Jarrow

| Jarrow | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

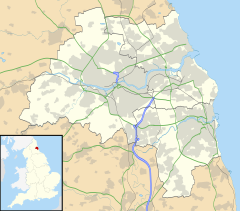

Location within Tyne and Wear | |

| Population | 27,526 |

| OS grid reference | NZ332651 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | JARROW |

| Postcode district | NE32 |

| Dialling code | 0191 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Tyne and Wear |

| Ambulance | North East |

| UK Parliament | |

Jarrow (/ˈdʒæroʊ/ or /ˈdʒærə/) is a town in South Tyneside in the county of Tyne and Wear, England. Historically in County Durham, it is on the south bank of the River Tyne, about 3 miles (4.8 km) from the east coast. The 2011 census area classed Hebburn and The Boldons as part of the town, it had a population of 43,431.[1] It is home to the southern portal of the Tyne Tunnel and 5 miles (8.0 km) east of Newcastle upon Tyne.

In the eighth century, St Paul's Monastery in Jarrow (now Monkwearmouth–Jarrow Abbey) was the home of The Venerable Bede, who is regarded as the greatest Anglo-Saxon scholar and the father of English history. The town is part of the historic County Palatine of Durham. From the middle of the 19th century until 1935, Jarrow was a centre for shipbuilding, and was the starting point of the Jarrow March against unemployment in 1936.

History

[edit]Toponymy

[edit]Jarrow's name is first recorded in the 8th century. It derives from the Gyrwe, an Anglian tribe that inhabited the neighbourhood. The Gyrwe's name means "fen dwellers", perhaps in reference to Jarrow Slake (a now-drained wetland that lay at the confluence of the Tyne and the Don). The place-name would normally have developed into Yarrow in modern English, but as with Jesmond, Norman influence resulted in the initial /j/ becoming /dʒ/.[2]

Monkwearmouth–Jarrow Abbey

[edit]

The Monastery of Paul of Tarsus in Jarrow, part of the twin foundation Monkwearmouth–Jarrow Abbey, was once the home of The Venerable Bede, whose most notable works include Ecclesiastical History of the English People and the translation of the Gospel of John into Old English. Along with the abbey at Wearmouth, Jarrow became a centre of learning and had the largest library north of the Alps, primarily due to the widespread travels of Benedict Biscop, its founder.[3] In 794 Jarrow became the second target in England of the Vikings, who had plundered Lindisfarne in 793. The monastery was later dissolved by Henry VIII. The ruins of the monastery are now associated with and partly built into the present-day church of St. Paul, which stands on the site. One wall of the church contains the oldest stained glass window in the world, dating from about AD 600. Just beside the monastery is Jarrow Hall, a working museum dedicated to the life and times of Bede. This incorporates Jarrow Hall, a grade II listed building and significant local landmark.

The world's oldest complete Bible, written in Latin to be presented to the then Pope (Gregory II), was produced at this monastery – the Codex Amiatinus. It is currently safeguarded in the Laurentian Library, Florence, Italy.[4]

Originally three copies of the Bible were commissioned by Ceolfrid in 692.[4] This date has been established as the double monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow secured a grant of additional land to raise the 2000 head of cattle needed to produce the vellum for the Bible's pages. Saint Ceolfrid accompanied one copy (originally intended for Gregory I) on its journey to be presented to Gregory II, but he died en route to Rome.[5] The book later appears in the ninth century in the Abbey of the Saviour, Monte Amiata in Tuscany (hence the description "Amiatinus"), where it remained until 1786 when it passed to the Laurentian Library in Florence.

19th century to present

[edit]

Jarrow remained a small mid-Tyne town until the introduction of heavy industries such as coal mining and shipbuilding. Charles Mark Palmer established a shipyard – Palmer's Shipbuilding and Iron Company – in 1852 and became the first armour-plate manufacturer in the world.[6] John Bowes, the first iron screw collier, revived the Tyne coal trade,[6] and Palmer's was also responsible for the first modern cargo ship,[6] as well as a number of notable warships.[6] Around 1,000 ships were built at the yard, they also produced small fishing boats to catch eel within the River Tyne, a delicacy at the time.[6] Jarrow Town Hall was erected in Grange Road and officially opened in 1904.[7]

Palmer's employed as much as 80% of the town's working population until its closure in 1933[8] following purchase by National Shipbuilders Securities Ltd. (NSS). This organisation had been set up by Stanley Baldwin's Conservative government in the 1920s, but the first public statement had been made in 1930 whilst the Labour Party was in office. The aim of NSS was to reduce capacity within the British shipyards. In fact Palmer's yard was relatively efficient and modern, but had serious financial problems.[9] As from 1935, Olympic, the sister ship of RMS Titanic, was partially demolished at Jarrow,[10] being towed in 1937 to Inverkeithing, Scotland for final scrapping.[11]

The Great Depression brought so much hardship to Jarrow that the town was described by Life as "cursed."[12] The closure of the shipyard was responsible for one of the events for which Jarrow is best known. Jarrow is marked in history as the starting point in 1936 of the Jarrow March to London to protest against unemployment in Britain. Jarrow Member of Parliament (MP) Ellen Wilkinson wrote about these events in her book The Town That Was Murdered (1939). Some doubt has been cast by historians as to how effective events such as the Jarrow March actually were[13] but there is some evidence that they stimulated interest in regenerating 'distressed areas'.[14] 1938 saw the establishment of a ship breaking yard and engineering works in the town, followed by the creation of a steelworks in 1939.[15]

The Jarrow rail disaster was a train collision that occurred on the 17 December 1915 at the Bede junction on a North Eastern Railway line.[16] The collision was caused by a signalman's error and seventeen people died in the collision.[16]

The Second World War revived the town's fortunes as the Royal Navy was in need of ships to be built. After 1945 the shipbuilding industries were nationalised. The last shipyard in the town closed in 1980.[8]

In August 2014 a group of mothers from Darlington organised a march from Jarrow to London to oppose the privatisation of the NHS. The march took place in September 2014 and 3,000–5,000 people participated in the event.[17]

Education

[edit]Jarrow's needs for secondary education are currently served by Jarrow School, formerly Springfield Comprehensive.[18] Springfield was merged with another of Jarrow's secondary schools, Hedworthfield Comprehensive at Fellgate, following a gradual reduction of the number of new pupils for the yearly intake of 11-year-olds to the point where keeping both schools open was no longer viable. As of 2008 plans to revamp Jarrow School have come into action. Building work was completed in 2009 turning the school into a modern learning facility with Specialist Engineering Status. The head teacher at the school plans to improve the school's grade point average, by improving the learning facilities, costing millions of pounds.

Demography

[edit]In 2011, Jarrow had a population of 43,431, compared to 27,526 in 2001. This gives Jarrow a similar population to Wallsend and Whitley Bay.[1] The large increase in population is mainly due to boundary changes.

| Jarrow compared 2011 census | Jarrow | South Tyneside |

|---|---|---|

| White British | 97.1% | 95.0% |

| Asian | 1.1% | 2.2% |

| Black | 0.2% | 0.3% |

The fact that only 2.9% of Jarrow's population is non White British, makes Jarrow the least ethnically diverse major urban subdivision in Tyneside and less ethnically diverse than its surrounding borough, South Tyneside. Jarrow contains areas such as Fellgate and Hedworth, which border onto Greenbelt in the south of the town, which have very high White British populations. In South Tyneside, 5.0% of the population are non-White British, which is almost double the figure for Jarrow, also the borough has twice the percentage of Asian people compared to this riverside town.

Compared to the rest of the North East of England Jarrow does have an increased rate of unemployment, average unemployment figures in 2013 put the north east at 5.4% as opposed to Jarrow at 6.1%.[19] In September 2016 1,680 people living in Jarrow were in receipt of Job Seekers Allowance or Universal Credit, 370 people aged between 18 and 24 were on receipt of benefits in September 2016 down by 30 from last year, a drop of 7.5%.[20]

Notable people

[edit]- Roger Avon, actor[21]

- Bede, Benedictine monk and scholar

- Catherine Cookson, writer[22]

- Steve Cram, Olympic athlete (the "Jarrow Arrow")

- Ray Drinkwater, goalkeeper with Queens Park Rangers

- Christie Elliot, professional footballer with Dundee.

- Peter Flannery, playwright[23]

- William Goat, winner of the Victoria Cross for attempting to retrieve the body of a major whilst under attack by hostile cavalry, returning later under heavy fire to complete the task.[24]

- Stephen Hepburn, politician

- James Johnston, socialist activist[25]

- Ray Lugg, professional footballer, born in Jarrow in 1948

- Jem Mace, famous pugilist died at 6 Princess Street, Jarrow in 1910[26]

- Aidan McCaffery, former Newcastle United footballer.

- John Miles, rock musician, singer, songwriter[27]

- Fergus Montgomery, Conservative MP[28]

- Charles Mark Palmer, shipbuilder, first mayor of Jarrow

- Alan Plater, writer[29]

- Alan Price, musician, born in Washington and brought up in Jarrow[30]

- Steve Robson, songwriter and record producer

- David Sharpe, silver medalist at 1992 European Championships over 800 metres

- Gareth Smith, cricketer

- Sir Patrick Stewart, actor, spent the majority of his childhood living in Jarrow, although was born in Mirfield, West Riding of Yorkshire.[31]

- Paul Thompson, rock musician, drummer of Roxy Music[32]

- Jimmy Thorpe, Sunderland goalkeeper who died helping the club win the 1936 League title

- Frank Williams, Formula One team manager, was brought up in Jarrow[33]

- Ellen Wilkinson, Labour MP and Jarrow March organiser.

- Wee Georgie Wood, music hall star.[34]

- Dan Neil, Sunderland midfielder.

In popular culture

[edit]- In 1970, Jarrow was the setting of the first in a series of "Spanish Inquisition" sketches in Monty Python's Flying Circus, one of the best-known and quoted sketches by the comedy troupe. An establishing shot of the town shows two nuclear power plant cooling towers in the background and is overlaid with a graphics reading "Jarrow - New Year's Eve 1911" and then "Jarrow - 1912". Another sketch refers to a Jarrow United football team.[35]

Twin towns

[edit]Jarrow is twinned with the following towns, under the umbrella of the South Tyneside town-twinning project which saw individual twinning projects brought together in 1974:

- Wuppertal in Germany,[36] originally twinned with South Shields in 1951.

- Noisy-le-Sec in France,[37] originally twinned with Hebburn in April 1963.

- Épinay-sur-Seine in France,[37] originally twinned with Jarrow in June 1965.

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – (E35001236)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Watts, Victor, ed. (2010). The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names. Cambridge University Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-521-16855-7.

- ^ Benedetto, Robert; Duke, James O. (2008). The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The early, medieval, and Reformation eras. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 673. ISBN 978-0-664-22416-5. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Codex Amiatinus Bible returns to its home in Jarrow". BBC News. 15 May 2014. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament (Oxford University Press 2005), p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e Chronicle staff (28 February 2013). "Collier who steamed into North legend". chroniclelive.co.uk. Newcastle: Chronicle. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Historic England. "Jarrow Town Hall (1299416)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ a b "On This Day: Jarrow Crusade unemployment march begins". uk.news.yahoo.com. 4 October 2013. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Roberts, Martin (2001). Britain, 1846–1964: The Challenge of Change. Oxford: Oxford UP. p. 218. ISBN 978-0199133734. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ "Titanic sister ship's Jarrow links". www.shieldsgazette.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "RMS Olympic – White Star Line History Website (White Star History)". www.whitestarhistory.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Life Magazine 14 December 1936, page 41

- ^ Lloyd, T.O. Empire to Welfare State, 1970

- ^ Marwick, Arthur. Britain in our Century 1984

- ^ "BBC – History – British History in depth: The Jarrow Crusade". Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ a b Henderson, Tony (18 December 2015). "Jarrow rail disaster victims are give memorial on 100th anniversary of tragedy". chroniclelive.co.uk. Newcastle: Chronicle. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "'Jarrow March' ends in pro-NHS rally in London". BBC News. 6 September 2014. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Gazette Staff (5 June 2010). "Jarrow landmark bites the dust". Shields Gazette. shieldsgazette.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ Rogers, Simon; Evans, Lisa (17 November 2010). "Unemployment: the key UK data and benefit claimants for every constituency". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ McGuinness, Feargal; Davies, James Mirza; Oneill, Marianne (20 October 2021). "Unemployment by Constituency, October 2016".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Roger Avon obituary – The Doctor Who Cuttings Archive". cuttingsarchive.org. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "Obituary: Dame Catherine Cookson". The Independent. 11 June 1998. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "An Interview with Peter Flannery". The Oxonian Review. 16 December 2012. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Kingdom, Customer Contact Centre, Town Hall & Civic Offices,, Westoe Road, South Shields, Tyne & Wear, NE33 2RL, United. "New Honour For Victoria Cross Holders". www.southtyneside.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Margaret 'Esipinasse and Judith Fincher Laird, Dictionary of Labour Biography (vol.5), pp.121–124

- ^ "Swansong for Jem of a boxer". The Northern Echo. 24 August 2004. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ "John Miles". www.john-miles.net. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Telegraph Staff (19 March 2013). "Sir Fergus Montgomery". The Telegraph. London: telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ "BFI Screenonline: Plater, Alan (1935–2010) Biography". www.screenonline.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "Singer songwriter Alan Price talks of his North East roots". North East Life. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Barratt, Nick (12 January 2007). "Family detective". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Morton, David (10 December 2015). "From Roxy Music to Lindisfarne with ace North East drummer Paul Thompson". Chronicle. Newcastle: chroniclelive.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ "South Shields Formula One legend Sir Frank Williams is admitted to hospital". 16 December 2020. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Knewstub, Nikki (13 August 2008). "Georgie Wood's wee way to success". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "10 reasons why Monty Python still makes us laugh". Channel 4. July 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ "Twin Town Mayor Pays a Visit to South Tyneside - South Tyneside Council". Archived from the original on 2 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Brexit will not break South Tyneside's long-standing friendship with German twin city Wuppertal". 26 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Gibbs, Philip. England speaks (1935)

- Lloyd, T.O. Empire to Welfare State (1970)

- Marwick, Arthur. Britain in our Century (1984)

- Wilkinson, Ellen. The Town That Was Murdered: Depicting in Brief the History and Demise of Jarrow (1939)

External links

[edit]- South Tyneside Council & Community website – Local council website

- BBC History: The Jarrow Crusade