacted and reinterpreted as bizarre.[9][10]

Ballard continued to write until the end of his life, and also contributed occasional journalism and criticism to the British press. Of his later novels, Super-Cannes (2000) was well received,[46] winning the regional Commonwealth Writers' Prize.[47] These later novels often marked a move away from science fiction, instead engaging with elements of a traditional crime novel.[48] Ballard was offered a CBE in 2003, but refused, calling it "a Ruritanian charade that helps to prop up our top-heavy monarchy".[49][50] In June 2006, he was diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer, which metastasised to his spine and ribs. The last of his books published in his lifetime was the autobiography Miracles of Life, written after his diagnosis.[51] His final published short story, "The Dying Fall", appeared in the 1996 issue 106 of Interzone, a British sci-fi magazine. It was later reproduced in The Guardian on 25 April 2009.[52] He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

Posthumous publication

[edit]

In October 2008, before his death, Ballard's literary agent, Margaret Hanbury, brought an outline for a book by Ballard with the working title Conversations with My Physician: The Meaning, if Any, of Life to the Frankfurt Book Fair. The physician in question is oncologist Professor Jonathan Waxman of Imperial College London, who was treating Ballard for prostate cancer. While it was to be in part a book about cancer, and Ballard's struggle with it, it reportedly was to move on to broader themes. In April 2009 The Guardian reported that HarperCollins announced that Ballard's Conversations with My Physician could not be finished and plans to publish it were abandoned.[53]

In 2013, a 17-page untitled typescript listed as "Vermilion Sands short story in draft" in the British Library catalogue and edited into an 8,000-word text by Bernard Sigaud appeared in a short-lived French reissue of the collection by Éditions Tristram (ISBN 978-2367190068) under the title "Le labyrinthe Hardoon" as the first story of the cycle, tentatively dated "late 1955/early 1956" by B. Sigaud, David Pringle and Christopher J. Beckett. Reports From the Deep End, an anthology of short stories inspired by J. G. Ballard (London: Titan Books, 2023, edited by Maxim Jakubowski and Rick McGrath), could have included "The Hardoon Labyrinth"—the original edition by B. Sigaud enriched to about 9,400 words by D. Pringle—but opposition from the J. G. Ballard Estate terminated the project.[54][55][56][57]

Archive

[edit]In June 2010 the British Library acquired Ballard's personal archives under the British government's acceptance in lieu scheme for death duties. The archive contains eighteen holograph manuscripts for Ballard's novels, including the 840-page manuscript for Empire of the Sun, plus correspondence, notebooks, and photographs from throughout his life.[58] In addition, two typewritten manuscripts for The Unlimited Dream Company are held at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.[59]

Dystopian fiction

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

With the exception of his autobiographical novels, Ballard most commonly wrote in the post-apocalyptic dystopia genre.

His most celebrated novel in this regard is Crash, in which the characters (the protagonist, called Ballard, included) become increasingly obsessed with the violent psychosexuality of car crashes in general, and celebrity car crashes in particular. Ballard's novel was turned into a controversial film by David Cronenberg.[60]

Particularly revered among Ballard's admirers is his short story collection Vermilion Sands (1971), set in an eponymous desert resort town inhabited by forgotten starlets, insane heirs, very eccentric artists, and the merchants and bizarre servants who provide for them. Each story features peculiarly exotic technology such as cloud-carving sculptors performing for a party of eccentric onlookers, poetry-composing computers, orchids with operatic voices and egos to match, phototropic self-painting canvases, etc. In keeping with Ballard's central themes, most notably technologically mediated masochism, these tawdry and weird technologies service the dark and hidden desires and schemes of the human castaways who occupy Vermilion Sands, typically with psychologically grotesque and physically fatal results. In his introduction to Vermilion Sands, Ballard cites this as his favourite collection.

In a similar vein, his collection Memories of the Space Age explores many varieties of individual and collective psychological fallout from—and initial deep archetypal motivations for—the American space exploration boom of the 1960s and 1970s.

Will Self has described much of his fiction as being concerned with "idealised gated communities; the affluent, and the ennui of affluence [where] the virtualised world is concretised in the shape of these gated developments." He added in these fictional settings "there is no real pleasure to be gained; sex is commodified and devoid of feeling and there is no relationship with the natural world. These communities then implode into some form of violence."[61] Budrys, however, mocked his fiction as "call[ing] for people who don't think ... to be the protagonist of a J. G. Ballard novel, or anything more than a very minor character therein, you must have cut yourself off from the entire body of scientific education".[62]

In addition to his novels, Ballard made extensive use of the short story form. Many of his earliest published works in the 1950s and 1960s were short stories, including influential works like Chronopolis.[63] In an essay on Ballard, Will Wiles notes how his short stories "have a lingering fascination with the domestic interior, with furnishing and appliances", adding, "it's a landscape that he distorts until it shrieks with anxiety". He concludes that "what Ballard saw, and what he expressed in his novels, was nothing less than the effect that the technological world, including our built environment, was having upon our minds and bodies."[64]

Ballard coined the term inverted Crusoeism. Whereas the original Robinson Crusoe became a castaway against his own will, Ballard's protagonists often choose to maroon themselves; hence inverted Crusoeism (e.g., Concrete Island). The concept provides a reason as to why people would deliberately maroon themselves on a remote island; in Ballard's work, becoming a castaway is as much a healing and empowering process as an entrapping one, enabling people to discover a more meaningful and vital existence.

Television

[edit]On 13 December 1965, BBC Two screened an adaptation of the short story "Thirteen to Centaurus" directed by Peter Potter. The one-hour drama formed part of the first season of Out of the Unknown and starred Donald Houston as Dr. Francis and James Hunter as Abel Granger.[65] In 2003, Ballard's short story "The Enormous Space" (first published in the science fiction magazine Interzone in 1989, subsequently printed in the collection of Ballard's short stories War Fever) was adapted into an hour-long television film for the BBC entitled Home by Richard Curson Smith, who also directed it. The plot follows a middle-class man who chooses to abandon the outside world and restrict himself to his house, becoming a hermit.

Influence

[edit]Ballard is cited as an important forebear of the cyberpunk movement by Bruce Sterling in his introduction to the Mirrorshades anthology, and by author William Gibson.[66] Ballard's parody of American politics, the pamphlet "Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan", which was subsequently included as a chapter in his experimental novel The Atrocity Exhibition, was photocopied and distributed by pranksters at the 1980 Republican National Convention. In the early 1970s, Bill Butler, a bookseller in Brighton, was prosecuted under UK obscenity laws for selling the pamphlet.[67]

In his 2002 book Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals, the philosopher John Gray acknowledges Ballard as a major influence on his ideas. The book's publisher quotes Ballard as saying, "Straw Dogs challenges all our assumptions about what it is to be human, and convincingly shows that most of them are delusions."[68] Gray wrote a short essay, in the New Statesman, about a dinner he had with Ballard in which he stated, "Unlike many others, it wasn't his dystopian vision that gripped my imagination. For me his work was lyrical—an evocation of the beauty that can be gleaned from landscapes of desolation."[69]

According to literary theorist Brian McHale, The Atrocity Exhibition is a "postmodernist text based on science fiction topoi".[70][71]

Lee Killough directly cites Ballard's seminal Vermilion Sands short stories as the inspiration for her collection Aventine, also a backwater resort for celebrities and eccentrics where bizarre or frivolous novelty technology facilitates the expression of dark intents and drives. Terry Dowling's milieu of Twilight Beach is also influenced by the stories of Vermilion Sands and other Ballard works.[72]

In Simulacra and Simulation, Jean Baudrillard hailed Crash as the "first great novel of the universe of simulation".[73]

Ballard also had an interest in the relationship between various media. In the early 1970s, he was one of the trustees of the Institute for Research in Art and Technology.[74]

In popular music

[edit]Ballard has had a notable[75] influence on popular music, where his work has been used as a basis for lyrical imagery, particularly amongst British post-punk and industrial groups. Examples include albums such as Metamatic by John Foxx and The Atrocity Exhibition... Exhibit A by Exodus, various songs by Joy Division (most famously "Atrocity Exhibition" from Closer and "Disorder" from Unknown Pleasures),[76] "High Rise" by Hawkwind,[76] "Miss the Girl" by Siouxsie Sioux's second band The Creatures (based on Crash), "Down in the Park" by Gary Numan, "Chrome Injury" by The Church, "Drowned World/Substitute for Love" by Madonna,[77] "Warm Leatherette" by The Normal[78] and Atrocity Exhibition by Danny Brown.[79][80][81] Songwriters Trevor Horn and Bruce Woolley credit Ballard's story "The Sound-Sweep" with inspiring The Buggles' hit "Video Killed the Radio Star",[82] and the Buggles' second album included a song entitled "Vermillion Sands".[83] The 1978 post-punk band Comsat Angels took their name from one of Ballard's short stories.[84] An early instrumental track by British electronic music group The Human League "4JG" bears Ballard's initials as a homage to the author (intended as a response to "2HB" by Roxy Music).[85]

The Welsh rock band Manic Street Preachers include a sample from an interview with Ballard in their song "Mausoleum".[86] Additionally, the Manic Street Preachers song, "A Billion Balconies Facing the Sun", is taken from a line in the J. G. Ballard novel Cocaine Nights. The English band Klaxons named their debut album Myths of the Near Future after one of Ballard's short story collections.[87] The band Empire of the Sun took their name from Ballard's novel.[87] The American rock band The Sound of Animals Fighting took the name of the song "The Heraldic Beak of the Manufacturer's Medallion" from Crash. UK-based drum and bass producer Fortitude released an EP in 2016 called "Kline Coma Xero" named after characters in The Atrocity Exhibition. The song "Terminal Beach" by the American band Yacht is a tribute to his short story collection that goes by the same name.[citation needed] American indie musician and comic book artist Jeffrey Lewis mentions Ballard by name in his song "Cult Boyfriend", on the record A Turn in The Dream-Songs (2011), in reference to Ballard's cult following as an author.[88]

In the 2024 Met Gala

[edit]The 2024 Met Gala dress code was "The Garden of Time", inspired by Ballard's 1962 short story "The Garden of Time".[89]

Awards and honours

[edit]- 1979 BSFA Award for Best Novel for The Unlimited Dream Company[90]

- 1984 Guardian Fiction Prize for Empire of the Sun[91]

- 1984 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction for Empire of the Sun[45]

- 1984 Empire of the Sun shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction[92]

- 1997 De Montfort University Honorary doctorate.[93]

- 2001 Commonwealth Writers' Prize (Europe & South Asia region) for Super-Cannes[94]

- 2008 Golden PEN Award[95]

- 2009 Royal Holloway University of London Posthumous honorary doctorate[96]

Works

[edit]Novels

[edit]- The Wind from Nowhere (1961)

- The Drowned World (1962)

- The Burning World (1964; also The Drought, 1965)

- The Crystal World (1966)

- The Atrocity Exhibition (1970, first published as Love and Napalm: Export USA, 1972)

- Crash (1973)

- Concrete Island (1974)

- High-Rise (1975)

- The Unlimited Dream Company (1979)

- Hello America (1981)

- Empire of the Sun (1984)

- The Day of Creation (1987)

- Running Wild (1988)

- The Kindness of Women (1991)

- Rushing to Paradise (1994)

- Cocaine Nights (1996)

- Super-Cannes (2000)

- Millennium People (2003)

- Kingdom Come (2006)

Short story collections

[edit]- The Voices of Time and Other Stories (1962)

- Billennium (1962)

- Passport to Eternity (1963)

- The 4-Dimensional Nightmare (1963)

- The Terminal Beach (1964)

- The Impossible Man (1966)

- The Overloaded Man (1967)

- The Disaster Area (1967)

- The Day of Forever (1967)

- Vermilion Sands (1971)

- Chronopolis and Other Stories (1971)

- Low-Flying Aircraft and Other Stories (1976)

- The Best of J. G. Ballard (1977)

- The Best Short Stories of J. G. Ballard (1978)

- The Venus Hunters (1980)

- Myths of the Near Future (1982)

- The Voices of Time (1985)

- Memories of the Space Age (1988)

- War Fever (1990)

- The Complete Short Stories of J. G. Ballard (2001)[97]

- The Complete Short Stories of J. G. Ballard: Volume 1 (2006)[97]

- The Complete Short Stories of J. G. Ballard: Volume 2 (2006)[97]

- The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard (2009)

Non-fiction

[edit]- A User's Guide to the Millennium: Essays and Reviews (1996)

- Miracles of Life (autobiography; 2008)

Interviews

[edit]- Paris Review – J.G. Ballard (1984)

- Re/Search No. 8/9: J.G. Ballard (1985)

- J.G. Ballard: Quotes (2004)

- J.G. Ballard: Conversations (2005)[98]

- Extreme Metaphors (interviews; 2012)

Adaptations

[edit]Films

[edit]- When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970, Val Guest)

- Empire of the Sun (1987, Steven Spielberg)

- Crash (1996, David Cronenberg)

- The Atrocity Exhibition (2000, Jonathan Weiss)[99]

- Low-Flying Aircraft (2002, Solveig Nordlund)

- High-Rise (2015, Ben Wheatley)

Television

[edit]- "Thirteen to Centaurus" (1965) from the short story of the same name – dir. Peter Potter (BBC Two)

- Crash! (1971) dir. Harley Cokliss[100]

- "Minus One" (1991) from the story of the same name – short film dir. by Simon Brooks.

- "Home" (2003) primarily based on "The Enormous Space" – dir. Richard Curson Smith (BBC Four)

- "The Drowned Giant" (2021) from the short story of the same name, is the eighth episode of the second season of the Netflix anthology series Love, Death & Robots

Radio

[edit]- In Nov/Dec 1988, CBC Radio's sci-fi series Vanishing Point ran a seven-episode miniseries of The Stories of J. G. Ballard, which included audio adaptations of "Escapement," "Dead Astronaut," "The Cloud Sculptors of Coral D," "Low Flying Aircraft," "A Question of Re-entry," "News from the Sun" and "Having a Wonderful Time".

- In June 2013, BBC Radio 4 broadcast adaptions of The Drowned World and Concrete Island as part of a season of dystopian fiction entitled Dangerous Visions.[101]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Alumni and Fellows". Queen Mary University of London. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Jones, Thomas (10 April 2008). "Thomas Jones reviews 'Miracles of Life' by J.G. Ballard • LRB 10 April 2008". London Review of Books. pp. 18–20. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Dibbell, Julian (February 1989). "Weird Science". Spin Magazine.

- ^ "Empire of the Sun (1984)". Ballardian. 16 September 2006. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ "About". Ballardian. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Will Self, 'Ballard, James Graham (1930–2009)' Archived 17 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, January 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013, (subscription required)

- ^ a b Pringle, D. (Ed.) and Ballard, J.G. (1982). "From Shanghai to Shepperton". Re/Search 8/9: J.G. Ballard: 112–124. ISBN 0-940642-08-5.

- ^ "JG Ballard in Shanghai". Timeoutshanghai.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ a b Ballard, J.G. (4 March 2006). "Look back at Empire Archived 11 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ a b "J.G. Ballard". Jgballard.ca. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Cowley, J. (4 November 2001). "The Ballard of Shanghai jail Archived 24 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine". The Observer. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ a b Livingstone, D.B. (1996?). "J.G. Ballard: Crash: Prophet with Honour Archived 21 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 12 March 2006.

- ^ Hall, C. "JG Ballard: Extreme Metaphor: A Crash Course in the Fiction Of JG Ballard Archived 25 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ Welch, Frances. "All Praise and Glory to the Mind of Man"

- ^ Campbell, James (14 June 2008). "Strange Fiction". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c Pringle, David (19 April 2009). "Obituary:JG Ballard". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ Frick, Interviewed by Thomas (21 May 1984). "J. G. Ballard, The Art of Fiction No. 85". The Paris Review. Winter 1984 (94). Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "The Papers of James Graham Ballard – Archives Hub". Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Collecting 'The Violent Noon' and other assorted Ballardiana". Ballardian. 5 February 2007. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ "Notable Alumni/ Arts and Culture". Queen Mary, University of London. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ a b Jones, Thomas (10 April 2008). "Whisky and Soda Man". London Review of Books. pp. 18–20. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "'What exactly is he trying to sell?': J.G. Ballard's Adventures in Advertising, part 1". Ballardian.com. 4 May 2009. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ London Gazette, 1 July 1955.

- ^ "JG Ballard's Daughter on the Mother who Could Never be Mentioned". the Guardian. 20 June 2014.

- ^ Weber, Bruce (21 April 2009). "J.G Ballard, novelist, Is Dead at 78". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Bonsall, Mike (1 August 2007). "JG Ballard's Experiment in Chemical Living". Ballardian.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ "JG Ballard Interviewed by Jannick Storm". Jgballard.ca. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ "JGB in Ambit Magazine". Jgballard.ca. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ a b "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/101436. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Clark, Alex (9 September 2000). "Microdoses of madness". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ Smith, Karl (7 October 2012). "The Velvet Underground of English Letters: Simon Sellars Discusses J.G. Ballard". thequietus.com. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ Stableford, Brian M. (2006). Science fact and science fiction: an encyclopedia. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97460-8.

- ^ Clute, John; David, Langford; Nicholls, Peter. "SFE: Inner Space". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Mayo, Rob (16 September 2019). "The Myth of Dream-Hacking and 'Inner Space' in Science Fiction, 1948-201". In Taylor, Steven J.; Brumby, Alice (eds.). Healthy Minds in the Twentieth Century: In and Beyond the Asylum (PDF). Mental Health in Historical Perspective. Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-27275-3. ISBN 978-3-030-27275-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "Author J. G. Ballard dies at 78", Deseret News, 20 April 2009, p. A12

- ^ Self, Will (15 October 2014). "Claire Walsh obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ Budrys, Algis (October 1967). "Galaxy Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 188–194.

- ^ "1991 Science Fiction Eye magazine article on Atrocity Exhibition". jgballard.ca. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ a b Ballard, J.G. (1993). The Atrocity Exhibition (expanded and annotated edition). ISBN 0-00-711686-1.

- ^ Francis, Sam (2008). "'Moral Pornography' and 'Total Imagination': The Pornographic in J. G. Ballard's Crash". English. 57 (218): 146–168. doi:10.1093/english/efn011.

- ^ Barker, Martin; Arthurs, Jane & Harindranath, Ramaswami (2001). The Crash Controversy: Censorship Campaigns and Film Reception. Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-1-903364-15-4. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

- ^ Sellars, Simon (16 September 2006). "Concrete Island (1974)". Ballardian. Archived from the original on 29 October 2006. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (28 September 2015). "New Film High-Rise Explores The Symbolism and Terror of Tower Living". Curbed. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ Collinson, G. "Empire of the Sun Archived 6 February 2004 at the Wayback Machine". BBC Four article on the film and novel. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ a b "James Tait Black Prizes Fiction Winners". University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ Moss, Stephen (13 September 2000). "Mad about Ballard". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ "J. G. Ballard". British Council Literature. British Council. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Noys, Benjamin (2007). "La libido réactionnaire?: the recent fiction of J.G. Ballard". Sage Publishers. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ Branigan, Tania (22 December 2003). "'It's a pantomime where tinsel takes the place of substance'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ Lea, Richard and Adetunji, Jo (19 April 2009). "Crash author JG Ballard, 'a giant on the world literary scene', dies aged 78". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ Wavell, Stuart (20 January 2008). "Dissecting bodies from the twilight zone: Stuart Wavell meets JG Ballard". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- ^ Ballard, JG (24 April 2009). "The Dying Fall by JG Ballard". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Thompson, Liz (16 October 2008). "Ballard and the meaning of life". BookBrunch. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- ^ Beckett, Chris (2011). "The Progress of the Text: The Papers of J. G. Ballard at the British Library". Electronic British Library Journal. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ Horrocks, Chris, "Disinterring the Present: Science Fiction, Media Technology and the Ends of the Archive", Journal of Visual Culture, 2013 Vol 12(3): 414–430

- ^ "Near Vermilion Sands: The Context and Date of Composition of an Abandoned Literary Draft by J. G. Ballard". Bl.uk. 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ King, Daniel (February 2014). ""'Again Last Night': A previously unpublished Vermilion Sands story", SF Commentary 86" (PDF). pp. 18–20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "Archive of JG Ballard saved for the nation". The British Library. 10 June 2010. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "Manuscripts for The Unlimited Dream Company". Harry Ransom Center. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ "JG Ballard – Prospect Magazine". Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ "John Gray and Will Self – JG Ballard". Watershed. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ Budrys, Algis (December 1966). "Galaxy Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 125–133.

- ^ Boyd, Jason (7 February 2019). "20 Most Influential Science Fiction Short Stories of the 20th Century". FictionPhile.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Wiles, Will (20 June 2017). "The Corner of Lovecraft and Ballard". Places Journal (2017). doi:10.22269/170620. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ ""Out of the Unknown" Thirteen to Centaurus (TV Episode 1965)". IMDb. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "For William Gibson, Seeing the Future Is Easy. But the Past?". The New York Times. 9 January 2020. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Holliday, Mike. ""A DIRTY AND DISEASED MIND": THE UNICORN BOOKSHOP OBSCENITY TRIAL". holli.co.uk. Mike Holliday. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Straw Dogs". Granta. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Gray, John (6 December 2018). "The night that changed my life: John Gray on having dinner with JG Ballard". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Brian McHale, Postmodernist Fiction ISBN 978-0-415-04513-1

- ^ Luckhurst, Roger. "Border Policing: Postmodernism and Science Fiction" Science Fiction Studies (November 1991)

- ^ "Terry Dowling". terrydowling.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ Baudrillard, Jean (1981). Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-472-06521-9.

- ^ "JG Ballard Interviewed by Douglas Reed". Jgballard.ca. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "What Pop Music Tells Us About J G Ballard". BBC News. 20 April 2009. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ a b "What pop music tells us about JG Ballard". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ "Madonna (New York, NY – July 25, 2001) – Feature". Slantmagazine.com. 26 July 2001. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ Myers, Ben. "JG Ballard: The music he inspired". The Guardian.

- ^ Young, Alex (18 July 2016). "Danny Brown has named his new album Atrocity Exhibition after the Joy Division song". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ "Danny Brown Announces New Album Title Atrocity Exhibition". Pitchfork. 18 July 2016. Archived from the original on 26 September 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ Renshaw, David (18 July 2016). "Danny Brown Names New Album Atrocity Exhibition". The Fader. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ "The Buggles 'Video Killed The Radio Star'". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ "Horniculture! • From the Art of Plastic to the Age of Noise". Trevorhorn.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010.

- ^ "Путеводитель по миру шоппинга – скидки, распродажи, акции – В мире модных брендов 23". Gothtronic.com. 21 November 2013. Archived from the original on 19 October 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ^ "The Human League's Phil Oakey is a man of letters – B is for Ballard". The Herald. Glasgow. 24 November 2011. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "What pop music tells us about JG Ballard". BBC News. 20 April 2009. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ a b "What pop music tells us about JG Ballard". 20 April 2009. Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2021 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "A Turn in the Dream-Songs (2011), by Jeffrey Lewis". Jeffrey Lewis. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "And the 2024 Met Gala Dress Code Is…". Vogue. 15 February 2024. Archived from the original on 15 February 2024. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ "1979 BSFA Awards". sfadb.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ "1984 Guardian JG Ballard interview by W.L. Webb". Jgballard.ca. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "The Man Booker Prize Archive 1969–2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Williams, Lynne (12 September 1997). "Honorary Degrees". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ "J.G. Ballard cops Commonwealth prize". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Golden Pen Award, official website". English PEN. Archived from the original on 21 November 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ "2009 Honorary Graduates". Royal Holloway University of London. 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ a b c None of the "complete" collections are in fact fully exhaustive, since they contain only some of the Atrocity Exhibition stories.

- ^ Deadhead, Daisy (8 December 2009). "We won't give pause until the blood is flowing". DeadAir. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2009.

- ^ "reel 23". Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Sellars, S. (10 August 2007). "Crash! Full-Tilt Autogeddon Archived 4 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine". Ballardian.com. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ Martin, Tim (14 June 2013). "Do have nightmares". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ballard, J.G. (1984). Empire of the Sun. ISBN 0-00-654700-1.

- Ballard, J.G. (1991). The Kindness of Women. ISBN 0-00-654701-X.

- Ballard, J.G. (1993). The Atrocity Exhibition (expanded and annotated edition). ISBN 0-00-711686-1.

- Ballard, J.G. (2006). "Look back at Empire Archived 11 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine". The Guardian, 4 March 2006.

- Baxter, J. (2001). "J.G. Ballard Archived 11 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine". The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 11 March 2006.

- Baxter, J. (ed.) (2008). J.G. Ballard, London: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-9726-0.

- Baxter, John (2011). The Inner Man: The Life of J. G. Ballard. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-86352-6.

- Brigg, Peter (1985). J.G. Ballard. Rpt. Borgo Press/Wildside Press. ISBN 0-89370-953-0.

- Collins English Dictionary. ISBN 0-00-719153-7. Quoted in Ballardian: The World of JG Ballard Archived 19 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 March 2006.

- Cowley, J. (2001). "The Ballard of Shanghai jail Archived 24 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine". Review of The Complete Stories by J.G. Ballard. The Observer, 4 November 2001. Retrieved 11 March 2006.

- Delville, Michel. J.G. Ballard. Plymouth: Northcote House, 1998.

- Gasiorek, A. (2005). J. G. Ballard. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7053-2

- Hall, C. "Extreme Metaphor: A Crash Course in the Fiction of JG Ballard Archived 25 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 11 March 2006.

- Livingstone, D. B. (1996?). "Prophet with Honour Archived 21 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 12 March 2006.

- Luckhurst, R. (1998). The Angle Between Two Walls: The Fiction of J. G. Ballard. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-831-7.

- McGrath, Rick (ed.). Deep Ends: The JG Ballard Anthology 2015. The Terminal Press. 2015. ISBN 978-0-9940982-0-7.

- McGrath, Rick (ed.). Deep Ends: The JG Ballard Anthology 2016. The Terminal Press. 2016. ISBN 978-0-9940982-5-2.

- McGrath, Rick (ed.). Deep Ends: A Ballardian Anthology 2018. The Terminal Press. 2018. ISBN 978-0-9940982-7-6.

- McGrath, Rick (ed.). Deep Ends: A Ballardian Anthology 2019. The Terminal Press. 2019. ISBN 978-1-7753679-0-1.

- McGrath, Rick (ed.). Deep Ends: A Ballardian Anthology 2020. The Terminal Press. 2020. ISBN 978-1-7753679-5-6.

- McGrath, R. JG Ballard Book Collection Archived 4 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 March 2006.

- McGrath, Rick (ed.). The JG Ballard Book. The Terminal Press. 2013. ISBN 978-0-9918665-1-9

- O'Connell, Mark (23 April 2020). "Why We Are Living in Ballard's World". Critic at Large. New Statesman. 149 (5514): 54–57.

- Oramus, Dominika. Grave New World. Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2007.

- Pringle, David, Earth is the Alien Planet: J.G. Ballard's Four-Dimensional Nightmare, San Bernardino, CA: The Borgo Press, 1979.

- Pringle, David (ed.) and Ballard, J.G. (1982). "From Shanghai to Shepperton". Re/Search 8/9: J.G. Ballard: 112–124. ISBN 0-940642-08-5.

- Rossi, Umberto (2009). "A Little Something about Dead Astronauts Archived 27 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine", Science-Fiction Studies, No. 107, 36:1 (March), 101–120.

- Stephenson, Gregory, Out of the Night and into the Dream: A Thematic Study of the Fiction of J.G. Ballard, New York: Greenwood Press, 1991.

- McGrath, Rick (ed.). Deep Ends: The JG Ballard Anthology 2014. The Terminal Press. 2014. ISBN 978-0-9918665-4-0.

- V. Vale (ed.) (2005). J.G. Ballard: Conversations (excerpts). RE/Search Publications. ISBN 1-889307-13-0.

- V. Vale and Ryan, Mike (eds.) (2005). J.G. Ballard: Quotes (excerpts). RE/Search Publications. ISBN 1-889307-12-2.

- Wilson, D. Harlan. Modern Masters of Science Fiction: J.G. Ballard. University of Illinois Press. 2017. ISBN 978-0-25-208295-5.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about J. G. Ballard at the Internet Archive

- J. G. Ballard at British Council: Literature

- J. G. Ballard at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- J. G. Ballard at IMDb

- Ballardian Archived 19 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine (Simon Sellars)

- J.G. Ballard Literary Archive & Bibliographies Archived 4 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine (Rick McGrath)

- 2008 profile of J. G. Ballard Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Theodore Dalrymple in City Journal magazine

- J. G. Ballard Literary Estate Archived 19 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- J G Ballard Archived 11 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine at the British Library

- J G Ballard[permanent dead link] archives and manuscripts catalogue at the British Library

Articles, reviews and essays

- Frick, Thomas (Winter 1984). "J. G. Ballard, The Art of Fiction No. 85". The Paris Review. Winter 1984 (94). Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- Landscapes From a Dream Archived 29 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, J G Ballard and modern art

- The Marriage of Reason and Nightmare, City Journal, Winter 2008 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Miracles of Life reviewed by Karl Miller Archived 17 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine in the Times Literary Supplement, 12 March 2008

- J.G. Ballard: The Glow of the Prophet Diane Johnson article on Ballard from The New York Review of Books

- Reviews of Ballard's work and John Foyster's criticism of Ballard's work featured in Edition 46 of Science Fiction magazine Archived 11 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine edited by Van Ikin.

- A review of Ballard's Running Wild J. G. Ballard's Running Wild – The Literary Life Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

Source material

- J. G. Ballard and his family on the list of the internment camp at Japan Center for Asian Historical Records Archived 2 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- J.G. Ballard and Scottish artist Sir Eduardo Paolozzi Archived 11 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

Obituaries and remembrances

- Obituary in the Times Online

- Obituary Archived 30 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine by John Clute in The Independent

- Obituary Archived 5 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine in the Los Angeles Times

- Quotes from other writers Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine on BBC News

- More writers' reactions in The Guardian

- A short appreciation Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine in The New Yorker

- Tribute by V. Vale from RE/Search

- Letter From London: The J.G. Ballard Memorial (Archived 27 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine)

- Self on Ballard by Will Self on BBC Radio 4, 26 September 2009 (Transcript and Postscript Archived 14 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine) at The Terminal Collection Archived 21 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine by Rick McGrath)

- 1930 births

- 2009 deaths

- 20th-century atheists

- 20th-century English short story writers

- 20th-century English male writers

- 20th-century English non-fiction writers

- 20th-century English novelists

- 20th-century English essayists

- 20th-century British memoirists

- 20th-century Royal Air Force personnel

- 21st-century atheists

- 21st-century English short story writers

- 21st-century English male writers

- 21st-century English non-fiction writers

- 21st-century English novelists

- 21st-century British essayists

- 21st-century English memoirists

- Alumni of King's College, Cambridge

- Alumni of Queen Mary University of London

- Anti-monarchists

- British copywriters

- British technology writers

- Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery

- Deaths from prostate cancer in England

- English atheists

- English autobiographers

- English crime writers

- English essayists

- English fantasy writers

- English historical novelists

- English literary critics

- English male journalists

- English male non-fiction writers

- English male novelists

- English male short story writers

- English republicans

- English satirists

- English science fiction writers

- English speculative fiction writers

- English thriller writers

- Futurologists

- Humor researchers

- Hyperreality theorists

- Irony theorists

- James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients

- Literacy and society theorists

- British literary theorists

- Magic realism writers

- Mass media theorists

- Metaphor theorists

- Opinion journalists

- Pamphleteers

- People educated at The Leys School

- People from the Shanghai International Settlement

- People from Shepperton

- Writers from Surrey

- British postmodern writers

- British psychological fiction writers

- Philosophers of pessimism

- Philosophers of technology

- Science fiction critics

- Surrealist writers

- Theorists on Western civilization

- Trope theorists

- British weird fiction writers

- World War II civilian prisoners held by Japan

- Writers about activism and social change

- Writers about globalization

- Writers from Shanghai

- Writers of historical fiction set in the modern age