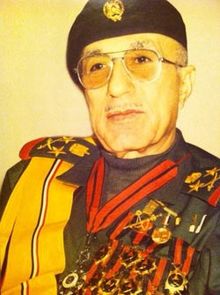

Hussein Rashid

Colonel General Hussein Rashid Mohammed al-Tikriti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | حسين رشيد محمد التكريتي |

| Born | January 1, 1940 Khezamia, Tikrit, Kingdom of Iraq |

| Conviction(s) | War crimes Crimes against humanity |

| Criminal penalty | Death; commuted to life imprisonment |

| Allegiance | (1968–2003) |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1962–2003 |

| Rank | |

| Battles / wars | |

Hussein Rashid Mohammed al-Tikriti (Arabic: حسين رشيد محمد التكريتي; 1 January 1940) is an Iraqi former military officer who formerly served as the Chief of the General Staff of the Iraqi Armed Forces under the rule of Saddam Hussein.

A fierce loyalist to Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, Rashid was also a tough and competent general.[1] Middle Eastern military and political affairs analyst Kenneth M. Pollack listed Rashid as an example of Arab generals in recent decades who had proven to be "first-rate generals", listing him alongside Syria's Ali Aslan and Jordan's Zaid ibn Shaker.[2]

Early life

[edit]Hussein is a Arabized Kurd[3] and was born in the town of Khezamia, near Tikrit, in 1940. He received his primary and secondary education in Tikrit.

Military career

[edit]Hussein joined the military, and graduated from the Iraqi Military Academy in 1962 with a Bachelor's in military science. He graduated from the Iraqi Joint Staff College in 1968 with a master's degree in military science. He also later received a PhD in the same field.

Iran–Iraq War

[edit]In September 1980, Iraqi forces launched an invasion of southern Iran. Though initially successful, in 1981 Iran launched a counteroffensive, and by 1982 had regained most of the territory lost. In July 1982, Iran invaded southern Iraq, targeting the city of Basra.[4]

During the first two years of the war with Iran, Saddam Hussein began to promote competent commanders over and against those who merely served as political cronies. Among these included Rashid.[5] Rashid was authorized to expand the Republican Guard to the size of an armored division.[6] During his early years of command, the Guard would be expanded to 16 brigades of 30,000 men,[7] and by 1988 the Republican Guard had reached the size of 25 brigades and a total manpower of 103,000 men. Although Saddam Hussein was the nominal commander, Rashid was the actual commander on the ground, albeit reporting directly to Saddam.[8]

Rashid was later in charge of the successful counter-offensives in 1988.[9][10] Regarding operations within Kurdistan, Rashid desired a greater emphasis on this part of the campaign, and noted that the Iranians held an advantage in small covert units due to the northern region being "ideal for this type of operation". However, Saddam wished to focus on the southern front of the country, in order to convey to the Iranians that their goal of taking Basra was an impossibility.[11]

It was during the Anfal Campaign between 1987 and 1988 that Rashid was accused, along with many other generals, for crimes against humanity against the Kurdish populations, with over 182,000 Kurdish men, women, and children murdered, partially with chemical weapons.[12][13]

In July 1988, with Iraq continually making territorial gains, Iran and Iraq agreed to accept a United Nations-brokered ceasefire under Security Council Resolution 598. The war ended formally on 20 August 1988.[4]

Gulf War

[edit]Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, and tensions mounted through 1991. Shortly after the invasion, Rashid was appointed by Saddam Hussein as the new Iraqi Army Chief of Staff, after Hussein had fired the previous one.[14][10]

On 24 February, the ground attack of the Coalition began. At 8:30 PM on 25 February, Rashid received a phone call from Saddam ordering the army to retreat from Kuwait. Saddam told Rashid, "I don't want our Army to panic. Our soldiers do not like humiliation; they like to uphold their pride."[15] By 26 February, Iraqi forces had fled Kuwait City.

The performance by Rashid and his staff during the war was seen by analyst Pollack as a "very creditable performance given what they had to work with", but that the error fell on Hussein and his insistence to fight the coalition rather than negotiate a way out of Kuwait.[16]

Post Gulf War period

[edit]After the war, Rashid was removed from his position as Chief of Staff,[17] afterward once again made commander of the Republican Guard,[18] and served as a special military advisor to Saddam Hussein.[19]

Rashid was involved in the suppression of the 1991 Shi'i uprising, for which he would later be accused of war crimes.[20]

2003 invasion of Iraq

[edit]By 2003, Rashid was secretary-general of the Armed Forces Command, and part of Saddam Hussein's "inner circle" that planned a defense in the face of a potential attack from the United States and her allies.[20]

Iraqi Special Tribunal

[edit]Following the invasion, Hussein was one of several individuals indicted by the Iraqi Special Tribunal for war crimes. Specifically Hussein was charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity relating to possible war crimes carried out against the Kurds during the al-Anfal campaign in 1988.[21] At the time of the campaign Hussein was serving as Deputy Chief of Staff of the Iraqi Armed Forces.[22]

The trial began on 21 August 2006 and concluded on 24 June 2007, with Hussein, alongside several others, being found guilty and sentenced to death for war crimes and crimes against humanity.[21] In total Hussein was sentenced to three death sentences.[22] After his sentence was read out Hussein, alongside fellow former General Sultan Hashim Ahmad al-Tai, spoke out. As a result, the chief judge, Mohammed Ureibi al-Khalifa, ordered that they should be quickly removed from the court. Hussein reportedly shouted "Thanks be to God, we are being executed because we defended our country against thieves and criminals. We defended Iraq."[22]

On 3 October 2007 the Iraqi authorities decided to postpone the date of Rashid's execution. On 28 February 2008 a three-member Iraqi Presidential Council agreed to the execution of Ali Hassan al-Majid, however did not approve of the execution of either Hussein or Sultan Hashim Ahmad al-Tai.[21] The Council reportedly argued that Tai and Hussein should not be executed as, being military personnel at the time, they were merely following orders.[23]

On 2 December 2008 Hussein was given a further life sentence for his role in the 1991 uprising in Iraq.[23]

On 14 July 2011 Hussein, along with numerous other former high-ranking officials, were transferred from US to Iraqi custody. Hussein had been being detained at Camp Cropper near Baghdad International Airport. Following the transfer several Iraqi lawmakers renewed their calls on the Presidency to not approve the executions. President Talabani had authorized his Shi'ite Vice President Khudair al-Khuzaie to sign the verdict.[24]

Personal life

[edit]Hussein is married, and has three children.

References

[edit]- ^ Jerrold, M. Post (2004). Leaders and Their Followers in a Dangerous World: The Psychology of Political Behavior. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 220. ISBN 9780801441691. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Pollack, Kenneth M. (2019). Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780190906962. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Michael Eisenstadt, Like a Phoenix from the Ashes?: The Future of Iraqi Military Power. Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1993. p. 86: “...succeeded Husayn Rashid Muhammad al-Tikriti, an Arabized Kurd.”[1]

- ^ a b "Iran-Iraq War". History.com. The Arena Group. 13 July 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Pollack, Kenneth M. (2019). Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780190906962. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Satloff, Robert B. (2019). The Politics Of Change In The Middle East. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000304664. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Antal, John F. (1990). "The Sword of Saddam: An Overview of the Iraqi Armed Forces". Armor. 99 (6): 11. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ McNab, Chris (2022). Armies of the Iran–Iraq War 1980–88. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 9781472845559. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Leitner, Peter M. (2007). Unheeded Warnings: The Lost Reports of The Congressional Task Force on Terrorism and Unconventional Warfare, Volume 2: The Perpetrators and the Middle East. Washington: Crossbow Books. p. 227. ISBN 9780979223679. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ a b Pollack, Kenneth M. (2019). Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 158. ISBN 9780190906962. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Woods, Kevin M.; Murray, Williamson (2014). The Iran-Iraq War: A Military and Strategic History. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 325. ISBN 9781107062290. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Woods, Kevin M.; Murray, Williamson; Elkhamri, Mounir; Holaday, Thomas (2009). Saddam's War: An Iraqi Military Perspective of the Iran-Iraq War. NDU Press. p. 140.

- ^ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2008 Vol.1. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. December 2010. p. 1894. ISBN 9780160875151. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Palkki, David D.; Woods, Kevin M.; Stout, Mark E., eds. (2011). The Saddam Tapes: The Inner Workings of a Tyrant's Regime, 1978–2001. United States: Cambridge University Press. p. xvi. ISBN 978-1139505468. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Fontenot, Gregory (2017). The 1st Infantry Division and the U.S. Army transformed : road to victory in Desert Storm 1970–1991. Baltimore, Maryland: University of Missouri Press. p. 306. ISBN 9780826273765. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Pollack, Kenneth M. (2019). Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780190906962. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim; Rautsi, Inari (2002). Saddam Hussein: A Political Biography. United States: Grove Press. p. 273. ISBN 9780802139788. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Cordesman, Anthony H. (2018). Iraq: Sanctions And Beyond. Routledge. ISBN 978-0429968181. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ The Situation in Iraq Hearing Before the Committee on Armed Services, United States Senate, One Hundred Fourth Congress, Second Session, September 12, 1996 · Volume 4. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1996. p. 46. ISBN 9780160541711. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ a b Dougherty, Beth (2019). Historical Dictionary of Iraq. United States: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 614. ISBN 9781538120057. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ a b c "TRIAL : Profiles". Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Burns, John F. (25 June 2007). "Hussein Cousin Sentenced to Die for Kurd Attacks". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ a b "Turkmenistan". Amnesty.org. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ "Iraqi lawmakers against execution of top officials in Saddam regime". News.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- 1940 births

- Iraqi generals

- Iraqi Military Academy alumni

- Iraqi military personnel of the Iran–Iraq War

- Iraqi people convicted of war crimes

- Iraqi people convicted of crimes against humanity

- Iraqi prisoners sentenced to death

- Iraqi Sunni Muslims

- Kurdish genocide perpetrators

- Military leaders of the Iraq War

- Living people

- People from Tikrit

- Iraqi people of the Yom Kippur War

- Prisoners sentenced to death by Iraq