Inchcolm

| Scottish Gaelic name | Innis Choluim |

|---|---|

| Meaning of name | Island of St Columba |

Inchcolm and Braefoot Bay | |

| Location | |

| OS grid reference | NT189827 |

| Coordinates | 56°02′N 3°18′W / 56.03°N 3.30°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Islands of the Forth |

| Area | 9 hectares (22 acres) |

| Highest elevation | 34 metres (112 feet) |

| Administration | |

| Council area | Fife |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 2[1] |

| References | [2][3][4][5] |

Inchcolm (from the Scottish Gaelic "Innis Choluim", meaning Columba's Island) is an island in the Firth of Forth in Scotland. The island has a long history as a site of religious worship, having started with a church, which later developed into a monastery and a large Augustine Abbey in the mid 13th century. It was repeatedly attacked by English raiders during the Wars of Scottish Independence, and was later fortified extensively with gun emplacements and other military facilities during both World Wars to defend nearby Edinburgh.

Inchcolm Abbey and the surrounding island are now in the care of Historic Scotland. The island is accessible to visitors during the day via private boat tours from Queensferry. Many of the religious buildings on Inchcolm remain in fair condition and Inchcolm is described as having the best-preserved cloister in Scotland.[6]

Geography

[edit]Inchcolm lies in the Firth of Forth off the south coast of Fife opposite Braefoot Bay, east of the Forth Bridge, south of Aberdour, Fife, and north of the City of Edinburgh. It is separated from the Fife mainland by a stretch of water known as Mortimer's Deep.[7] The island forms part of the parish of Aberdour, and lies a quarter of a mile from the shore. In the days when people were compelled to cross the Firth of Forth by boat as opposed to bridge, the island was a great deal less isolated, and on the ferry routes between Leith/Lothian and Fife.

The island can be broadly divided into three sections: the east, where its military defensive operations were centred during the Second World War, the lower central part, with the small natural harbour and shop, and a larger western end.

In 2001 there was a resident population of 2[8] but at the time of the 2011 census there were no "usual residents" recorded.[1]

History

[edit]

Early history

[edit]

Inchcolm was anciently known as Emona, Aemonia or Innis Choluim.[9] It may have been used by the Roman fleet in some capacity, as they had a strong presence at Cramond for a few years, and had to travel to the Antonine Wall.

It was supposedly visited by St Columba (an Irish missionary monk) in 567, and was named after him in the 12th century. As such, the present name Inchcolm means 'Island of Colm', with Inch a derogation of innish, Gaelic for Island and Colm believed to be a reference to St Columbia, whose relics were held at Dunkeld Cathedral, originally the head of Inchcolm's diocese.[10]

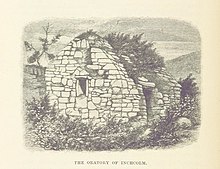

It is believed to have served the monks of the Columban family as an "Iona of the east" from early times. It was first established as a priory in the 1100s.[11] A primitive stone-roofed building survived on the island, preserved and given a vaulted roof by the monks of the later abbey, probably served as a hermit's oratory and cell in the 12th century, if not earlier. Fragments of carved stonework from the Dark Ages testify to an early Christian presence on the island. A hogback stone, preserved in the abbey's visitor centre, can be dated to the late 10th century, making it probably Scotland's earliest type of monument originating among Danish settlers in northern England. A 16th-century source states that a stone cross was situated nearby, although no features could be found which related to the monument. In 1235, the priory was made into an abbey.[11]

The island has a mention in Shakespeare's Macbeth:

- That now Sweno, the Norwayes King,

- Craves composition:

- Nor would we deigne him buriall of his men,

- Till he disbursed, at Saint Colmes ynch,

- Ten thousand Dollars, to our generall use

The reference in Shakespeare arose because Inchcolm was long used as an exclusive burial site (much like Iona). A Danish force under king Sweyn, the father of Canute, raided the island and Fife with an English force. In the play, Macbeth buys off the Danes with a "great summe of gold", and tells the Danes they could bury their dead there for "ten thousand dollars". Hector Boece corroborates the claim that the Danes paid good money to have their dead buried there in the 11th century. The practice of burying dead on islands in Scotland is long established – and was partly a deterrent to feral dogs and wolves (still found in Scotland at that point) which might dig up the corpses and eat them.

Like other centres of Culdee activity, the island was used as a home for hermits. The nearby Inchmickery's name also commemorates a probable hermit. Historical textual evidence suggests that this was the case in the 12th century, when King Alexander I was marooned on the island, and was said to have been looked after by a hermit on the island in 1123.[12] Alexander decided to make the island the site of an Augustinian monastery.[12]

The earliest known charter is in 1162, when the canons were already well established, and it was raised to the status of an abbey in 1235. Its buildings, including a widely visible square tower, a largely ruined church, cloisters, refectory and small chapter house, are the best preserved of any Scottish medieval monastic house. The ruins are under the care of Historic Scotland (entrance charge; ferry from South Queensferry).

Mortimer's Deep, the channel which separates Inchcolm from the mainland, supposedly got its name during this period when some monks of the island who had been tasked with transporting the body of Sir Alan Mortimer to be interred at the church there, instead disposed of his coffin in the sea.[13]

Walter Bower, Abbot 1418–49, was the author of the Latin Scotichronicon, one of Scotland's most important medieval historical sources. The island was part of the medieval diocese of Dunkeld (also dedicated to St Columba), and several of the medieval bishops were buried within the Abbey church.

Late Middle Ages and English raids

[edit]Like nearby Inchkeith and the Isle of May, Inchcolm was attacked repeatedly by English raiders in the 14th century. This was the period of the Scottish Wars of Independence, and decisive battles were being fought in the Lothians and in the Stirling/Bannockburn region, and so the island was effectively in the route of any supply or raiding vessels.

In 1335, there was an especially bad raid by an English ship when the abbey's treasures were stolen, along with a statue of Columba. The story goes that the ship was nearly wrecked on Inchkeith and had to dock at Kinghorn. The sailors taking a religious turn, thought that this was due to the wrath of Columba, returned the statue and treasures to the island, and experienced good weather on their outward journey.

In 1384, an English raid attempted to set alight Inchcolm Abbey, but this again was foiled by the weather – in this case a strong wind blew out the flames.

In 1441, the Abbot Walter Bower wrote an influential historical study of Scotland called the Scotichronicon.[14]

The island was used as a form of prison in the 14th and 15th centuries. Amongst those interned here were Archbishop Patrick Graham of St Andrews. In 1427, James I confined the mother of Alexander, Lord of the Isles. Mariota, Countess of Ross here.

Tudor and early modern period

[edit]In the 16th century, the island suffered further English depredation. In 1547, after the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh, Inchcolm was fortified by the English, like nearby Inchgarvie - while Inchkeith was occupied by their Italian mercenaries for two years. Sir John Luttrell garrisoned the island with 100 hagbutters and 50 labourers on Saturday 17 September 1547.[15] Early in October 1547, the Earl of Angus attempted to recapture the island with five ships. An inventory of 8 January 1548 lists the English armaments on the island as; one culverin; one demi-culverin; 3 iron sakers; a brass saker; 2 iron falcons; 3 brass falcons; 4 fowlers; 2 port pieces; 14 bases; 90 arquebuses, 2 chests of bows; 50 pikes; and 40 bills.[16] The English commander, John Luttrell, abandoned the island and destroyed the fortifications he had made at the end of April 1548.[17]

After the Protestant Scottish reformation of 1560, the island monastic community and abbey was disbanded.[18] However, due to their island location, Inchcolm's religious buildings are in better condition than most of those on the mainland as they could not be so easily destroyed by proactive Reformers.

In the 16th century it became the property of Sir James Stewart, whose grandson became third Earl of Moray by virtue of his marriage to the elder daughter of the first earl. From it comes the earl's title of Lord St Colme (1611).

In the 1880s, a skeleton was found built into one of the abbey's walls. It was standing upright and is of unknown date.

Military defences

[edit]During both the First World War and the Second World War, Inchcolm was part of the defences of the Firth of Forth.[19] Inchcolm was the HQ of what were called in the First World War the 'Middle defences', the main element of which was a continuous anti-submarine and anti-boat boom across the river. The defences were intended to protect the naval anchorage between Inchcolm and the Forth Rail Bridge (as there was no longer room above the bridge to moor all the ships based in the Forth).

The defences of Inchcolm were significantly strengthened in 1916-17 when it was decided to move the Grand Fleet from Scapa Flow to the Forth. As part of these works 576 Cornwall Works Company, Royal Engineers, built a tunnel under the hill at the east end of the island, to link a new battery of guns to their magazine, on the protected side of the island.[19] The tunnel is dated 1916–17. At the east end of the island, there were emplacements for two 12-pounder and two twin 6-pounder guns.[19]

The First World War engine house (which powered the defence searchlights) was adapted in the 1930s as a visitor centre, which it is still used by Historic Scotland. The island was re-occupied in 1939, when the anti-submarine and anti-boat boom was once again laid across the estuary. Some the military structures from both the First and Second World Wars survive and remain in situ.[19] These include a First World War drying hut, and the brick building in which the staff of the NAAFI lived in the Second World War.[19] Other surviving buildings include engine rooms, searchlight emplacements, storerooms and officers rooms. The main officers rooms, mess and barrack blocks were cited in the middle and west of the island.[19] Many of the wartime defence structures were deliberately partly demolished in the early 1960s by the engineers of the Territorial Army.[19]

Tourist attraction

[edit]

There are currently two ferry services and one charter yacht company that operate trips to Inchcolm island, and allow passengers 1.5 hours to explore the island. The Maid of the Forth[20] and the Forth Belle[21] both operate from the Hawes Pier in South Queensferry between Easter and late October.

The main feature of the island is the former Augustinian Inchcolm Abbey (Historic Scotland), Scotland's most complete surviving monastic house. In former times, and perhaps partly due to its dedication to Columba, it was sometimes nicknamed 'Iona of the East'. The well-preserved abbey and ruins of the 9th-century hermit's cells attract visitors to the island.[7]

It was the home of a religious community linked with St Colm or St Columba, the 6th-century Abbot of Iona. King Alexander I was storm-bound on the island for three days in 1123 and in recognition of the shelter given to him by the hermits, promised to establish a monastic settlement in honour of St Columba. Though the king died before the promise could be fulfilled, his brother David I later founded a priory here for monks of the Augustinian order; the priory was erected into an abbey in 1223.

Wildlife

[edit]

The west end of the island is home to a large colony of seagulls and fulmars. They nest extensively on the island between April and August.[22]

Seals are commonly spotted around the island and basking on neighbouring outcrops. There are no stoats or hedgehogs on the island; thus, eggs can often be found on the ground.

Between April and July puffins nest on the Northern rockface of the island and can be seen bobbing around in the water as the search for food before flying back to their burrows.

The island is also home to one of the very few colonies of black rats in Britain.[23]

Today the island is inhabited by the Historic Scotland monument manager and a residential steward, along with non-resident staff duties include running the shop, maintaining the site and assisting with landing boats.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- ^ Ordnance Survey

- ^ Iain Mac an Tailleir. "Placenames" (PDF). Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ Area estimate from Morris, Ron (2003) "The Wildlife of Inchcolm :" [permanent dead link] Hillside. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- ^ Inchcolm Abbey and Island. Historic Scotland. 2011. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-84917-257-8.

- ^ a b "Overview of Inchcolm". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ Márkus, Gilbert (2004). "Tracing Emon: Insula Sancti Columbae de Emonia". The Innes Review. 55 (1). Edinburgh University Press (subscription required): 1–2. doi:10.3366/inr.2004.55.1.1.

- ^ Inchcolm Abbey and Island. Historic Scotland. 2011. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84917-257-8.

- ^ a b Inchcolm Abbey and Island. Historic Scotland. 2011. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84917-257-8.

- ^ a b Inchcolm Abbey and Island. Historic Scotland. 2011. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84917-257-8.

- ^ Sibbald, Robert (1803). The history ... of the sheriffdoms of Fife and Kinross. p. 92.

- ^ Inchcolm Abbey and Island. Historic Scotland. 2011. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-84917-257-8.

- ^ Patten, William, The Expedition in Scotland 1547, (1548).

- ^ Starkey, David, ed., The Inventory of Henry VIII, Society of Antiquaries (1998), 144.

- ^ Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 1 (1898), 24, 90 Andrew Dudley and Luttrel to Somerset

- ^ Inchcolm Abbey and Island. Historic Scotland. 2011. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84917-257-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Inchcolm Abbey and Island. Historic Scotland. 2011. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-84917-257-8.

- ^ "Maid of the Forth".

- ^ "Forth Tours".

- ^ Inchcolm Abbey and Island. Historic Scotland. 2011. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-84917-257-8.

- ^ "Revealed: Historic Scottish island home to black rats | The Scotsman".

- Collins Encyclopedia of Scotland

External links

[edit]- RCAHMS - The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland

- Cyberscotia's page on the island - Includes maps, drawings, and photographs

- Report of overnight stay on the island