History of Python

This article is missing information about prominent features of versions after 3.0. (March 2024) |

The programming language Python was conceived in the late 1980s,[1] and its implementation was started in December 1989[2] by Guido van Rossum at CWI in the Netherlands as a successor to ABC capable of exception handling and interfacing with the Amoeba operating system.[3] Van Rossum is Python's principal author, and his continuing central role in deciding the direction of Python is reflected in the title given to him by the Python community, Benevolent Dictator for Life (BDFL).[4][5] (However, Van Rossum stepped down as leader on July 12, 2018.[6]). Python was named after the BBC TV show Monty Python's Flying Circus.[7]

Python 2.0 was released on October 16, 2000, with many major new features, including a cycle-detecting garbage collector (in addition to reference counting) for memory management and support for Unicode, along with a change to the development process itself, with a shift to a more transparent and community-backed process.[8]

Python 3.0, a major, backwards-incompatible release, was released on December 3, 2008[9] after a long period of testing. Many of its major features have also been backported to the backwards-compatible, though now-unsupported, Python 2.6 and 2.7.[10]

Early history

[edit]In February 1991, Van Rossum published the code (labeled version 0.9.0) to alt.sources.[11][12] Already present at this stage in development were classes with inheritance, exception handling, functions, and the core datatypes of list, dict, str and so on. Also in this initial release was a module system borrowed from Modula-3; Van Rossum describes the module as "one of Python's major programming units".[1] Python's exception model also resembles Modula-3's, with the addition of an else clause.[3] In 1994 comp.lang.python, the primary discussion forum for Python, was formed, marking a milestone in the growth of Python's userbase and popularity.[1]

Version 1

[edit]Python reached version 1.0 in January 1994. The major new features included in this release were the functional programming tools lambda, map, filter and reduce. Van Rossum stated that "Python acquired lambda, reduce(), filter() and map(), courtesy of a Lisp hacker who missed them and submitted working patches".[13]

The last version released while Van Rossum was at CWI was Python 1.2. In 1995, Van Rossum continued his work on Python at the Corporation for National Research Initiatives (CNRI) in Reston, Virginia from where he released several versions.

By version 1.4, Python had acquired several new features. Notable among these are the Modula-3 inspired keyword arguments (which are also similar to Common Lisp's keyword arguments) and built-in support for complex numbers. Also included is a basic form of data hiding by name mangling, though this is easily bypassed.[14]

During Van Rossum's stay at CNRI, he launched the Computer Programming for Everybody (CP4E) initiative, intending to make programming more accessible to more people, with a basic "literacy" in programming languages, similar to the basic English literacy and mathematics skills required by most employers. Python served a central role in this: because of its focus on clean syntax, it was already suitable, and CP4E's goals bore similarities to its predecessor, ABC. The project was funded by DARPA.[15] As of 2007[update], the CP4E project is inactive, and while Python attempts to be easily learnable and not too arcane in its syntax and semantics, outreach to non-programmers is not an active concern.[16]

BeOpen

[edit]In 2000, the Python core development team moved to BeOpen.com[17] to form the BeOpen PythonLabs team.[18][19] CNRI requested that a version 1.6 be released, summarizing Python's development up to the point at which the development team left CNRI. Consequently, the release schedules for 1.6 and 2.0 had a significant amount of overlap.[8] Python 2.0 was the only release from BeOpen.com. After Python 2.0 was released by BeOpen.com, Guido van Rossum and the other PythonLabs developers joined Digital Creations.

The Python 1.6 release included a new CNRI license that was substantially longer than the CWI license that had been used for earlier releases. The new license included a clause stating that the license was governed by the laws of the State of Virginia. The Free Software Foundation argued that the choice-of-law clause was incompatible with the GNU General Public License. BeOpen, CNRI and the FSF negotiated a change to Python's free-software license that would make it GPL-compatible. Python 1.6.1 is essentially the same as Python 1.6, with a few minor bug fixes, and with the new GPL-compatible license.[20]

Version 2

[edit]Python 2.0, released October 2000,[8] introduced list comprehensions, a feature borrowed from the functional programming languages SETL and Haskell. Python's syntax for this construct is very similar to Haskell's, apart from Haskell's preference for punctuation characters and Python's preference for alphabetic keywords. Python 2.0 also introduced a garbage collector able to collect reference cycles.[8]

Python 2.1 was close to Python 1.6.1, as well as Python 2.0. Its license was renamed Python Software Foundation License. All code, documentation and specifications added, from the time of Python 2.1's alpha release on, is owned by the Python Software Foundation (PSF), a nonprofit organization formed in 2001, modeled after the Apache Software Foundation.[20] The release included a change to the language specification to support nested scopes, like other statically scoped languages.[21] (The feature was turned off by default, and not required, until Python 2.2.)

Python 2.2 was released in December 2001;[22] a major innovation was the unification of Python's types (types written in C) and classes (types written in Python) into one hierarchy. This single unification made Python's object model purely and consistently object oriented.[23] Also added were generators which were inspired by Icon.[24]

Python 2.5 was released in September 2006[25] and introduced the with statement, which encloses a code block within a context manager (for example, acquiring a lock before the block of code is run and releasing the lock afterwards, or opening a file and then closing it), allowing resource acquisition is initialization (RAII)-like behavior and replacing a common try/finally idiom.[26]

Python 2.6 was released to coincide with Python 3.0, and included some features from that release, as well as a "warnings" mode that highlighted the use of features that were removed in Python 3.0.[27][10] Similarly, Python 2.7 coincided with and included features from Python 3.1,[28] which was released on June 26, 2009. Parallel 2.x and 3.x releases then ceased, and Python 2.7 was the last release in the 2.x series.[29] In November 2014, it was announced that Python 2.7 would be supported until 2020, but users were encouraged to move to Python 3 as soon as possible.[30] Python 2.7 support ended on January 1, 2020, along with code freeze of 2.7 development branch. A final release, 2.7.18, occurred on April 20, 2020, and included fixes for critical bugs and release blockers.[31] This marked the end-of-life of Python 2.[32]

Version 3

[edit]Python 3.0 (also called "Python 3000" or "Py3K") was released on December 3, 2008.[9] It was designed to rectify fundamental design flaws in the language – the changes required could not be implemented while retaining full backwards compatibility with the 2.x series, which necessitated a new major version number. The guiding principle of Python 3 was: "reduce feature duplication by removing old ways of doing things".[33]

Python 3.0 was developed with the same philosophy as in prior versions. However, as Python had accumulated new and redundant ways to program the same task, Python 3.0 had an emphasis on removing duplicative constructs and modules, in keeping with the Zen of Python: "There should be one— and preferably only one —obvious way to do it".

Nonetheless, Python 3.0 remained a multi-paradigm language. Coders could still follow object-oriented, structured, and functional programming paradigms, among others, but within such broad choices, the details were intended to be more obvious in Python 3.0 than they were in Python 2.x.

Compatibility

[edit]Python 3.0 broke backward compatibility, and much Python 2 code does not run unmodified on Python 3.[34] Python's dynamic typing combined with the plans to change the semantics of certain methods of dictionaries, for example, made perfect mechanical translation from Python 2.x to Python 3.0 very difficult. A tool called "2to3" does the parts of translation that can be done automatically. At this, 2to3 appeared to be fairly successful, though an early review noted that there were aspects of translation that such a tool would never be able to handle.[35] Prior to the roll-out of Python 3, projects requiring compatibility with both the 2.x and 3.x series were recommended to have one source (for the 2.x series), and produce releases for the Python 3.x platform using 2to3. Edits to the Python 3.x code were discouraged for so long as the code needed to run on Python 2.x.[10] This is no longer recommended; as of 2012 the preferred approach was to create a single code base that can run under both Python 2 and 3 using compatibility modules.[36]

Features

[edit]Some of the major changes included for Python 3.0 were:

- Changing

printso that it is a built-in function, not a statement. This made it easier to change a module to use a different print function, as well as making the syntax more regular. In Python 2.6 and 2.7print()is available as a builtin but is masked by the print statement syntax, which can be disabled by enteringfrom __future__ import print_functionat the top of the file[37] - Removal of the Python 2

inputfunction, and the renaming of theraw_inputfunction toinput. Python 3'sinputfunction behaves like Python 2'sraw_inputfunction, in that the input is always returned as a string rather than being evaluated as an expression - Moving

reduce(but notmaporfilter) out of the built-in namespace and intofunctools(the rationale being code that usesreduceis less readable than code that uses a for loop and accumulator variable)[38][39] - Adding support for optional function annotations that can be used for informal type declarations or other purposes[40]

- Unifying the

str/unicodetypes, representing text, and introducing a separate immutablebytestype; and a mostly corresponding mutablebytearraytype, both of which represent arrays of bytes[41] - Removing backward-compatibility features, including old-style classes, string exceptions, and implicit relative imports

- A change in integer division functionality: in Python 2, integer division always returns an integer. For example

5 / 2is2; whereas in Python 3,5 / 2is2.5. (In both Python 2 – 2.2 onwards – and Python 3, a separate operator exists to provide the old behavior:5 // 2is2) - Allowing non-ASCII letters to be used in identifiers,[42] such as in

smörgåsbord, fully supporting Unicode characters in source code (UTF-8 is used by default)

Subsequent releases in the Python 3.x series have included additional, substantial new features; all ongoing development of the language is done in the 3.x series.

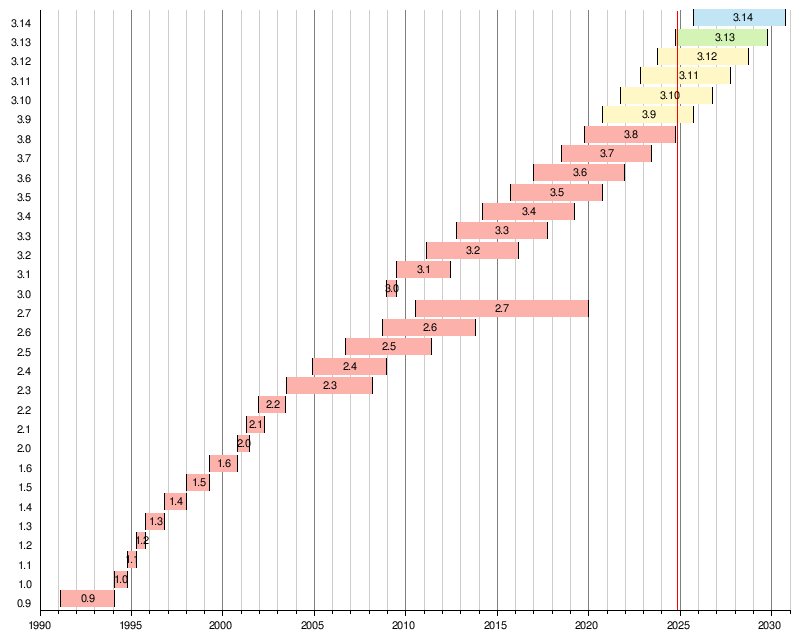

Table of versions

[edit]Releases before numbered versions:

- Implementation started – December, 1989[2]

- Internal releases at Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica – 1990[2]

| Version | Latest micro version |

Release date | End of full support | End of security fixes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9 | 0.9.9[2] | 1991-02-20[2] | 1993-07-29[a][2] | |

| 1.0 | 1.0.4[2] | 1994-01-26[2] | 1994-02-15[a][2] | |

| 1.1 | 1.1.1[2] | 1994-10-11[2] | 1994-11-10[a][2] | |

| 1.2 | 1995-04-13[2] | Unsupported | ||

| 1.3 | 1995-10-13[2] | Unsupported | ||

| 1.4 | 1996-10-25[2] | Unsupported | ||

| 1.5 | 1.5.2[43] | 1998-01-03[2] | 1999-04-13[a][2] | |

| 1.6 | 1.6.1[43] | 2000-09-05[44] | 2000–09[a][43] | |

| 2.0 | 2.0.1[45] | 2000-10-16[46] | 2001-06-22[a][45] | |

| 2.1 | 2.1.3[45] | 2001-04-15[47] | 2002-04-09[a][45] | |

| 2.2 | 2.2.3[45] | 2001-12-21[48] | 2003-05-30[a][45] | |

| 2.3 | 2.3.7[45] | 2003-06-29[49] | 2008-03-11[a][45] | |

| 2.4 | 2.4.6[45] | 2004-11-30[50] | 2008-12-19[a][45] | |

| 2.5 | 2.5.6[45] | 2006-09-19[51] | 2011-05-26[a][45] | |

| 2.6 | 2.6.9[27] | 2008-10-01[27] | 2010-08-24[b][27] | 2013-10-29[27] |

| 2.7 | 2.7.18[32] | 2010-07-03[32] | 2020-01-01[c][32] | |

| 3.0 | 3.0.1[45] | 2008-12-03[27] | 2009-06-27[52] | |

| 3.1 | 3.1.5[53] | 2009-06-27[53] | 2011-06-12[54] | 2012-04-06[53] |

| 3.2 | 3.2.6[55] | 2011-02-20[55] | 2013-05-13[b][55] | 2016-02-20[55] |

| 3.3 | 3.3.7[56] | 2012-09-29[56] | 2014-03-08[b][56] | 2017-09-29[56] |

| 3.4 | 3.4.10[57] | 2014-03-16[57] | 2017-08-09[58] | 2019-03-18[a][57] |

| 3.5 | 3.5.10[59] | 2015-09-13[59] | 2017-08-08[60] | 2020-09-30[59] |

| 3.6 | 3.6.15[61] | 2016-12-23[61] | 2018-12-24[b][61] | 2021-12-23[61] |

| 3.7 | 3.7.17[62] | 2018-06-27[62] | 2020-06-27[b][62] | 2023-06-06[62] |

| 3.8 | 3.8.20[63] | 2019-10-14[63] | 2021-05-03[b][63] | 2024-10-07[63] |

| 3.9 | 3.9.20[64] | 2020-10-05[64] | 2022-05-17[b][64] | 2025-10[64][65] |

| 3.10 | 3.10.15[66] | 2021-10-04[66] | 2023-04-05[b][66] | 2026-10[66] |

| 3.11 | 3.11.10[67] | 2022-10-24[67] | 2024-04-02[b][67] | 2027-10[67] |

| 3.12 | 3.12.7[68] | 2023-10-02[68] | 2025-05[68] | 2028-10[68] |

| 3.13 | 3.13.0[69] | 2024-10-07[69] | 2026-05[69] | 2029-10[69] |

| 3.14 | 3.14.0a1[70] | 2025-10-01[70] | 2027-05[70] | 2030-10[70] |

Table notes:

Support

[edit]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "The Making of Python". Artima Developer. Archived from the original on September 1, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q van Rossum, Guido (January 20, 2009). "A Brief Timeline of Python". Archived from the original on August 25, 2011. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ a b "Why was Python created in the first place?". Python FAQ. Archived from the original on February 23, 2008. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ van Rossum, Guido (July 31, 2008). "Origin of BDFL". Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ "Python Creator Scripts Inside Google". www.eweek.com. March 7, 2006. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ^ Fairchild, Carlie (July 12, 2018). "Guido van Rossum Stepping Down from Role as Python's Benevolent Dictator For Life". Linux Journal. Archived from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ "General Python FAQ — Python 3.8.3 documentation". docs.python.org. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Kuchling, Andrew M.; Zadka, Moshe. "What's New in Python 2.0". Archived from the original on December 14, 2009. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ a b "Welcome to Python.org". python.org. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ a b c van Rossum, Guido (April 5, 2006). "PEP 3000 – Python 3000". Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ "Python 0.9.1 part 01/21". alt.sources archives. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ "HISTORY". Python source distribution. Python Foundation. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- ^ van Rossum, Guido. "The fate of reduce() in Python 3000". Artima Developer. Archived from the original on April 7, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ "LJ #37: Python 1.4 Update". Archived from the original on May 1, 2007. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ van Rossum, Guido. "Computer Programming for Everybody". Archived from the original on May 1, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ "Computer Programming for Everybody". Python Software Foundation. Archived from the original on March 29, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ "Python Development Team Moves to BeOpen.Com – Slashdot". slashdot.org. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ "Open | Your digital insurance partner". Archived from the original on August 15, 2000.

- ^ "Content Management Provider PyBiz Announces Strategic Partnership With BeOpen in Utilizing Python Programming Language" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ a b "History and License". Python 3 Documentation. Archived from the original on December 5, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ Hylton, Jeremy (November 1, 2000). "PEP 227 – Statically Nested Scopes". Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ "Python 2.2". Python.org. Archived from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Kuchling, Andrew M. (December 21, 2001). "PEPs 252 and 253: Type and Class Changes". What's New in Python 2.2. Python Foundation. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ Schemenauer, Neil; Peters, Tim; Hetland, Magnus (December 21, 2001). "PEP 255 – Simple Generators". Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ "Python 2.5 Release". Python.org. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Highlights: Python 2.5". Python.org. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Norwitz, Neal; Warsaw, Barry (June 29, 2006). "PEP 361 – Python 2.6 and 3.0 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Kuchling, Andrew M. (July 3, 2010). "What's New in Python 2.7". Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

Much as Python 2.6 incorporated features from Python 3.0, version 2.7 incorporates some of the new features in Python 3.1. The 2.x series continues to provide tools for migrating to the 3.x series.

- ^ Warsaw, Barry (November 9, 2011). "PEP 404 – Python 2.8 Un-release Schedule". Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ Gee, Sue (April 14, 2014). "Python 2.7 To Be Maintained Until 2020". i-programmer.info. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ "Commits: python/cpython at 2.7". GitHub. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Peterson, Benjamin (November 3, 2008). "PEP 373 – Python 2.7 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ "PEP 3100 – Miscellaneous Python 3.0 Plans | peps.python.org". peps.python.org. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ "PEP 3000 – Python 3000 | peps.python.org". peps.python.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Ruby, Sam (September 1, 2007). "2to3". intertwingly.net. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ Coghlan, Alyssa (April 21, 2020). "Python 3 Q & A – Alyssa Coghlan's Python Notes". python-notes.curiousefficiency.org. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brandl, Georg (November 19, 2007). "PEP 3105 – Make print a function". Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ van Rossum, Guido. "Python 3000 FAQ". artima.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ "The fate of reduce() in Python 3000". www.artima.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Winter, Collin; Lownds, Tony (December 2, 2006). "PEP 3107 – Function Annotations". Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ van Rossum, Guido (September 26, 2007). "PEP 3137 – Immutable Bytes and Mutable Buffer". Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ "PEP 3131 – Supporting Non-ASCII Identifiers | peps.python.org". Python Enhancement Proposals (PEPs). Retrieved July 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Releases | Python.org". Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Drake, Fred L. Jr. (July 25, 2000). "PEP 160 – Python 1.6 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Download Python | Python.org". Archived from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Hylton, Jeremy. "PEP 200 – Python 2.0 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Hylton, Jeremy (October 16, 2000). "PEP 226 – Python 2.1 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Warsaw, Barry; van Rossum, Guido (April 17, 2001). "PEP 251 – Python 2.2 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ van Rossum, Guido (February 27, 2002). "PEP 283 – Python 2.3 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Warsaw, Barry; Hettinger, Raymond; Baxter, Anthony (July 29, 2003). "PEP 320 – Python 2.4 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Norwitz, Neal; van Rossum, Guido; Baxter, Anthony (February 7, 2006). "PEP 356 – Python 2.5 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ "17. Development Cycle — Python Developer's Guide". Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c Peterson, Benjamin (February 8, 2009). "PEP 375 – Python 3.1 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on April 19, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Peterson, Benjamin (June 12, 2011). "[RELEASED] Python 3.1.4". python-announce (Mailing list). Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Brandl, Georg (December 30, 2009). "PEP 392 – Python 3.2 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on April 19, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Brandl, Georg (March 23, 2011). "PEP 398 – Python 3.3 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c Hastings, Larry (October 17, 2012). "PEP 429 – Python 3.4 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Hastings, Larry (August 9, 2017). "[RELEASED] Python 3.4.7 is now available". python-announce (Mailing list). Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c Hastings, Larry (September 22, 2014). "PEP 478 – Python 3.5 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ^ Hastings, Larry (August 8, 2017). "[RELEASED] Python 3.5.4 is now available". python-announce (Mailing list). Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Deily, Ned (May 30, 2015). "PEP 494 – Python 3.6 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Deily, Ned (December 23, 2016). "PEP 537 – Python 3.7 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Langa, Łukasz (January 27, 2018). "PEP 569 – Python 3.8 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Langa, Łukasz (October 13, 2020). "PEP 596 – Python 3.9 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ Langa, Łukasz (June 4, 2019). "PEP 602 – Annual Release Cycle for Python". Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Salgado, Pablo (May 25, 2020). "PEP 619 – Python 3.10 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Salgado, Pablo (July 12, 2021). "PEP 664 – Python 3.11 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Wouters, Thomas (May 24, 2022). "PEP 693 – Python 3.12 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Wouters, Thomas (May 26, 2023). "PEP 719 – Python 3.13 Release Schedule". Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d van Kemenade, Hugo (April 24, 2024). "PEP 745 – Python 3.14 Release Schedule | peps.python.org". Python Enhancement Proposals (PEPs). Archived from the original on May 5, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.