Generalplan Ost

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (April 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

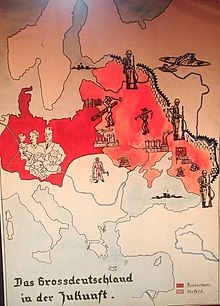

| Master Plan for the East | |

Plan of new German settlement colonies (marked with dots and diamonds), drawn up by the Friedrich Wilhelm University Institute of Agriculture in Berlin, 1942, covering the Baltic states, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and Russia | |

| Duration | 1941–1945 |

|---|---|

| Location | Territories controlled by Nazi Germany |

| Type | Genocide, ethnic cleansing, slave labour and kidnapping of children |

| Cause | Nazi racism, Nazi racial policy, Nazi bio-geo-political Weltanschauung,[1] Manifest destiny,[2][3] Lebensraum and Heim ins Reich |

| Patron(s) | Adolf Hitler |

| Objectives |

|

| Deaths | |

| Outcome | Nazi abandonment of GPO due to Axis defeat in the Eastern Front |

The Generalplan Ost (German pronunciation: [ɡenəˈʁaːlˌplaːn ˈɔst]; English: Master Plan for the East), abbreviated GPO, was Nazi Germany's plan for the genocide, extermination and large-scale ethnic cleansing of Slavs, Eastern European Jews, and other indigenous peoples of Eastern Europe categorized as "Untermenschen" in Nazi ideology.[7][5] The campaign was a precursor to Nazi Germany's planned colonisation of Central and Eastern Europe by Germanic settlers, and it was carried out through systematic massacres, mass starvations, chattel labour, mass rapes, child abductions, and sexual slavery.[8][9]

Generalplan Ost was only partially implemented during the war in territories occupied by Germany on the Eastern Front during World War II, resulting indirectly and directly in the deaths of millions by shootings, starvation, disease, extermination through labour, and genocide. However, its full implementation was not considered practicable during major military operations, and never materialised due to Germany's defeat.[10][11][12] Under direct orders from Nazi leadership, around 11 million Slavs were killed in systematic violence and state terrorism carried out as part of the GPO. In addition to genocide, millions more were forced into slave labour to serve the German war economy.[5]

The program's operational guidelines were based on the policy of Lebensraum proposed by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in fulfilment of the Drang nach Osten (drive to the East) ideology of German expansionism. As such, it was intended to be a part of the New Order in Europe.[13] Approximately 3.3 million Soviet POWs captured by the Wehrmacht were killed as part of the GPO. The plan intended for the genocide of the majority of Slavic inhabitants by various means – mass killings, forced starvations, slave labour and other occupation policies. The remaining populations were to be forcibly deported beyond the Urals, paving the way for German settlers.[14]

The plan was a work in progress. There are four known versions of it, developed as time went on. After the invasion of Poland, the original blueprint for Generalplan Ost was discussed by the RKFDV in mid-1940 during the Nazi–Soviet population transfers. The second known version of the GPO was procured by the RSHA from Erhard Wetzel in April 1942. The third version was officially dated June 1942. The final version of the Master Plan for the East came from the RKFDV on October 29, 1942. However, after the German defeat at Stalingrad, resources allocated to colonization policies were diverted to Axis war efforts, and the program was gradually abandoned.[15]

Background

Ideological motivations

Generalplan Ost was Nazi Germany's plan for the colonization and Germanization of Central and Eastern Europe over a period of twenty-five years.[16][17][18] Implementing it would have necessitated genocide[19] and ethnic cleansing on a vast scale to be undertaken in the Eastern European territories occupied by Germany during World War II. It would have included the extermination and de-population of most Slavic people in Eastern Europe.[20]

The plan, prepared in the years 1939–1942, was part of Adolf Hitler's and the Nazi movement's Lebensraum policy and a fulfilment of the Drang nach Osten (English: Drive towards the East) ideology of German expansion to the east, both of them part of the larger plan to establish the New Order. More than economic calculations, ideological fanaticism and racism played a central role in Nazi regime's implementation of extermination programs such as the GPO.[21] Hitler's doctrine of Lebensraum envisaged the mass-killings, enslavement and ethnic cleansing of Slavic inhabitants of Eastern Europe, followed by the colonization of these lands with Germanic settlers.[22]

Although racist views against Slavs had precedent in German society before Hitler's rule, Nazi anti-Slavism was also based on the doctrines of scientific racism. The "Master Race" doctrine of Nazi ideology condemned Slavs to permanent domination by Germanic peoples, since it viewed them as primitive people who lacked the ability to undertake autonomous activities.[23] Generalplan Ost evolved from these racist, imperialist ideas and was formulated by the Nazi regime as its official policy during the course of the Second World War.[22]

"... when we speak of new territory in Europe today we must principally think of Russia and the border states subject to her. Destiny itself seems to wish to point out the way for us here. In delivering Russia over to Bolshevism, fate robbed the Russian people of that intellectual class which had once created the Russian state and were the guarantee of its existence. For the Russian state was not organized by the constructive political talent of the Slav element in Russia, but was much more a marvellous exemplification of the capacity for state-building possessed by the Germanic element in a race of inferior worth. ... This colossal empire in the East is ripe for dissolution. And the end of the Jewish domination in Russia will also be the end of Russia as a state. We are chosen by destiny to be the witnesses of a catastrophe which will afford the strongest confirmation of the nationalist theory of race."

Himmler's role

The body responsible for the Generalplan Ost was the SS's Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) under Heinrich Himmler, which commissioned the work. The document was revised several times between June 1941 and spring 1942 as the war in the east progressed successfully. It was a confidential proposal whose content was known only to those at the top level of the Nazi hierarchy; it was circulated by RSHA to the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (Ostministerium) in early 1942.[25]

Between 1940 and 1943, Himmler supervised the drafting of at least five variants of Generalplan Ost. Four of these drafts were produced by the office of Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood (RKFDV) and one draft was produced by the RSHA. SS Race and Settlement Main Office and Ostministerium were also involved in the formulating the GPO plans.[26] According to testimony of SS-Standartenführer Hans Ehlich (one of the witnesses before the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials), the original version of the plan was drafted in 1940. As a high official in the RSHA, Ehlich was the man responsible for the drafting of Generalplan Ost along with Konrad Meyer, Chief of the Planning Office of Himmler's RFKDV. It had been preceded by the Ostforschung.[25]

The preliminary versions were discussed by Heinrich Himmler and his most trusted colleagues even before the outbreak of war. This was mentioned by SS-Obergruppenführer Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski during his evidence as a prosecution witness in the trial of officials of the SS Race and Settlement Main Office (RuSHA). According to Bach-Zelewski, Himmler stated openly: "It is a question of existence, thus it will be a racial struggle of pitiless severity, in the course of which 20 to 30 million Slavs and Jews will perish through military actions and crises of food supply."[25] A fundamental change in the plan was introduced on June 24, 1941 – two days after the start of Operation Barbarossa – when the 'solution' to the Jewish question ceased to be part of that particular framework gaining a lethal, autonomous priority.[25]

Cost

The planning had included implementation cost estimates, which ranged from 40 to 67 billion Reichsmarks, the latter figure being close to Germany's entire GDP for 1941.[27] A cost estimate of 45.7 billion Reichsmarks was included in the spring 1942 version of the plan, in which more than half the expenditure was to be allocated to land remediation, agricultural development, and transport infrastructure. This aspect of the funding was to be provided directly from state sources and the remainder, for urban and industrial development projects, was to be raised on commercial terms.[28]

Scale of planned casualties

The main objective of Generalplan Ost was to establish a pure "German and Aryan" community in Eastern Europe, composed of individuals who would be loyal subjects of the Greater Germanic Reich. Full implementation of the Generalplan Ost aimed at the forced deportations of hundreds of millions of Eastern European natives beyond the Urals and in the slaughter of more than 60 million Slavs, Romanis and Jews.[29] The extermination programme also involved the policy known as the "Hunger Plan", which would have killed more than 30 million Slavic natives in forced starvations.[30][8][31]

GPO also envisaged the forced expulsion of around 80 million Russians beyond the Urals, with Nazi planners estimating the deaths of approximately 30 million Russians in the ensuing death marches.[32]

Phases of the plan and its implementation

| Ethnic group / Nationality targeted |

Percentage of ethnic group to be removed by Nazi Germany from future settlement areas[19][33][34] |

|---|---|

| Russians[35][36] | 70–80 million |

| Estonians[34][37] | almost 50% |

| Latvians[34] | 50% |

| Czechs[33] | 50% |

| Ukrainians[33][38] | 65% to be deported from Western Ukraine, 35% to be Germanized |

| Belarusians[33] | 75% |

| Poles[33] | 20 million, or 80–85% |

| Lithuanians[34] | 85% |

| Latgalians[34] | 100% |

LEGEND:

Dark grey – Germany (Deutsches Reich).

Dotted black line – the extension of a detailed plan of the "second phase of settlement" (zweite Siedlungsphase).

Light grey – planned territorial scope of the Reichskommissariat administrative units; their names in blue are Ostland (1941–1945), Ukraine (1941–1944), Moskowien (not realized), and Kaukasien (not realized).

Widely varying policies were envisioned by the creators of Generalplan Ost, and some of them were actually implemented by Germany in regards to the different Slavic territories and ethnic groups. For example, by August–September 1939 (Operation Tannenberg followed by the A-B Aktion in 1940), Einsatzgruppen death squads and concentration camps had been employed to deal with the Polish elite, while the small number of Czech intelligentsia were allowed to emigrate overseas. Parts of Poland were annexed by Germany early in the war (leaving aside the rump German-controlled General Government and the areas previously annexed by the Soviet Union), while the other territories were officially occupied by or allied to Germany (for example, the Slovak part of Czechoslovakia became a theoretically independent puppet state, while the ethnic-Czech parts of the Czech lands (so excluding the Sudetenland) became a "protectorate"). The plan was partially attempted during the war, resulting indirectly and directly in millions of deaths of ethnic Slavs by starvation, disease, or extermination through labor.[12] The majority of Germany's 12 million forced laborers were abducted from Eastern Europe, mostly in the Soviet territories and Poland.[39]

The final version of the Generalplan Ost proposal was divided into two parts; the "Small Plan" (Kleine Planung), which covered actions carried out in the course of the war; and the "Big Plan" (Grosse Planung), which described steps to be taken gradually over a period of 25 to 30 years after the war was won. Both plans entailed the policy of ethnic cleansing.[40][41] As of June 1941, the policy envisaged the deportation of 31 million Slavs to Siberia.[25] 75% of Belorussians were regarded unfit for "Germanization" and targeted for extermination or expulsion.[21]

"The treatment of the civilian population and the methods of anti-partisan warfare in operational areas presented the highest political and military leaders with a welcome opportunity to carry out their plans, namely, the systematic extermination of Slavism and Jewry."

The Generalplan Ost proposal offered various percentages of the conquered or colonized people who were targeted for removal and physical destruction; the net effect of which would be to ensure that the conquered territories would become German. In ten years' time, the plan effectively called for the extermination, expulsion, Germanization or enslavement of most or all East and West Slavs living behind the front lines of East-Central Europe. The "Small Plan" was to be put into practice as the Germans conquered the areas to the east of their pre-war borders.[citation needed] After the war, under the "Big Plan", more people in Eastern Europe were to be affected.[34][33][43][40]

In their place, settlements of up to 10 million Germans were planned to be established in an extended "living space" (Lebensraum), as part of the GPO plan. GPO envisaged the establishment of settlements and "village complexes", each capable of hosting around 300-400 Germanic settlers. Because the number of Germans appeared to be insufficient to populate the vast territories of Central and Eastern Europe, the peoples which the Nazi theorists regarded as being capable of Germanisation and as racially intermediate between the Germans and the Russians (Mittelschicht), namely, Latvians and even Czechs, were also considered to be resettled there.[44][45] Several Nazi scientists, many of whom were members of the SS, were involved in the planning of GPO. The programme delineated various settler-colonial policies to be undertaken by Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe over a period of 25 years; such as the establishment of new settlements, demographic engineering, construction of new centres, etc., after the planned liquidation of the native populations.[46]

As early as the initial phase of Operation Barbarossa, when Wehrmacht was advancing deep inside Soviet territories while facing little or no local insurrections, Adolf Hitler had contemplated the utility of anti-insurgency campaigns in advancing his Lebensraum program:

a partisans’ war also has its advantage; it enables us to eradicate what is against us.

— Adolf Hitler, "Aktenvermerk vom 16. Juli 1941 über eine Besprechung Hitlers mit Rosenberg, Lammers, Keitel und Göring", [47]

While various Wehrmacht commanders wanted to portray Germans as "liberators" of Eastern Europe and incite anti-communist dissidents to foment a pro-Axis partisan warfare against Soviet Union, Nazi ruling elites sought outright suppression of what they regarded as Slavic "untermenschen". Hardliners like Himmler were averse to initiating agreements with Slavic natives. Hitler was strongly opposed to the entry of Slavic volunteers into the German army and issued orders to disarm the natives.[48][49] The initial assessment of Hitler and Wehrmacht generals was that Operation Barbarossa could be completed within months without any outside support. During a speech in 16 July 1941, Hitler proclaimed:

"No one but the Germans should ever be allowed to bear arms ... Only a German should bear arms: not a Slav, a Czech, a Cossack or a Ukrainian."[50]

German implementation of Nazi racial principles, combined with the severity of the war in the Eastern Front, resulted in German-occupation forces inflicting brutal measures during its anti-insurgency campaigns. The Schutzstaffel military apparatus, packed with militants ideologically indoctrinated to view Slavs as subhumans, fanatically implemented "Herrenvolk vs. Untermensch" racist criteria in their dealings with natives. Military leadership issued orders to inflict collective punishment against native inhabitants. However, as Axis advances gave way to a war of attrition and as German losses mounted, some Wehrmacht officers began proposing collaborationist policies with the natives, with the purpose of advancing German economic and geo-strategic interests.[52] Even as deteriorating conditions in the front brought around a change in military strategy,[50] speeches of various Wehrmacht generals continued to explicitly and implicitly designate German fighters as "the last bulwark of European civilisation against Slav hordes".[53]

Exploiting anti-semitic sentiments which had persisted since the Tsarist period in occupied territories, collaborationism was also incited amongst the native inhabitants to assist Nazi Germany in implementing the Holocaust. The collaborationist bodies were viewed with suspicion due to the hardline anti-Slavic policy of German occupiers, and their Nazi sponsors largely used these groups as cannon fodder for German war efforts. As a consequence of the ideological constraints of National Socialism and Wehrmacht's rising casualties across the Eastern Front, German units faced shortages of personnel in carrying out the "Final Solution".[54] As anti-fascist partisan warfare intensified across the German-occupied territories of Eastern Europe, Poland, and Yugoslavia, Hitler stated on 6 August 1942: “We shall absorb or eject a ridiculous hundred million Slavs. Whoever talks about caring for them should at once be put into a concentration camp”.[55]

According to Nazi intentions, attempts at Germanization were to be undertaken only in the case of those foreign nationals in Central and Eastern Europe who could be considered a desirable element for the future Reich from the point of view of its racial theories. The plan stipulated that there were to be different methods of treating particular nations and even particular groups within them. Attempts were even made to establish the basic criteria to be used in determining whether a given group lent itself to Germanization. These criteria were to be applied more liberally in the case of nations whose racial material (rassische Substanz) and level of cultural development made them more suitable than others for Germanization. The plan considered that there were a large number of such elements among the Baltic states. Erhard Wetzel felt that thought should be given to a possible Germanization of the whole of the Estonian nation and a sizable proportion of the Latvians. On the other hand, the Lithuanians seemed less desirable since "they contained too great an admixture of Slav blood." Himmler's view was that "almost the whole of the Lithuanian nation would have to be deported to the East".[33] Himmler is described as having had a positive attitude towards Germanising the populations of border areas of Slovenia (Upper Carniola and Southern Styria) and Bohemia-Moravia, but not Lithuania, claiming its population to be of "inferior race".[57]

Himmler's notorious policies included the weaponization of schooling system in occupied territories to Germanize kids and indoctrinate them with Nazi doctrines. Special institutes for children in occupied territories were operated to separate kids who were categorised by Nazi authorities as "racially suitable" from the local inhabitants, wherein they were indoctrinated to be transferred to families in Germany.[58] Despite the obstruction of German war efforts by the colonization policies and scorched earth tactics unleashed against native populations, Himmler dogmatically pursued the implementation of GPO programme and proposed the further expansion of Konrad Meyer's plan.[59] GPO policies hindered the German military from efficiently exploiting the resources from occupied territories during 1942, a decisive phase of the war during which Axis forces had the capability to potentially win in the Eastern Front, before the Red Army could amass more strength.[60]

After the German defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad and other Axis setbacks in the Eastern Front, Nazi planners were forced to practically abandon the extermination campaigns of the GPO by mid-1943.[61][62] From spring 1943, SS adopted the "Vernichtung durch Arbeit" (trans: "Extermination through labour") policy, which focused on exploiting natives in occupied territories as forced labor to aid German economy and military industry. By late 1943, millions of captives were employed in slave labour camps across German-occupied territories.[63]

GPO implementation by region

Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany launched forced starvations and advanced a "war of annihilation" (Vernichtungskrieg) in the Eastern Front to implement the Generalplan Ost. The Wehrmacht implemented scorched-earth tactics throughout the region and forcibly expelled natives en masse to the east. Nazi officials then charted out buffer zones intended to serve as future Nordic settlements. Hunger Plan was Nazi Germany's strategy to forcibly starve around 31 to 45 million Eastern Europeans by capturing food stocks and redirecting them to German forces.[64][8]

Nazi Germany conducted its warfare in the Eastern Front as a colonialist campaign of plunder and slaughter, involving the unhinged looting of resources and wholesale terrorism against native populations. German occupation policies in Eastern Europe were characterized by genocide through "war of annihilation", and were ideologically driven by the Nazi racist doctrines and settler-colonial policy of Lebensraum.[65]

Baltic region

Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were to be deprived of their statehood, while their territories were to be included in the area of German settlement. This meant that Latvia and especially Lithuania would be covered by the deportation plans, though in a somewhat milder form than the expulsion of Slavs to western Siberia. While the Estonians would be spared repressions and physical liquidation (that the Jews and the Poles were experiencing), in the long term the Nazi planners did not foresee their existence as independent entities and they would ultimately be deported as well, with eventual denationalisation; initial designs were for Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia to be Germanised within 25 years; Heinrich Himmler revised them to 20 years.[66]

Despite German opposition to their attempts of state-formation, Baltic natives were classified as "superior" to Slavs in the Nazi racial hierarchy. Therefore, German authorities implemented a deeper scale of collaborationist policy in the Baltic society. Nazi collaborationists amongst the Latvian, Lithuanian and Estonian natives were given senior posts in the administrative bodies of the German occupation. In German-occupied Lithuania, a civilian administration which controlled its internal security was tolerated. This semi-autonomous entity existed within the Reichskommissariat Ostland. Such concessions were non-existent in Poland, Ukraine and Belarussia, where the Germanic occupation policy was characterised by full-blown colonization, exploitation of resources, state-terrorism and forcing natives into slave labour.[67]

Belarussia

RSHA's GPO program had categorised 75% of Belarussians as "Eindeutschungsunfähig" (trans: "ineligible for Germanization"); targeting them for ethnic cleansing or violent eradication. After forcibly expelling or exterminating an estimated 5-6 millions of its native inhabitants, these lands were then supposed to be handed over to Germanic settlers for implementing the Lebensraum agenda.[58] Child indoctrination institutions which hosted numerous Belarussian children forcibly were also opened, wherein kids categorised as "racially suitable" were prepared to be transferred to Germany. The first of these centres in Belarus was set up in Bobruysk.[58]

Nazi anti-insurgency warfare conducted across occupied Eastern Europe was also used as an opportunity by German authorities to advance the objectives of GPO and Lebensraum settler-colonial agenda. In Belarussia, divisions of Wehrmacht and SS committed numerous massacres and unleashed state-terror indiscriminately against the native populations, in operations labelled "anti-partisan undertakings".[68]

Poland

In 1941, the German leadership decided to destroy the Polish nation completely, and in 15–20 years the Polish state under German occupation was to be fully cleared of any ethnic Poles and settled by German colonists.[70]: 32 A majority of them, now deprived of their leaders and most of their intelligentsia (through mass murder, destruction of culture, banning education above the absolutely basic level, and kidnapping of children for Germanization), would have to be deported to regions in the East and scattered over as wide an area of Western Siberia as possible. According to the plan, this would result in their assimilation by the local populations, which would cause the Poles to vanish as a nation.[44]

Approximately two million ethnic Poles were subjected to a forced Germanization campaign as part of the GPO. According to the plan, by 1952 only about 3–4 million 'non-Germanized' Poles (all of them peasants) were to be left residing in the former Poland. Those of them who would still not Germanize were to be forbidden to marry, the existing ban on any medical help to Poles in Germany would be extended, and eventually Poles would cease to exist. Experiments in mass sterilization in concentration camps may also have been intended for use on the populations.[71] The Wehrbauer, or soldier-peasants, would be settled in a fortified line to prevent civilization reanimating beyond the Ural Mountains and threatening Germany.[72] "Tough peasant races" would serve as a bulwark against attack[73] – however, it was not very far east of the "frontier" that the westernmost reaches within continental Asia of the Nazi Germany's major Axis partner, Imperial Japan's own Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere would have existed, had a complete defeat of the Soviet Union occurred.

Russia

Hitler envisioned the war in Eastern Europe as a campaign of annihilation, intending to culminate it with the decimation of the Russian state, its cities, and symbols of Russian culture in the event of a Nazi victory.[74][75] On 21 July 1940, Hitler ordered German army commander-in-chief Walther von Brauchitsch to prepare a war-plan to eliminate what he described as the "Russian problem". In a meeting before Wehrmacht military commanders on 31 July 1940, Hitler announced his "final decision" to "finish off" Russia through the initiation of a large military invasion in the spring of 1941.[76]

During Operation Barbarossa, German soldiers ruthlessly perpetrated mass-slaughter of Russian captives as part of the GPO.[77][78][79] Out of the 3.2 million Soviet prisoners captured by German forces by December 1941, approximately 2 million had been killed by February 1942, mostly through forced starvation, death marches and mass shootings.[80][81]

As part of the implementation of the Generalplan Ost, the Nazi regime intended to organize the rounding up of approximately 80 million Russians and expel them beyond the Urals. Nazi bureaucrats estimated that nearly 30 million Russians would have died during the planned death marches to regions beyond the Urals, such as Siberia.[32]

Ukraine

Between 1941 and 1945, approximately three million Ukrainians and other non-Jews were mass-murdered as part of Nazi extermination policies implemented across the regions of Ukraine.[82][83] In addition, between 850,000[84][85][86]–1,600,000 Jews were killed by Nazi forces in Ukraine during this period, with the assistance of local collaborators.[87][88]

Original Nazi plans advocated the extermination of 65 percent of 23.2 million Ukrainians,[89][90] with the survivors treated as chattel slaves.[91] Over 2,300,000 Ukrainians were deported to Germany and forced into Nazi slave labor.[92]

Nazi seizure of food supplies in Ukraine just like Soviets did in 1932-33 brought about starvation, as it was intended to do to depopulate that region for German settlement.[93] Soldiers were told to steel their hearts against starving women and children, because every bit of food given to them was stolen from the German people, endangering their nourishment.[94]

Yugoslavia

After conquering Yugoslavia in April 1941, Nazi Germany partitioned the country and installed puppet dictatorships in Serbia and Croatia. Many of the Yugoslavian territories were annexed by Germany, Italy, Hungary and Bulgaria.[95] Despite the vast population of Slavs in Yugoslavia, Nazi Germany mainly focused on targeting the nation's Jewish and Roma population.[95]

Destruction of documents, post-war reconstruction

Nearly all the wartime documentation on Generalplan Ost was deliberately destroyed shortly before Germany's defeat in May 1945,[43][96] and the full proposal has never been found, though several documents refer to it or supplement it. Nonetheless, most of the plan's essential elements have been reconstructed from related memos, abstracts and other documents.[40] Following the war, two out of the three primary records associated with the Generalplan Ost were lost. These included the document drafted by Konrad Meyer; in addition to an investigative report of RSHA's 3rd office.[97]

A major document which enabled historians to accurately reconstruct the Generalplan Ost was a memorandum released on April 27, 1943, by Erhard Wetzel, director of the NSDAP Office of Racial Policy, entitled "Opinion and thoughts on the master plan for the East of the Reichsführer SS".[98] Wetzel's memorandum was a broad elaboration of the Generalplan Ost proposal.[99][40] It came to light only in 1957.[100] Wetzel's report has enabled attempts to re-construct the document on GPO prepared by RSHA's 3rd office.[97]

The extermination document for the Slavic people of Eastern Europe did survive the war and was quoted by Yale historian Timothy Snyder in 2010. It shows that ethnic Poles, Ukrainians and Czechs were primary targets of Generalplan Ost.[101] Belorussians were also a major target. According to the book "Kalkulierte Morde" ("Calculated massacres") published by Swiss historian Hans Christian Gerlach in 1999, Nazi Germany sought to exterminate the entire urban populace (approximately 2 million) and half the rural population (nearly 4.3 million) of Belorussia alone, through mass-starvations. These estimates were calculated by citing the notes of an anonymous author, whom Gerlach postulates to be Waldemar von Poletika, an agricultural scientist at Berlin University.[102]

Aftermath

One of the indictment charges at the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the S.S. officer responsible for the transportation aspects of the Final Solution, was that he was responsible for the deportation of 500,000 Poles. Eichmann was convicted on all 15 counts.[103] Poland's Supreme National Tribunal stated that "the wholesale extermination was first directed at Jews and also at Poles and had all the characteristics of genocide in the biological meaning of this term."[104]

Nazi savagery against Soviet prisoners of war, which resulted in the deaths of approximately 3.3 million captured Soviet detainees, was denounced by the Nuremberg tribunal as a "crime against humanity".[105] According to historian Norman Naimark:

"If the awful counterfactual of a Nazi victory had come to pass, not just Soviet soldiers, but Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians would surely have shared the fate of the Poles and been eliminated culturally and ethnically as distinct peoples and nations. Genocidal actions against those peoples would have been completed."

— The Cambridge World History of Genocide, Volume 3 (2023), [105]

See also

- World War II casualties of the Soviet Union

- World War II casualties of Poland

- A-A line, military goal of Operation Barbarossa

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Barbarossa decree

- Chronicles of Terror

- Einsatzgruppen

- Expulsion of Poles by Nazi Germany

- Holocaust victims

- Hunger Plan to seize food from the Soviet Union

- Nazi crimes against the Polish nation

- Expulsion of Poles by Nazi Germany

- Nazi crimes against Soviet POWs

- Nazism and race

- Racial policy of Nazi Germany

- World War II evacuation and expulsion

- Forced labor under German rule during World War II

- Bibliography of the Holocaust § Primary Sources

Footnotes

- ^ Giaccaria, Paolo; Minca, Claudio, eds. (2016). Hitler's Geographies: The Spatialities of the Third Reich. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 29, 30, 33, 34, 37, 110. ISBN 978-0-226-27442-3.

- ^ Masiuk, Tony (20 March 2019). "Hitler's Manifest Destiny: Nazi Genocide, Slavery, and Colonization in Slavic Eastern Europe". Academia.edu. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022.

Hitler's vision was to recreate and remodel this kind of colonial process. In particular, he envisioned a colonization alike to America's Manifest Destiny, but instead occurring in Eastern Europe, whereby the Volga river would become the Mississippi, and the Slavs would become the Native Americans and "fight like Indians".

- ^ "Lebensraum". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018.

For the Germans, eastern Europe represented their "Manifest Destiny." Hitler and other Nazi thinkers drew direct comparisons to American expansion in the West. During one of his famous "table talks," Hitler decreed that "there's only one duty: to Germanize this country [Russia] by the immigration of Germans and to look upon the natives as Redskins."

- ^ J. Barnes, Trevor (2016). "9: A Morality Tale of Two Location Theorists in Hitler's Germany: Walter Christaller and August Lösch". In Giaccaria, Paolo; Minca, Claudio (eds.). Hitler's Geographies: The Spatialities of the Third Reich. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-226-27442-3.

- ^ a b c Lens (2019).

- ^ Naimark 2023, pp. 367, 368.

- ^ Moses, A. Dirk, ed. (2008). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Berghahn Books. p. 20.

As a matter of fact, Hitler wanted to commit Genocide against the Slavic peoples, in order to colonize the East

- ^ a b c Masiuk, Tony (20 March 2019). "Hitler's Manifest Destiny: Nazi Genocide, Slavery, and Colonization in Slavic Eastern Europe". Academia.edu. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022.

- ^ Barenberg, Alan (2017). "27: Forced Labor in Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union". In Eltis, David; L. Engerman, Stanley; Drescher, Seymour; Richardson, David (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Slavery. Vol. 4. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 640, 650. doi:10.1017/9781139046176.028. ISBN 978-0-521-84069-9.

- ^ WISSENSCHAFT - PLANUNG - VERTREIBUNG. Archived 2021-07-26 at the Wayback Machine Der Generalplan Ost der Nationalsozialisten· Eine Ausstellung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft © 2006

- ^ "Dietrich Eichholtz»Generalplan Ost« zur Versklavung osteuropäischer Völker" (PDF) (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-14.

- ^ a b Yad Vashem. "Generalplan Ost" (PDF).

- ^ "Lebensraum". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2019-06-23.

- ^ Naimark 2023, pp. 358–377.

- ^ "Generalplan Ost (General Plan East). The Nazi evolution in German foreign policy. Documentary sources". World Future Fund.

- ^ "Wissenschaft, Planung, Vertreibung - Der Generalplan Ost der Nationalsozialisten". Eine Ausstellung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (in German). 2006. Archived from the original on 2021-07-26. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- ^ Kay, Alex J. (2006). Exploitation, Resettlement, Mass Murder: Political and Economic Planning for German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1940-1941. Oxford, UK: Berghahn Books. pp. 99–102. ISBN 1-84545-186-4.

- ^ Browning, Christopher R. (2010). "20: The Nazi Empire". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 418–420. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- ^ a b Eichholtz, Dietrich (September 2004). ""Generalplan Ost" zur Versklavung osteuropäischer Völker" [Generalplan Ost for the enslavement of East European peoples] (downloadable PDF). Utopie Kreativ (in German). 167: 800–8 – via Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2011). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. London, UK: Vintage Books. pp. 160–163. ISBN 9780099551799.

- ^ a b Rein, Leonid (2011). "3: German Policies in Byelorussia (1941–1944)". The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ a b Naimark 2023, pp. 359.

- ^ Rein, Leonid (2011). "4: Byelorussian "State-Building": Political Collaboration in Byelorussia". The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. pp. 138, 180. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf (1939). "XIV: Germany's policy in Eastern Europe". Mein Kampf. Hurst & Blackett Ltd. pp. 500, 501.

- ^ a b c d e Browning (2007), pp. 240–1

- ^ "Die Entwicklung des Generalplans Ost" [The development of the General Plan East]. Eine Ausstellung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (in German). 2006. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021.

- ^ Tooze 2007, p. 472.

- ^ Tooze 2007, p. 473.

- ^ Giaccaria, Paolo; Minca, Claudio, eds. (2016). Hitler's Geographies: The Spatialities of the Third Reich. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 189, 213. ISBN 978-0-226-27442-3.

- ^ Barenberg, Alan (2017). "27: Forced Labor in Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union". In Eltis, David; L. Engerman, Stanley; Drescher, Seymour; Richardson, David (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Slavery. Vol. 4. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. p. 640. doi:10.1017/9781139046176.028. ISBN 978-0-521-84069-9.

- ^ Zimmerer, Jürgen (2023). "Colonialism and the Holocaust: Towards an Archaeology of Genocide". From Windhoek to Auschwitz?: Reflections on the Relationship between Colonialism and National Socialism (English ed.). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Oldenbourg. p. 141. doi:10.1515/9783110754513. ISBN 978-3-11-075420-9. ISSN 2941-3095. LCCN 2023940036.

- ^ a b Zimmerer, Jürgen (2023). From Windhoek to Auschwitz?: Reflections on the Relationship between Colonialism and National Socialism (English ed.). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Oldenbourg. p. 314. doi:10.1515/9783110754513. ISBN 978-3-11-075420-9. ISSN 2941-3095. LCCN 2023940036.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gumkowski, Janusz; Leszczynski, Kazimierz (1961). Poland under Nazi Occupation. Warsaw: Polonia Publishing House. OCLC 456349. See excerpts in "Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe". Holocaust Awareness Committee - History Department, Northeastern University. Archived from the original on 2011-11-25.

- ^ a b c d e f Misiunas & Taagepera (1993), p. 48–9

- ^ The Ashgate Research Companion to Imperial Germany edited by Matthew Jefferies Colonialism and Genocide by Jurgent Zimmerer page 437 Routledge 2015 discussions about the Generalplan Ost – which foresaw up to 70 million Russians being deported to Siberia and left to perish.

- ^ Zimmerer, Jürgen (2023). From Windhoek to Auschwitz?: Reflections on the Relationship between Colonialism and National Socialism (English ed.). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Oldenbourg. p. 314. doi:10.1515/9783110754513. ISBN 978-3-11-075420-9. ISSN 2941-3095. LCCN 2023940036.

Under this master plan, up to 80 million Russians were to be driven out of the newly established German colonial lands into the areas beyond the Urals, whereby the planners were well aware that several million (up to 30 million, to be more exact) would not survive this.

- ^ Smith, David J. (2001). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 978-041526728-1.

- ^ The Third Reich and Ukraine, Volodymyr Kosyk P. Lang, 1993 page 231

- ^ "Forced Labor under the Third Reich - Part One" (PDF). Nathan Associates Inc. 2015-08-24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-08-24. Retrieved 2019-08-08.

- ^ a b c d Gellately, Robert (1996). "Reviewed Works: Vom Generalplan Ost zum Generalsiedlungsplan by Czeslaw Madajczyk; Der 'Generalplan Ost'. Hauptlinien der nationalsozialistischen Planungs- und Vernichtungspolitik by Mechtild Rössler, Sabine Schleiermacher". Central European History. 29 (2): 270–274. doi:10.1017/S0008938900013170. ISSN 0008-9389. JSTOR 4546609. References: Madajczyk (1994); Rössler & Scheiermacher (1993).

- ^ Madajczyk, Czesław (1980). "Die Besatzungssysteme der Achsenmächte. Versuch einer komparatistischen Analyse" [Occupation modalities of the Axis powers. A possible comparative analysis]. Studia Historiae Oeconomicae. 14: 105–22. doi:10.14746/sho.1979.14.1.008. See also Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Ueberschär, Gerd R., eds. (2008). Hitler's War in the East, 1941-1945: A Critical Assessment. Berghahn. ISBN 978-1-84545-501-9. Google Books.

- ^ Rein, Leonid (2011). "4: Byelorussian "State-Building": Political Collaboration in Byelorussia". The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. p. 280. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ a b Schmuhl, Hans-Walter (2008). The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, 1927–1945. Crossing boundaries. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science. Vol. 259. Springer Netherlands. pp. 348–9. ISBN 978-90-481-7678-6.

- ^ a b Connelly, J. (1999). "Nazis and Slavs: From Racial Theory to Racist Practice". Central European History. 32 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1017/S0008938900020628. JSTOR 4546842. PMID 20077627. S2CID 41052845.

- ^ Rössler, Mechtild (2016). "8: Applied Geography and Area Research in Nazi Society: Central Place Theory and Planning, 1933– 1945". In Giaccaria, Paolo; Minca, Claudio (eds.). Hitler's Geographies: The Spatialities of the Third Reich. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 189, 190. ISBN 978-0-226-27442-3.

- ^ Mechtild, Rössler (2016). "8: Applied Geography and Area Research in Nazi Society: Central Place Theory and Planning, 1933– 1945". In Giaccaria, Paolo; Minca, Claudio (eds.). Hitler's Geographies: The Spatialities of the Third Reich. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 189, 190. ISBN 978-0-226-27442-3.

- ^ Rein, Leonid (2011). "7: Collaboration in the Politics of Repression". The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. p. 280. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ Beever, Antony (2007). Stalingrad. New York, New York: Penguin Books. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-14-192610-0.

- ^ Rein, Leonid (2011). The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. pp. 326, 360. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ a b Rein, Leonid (2011). The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ "Kartenskizze eines zukünftigen Europa unter deutscher Herrschaft" [Sketch map of a future Europe under German rule]. Deutsches Historisches Museum. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017.

- ^ Rein, Leonid (2011). The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. pp. 326, 360, 393, 394. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ Sergeant, Maggie (2005). Kitsch & Kunst: Presentations of a Lost War. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang. p. 47. ISBN 3-03910-512-4.

- ^ Rein, Leonid (2011). The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. pp. 257, 258, 395. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ W. Borejsza, Jerzy (2017). A ridiculous hundred million Slavs : Concerning Adolf Hitler's world-view. Translated by French, David. Warsaw, Poland: Instytut Historii PAN. pp. 25, 139, 140. ISBN 978-83-63352-88-2.

- ^ "Obozy pracy na terenie Gminy Hańsk" [Labor camps in Gmina Hańsk] (in Polish). hansk.info. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ Heinemann, Isabel (1999). Rasse, Siedlung, deutsches Blut. Das Rasse- und Siedlungshauptamt der SS und die rassenpolitische Neuordnung Europas. Wallstein Verlag. p. 370. ISBN 3892446237.

- ^ a b c Rein, Leonid (2011). The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ Fritz 2011, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Fritz 2011, pp. 260, 261.

- ^ Fritz 2011, pp. 259–261, 334.

- ^ Rozett, Robert; Spector, Shmuel (2013). "Generalplan Ost". Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. New York: Routledge. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-57958-307-1.

- ^ Fritz 2011, p. 334.

- ^ Zimmerer, Jürgen (2023). From Windhoek to Auschwitz?: Reflections on the Relationship between Colonialism and National Socialism (English ed.). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Oldenbourg. pp. 141, 151. doi:10.1515/9783110754513. ISBN 978-3-11-075420-9. ISSN 2941-3095. LCCN 2023940036.

- ^ Zimmerer, Jürgen (2023). From Windhoek to Auschwitz?: Reflections on the Relationship between Colonialism and National Socialism (English ed.). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Oldenbourg. pp. 31, 131, 171, 172, 184, 237, 238, 297, 298, 300. doi:10.1515/9783110754513. ISBN 978-3-11-075420-9. ISSN 2941-3095. LCCN 2023940036.

- ^ Raun, Toivo U. (2002). Estonia and the Estonians (2nd updated ed.). Stanford CA: Hoover Institution Press. pp. 160–4. ISBN 0817928537.

- ^ Rein, Leonid (2011). "1: Collaboration in Occupied Europe: Theoretical Overview". The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. pp. 25, 26, 32. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ Rein, Leonid (2011). The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ Nicholas, Lynn H. (2011). Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web. Knopf Doubleday. p. 194. ISBN 978-0307793829.

- ^ Berghahn, Volker R. (1999). "Germans and Poles 1871–1945". In Bullivant, K.; Giles, G.J.; Pape, W. (eds.). Germany and Eastern Europe: Cultural Identities and Cultural Differences. Rodopi. pp. 15–34. ISBN 9042006889.

- ^ Weinberg, Gerhard L. (2005). Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leaders. Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-052185254-8.

- ^ Cecil, Robert (1972). The Myth of the Master Race: Alfred Rosenberg and Nazi Ideology. New York City: Dodd, Mead & Co. p. 19. ISBN 0-396-06577-5.

- ^ Sontheimer, Michael (27 May 2011). "When We Finish, Nobody Is Left Alive". Spiegel Online.

- ^ Trevor-Roper, H.R., ed. (2007). "The Mind of Adolf Hitler". Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944. Translated by Cameron, Norman; Stevens, R.H. (New Updated ed.). New York, USA: Enigma Books. pp. xxviii, xxix. ISBN 978-1-929631-66-7.

- ^ Fritz 2011, p. 93.

- ^ Moore, Bob (2022). "8: War of Annihilation: Russian Prisoners of War on the Eastern Front 1941‒1942". Prisoners of War: Europe: 1939-1956. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 206, 207.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2011). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. London, UK: Vintage Books. p. 251. ISBN 9780099551799.

- ^ "Nazi persecution of Soviet prisoners of war". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 9 March 2024.

- ^ Rozett, Robert; Spector, Shmuel (2013). "Generalplan Ost". Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. New York: Routledge. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-57958-307-1.

During the war, many of Nazis' activities were carried out with Generalplan Ost in mind. They massacred millions of Jews in Eastern Europe, in addition to millions to Soviet prisoners of war.

- ^ Roberts, Priscilla, ed. (2012). World War II: The Essential Reference Guide. California, USA: ABC-CLIO, LLC. pp. 208, 209. ISBN 978-1-61069-101-7.

- ^ Browning, Christopher R. (2010). "20: The Nazi Empire". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- ^ Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-8020-7820-9.

- ^ Dawidowicz, Lucy (1986). The War Against the Jews. New York: Bantam Books. p. 403. ISBN 0-553-34302-5.

- ^ Alfred J. Rieber (2003). "Civil Wars in the Soviet Union" (PDF). pp. 133, 145–147. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2022. Slavica Publishers.

- ^ Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. p. 679. ISBN 978-0802078209.

- ^ Dawidowicz, Lucy S. (1986). The war against the Jews, 1933–1945. New York: Bantam Books. p. 403. ISBN 0-553-34302-5.

- ^ Kruglov, Alexander Iosifovich. "ХРОНИКА ХОЛОКОСТА В УКРАИНЕ 1941–1944 гг" (PDF). holocaust-ukraine.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-09.

To this number of victims should be added Jews who died in captivity, as well as Jews who were exterminated on the territory of Russia (mainly in the North Caucasus), where they evacuated in 1941 and where they were caught by the Germans in 1942. Number of Jews who perished can be estimated at 1.6 million.

- ^ D. Snyder, Timothy; Brandon, Ray (30 May 2014). Stalin and Europe: Imitation and Domination, 1928–1953. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939259-9.

Approximately 1.5 million of the approximately 5.7 million Jews murdered during the Holocaust came from within the borders of what is today Ukraine – Dieter Pohl

- ^ Hans-Walter Schmuhl. The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, 1927–1945: crossing boundaries. Volume 259 of Boston studies in the philosophy of science. Coutts MyiLibrary. SpringerLink Humanities, Social Science & LawAuthor. Springer, 2008. ISBN 9781402065996, p. 348–349

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- ^ Robert Gellately. Reviewed works: Vom Generalplan Ost zum Generalsiedlungsplan by Czeslaw Madajczyk. Der "Generalplan Ost." Hauptlinien der nationalsozialistischen Planungs- und Vernichtungspolitik by Mechtild Rössler; Sabine Schleiermacher. Central European History, Vol. 29, No. 2 (1996), pp. 270–274

- ^ "Russia's War on Ukraine". 5 March 2014. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Berkhoff (2004), p. 45.

- ^ Berkhoff (2004), p. 166.

- ^ a b "Axis Invasion Of Yugoslavia". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ Poprzeczny, Joseph (2004). Odilo Globocnik, Hitler's Man in the East. McFarland. p. 186. ISBN 0-7864-1625-4.

- ^ a b Rein, Leonid (2011). "3: German Policies in Byelorussia (1941–1944)". The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ Wetzel (1942).

- ^ Weiss-Wendt, Anton (2010). Eradicating Differences: The Treatment of Minorities in Nazi-Dominated Europe. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 978-1443824491.

- ^ Madajczyk (1962).

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books. p. 160.

- ^ Rein, Leonid (2011). "3: German Policies in Byelorussia (1941–1944)". The Kings and the Pawns: Collaboration in Byelorussia during World War II. New York, USA: Berghahn Books. pp. 91, 92. ISBN 978-1-84545-776-1.

- ^ Korbonski, Stefan (1981). The Polish Underground State: A Guide to the Underground, 1939-1945. Hippocrene Books. pp. 120, 137–8. ISBN 978-088254517-2.

- ^ Law-Reports of Trials of War Criminals, The United Nations War Crimes Commission, volume VII, London, His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1948, Case no. 37: The Trial of Hauptsturmführer Amon Leopold Goeth, p. 9: "The Tribunal accepted these contentions and in its Judgment against Amon Goeth stated the following: 'His criminal activities originated from general directives that guided the criminal Fascist-Hitlerite organization, which under the leadership of Adolf Hitler aimed at the conquest of the world and at the extermination of those nations, which stood in the way of the consolidation of its power.... The policy of extermination was in the first place directed against the Jewish and Polish nations.... This criminal organization did not reject any means of furthering their aim of destroying the Jewish nation. The wholesale extermination of Jews and also of Poles had all the characteristics of genocide in the biological meaning of this term.'"

- ^ a b Naimark 2023, pp. 377.

References

- Aly, Götz; Heim, Susanne (2003). Architects of Annihilation: Auschwitz and the Logic of Destruction. Phoenix. The General Plan for the East. ISBN 1-84212-670-9 – via Google Books.

- Berenbaum, Michael, ed. (1990). A Mosaic of Victims: Non-Jews Persecuted and Murdered by the Nazis. NYUP. ISBN 1-85043-251-1.

- Berkhoff, Karel C. (2004). Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule. Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-01313-1.

- Browning, Christopher R. (2007). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942. U of Nebraska Press. Generalplan Ost: The Search for a Final Solution through Expulsion. ISBN 978-0803203921.

- Fritz, Stephen G. (2011). Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East. University Press of Kentucky. Generalplan Ost (General plan for the east). ISBN 978-0813140506 – via Google Books.

- Koehl, Robert L. (1957). Rkfdv: German Resettlement and Population Policy 1939–1945: A History of the Reich Commission for the Strengthening of Germandom. Harvard University Press. OCLC 906064851.

- Madajczyk, Czesław (1962). "General Plan East. Hitler's Master Plan for expansion". Polish Western Affairs. III (2). World Future Fund. Resources: Wetzel (1942); Meyer-Hetling (1942). Note: After World War II, it was thought, that the memorandum itself had been lost. The first information of its content was given in Koehl (1957), p. 72.

- Madajczyk, Czesław, ed. (1994). Vom Generalplan Ost zum Generalsiedlungsplan: Dokumente (in German). de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3598232244.

- Rössler, Mechtild; Scheiermacher, Sabine, eds. (1993). Der 'Generalplan Ost': Hauptlinien der nationalsozialistischen Plaungs-und Vernichtungspolitik (in German). Akademie-Verlag. ISBN 978-3050024455.

- Russian Academy of Science (1995). Liudskie poteri SSSR v period vtoroi mirovoi voiny:sbornik statei [Human losses of the USSR in the period of WWII: collection of articles.] (in Russian). Sankt-Petersburg: Institut Rossiiskoi istorii RAN. ISBN 5-86789-023-6.

- Snyder, Timothy (2012). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books. Generalplan Ost. ISBN 978-0465002399.

- Wildt, Michael (2008). Generation of the unbound: the leadership corps of the Reich Security Main Office. Wallstein Verlag. Weltanschauung. ISBN 978-3835302907 – via Google Books.

- Naimark, Norman (2023). "15: The Nazis and the Slavs - Poles and Soviet Prisoners of War". In Kiernan, Ben; Lower, Wendy; Naimark Norman; Straus, Scott (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Vol. 3: Genocide in the Contemporary Era, 1914–2020. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 359, 377. doi:10.1017/9781108767118. ISBN 978-1-108-48707-8.

- Tooze, Adam (2007) [2006]. The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-141-00348-1.

- Lens, Lennart (2019). The Forgotten Holocaust: The systematic genocide on the Slavic people by the Nazis during the Second World War (BA thesis). Archived from the original on 25 June 2021 – via Leiden University.

- Misiunas, Romuald J.; Taagepera, Rein (1993) [1983]. The Baltic States: Years of Dependence, 1940-80 (Expanded and updated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-052008228-1 – via Internet Archive.

Primary sources

- Meyer-Hetling, Konrad (June 1942). 'Generalplan Ost'. Rechtliche, wirtschaftliche und räumliche Grundlagen des Ostaufbaues (in German). Under supervision of Heinrich Himmler.

- Wetzel, Erhard (27 April 1942). Stellungnahme und Gedanken zum Generalplan Ost des Reichsführers S.S. [Opinion and thoughts on the master plan for the East of the Reichsführer SS] (Memorandum). pp. 297–324. In "Dokumentation - Der Generalplan Ost" (PDF). Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. 6 (3). Institut für Zeitgeschichte: 281–325. 1958.

Further reading

- Bakoubayi Billy, Jonas: Musterkolonie des Rassenstaats: Togo in der kolonialpolitischen Propaganda und Planung Deutschlands 1919-1943, J.H.Röll-Verlag, Dettelbach 2011, ISBN 978-3-89754-377-5. (in German)

- Eichholtz, Dietrich. "Der Generalplan Ost." Über eine Ausgeburt imperialistischer Denkart und Politik, Jahrbuch für Geschichte, Volume 26, 1982. (in German)

- Heiber, Helmut. "Der Generalplan Ost." Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Volume 3, 1958. (in German)

- Kamenetsky, Ihor (1961). Secret Nazi Plans for Eastern Europe: A Study of Lebensraum Policies. New York City: Bookman Associates.

- Madajczyk, Czesław. Die Okkupationspolitik Nazideutschlands in Polen 1939-1945, Cologne, 1988. OCLC 473808120 (in German)

- Madajczyk, Czesław. Generalny Plan Wschodni: Zbiór dokumentów, Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce, Warszawa, 1990. OCLC 24945260 (in Polish)

- Roth, Karl-Heinz, "Erster Generalplan Ost." (April/May 1940) von Konrad Meyer, Dokumentationsstelle zur NS-Sozialpolitik, Mittelungen, Volume 1, 1985. (in German)

- Szcześniak, Andrzej Leszek. Plan Zagłady Słowian. Generalplan Ost, Polskie Wydawnictwo Encyklopedyczne, Radom, 2001. ISBN 8388822039 OCLC 54611513 (in Polish)

- Wildt, Michael. "The Spirit of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA)." Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions (2005) 6#3 pp. 333–349. Full article available with purchase.

External links

- Berlin-Dahlem (May 28, 1942). Full text of the original German Generalplan Ost document. Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine "Legal, economic and spatial foundations of the East." Digitized copy of the 100-page version from the Bundesarchiv Berlin-Licherfelde. (in German)

- Worldfuturefund.org: Documentary sources regarding Generalplan Ost

- Dac.neu.edu: Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe

- Der Generalplan Ost der Nationalsozialisten. Archived 2021-06-13 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- Deutsches Historisches Museum (2009), Berlin, Übersichtskarte: Planungsszenarien zur "völkischen Flurbereinigung" in Osteuropa.

- Generalplan Ost

- Eastern Front (World War II)

- Nazi colonies in Eastern Europe

- Planning the Holocaust

- Ethnic cleansing in Europe

- Forced migrations in Europe

- Anti-Slavic sentiment

- Antisemitic attacks and incidents

- Anti-Estonian sentiment

- Anti-Latvian sentiment

- Anti-Lithuanian sentiment

- Anti-Polish sentiment

- Anti-Russian sentiment

- Anti-Ukrainian sentiment

- German colonial empire

- Holocaust terminology

- Heinrich Himmler

- Nazi SS

- The Holocaust

- The Holocaust in Belarus

- The Holocaust in Estonia

- The Holocaust in Latvia

- The Holocaust in Lithuania

- The Holocaust in Poland

- The Holocaust in Russia

- The Holocaust in Ukraine

- Axis powers

- The Holocaust in the Soviet Union

- Nazi war crimes in the Soviet Union

- Genocide of indigenous peoples in Europe

- Germanization

- Forced migrations during World War II