Skate (fish)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

| Skates Temporal range: [1]

| |

|---|---|

| |

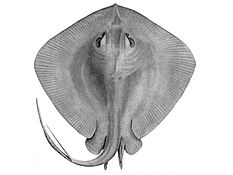

| Arctic skate, Amblyraja hyperborea | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Rajiformes |

| Family: | Rajidae Bonaparte, 1831 |

Skates are cartilaginous fish belonging to the family Rajidae in the superorder Batoidea of rays. More than 150 species have been described, in 17 genera.[2] Softnose skates and pygmy skates were previously treated as subfamilies of Rajidae (Arhynchobatinae and Gurgesiellinae), but are now considered as distinct families.[2] Alternatively, the name "skate" is used to refer to the entire order of Rajiformes (families Anacanthobatidae, Arhynchobatidae, Gurgesiellidae and Rajidae).[2]

Members of Rajidae are distinguished by a stiff snout and a rostrum that is not reduced.[3][4]

Taxonomy and systematics

[edit]Evolution

[edit]Skates belong to the ancient lineage of cartilaginous fishes. Fossil denticles (tooth-like scales in the skin) resembling those of today's chondrichthyans date at least as far back as the Ordovician, with the oldest unambiguous fossils of cartilaginous fish dating from the middle Devonian. A clade within this diverse family, the Neoselachii, emerged by the Triassic, with the best-understood neoselachian fossils dating from the Jurassic. This clade is represented today by sharks, sawfish, rays and skates.[5]

The body plan of skates is caused by skate-specific genomic rearrangements that have altered the three-dimensional regulatory landscape of genes. These changes arose about 286–221 million years ago when skates diverged from sharks.[6]

Classification

[edit]The skate belongs to the class Chondrichthyes. This class consists of all the cartilaginous fishes, including sharks and stingrays. Chondrichthyes is divided into two subclasses; of which Elasmobranchii includes skates, rays, and sharks. Skates are the most diverse elasmobranch group, comprising over 20% of the known species. The number of species is likely to increase as taxonomic issues are resolved and new species are identified.[7] Thefollowing genera recognized in the family Rajidae:[8]

- Amblyraja Malm, 1877

- Beringraja Ishihara, Treloar, Bor, Senou & Jeong, 2012

- Breviraja Bigelow & Schroeder, 1948

- Caliraja Ebert, 2022

- Dactylobatus Bean & Weed, 1909

- Dentiraja Whitley, 1940

- Dipturus Rafinesque, 1810

- Hongeo Jeong & Nakabo, 2009

- Leucoraja Malm, 1877

- Malacoraja Stehmann, 1970

- Neoraja McEachran & Compagno, 1982

- Okamejei Ishiyama, 1958

- Orbiraja Last, Weigmann & Dumale, 2016

- Raja Linnaeus, 1758

- Rajella Stehmann, 1970

- Rostroraja Hulley, 1972

- Spiniraja Whitley, 1939

- Zearaja Whitley 1939

Skates have more valid species than any other group of cartilaginous fishes.[citation needed] Since 1950, 126 new species of skates have been discovered. Five scientists take credit for the rapid increase of findings.[citation needed] The Rajidae are considered monophyletic because of their similarity in appearance. There are 18 genera[8] and about 250 valid species. However, there is little information about the diets of about 24% of these species. There are at least 45 dubious species of skates worldwide.[9]

Description

[edit]General Batoidea characteristics

[edit]Skates are cartilaginous fishes like other Chondrichthyes, however, skates, like rays and other Rajiformes, have a flat body shape with flat pectoral fins that extend the length of their body.[10] This structure creates power for forward propulsion, providing the emergence swimming capabilities that enabled skates to colonize the sea floor.[6]

A large portion of the skate's dorsal body is covered by rough skin made of placoid scales. Placoid scales have a pointed tip that is oriented caudally and are homologous to teeth. Their mouths are located on the underside of the body, with a jaw suspension common to Batoids known as euhyostyly.[11] Skate's gill slits are located ventrally as well, but dorsal spiracles allow the skate to be partially buried in floor sediment and still complete respiratory exchange.[12] Also located on the dorsal side of the skate are their two eyes which allow for predator awareness.[10] In addition to their pectoral fins, skates have a first and second dorsal fin, caudal fin and paired pelvic fins. Distinct from their rhomboidal shape is a long fleshy slender tail. While skate anatomy is similar to other Batoidea, features such as their electric organ and mermaid's purse create clear distinctions.

Skate specific characteristics

[edit]Mermaid's purse

[edit]Skates produce their young in an egg case called a mermaid's purse. These egg cases have distinct characteristics that are individualized to each species.[13][7] This makes a great tool for identifying different species of skates. One of these identifiable structures is the keel. The keel is a flexible ridge that runs along the outside of the structure. Another characteristic is the number of embryos in the egg case. Some species contain only one embryo while others can have up to seven. The size of the fibrous shell around the case is another characteristic. Some species have thick layers on the exterior.

Electric organ

[edit]

The electric organ is a characteristic exclusive to aquatic species. Among the Chondrichthyes, the only groups to possess electric organs are the electric ray and the skates. Unlike many other electrogenic fishes, skates are unique in having paired electric organs which run longitudinally through the tail in the lateral musculature of the notochord.[14] The impulses put out by the electric organs of the skate are considered to be weak, asynchronous, long-lasting signals.[15] Although the anatomy of the skate's electric organ is well described, its function is poorly understood. Some research suggests the electric impulses are too weak to be a mechanism used for defense or hunting. It is also too irregular to be useful for electrolocation purposes.[15] The most reasonable explanation in the literature suggests that the electric organ discharges may be used as a form of communication used for reproduction purposes.[15]

Distribution and habitats

[edit]Skates are primarily found from the intertidal down to depths greater than 3,000 m (9,843 ft).[9] They are most commonly found along outer continental shelves and upper slopes.[16] They are typically more diverse at higher latitudes and in deep-water. In fact, skates are the only cartilaginous fish taxon to exhibit more diversity of species at higher latitudes. A cool, temperate to polar water in the deep sea can be a favorable environment for skates.[7] As the water becomes more shallow and warmer, skates are seen to be replaced by stingrays. Skates are absent from brackish and freshwater environments. However, there is a single estuarine species that has been found in Tasmania, Australia. Also, the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection has caught and studied skates within the Long Island Sound estuary.[17] Some skate fauna have been found inhabiting areas of rock cobble and high rocky relief.

Behavior and ecology

[edit]Reproduction

[edit]

Skates mate at the same nursery ground each year. In order to fertilize the egg, males use claspers, a structure attached to the pelvic fins. The claspers allow them to direct the flow of semen into the female's cloaca. Skates are oviparous, meaning they lay eggs with very little development in the mother. This is one major difference from rays, which are viviparous, meaning they give birth to live young. When a female skate is fertilized, a protected case forms around the embryo called an egg case, or more commonly mermaid's purse. This egg case is then deposited out of the mother's body onto the ocean floor where the skates develop for up to 15 months before they enter the external environment.

Diet and feeding

[edit]The majority of skates feed on bottom dwelling animals, such as shrimp, crab, oyster, clams, and other invertebrates. To feed on these animals they have grinding plates in their mouths. Skates are an influential part of the food webs of demersal marine communities. They utilize similar resources to those of other upper trophic-level marine predators, such as seabirds, marine mammals, and sharks. The flattened body shape, ventral eyes and well developed spiracles of the skate allows them to live benthically, buried in the sediment or using a longitudinal undulation of the pectoral fins known as Rajiform locomotion to glide along the water floor.[18] Current research suggests that some species of skates, in addition to their Rajiform locomotion, use their pelvic fins to perform ambulatory locomotion.[19] This form of locomotion performed by the skate is being explored as a possible origin for our own development of walking by looking for similar neural pathways used for movement between skates and animals walking on land.[20]

Skates versus stingrays

[edit]Skates are like stingrays in that they have five pairs of gill slits that are located ventrally, which means on the underside of their body (unlike sharks that have their gills located on their sides). Skates and rays both have pectoral fins that are flat and expanded, which are typically fused to the head. Both skates and stingrays typically have their eyes on top of their head. Skates also share similar feeding habits with rays.

Skates are different from rays in that they lack a whip-like tail and stinging spines. However, some skates have electric organs located in their tail. The main difference between skates and rays is that skates lay eggs, whereas rays give birth to live young.

Moreover, skates can be more abundant than rays, and are fished for food in some parts of the world.[21]

| Comparison of skates and stingrays | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Superficially, skates and stingrays appear somewhat similar.

However, there are fundamental differences.

| |||

| Characteristic | Skates | Rays | Sources |

| Reproduction | Skates are oviparous, that is they lay eggs. Their fertilized eggs are laid in a protective hard case called a mermaid's purse. | Rays are viviparous, that is, they bear their young inside their bodies and give birth to them alive. | [22] |

| Dorsal fin | Distinct | Missing or vestigial | [22] |

| Pelvic fins | Fins are divided into two lobes | Fins have one lobe | [23] |

| Tail | Fleshy tails which lack spines | Whip-like with one or two stinging spines | [22][23] |

| Protection | Rely on "thorny projections on their backs and tails for protection from predators" | Rely on stinging spines or barbs for protection (though some, such as manta rays lack these) | [22] |

| Teeth | Small | "Plate-like teeth adapted for crushing prey" | [22] |

| Size | Usually smaller than rays | Usually larger than skates | [22] |

| Colour | Often drab, brown or gray (but not always) | Often boldly patterned (but not always) | [23] |

| Habitat | Often deep water (but not always) | Often shallow water (but not always) | [23] |

Conservation

[edit]Skates have slow growth rates and, since they mature late, low reproductive rates. As a result, skates are vulnerable to overfishing and appear to have been overfished and are suffering reduced population levels in many parts of the world.

See also

[edit]- Jenny Haniver, a fake sea monster created from a skate carcass.

- Hongeohoe, a Korean dish made from fermented skate.

- Mokpo, a South Korean city famous for its skate cuisine.

References

[edit]- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Family Rajidae". FishBase. January 2009 version.

- ^ a b c Last, P.R.; Séret, B.; Stehmann, M.F.W.; Weigmann, S. (2016). "Skates: Family Rajidae". In Last, Peter; Naylor, Gavin; Séret, Bernard; White, William; de Carvalho, Marcelo; Stehmann, Matthias (eds.). Rays of the World. Csiro Publishing. pp. 204–363. ISBN 978-0-643-10914-8.

- ^ EBERT, D.A. (2003) The Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras of California. University California Press, Berkeley, CA. 284 pp.[page needed]

- ^ Compagno, Leonard J (1999). "Systematics and Body Form". In Hamlett, William C. (ed.). Sharks, Skates, and Rays: The Biology of Elasmobranch Fishes. JHU Press. pp. 1–42. ISBN 978-0-8018-6048-5.

- ^ UCMP Berkeley "Chondrichthyes: Fossil Record"

- ^ a b Marlétaz, Ferdinand; de la Calle-Mustienes, Elisa; Acemel, Rafael D.; Paliou, Christina; Naranjo, Silvia; Martínez-García, Pedro Manuel; Cases, Ildefonso; Sleight, Victoria A.; Hirschberger, Christine; Marcet-Houben, Marina; Navon, Dina; Andrescavage, Ali; Skvortsova, Ksenia; Duckett, Paul Edward; González-Rajal, Álvaro; Bogdanovic, Ozren; Gibcus, Johan H.; Yang, Liyan; Gallardo-Fuentes, Lourdes; Sospedra, Ismael; Lopez-Rios, Javier; Darbellay, Fabrice; Visel, Axel; Dekker, Job; Shubin, Neil; Gabaldón, Toni; Nakamura, Tetsuya; Tena, Juan J.; Lupiáñez, Darío G.; Rokhsar, Daniel S.; Gómez-Skarmeta, José Luis (20 April 2023). "The little skate genome and the evolutionary emergence of wing-like fins". Nature. 616 (7957): 495–503. Bibcode:2023Natur.616..495M. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05868-1. PMC 10115646. PMID 37046085.

- ^ a b c Ebert, David A.; Davis, Chante D. (18 January 2007). "Descriptions of skate egg cases (Chondrichthyes: Rajiformes: Rajoidei) from the eastern North Pacific". Zootaxa. 1393 (1). doi:10.11646/ZOOTAXA.1393.1.1.

- ^ a b Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Genera in the family Rajidae". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ a b Ebert, David A.; Compagno, Leonard J. V. (October 2007). "Biodiversity and systematics of skates (Chondrichthyes: Rajiformes: Rajoidei)". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 80 (2–3): 111–124. Bibcode:2007EnvBF..80..111E. doi:10.1007/s10641-007-9247-0. S2CID 22875855.

- ^ a b "Ray & Skate Anatomy :: Florida Museum of Natural History". www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu. 5 May 2017. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- ^ Berkovitz, Barry; Shellis, Peter (2017). The Teeth of Non-Mammalian Vertebrates. pp. 5–27. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-802850-6.00002-3. ISBN 9780128028506.

- ^ Carlos Bustamente; Julio Lamilla; Francisco Concha; David A. Ebert; Michael B. Bennett (29 June 2012). "Morphological Characters of the Thickbody Skate Amblyraja frerichsi (Krefft 1968) (Rajiformes: Rajidae), with Notes on Its Biology". PLOS One. 7 (8): e39963. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...739963B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039963. PMC 3386969. PMID 22768186.

- ^ Mabragaña, E.; Vazquez, D. M.; Gabbanelli, V.; Sabadin, D.; Barbini, S. A.; Lucifora, L. O. (September 2017). "Egg cases of the graytail skate Bathyraja griseocauda and the cuphead skate Bathyraja scaphiops from the south-west Atlantic Ocean". Journal of Fish Biology. 91 (3): 968–974. Bibcode:2017JFBio..91..968M. doi:10.1111/jfb.13380. hdl:11336/45691. PMID 28868748.

- ^ Macesic, Laura J.; Kajiura, Stephen M. (November 2009). "Electric organ morphology and function in the lesser electric ray, Narcine brasiliensis". Zoology. 112 (6): 442–450. Bibcode:2009Zool..112..442M. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2009.02.002. PMID 19651501.

- ^ a b c Koester, David M. (2003). "Anatomy and motor pathways of the electric organ of skates". The Anatomical Record. 273A (1): 648–662. doi:10.1002/ar.a.10076. PMID 12808649.

- ^ Ebert, David A.; Bizzarro, Joseph J. (October 2007). "Standardized diet compositions and trophic levels of skates (Chondrichthyes: Rajiformes: Rajoidei)". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 80 (2–3): 221–237. Bibcode:2007EnvBF..80..221E. doi:10.1007/s10641-007-9227-4. S2CID 1382600.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-28. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Hall, Brian K., ed. (2008). Fins into Limbs: Evolution, Development, and Transformation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31340-5. OCLC 308649613.[page needed]

- ^ Lucifora, Luis O.; Vassallo, Aldo I. (28 August 2002). "Walking in skates (Chondrichthyes, Rajidae): anatomy, behaviour and analogies to tetrapod locomotion". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 77 (1): 35–41. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8312.2002.00085.x. hdl:11336/128800.

- ^ Jung, Heekyung; Baek, Myungin; D’Elia, Kristen P.; Boisvert, Catherine; Currie, Peter D.; Tay, Boon-Hui; Venkatesh, Byrappa; Brown, Stuart M.; Heguy, Adriana; Schoppik, David; Dasen, Jeremy S. (February 2018). "The Ancient Origins of Neural Substrates for Land Walking". Cell. 172 (4): 667–682.e15. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.013. PMC 5808577. PMID 29425489.

- ^ Castro, Peter; Huber, Michael (2017). Marine Biology 10th Edition. Singapore: McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 155–158. ISBN 978-1-259-25199-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Ichthyology: Ray and Skate Basics Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d Skate or Ray? ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved 212 March 2013.

External links

[edit]Rajidae.

- ARKive – images and movies of the common skate (Dipturus batis)

- Kliman, Todd. "Skate Goes From Trash Fish to Treasure Archived 2012-03-19 at the Wayback Machine", Washingtonian, May 1, 2006.