Infantry

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

Infantry is a specialization of military personnel who engage in warfare combat. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, irregular infantry, heavy infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry, mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and naval infantry. Other types of infantry, such as line infantry and mounted infantry, were once commonplace but fell out of favor in the 1800s with the invention of more accurate and powerful weapons.

Etymology and terminology

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

In English, use of the term infantry began about the 1570s, describing soldiers who march and fight on foot. The word derives from Middle French infanterie, from older Italian (also Spanish) infanteria (foot soldiers too inexperienced for cavalry), from Latin īnfāns (without speech, newborn, foolish), from which English also gets infant.[1] The individual-soldier term infantryman was not coined until 1837.[2] In modern usage, foot soldiers of any era are now considered infantry and infantrymen.[3]

From the mid-18th century until 1881, the British Army named its infantry as numbered regiments "of Foot" to distinguish them from cavalry and dragoon regiments (see List of Regiments of Foot).[citation needed]

Infantry equipped with special weapons were often named after that weapon, such as grenadiers for their grenades, or fusiliers for their fusils. These names can persist long after the weapon speciality; examples of infantry units that retained such names are the Royal Irish Fusiliers and the Grenadier Guards.[citation needed]

Dragoons were created as mounted infantry, with horses for travel between battles; they were still considered infantry since they dismounted before combat. However, if light cavalry was lacking in an army, any available dragoons might be assigned their duties; this practice increased over time, and dragoons eventually received all the weapons and training as both infantry and cavalry, and could be classified as both. Conversely, starting about the mid-19th century, regular cavalry have been forced to spend more of their time dismounted in combat due to the ever-increasing effectiveness of enemy infantry firearms. Thus most cavalry transitioned to mounted infantry. As with grenadiers, the dragoon and cavalry designations can be retained long after their horses, such as in the Royal Dragoon Guards, Royal Lancers, and King's Royal Hussars.[citation needed]

Similarly, motorised infantry have trucks and other unarmed vehicles for non-combat movement, but are still infantry since they leave their vehicles for any combat. Most modern infantry have vehicle transport, to the point where infantry being motorised is generally assumed, and the few exceptions might be identified as modern light infantry. Mechanised infantry go beyond motorised, having transport vehicles with combat abilities, armoured personnel carriers (APCs), providing at least some options for combat without leaving their vehicles. In modern infantry, some APCs have evolved to be infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs), which are transport vehicles with more substantial combat abilities, approaching those of light tanks. Some well-equipped mechanised infantry can be designated as armoured infantry. Given that infantry forces typically also have some tanks, and given that most armoured forces have more mechanised infantry units than tank units in their organisation, the distinction between mechanised infantry and armour forces has blurred.[citation needed]

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

The first military forces in history were infantry. In antiquity, infantry were armed with early melee weapons such as a spear, axe, or sword, or an early ranged weapon like a javelin, sling, or bow, with a few infantrymen being expected to use both a melee and a ranged weapon. With the development of gunpowder, infantry began converting to primarily firearms. By the time of Napoleonic warfare, infantry, cavalry and artillery formed a basic triad of ground forces, though infantry usually remained the most numerous. With armoured warfare, armoured fighting vehicles have replaced the horses of cavalry, and airpower has added a new dimension to ground combat, but infantry remains pivotal to all modern combined arms operations.[citation needed]

The first warriors, adopting hunting weapons or improvised melee weapons,[4] before the existence of any organised military, likely started essentially as loose groups without any organisation or formation. But this changed sometime before recorded history; the first ancient empires (2500–1500 BC) are shown to have some soldiers with standardised military equipment, and the training and discipline required for battlefield formations and manoeuvres: regular infantry.[5] Though the main force of the army, these forces were usually kept small due to their cost of training and upkeep, and might be supplemented by local short-term mass-conscript forces using the older irregular infantry weapons and tactics; this remained a common practice almost up to modern times.[6]

Before the adoption of the chariot to create the first mobile fighting forces c. 2000 BC,[7] all armies were pure infantry. Even after, with a few exceptions like the Mongol Empire, infantry has been the largest component of most armies in history.[citation needed]

In the Western world, from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages (c. 8th century BC to 15th century AD), infantry are categorised as either heavy infantry or light infantry. Heavy infantry, such as Greek hoplites, Macedonian phalangites, and Roman legionaries, specialised in dense, solid formations driving into the main enemy lines, using weight of numbers to achieve a decisive victory, and were usually equipped with heavier weapons and armour to fit their role. Light infantry, such as Greek peltasts, Balearic slingers, and Roman velites, using open formations and greater manoeuvrability, took on most other combat roles: scouting, screening the army on the march, skirmishing to delay, disrupt, or weaken the enemy to prepare for the main forces' battlefield attack, protecting them from flanking manoeuvers, and then afterwards either pursuing the fleeing enemy or covering their army's retreat.[citation needed]

After the fall of Rome, the quality of heavy infantry declined, and warfare was dominated by heavy cavalry,[8] such as knights, forming small elite units for decisive shock combat, supported by peasant infantry militias and assorted light infantry from the lower classes. Towards the end of Middle Ages, this began to change, where more professional and better trained light infantry could be effective against knights, such as the English longbowmen in the Hundred Years' War. By the start of the Renaissance, the infantry began to return to a larger role, with Swiss pikemen and German Landsknechts filling the role of heavy infantry again, using dense formations of pikes to drive off any cavalry.[9]

Dense formations are vulnerable to ranged weapons. Technological developments allowed the raising of large numbers of light infantry units armed with ranged weapons, without the years of training expected for traditional high-skilled archers and slingers. This started slowly, first with crossbowmen, then hand cannoneers and arquebusiers, each with increasing effectiveness, marking the beginning of early modern warfare, when firearms rendered the use of heavy infantry obsolete. The introduction of musketeers using bayonets in the mid 17th century began replacement of the pike with the infantry square replacing the pike square.[10]

To maximise their firepower, musketeer infantry were trained to fight in wide lines facing the enemy, creating line infantry. These fulfilled the central battlefield role of earlier heavy infantry, using ranged weapons instead of melee weapons. To support these lines, smaller infantry formations using dispersed skirmish lines were created, called light infantry, fulfilling the same multiple roles as earlier light infantry. Their arms were no lighter than line infantry; they were distinguished by their skirmish formation and flexible tactics.[citation needed]

The modern rifleman infantry became the primary force for taking and holding ground on battlefields as an element of combined arms. As firepower continued to increase, use of infantry lines diminished, until all infantry became light infantry in practice. Modern classifications of infantry have since expanded to reflect modern equipment and tactics, such as motorised infantry, mechanised or armoured infantry, mountain infantry, marine infantry, and airborne infantry.[citation needed]

Equipment

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

Beyond main arms and armour, an infantryman's "military kit" generally includes combat boots, battledress or combat uniform, camping gear, heavy weather gear, survival gear, secondary weapons and ammunition, weapon service and repair kits, health and hygiene items, mess kit, rations, filled water canteen, and all other consumables each infantryman needs for the expected duration of time operating away from their unit's base, plus any special mission-specific equipment. One of the most valuable pieces of gear is the entrenching tool—basically a folding spade—which can be employed not only to dig important defences, but also in a variety of other daily tasks, and even sometimes as a weapon.[11] Infantry typically have shared equipment on top of this, like tents or heavy weapons, where the carrying burden is spread across several infantrymen. In all, this can reach 25–45 kg (60–100 lb) for each soldier on the march.[12] Such heavy infantry burdens have changed little over centuries of warfare; in the late Roman Republic, legionaries were nicknamed "Marius' mules" as their main activity seemed to be carrying the weight of their legion around on their backs, a practice that predates the eponymous Gaius Marius.[13]

When combat is expected, infantry typically switch to "packing light", meaning reducing their equipment to weapons, ammunition, and other basic essentials, and leaving other items deemed unnecessary with their transport or baggage train, at camp or rally point, in temporary hidden caches, or even (in emergencies) simply discarding the items.[14] Additional specialised equipment may be required, depending on the mission or to the particular terrain or environment, including satchel charges, demolition tools, mines, or barbed wire, carried by the infantry or attached specialists.

Historically, infantry have suffered high casualty rates from disease, exposure, exhaustion and privation — often in excess of the casualties suffered from enemy attacks.[15] Better infantry equipment to support their health, energy, and protect from environmental factors greatly reduces these rates of loss, and increase their level of effective action. Health, energy, and morale are greatly influenced by how the soldier is fed, so militaries issue standardised field rations that provide palatable meals and enough calories to keep a soldier well-fed and combat-ready.[citation needed]

Communications gear has become a necessity, as it allows effective command of infantry units over greater distances, and communication with artillery and other support units. Modern infantry can have GPS, encrypted individual communications equipment, surveillance and night vision equipment, advanced intelligence and other high-tech mission-unique aids.[citation needed]

Armies have sought to improve and standardise infantry gear to reduce fatigue for extended carrying, increase freedom of movement, accessibility, and compatibility with other carried gear, such as the American all-purpose lightweight individual carrying equipment (ALICE).[citation needed]

Weapons

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

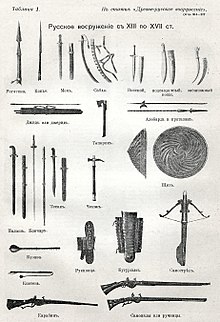

Infantrymen are defined by their primary arms – the personal weapons and body armour for their own individual use. The available technology, resources, history, and society can produce quite different weapons for each military and era, but common infantry weapons can be distinguished in a few basic categories.[16][17]

- Ranged combat weapons: javelins, slings, blowguns, bows, crossbows, hand cannons, arquebuses, muskets, grenades, flamethrowers.[17]

- Melee combat weapons: bludgeoning weapons like clubs, flails and maces; bladed weapons like swords, daggers, and axes; polearms like spears, halberds, naginata, and pikes.[17]

- Both ranged and close weapons: the bayonet fixed to a firearm allows infantrymen to use the same weapon for both ranged combat and close combat. This started with muskets and its use still continues with modern assault rifles.[17] Use of the bayonet has declined with the introduction of automatic firearms, but are still generally kept as a weapon of last resort.[18]

Infantrymen often carry secondary or back-up weapons, sometimes called a sidearm or ancillary weapons. Infantry with ranged or polearms often carried a sword or dagger for possible hand-to-hand combat.[16] The pilum was a javelin the Roman legionaries threw just before drawing their primary weapon, the gladius (short sword), and closing with the enemy line.[19]

Modern infantrymen now treat the bayonet as a backup weapon, but may also have handguns as sidearms. They may also deploy anti-personnel mines, booby traps, incendiary, or explosive devices defensively before combat.[citation needed]

Protection

[edit]

Infantry have employed many different methods of protection from enemy attacks, including various kinds of armour and other gear, and tactical procedures.

The most basic is personal armour. This includes shields, helmets and many types of armour – padded linen, leather, lamellar, mail, plate, and kevlar. Initially, armour was used to defend both from ranged and close combat; even a fairly light shield could help defend against most slings and javelins, though high-strength bows and crossbows might penetrate common armour at very close range. Infantry armour had to compromise between protection and coverage, as a full suit of attack-proof armour would be too heavy to wear in combat.[citation needed]

As firearms improved, armour for ranged defence had to be made thicker and heavier, which hindered mobility. With the introduction of the heavy arquebus designed to pierce standard steel armour, it was proven easier to make heavier firearms than heavier armour; armour transitioned to be only for close combat purposes. Pikemen armour tended to be just steel helmets and breastplates, and gunners had very little or no armour at all. By the time of the musket, the dominance of firepower shifted militaries away from any close combat, and use of armour decreased, until infantry typically went without wearing any armour.[citation needed]

Helmets were added back during World War I as artillery began to dominate the battlefield, to protect against their fragmentation and other blast effects beyond a direct hit. Modern developments in bullet-proof composite materials like kevlar have started a return to body armour for infantry, though the extra weight is a notable burden.[citation needed]

In modern times, infantrymen must also often carry protective measures against chemical and biological attack, including military gas masks, counter-agents, and protective suits. All of these protective measures add to the weight an infantryman must carry, and may decrease combat efficiency.[citation needed]

Infantry-served weapons

[edit]Early crew-served weapons were siege weapons, like the ballista, trebuchet, and battering ram. Modern versions include machine guns, anti-tank missiles, and infantry mortars.[citation needed]

Formations

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

Beginning with the development the first regular military forces, close-combat regular infantry fought less as unorganised groups of individuals and more in coordinated units, maintaining a defined tactical formation during combat, for increased battlefield effectiveness; such infantry formations and the arms they used developed together, starting with the spear and the shield.[citation needed]

A spear has decent attack abilities with the additional advantage keeping opponents at distance; this advantage can be increased by using longer spears, but this could allow the opponent to side-step the point of the spear and close for hand-to-hand combat where the longer spear is near useless. This can be avoided when each spearman stays side by side with the others in close formation, each covering the ones next to him, presenting a solid wall of spears to the enemy that they cannot get around.[citation needed]

Similarly, a shield has decent defence abilities, but is literally hit-or-miss; an attack from an unexpected angle can bypass it completely. Larger shields can cover more, but are also heavier and less manoeuvrable, making unexpected attacks even more of a problem. This can be avoided by having shield-armed soldiers stand close together, side-by-side, each protecting both themselves and their immediate comrades, presenting a solid shield wall to the enemy.

The opponents for these first formations, the close-combat infantry of more tribal societies, or any military without regular infantry (so called "barbarians") used arms that focused on the individual – weapons using personal strength and force, such as larger swinging swords, axes, and clubs. These take more room and individual freedom to swing and wield, necessitating a more loose organisation. While this may allow for a fierce running attack (an initial shock advantage) the tighter formation of the heavy spear and shield infantry gave them a local manpower advantage where several might be able to fight each opponent.[citation needed]

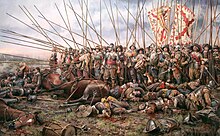

Thus tight formations heightened advantages of heavy arms, and gave greater local numbers in melee. To also increase their staying power, multiple rows of heavy infantrymen were added. This also increased their shock combat effect; individual opponents saw themselves literally lined-up against several heavy infantryman each, with seemingly no chance of defeating all of them. Heavy infantry developed into huge solid block formations, up to a hundred meters wide and a dozen rows deep.[citation needed]

Maintaining the advantages of heavy infantry meant maintaining formation; this became even more important when two forces with heavy infantry met in battle; the solidity of the formation became the deciding factor. Intense discipline and training became paramount. Empires formed around their military.[citation needed]

Organization

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

The organization of military forces into regular military units is first noted in Egyptian records of the Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BC). Soldiers were grouped into units of 50, which were in turn grouped into larger units of 250, then 1,000, and finally into units of up to 5,000 – the largest independent command. Several of these Egyptian "divisions" made up an army, but operated independently, both on the march and tactically, demonstrating sufficient military command and control organisation for basic battlefield manoeuvres. Similar hierarchical organizations have been noted in other ancient armies, typically with approximately 10 to 100 to 1,000 ratios (even where base 10 was not common), similar to modern sections (squads), companies, and regiments.[20]

Training

[edit]

The training of the infantry has differed drastically over time and from place to place. The cost of maintaining an army in fighting order and the seasonal nature of warfare precluded large permanent armies.[21]

The antiquity saw everything from the well-trained and motivated citizen armies of Greece and Rome, the tribal host assembled from farmers and hunters with only passing acquaintance with warfare and masses of lightly armed and ill-trained militia put up as a last ditch effort. Kushite king Taharqa enjoyed military success in the Near East as a result of his efforts to strengthen the army through daily training in long-distance running.[22]

In medieval times the foot soldiers varied from peasant levies to semi-permanent companies of mercenaries, foremost among them the Swiss, English, Aragonese and German, to men-at-arms who went into battle as well-armoured as knights, the latter of which at times also fought on foot.[citation needed]

The creation of standing armies—permanently assembled for war or defence—saw increase in training and experience. The increased use of firearms and the need for drill to handle them efficiently.[citation needed]

The introduction of national and mass armies saw an establishment of minimum requirements and the introduction of special troops (first of them the engineers going back to medieval times, but also different kinds of infantry adopted to specific terrain, bicycle, motorcycle, motorised and mechanised troops) culminating with the introduction of highly trained special forces during the first and second World War.[citation needed]

Air force and naval infantry

[edit]| NATO Map Symbol |

|---|

|

| Naval Infantry Company |

|

| Air Force Infantry Company |

Naval infantry, commonly known as marines, are primarily a category of infantry that form part of the naval forces of states and perform roles on land and at sea, including amphibious operations, as well as other, naval roles. They also perform other tasks, including land warfare, separate from naval operations.[citation needed]

Air force infantry and base defense forces are used primarily for ground-based defense of air bases and other air force facilities. They also have a number of other, specialist roles. These include, among others, Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) defence and training other airmen in basic ground defense tactics.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Air assault troops / Airborne forces

- Ashigaru

- Combined arms

- Foot guards

- Fusiliers

- Glider infantry / Paratrooper

- Grenadiers

- Indonesian Army infantry battalions

- Infantry Branch (United States)

- Infantry of the British Army

- Infantry tactics

- Line infantry

- Marines

- United States Army Rangers

- Riflemen

- Royal Canadian Infantry Corps

- School of Infantry

- Special forces / Commando

- Pathfinder (military)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]Infentory

- ^ "Infantry". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ "Infantryman". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ "Infantry". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ Kelly, Raymond (October 2005). "The evolution of lethal intergroup violence". PNAS. 102 (43): 24–29. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505955102. PMC 1266108. PMID 16129826.

- ^ Keeley, War Before Civilization, 1996, Oxford University Press, p. 45, Fig. 3.1

- ^ Newman, Simon (29 May 2012). "Military in the Middle Ages". thefinertimes.com. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (22 February 1994). "Remaking the Wheel: Evolution of the Chariot". The New York Times, Science. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Kagay, Donald J.; Villalon, L. J. Andrew (1999). The Circle of War in the Middle Ages. Boydell Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0851156453.

- ^ Carey, Brian Todd (2006). Warfare in the Medieval World. London: Pen & Sword Military. p. chapter 6. ISBN 978-1848847415.

- ^ Archer, Christon I. (2002). World History of Warfare. U of Nebraska Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0803219410.

- ^ "Military kit through the ages: from the Battle of Hastings to Helmand". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Murphy, Patricia. "Weight Of War: Soldiers' Heavy Gear Packs On Pain". NPR. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Taylor, Michael J (2019). "Tactical reform in the late Roman republic: the view from Italy". Historia. 68 (1): 76–94. doi:10.25162/historia-2019-0004. ISSN 0018-2311. S2CID 165437350.

- ^ Handy, Aaron Jr. (2010). "Part Two, chapter 3". That Powerless Feeling. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4251-3155-5.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (1989). Battle cry of freedom : the Civil War era (1st Ballantine books ed.). Ballantine Books. p. 485. ISBN 0345359429.

- ^ a b Zabecki, David T. (28 October 2014). Germany at War: 400 Years of Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 640. ISBN 978-1598849806.

- ^ a b c d Blumberg, Naomi. "List of weapons". Encyclopedia Britannica. The Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ Kontis, George. "Are We Forever Stuck with the Bayonet?". Small Arms Defense Journal. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ Zhmodikov, Alexander (2000). "Roman Republican Heavy Infantrymen in Battle (IV-II Centuries B.C.)". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. Vol. 49. ABC-CLIO. p. 640. ISBN 978-1598849806.

- ^ Centeno, Miguel A.; Enriquez, Elaine (31 March 2016). "Origins of Battle". War and Society. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 81–84. ISBN 978-0-313-22348-8.

- ^ "Training of Infantry in history". Bing. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Török, László (1998). The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Leiden: Brill. pp. 132–133, 153–184. ISBN 90-04-10448-8.

Sources

[edit]- English, John A., Gudmundsson, Bruce I., On Infantry, (Revised edition), The Military Profession series, Praeger Publishers, London, 1994. ISBN 0-275-94972-9.

- The Times, Earl Wavell, Thursday, 19 April 1945 In Praise of Infantry Archived 16 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- Tobin, James, Ernie Pyle's War: America's Eyewitness to World War II, Free Press, 1997.

- Mauldin, Bill, Ambrose, Stephen E., Up Front, W. W. Norton, 2000.

- Trogdon, Robert W., Ernest Hemingway: A Literary Reference, Da Capo Press, 2002.

- The New York Times, Maj Gen C T Shortis, British Director of Infantry, 4 February 1985.

- Heinl, Robert Debs, Dictionary of Military and Naval Quotations, Plautus in The Braggart Captain (3rd century AD), Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1978.

- Nafziger, George, Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, Presidio Press, 1998.

- McManus, John C. Grunts: inside the American infantry combat experience, World War II through Iraq New York, NY: NAL Caliber. 2010 ISBN 978-0-451-22790-4 plus Webcast Author Lecture at the Pritzker Military Library on 29 September 2010.

External links

[edit]- Historic films and photos showing Infantries in World War I at europeanfilmgateway.eu

- In Praise of Infantry, by Field-Marshal Earl Wavell; First published in "The Times", Thursday, 19 April 1945.

- The Lagunari "Serenissima" Regiment KFOR: KFOR Chronicle.

- Web Version of U.S. Army Field Manual 3–21.8 – The Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 517–533. — includes several drawings