Halton-with-Aughton

| Halton-with-Aughton | |

|---|---|

Halton village, viewed from the far river bank | |

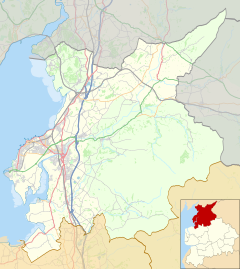

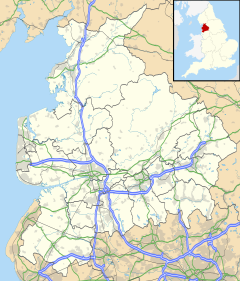

Location within Lancashire | |

| Population | 2,277 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SD502648 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LANCASTER |

| Postcode district | LA2 |

| Dialling code | 01524 |

| Police | Lancashire |

| Fire | Lancashire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Halton-with-Aughton is a civil parish and electoral ward located 3 miles (5 km) east of Lancaster, England, on the north bank of the River Lune. The main settlement is the village of Halton, or Halton-on-Lune, in the west, and the parish stretches to the hamlet of Aughton in the east. It lies in the City of Lancaster district of Lancashire, and has a population of 2,227,[1] down from 2,360 in 2001.[2]

Halton

[edit]Halton consists primarily of modern housing, amongst which can be found a number of 17th- and 18th-century buildings. It has a primary school and there is a post office and other local amenities including a very successful community centre. The village is on the edge of the new Heysham to M6 Link Road.[3]

Halton railway station was on the opposite bank of the river from the village, linked by a narrow toll bridge. The station closed in 1966, but the station building and part of one platform survive as the Lancaster University boat house, that sits beside the cycle path that was once the now disused "little" North Western Railway.

History

[edit]Halton was the centre of an important Anglo-Saxon manor held by Earl Tostig, the brother of King Harold before the Norman Conquest.[4] Count Roger of Poitou who held the fee after the regime change, and his successors, preferred Lancaster.[5]

The 19th-century textile mills once harnessed the power of the Lune. Earthworks on Castle Hill show evidence of an 11th-century Norman motte and bailey castle. In the churchyard of St Wilfrid's Church stands the Halton Cross believed to have been carved by Norsemen over 1,000 years ago.

Halton Castle was situated within the village of Halton. It is likely that a motte and bailey castle was constructed on the site in the late 11th century. However Halton's prominence was lost in the 12th century when favour shifted to Lancaster, and Halton Castle was abandoned. Only earthworks now remain and it is privately owned with no public right of way.

Halton Hall was part of the Manor of Halton and stood for several centuries on the banks of the River Lune before being demolished in the 1930s.

Industry

[edit]

In 1752 a charcoal blast furnace was erected on the Cote Beck, where the M6 motorway crosses Foundry Lane, and by 1755 the Halton Furnace Company ran it with those at Leighton and Caton Forge. The furnaces produced pig iron. The chamber was charged with charcoal,[a] limestone, and ore and a blast of air was blown into the base using water driven bellows. The molten iron (1530 C) ran down the furnace and was intermittently released in to the 'pig bed' of sand. It could produce 20 tons of pig iron a week- working for several weeks at a time. The 3-5% carbon pig iron was then decarburised in forges and purified in a finery forge to remove carbon and silicon in a process that used a trip hammer. In the chafery the metal was reheated and shaped with a trip hammer into an malleable iron bar. There were two forges on the river in Halton- the upper forge had six water-wheels, two fineries and two chaferies, the lower forge had a tilt and lift hammer. Coke furnaces had displaced most charcoal furnaces by 1800, though Halton hung on until 1845 servicing local need.[6] Nothing remains to be seen.

There was intensive industrial activity on the river bank in the 18th century with the forges and the construction of two water powered cotton mills: Forse Bank mill (1744) and Low Mill. Little to nothing now remain. Forse Bank mill whose name morphed into Forge Bank Mill was upstream. Water was taken from above the weir and two parallel leets powered all the buildings.[7] The mills have separate origins but eventually merged. Forse bank started spinning flax, in 1821 it was spinning cotton but in 1826 it was flax. Other buildings, including a forge were acquired and converted. After the Lancashire Cotton Famine in 1861, the spinning stopped - but in 1862 it was producing oilcloth, thus weaving. Eventually it was purchased by Williamson, who moved linoleum and oilcloth manufacture to Lancaster. Cotton weaving stopped in 1941.[7] Part of the site has been developed with eco-housing, which have proved to be very popular and sell quickly. Further development is currently underway.[8][9]

Railway

[edit]In 1849, the "little" North Western Railway built Halton station[10] on the other bank of the Lune, primarily to serve the forge. During construction it was linked to Halton village by a ferry. Eight people died when this capsized. In December 1849, the railway company built a toll bridge. It was washed away replaced in 1869 and replaced for the second time in 1913.[9] When the railway closed in 1966, the bridge fell into disrepair, it has been restored and is now free and open to small cars, pedestrians and cycles. [11] The original timber station was destroyed by fire on 3 April 1907. A spark from the engine of a passing Heysham–St Pancras boat train set fire to a wagon of oil drums by the goods shed. The fire brigade were unable to cross the narrow bridge and it was left to a special trainload of railway workers from Lancaster to pass buckets of water from the river.[12] The station was rebuilt in brick and timber and the building survives to this day, used as storage by Lancaster University Rowing Club, with a public car park occupying the former track bed.[13] The bridge is on National Cycle Network Route 90, and the trackbed on Route 69.

Aughton

[edit]

Aughton (/ˈæftən/) was known as 'Actun' in the 1086 Domesday Book, meaning a place where oak trees grow. A riverside hamlet by the River Lune, Aughton consists mainly of stone cottages and St Saviour's Church, which is located on Aughton Road to the north of the hamlet. The church was built in 1864 and designed by architect E. G. Paley.[14] Aughton lies within the Forest of Bowland Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Every 21 years the gigantic Aughton Pudding is baked over a celebratory weekend. The pudding made in 1992 was entered into the Guinness Book of Records as the largest, but the festival itself was run at a loss. The festival in 2013 was a great success. No world record was attempted but the attendance was over 5000 and the profit made divided between good causes, St Saviour's and the Recreation Rooms. This money was later loaned to Broadband 4 Rural North to bring 1 Gbps broadband to the village on 14 August 2014.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Halton-with-Aughton Parish (E04005189)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Parish headcount" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ Heysham to M6 Link, Lancashire County Council, accessed 16 October 2011

- ^ Clark (2010), p. 142

- ^ William Farrer and J Brownbill, ed. (1914). "A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 8: The parish of Halton". British History Online. London: Victoria County History. pp. 118–126. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ Price 1980, pp. 23–29.

- ^ a b Price 1980.

- ^ Brown, P. "We hear very different tales". Archive - Wednesday, 21 March 2007. The Westmorland Gazette. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ a b Self, John (2008). The Land of the Lune (PDF) (Second ed.). Lancaster: Drakkar Press. pp. 206–209. ISBN 978-0-9548605-2-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Butt, p.112

- ^ Suggitt 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Vinter 1990, pp. 137–8.

- ^ Suggitt 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Hartwell, Clare; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2009) [1969], Lancashire: North, The Buildings of England, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 88, ISBN 978-0-300-12667-9

- Bibliography

- Clark, Felicity H. (2010), "Wilfrid's Lands? The Lune Valley in its Anglican Context", in Server, Linda (ed.), Lancashire's Sacred Landscape, The History Press, ISBN 978-0-7524-5587-7

- Price, James (1980). "Forge Bank Mill, Halton" (A5). Contrebis. 8. LancasterArchaeological & History Society: 34–40. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- Butt, R. V. J. (October 1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199. OL 11956311M.

- Suggitt, Gordon (2004). Lost railways of Lancashire (2 ed.). Newbury: Countryside Books. ISBN 1-85306-801-2.

- Vinter, Jeff (1990). Railway walks. Gloucester: Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-735-6.