Economy of fascist Italy

The economy of Fascist Italy refers to the economy in the Kingdom of Italy under Fascism between 1922 and 1943. Italy had emerged from World War I in a poor and weakened condition and, after the war, suffered inflation, massive debts and an extended depression. By 1920, the economy was in a massive convulsion, with mass unemployment, food shortages, strikes, etc. That conflagration of viewpoints can be exemplified by the so-called Biennio Rosso (Two Red Years).

Background

[edit]There were some economic problems in Europe like inflation in the aftermath of the war. The consumer price index in Italy continued to increase after 1920 but Italy did not experience hyper-inflation on the level of Austria, Poland, Hungary, Russia and Germany. The costs of the war and postwar reconstruction contributed to inflationary pressure. The changing political attitudes of the post-war period and rise of a working class was also a factor and Italy was one of several countries where there was a disagreement about the tax burden.[1]

Fascist economic policy

[edit]Benito Mussolini came to power in 1922 under a parliamentary coalition until the National Fascist Party seized control and ushered in a one-party dictatorship by early 1925. The growth in Mussolini’s popularity to the extent of becoming a national leader was gradual as would be expected for a leader of any fascist movement.[2] The doctrine only succeeded in Italy because the public was just as enthusiastic for change as much as Mussolini was committed to doing away with the liberal doctrines and Marxism in the country. Therefore, he would later write (with the help of Giovanni Gentile) and distribute The Doctrine of Fascism to the Italian society, which ended up being the basis of the Fascist agenda throughout Mussolini’s dictatorship.[3] Mussolini did not simply thrust himself into the dictatorship position, but rather rose gradually based on his understanding of the existing support for his ideas in the country.[4]

Before the dictatorship era, Mussolini tried to transform the country's economy along fascist ideology, at least on paper. In fact, he was not an economic radical, nor did he seek a free-hand in the economy. The Fascist Party held a minority faction of only three positions in the cabinet, excluding Mussolini;[5] and providing other political parties more independence. During the coalition period, Mussolini appointed a classical liberal economist, Alberto De Stefani, originally a stalwart leader in the Center Party as Italy’s Minister of Finance,[6] who advanced economic liberalism, along with minor privatization. Before his dismissal in 1925, Stefani "simplified the tax code, cut taxes, curbed spending, liberalized trade restrictions and abolished rent controls", where the Italian economy grew more than 20 percent, and unemployment fell 77 percent, under his influence.[7]

To proponents of the first view, Mussolini did have a clear economic agenda, both long and short-term, from the beginning of his rule. The government had two main objectives—to modernize the economy and to remedy the country's lack of strategic resources. Before the removal of Stefani, Mussolini's administration pushed the modern capitalistic sector in the service of the state, intervening directly as needed to create a collaboration between the industrialists, the workers and the state. The government moved toward resolving class conflicts in favour of corporatism. In the short term, the government worked to reform the widely abused tax system, dispose of inefficient state-owned industry, cut government costs and introduce tariffs to protect the new industries. However, these policies ended after Mussolini took dictatorial controls and terminated the coalition.

The lack of industrial resources, especially the key ingredients of the Industrial Revolution, was countered by the intensive development of the available domestic sources and by aggressive commercial policies—searching for particular raw material trade deals, or attempting strategic colonization. In order to promote trade, Mussolini pushed the Italian parliament to ratify an "Italo-Soviet political and economic agreement" by early 1923.[8] This agreement assisted Mussolini’s effort to have the Soviet Union officially recognized by Italy in 1924, the first Western nation to do so.[9] With the signing of the 1933 Treaty of Friendship, Nonaggression, and Neutrality with the Soviet Union, Fascist Italy became a major trading partner with Joseph Stalin's Russia, exchanging natural resources from Soviet Russia for technical assistance from Italy, which included the fields of aviation, automobile and naval technology.[10]

Although a disciple of the French Marxist Georges Sorel and the main leader of the Italian Socialist Party in his early years, Mussolini abandoned the theory of class struggle for class collaboration. Some fascist syndicalists turned to economic collaboration of the classes to create a "productivist" posture where "a proletariat of producers" would be critical to the "conception of revolutionary politics" and social revolution.[11] However, most fascist syndicalists instead followed the lead of Edmondo Rossoni, who favored combining nationalism with class struggle,[12] often displaying a hostile attitude towards capitalists. This anti-capitalist hostility was so contentious that in 1926 Rossoni denounced industrialists as "vampires" and "profiteers".[13]

Since Italy’s economy was generally undeveloped with little industrialization, fascists and revolutionary syndicalists, such as Angelo Oliviero Olivetti, argued that the Italian working class could not have the requisite numbers or consciousness "to make revolution".[14] They instead followed Karl Marx's admonition that a nation required "full maturation of capitalism as the precondition for socialist realization".[15] Under this interpretation, especially as expounded by Sergio Panunzio, a major theoretician of Italian fascism, "[s]yndicalists were productivists, rather than distributionists".[16] Fascist intellectuals were determined to foster economic development to enable a syndicalist economy to "attain its productive maximum", which they identified as crucial to "socialist revolution".[17]

Structural deficit, public works and social welfare

[edit]Referring to the economics of John Maynard Keynes as "useful introduction to fascist economics", Mussolini spent Italy into a structural deficit that grew exponentially.[18] In Mussolini’s first year as Prime Minister in 1922, Italy's national debt stood at Lit.93 billion. By 1934, Italian anti-fascist historian Gaetano Salvemini, estimated Italy's national debt had risen to Lit.149 billion.[19] In 1943, The New York Times put Italy’s national debt as Lit.406 billion.[20]

A former school teacher, Mussolini’s spending on the public sector, schools and infrastructure was considered extravagant. Mussolini "instituted a programme of public works hitherto unrivaled in modern Europe. Bridges, canals and roads were built, hospitals and schools, railway stations and orphanages; swamps were drained and land reclaimed, forests were planted and universities were endowed".[21] As for the scope and spending on social welfare programs, Italian fascism "compared favorably with the more advanced European nations and in some respect was more progressive".[22] When New York city politician Grover Aloysius Whalen asked Mussolini about the meaning behind Italian fascism in 1939, the reply was: "It is like your New Deal!".[23]

By 1925, the Fascist government had "embarked upon an elaborate program" that included food supplementary assistance, infant care, maternity assistance, general healthcare, wage supplements, paid vacations, unemployment benefits, illness insurance, occupational disease insurance, general family assistance, public housing and old age and disability insurance.[24] As for public works, Mussolini's administration "devoted 400 million lire of public monies" for school construction between 1922 and 1942, compared to only 60 million lire between 1862 and 1922.[25]

First steps

[edit]The Fascist government began its reign in an insecure position. Coming to power in 1922 after the March on Rome, it was a minority government until the 1923 Acerbo Law and the 1924 elections and it took until 1925, after the assassination of Giacomo Matteotti, to establish itself securely as a dictatorship.

Economic policy in the first few years was largely classical liberal, with the Ministry of Finance controlled by the old liberal Alberto De Stefani. The multiparty coalition government undertook a low-key laissez-faire program—the tax system was restructured (February 1925 law, 23 June 1927 decree-law and so on), there were attempts to attract foreign investment and establish trade agreements and efforts were made to balance the budget and cut subsidies.[26] The 10% tax on capital invested in banking and industrial sectors was repealed while the tax on directors and administrators of anonymous companies (SA) was cut down by half. All foreign capital was exonerated of taxes while the luxury tax was also repealed.[27] Mussolini also opposed municipalization of enterprises.[27]

The 19 April 1923 law transferred life insurance to private enterprise, repealing a 1912 law that created a State Institute for insurances, which had envisioned construction of state monopoly ten years later.[28] Furthermore, a 19 November 1922 decree suppressed the Commission on war profits while the 20 August 1923 law suppressed the inheritance tax inside the family circle.[27]

There was a general emphasis on what has been called productivism—national economic growth as a means of social regeneration and wider assertion of national importance.

Up until 1925, the country enjoyed modest growth, but structural weaknesses increased inflation and the currency slowly fell (Lit.90 to £1 stg in 1922, Lit.135 to £1 stg in 1925). In 1925, there was a great increase in speculation and short runs against the lira. The levels of capital movement became so great the government attempted to intervene. De Stefani was sacked, his program side-tracked and the Fascist government became more involved in the economy in step with the increased security of their power.

In 1925, the Italian state abandoned its monopoly on telephone infrastructure while the state production of matches was handed over to a private "Consortium of matches' productors".[28]

Furthermore, various banking and industrial companies were financially supported by the state. One of Mussolini's first acts was to fund the metallurgical trust Ansaldo to the height of Lit.400 million. Following a deflation crisis that started in 1926, banks such as the Banco di Roma, the Banco di Napoli and Banco di Sicilia were also assisted by the state.[29] In 1924, the Unione Radiofonica Italiana (URI) was formed by private entrepreneurs and part of the Marconi group and granted the same year a monopoly of radio broadcasts. URI became the RAI after the war.

Lending to the private sector increased at an annual rate of 23.8 percent: total net profits of joint-stock banks doubled, providing 'excellent opportunities for financial intermediaries.' When this period was halted, the burden of deflationary policies disproportionately fell on the workers and employees.[30]

Firmer intervention

[edit]The lira continued to decline into 1926. It can be argued that this was not a bad thing for Italy since it resulted in cheaper and more competitive exports and more expensive imports. However, the declining lira was disliked politically. Mussolini apparently saw it as "a virility issue" and the decline was an attack on his prestige. In the Pesaro Speech of 18 August 1926, he began the "Battle for the Lira". Mussolini made a number of strong pronouncements and set his position of returning the lira to its 1922 level against sterling, "Quota 90". This policy was implemented through an extended deflation of the economy as the country rejoined the gold standard, the money supply was reduced and interest rates were raised. This action produced a sharp recession, which Mussolini took up as a sign of his assertion of power over "troublesome elements"—a slap to both capitalist speculators and trade unions.

On a wider scale, the Fascist economic policy pushed the country towards the corporative state, an effort that lasted well into the war. The idea was to create a national community where the interests of all parts of the economy were integrated into a class-transcending unity. Some see the move to corporatism in two phases. First, the workers were brought to heel over 1925–1927. Initially, the non-fascist trade unions and later (less forcefully) the fascist trade unions were nationalized by Mussolini's administration and placed under state ownership.[31] Under this labour policy, Fascist Italy enacted laws to make union membership compulsory for all workers.[32] This was a difficult stage as the trade unions were a significant component of Italian fascism from its radical syndicalist roots and they were also a major force in Italian industry. The changes were embodied in two key developments. The Pact of the Vidoni Palace in 1925 brought the fascist trade unions and major industries together, creating an agreement for the industrialists to only recognise certain unions and so marginalise the non-fascist and socialist trade unions. The Syndical Laws of 1926 (sometimes called the Rocco Laws after Alfredo Rocco) took this agreement a step further as in each industrial sector there could be only one trade union and employers organisation. Labour had previously been united under Edmondo Rossoni and his General Confederation of Fascist Syndical Corporations, giving him a substantial amount of power even after the syndical laws, causing both the industrialists and Mussolini himself to resent him. Thereby, he was dismissed in 1928 and Mussolini took over his position as well.[33]

Only these syndicates could negotiate agreements, with the government acting as an "umpire". The laws made both strikes and lock-outs illegal and took the final step of outlawing non-fascist trade unions. Despite strict regimentation, the labour syndicates had the power to negotiate collective contracts (uniform wages and benefits for all firms within an entire economic sector).[34] Firms that broke contracts usually got away with it due to the enormous bureaucracy and difficulty in solving labour disputes, primarily due to the significant influence the industrialists had over labour affairs.

Employer syndicates had a considerable amount of power as well. Membership within these associations was compulsory and the leaders had the power to control and regulate production practices, distribution, expansion and other factors with their members. The controls generally favoured larger enterprises over small producers, who were dismayed that they had lost a significant amount of individual autonomy.[34]

Since the syndical laws kept capital and labour separate, Mussolini and other party members continued to reassure the public that this was merely a stop-gap and that all associations would be integrated into the corporate state at a later stage.

The corporative phase

[edit]From 1927, these legal and structural changes led into the second phase, the corporative phase. The Labour Charter of 1927 confirmed the importance of private initiative in organising the economy while still reserving the right for state intervention, most notably in the supposedly complete fascist control of worker hiring through state-mandated collective bargaining. In 1930, the National Council of Corporations was established and it was for representatives of all levels of the twenty-two key elements of the economy to meet and resolve problems. In practice, it was an enormous bureaucracy of committees that while consolidating the potential powers of the state resulted in a cumbersome and inefficient system of patronage and obstructionism. One consequence of the Council was the fact that trade unions held little to no representation whereas organized business, specifically organized industry (CGII), was able to gain a foothold over its competitors.

A key effect that the Council had on the economy was the rapid increase in cartels, especially the law passed in 1932, allowing the government to mandate cartelization. The dispute was sparked when several industrial firms refused CGII orders to cartelize, prompting the government to step in. Since the corporations cut across all sectors of production, mutual agreements and cartelization was a natural reaction. Hence in 1937, over two-thirds of cartels authorized by the state, many of which crossed sectors of the economy, had started after the founding of the Council, resulting in the noticeable increase in commercial-industrial cartelization. Cartels generally undermined the corporative agencies that were meant to ensure they operated according to Fascist principles and in the national interest, but the heads were able to show that cartel representatives had total control over the individual firms in the distribution of resources, prices, salaries and construction. Businessmen usually argued in favour of "collective self-regulation" being within Fascist ideological lines when forming cartels, subtly undermining corporative principles.[34]

Government intervention in industry was very uneven as large programs started, but with little overarching direction. Intervention began with the "Battle of the Grain" in 1925 when the government intervened following the poor harvest to subsidise domestic growers and limit foreign imports by increasing taxes. This reduced competition and created, or sustained, widespread inefficiencies. According to historian Denis Mack Smith (1981), "[s]uccess in this battle was [...] another illusory propaganda victory won at the expense of the Italian economy in general and consumers in particular", continuing that "[t]hose who gained were the owners of the Latifondia and the propertied classes in general [...] his policy conferred a heavy subsidy on the Latifondisti".[35]

Larger programs began in the 1930s with the Bonifica Integrale land reclamation program (or so-called "Battle for Land"), which was employing over 78,000 people by 1933; the Mezzogiorno policies to modernise southern Italy and attack the Mafia as per capita income in the south was still 40% below that of the north; the electrification of the railways and similar transport programs; hydroelectrical projects; and the chemical industry, automobiles and steel. There was also limited takeover of strategic areas, notably oil with the creation of Agip (Azienda Generale Italiana Petroli—General Italian Oil Company).

The Great Depression

[edit]The worldwide depression of the early 1930s hit Italy very hard starting in 1931. As industries came close to failure they were bought out by the banks in a largely illusionary bail-out—the assets used to fund the purchases were largely worthless. This led to a financial crisis peaking in 1932 and major government intervention. After the bankruptcy of the Austrian Kredit Anstalt in May 1931, Italian banks followed, with the bankruptcy of the Banco di Milano, the Credito Italiano and the Banca Commerciale. To support them, the state created three institutions funded by the Italian Treasure, with the first being the Sofindit in October 1931 (with a capital of Lit.500 million), which bought back all the industrial shares owned by the Banca Commerciale and other establishments in trouble. In November 1931 the IMI (with a capital of Lit.500 million) was also created and it issued five and one-half billion liras in state obligations as reimbursables in a period of ten years. This new capital was lent to private industry for a maximum period of ten years.

Finally, the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction (IRI) formed in January 1933 and took control of the bank-owned companies, suddenly giving Italy the largest industrial sector in Europe that used government-linked companies (GLC). At the end of 1933, it saved the Hydroelectric Society of Piemont, whose shares had fallen from Lit.250 liras to Lit.20—while in September 1934, the Ansaldo trust was again reconstituted under the authority of the IRI, with a capital of Lit.750 million. Despite this taking of control of private companies through (GLC), the Fascist state did not nationalize any company.[29]

Not long after the creation of the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction, Mussolini boasted in a 1934 speech to his Chamber of Deputies: "Three-quarters of the Italian economy, industrial and agricultural, is in the hands of the state".[36][37] As Italy continued to nationalize its economy, the IRI "became the owner not only of the three most important Italian banks, which were clearly too big to fail, but also of the lion’s share of the Italian industries".[38]

Mussolini's economic policies during this period would later be described as "economic dirigisme", an economic system where the state has the power to direct economic production and allocation of resources.[39] The economic conditions in Italy, including institutions and corporations gave Mussolini sufficient power to engage with them as he could.[40] Although there were economic issues in the country, the approaches used in addressing them in the fascist era included political intervention measures, which ultimately could not effectively solve the strife.[41] An already bad situation ended up being worse since the solutions presented were largely intended to increase political power as opposed to helping the affected citizens.[42] These measures played a critical role in aggravating the conditions of the great depression in Italy.

By 1939, Fascist Italy attained the highest rate of state ownership of an economy in the world other than the Soviet Union,[43] where the Italian state "controlled over four-fifths of Italy's shipping and shipbuilding, three-quarters of its pig iron production and almost half that of steel".[44] IRI also did rather well with its new responsibilities—restructuring, modernising and rationalising as much as it could. It was a significant factor in post-1945 development. However, it took the Italian economy until 1935 to recover the manufacturing levels of 1930—a position that was only 60% better than that of 1913.[citation needed]

After Depression

[edit]There is no evidence that Italy's standard of living, which is lowest of the major powers, has been raised one jot or tittle since Il Duce came to power.

— Life, 9 May 1938[45]

As Mussolini's ambitions grew, domestic policy was subsumed by foreign policy, especially the push for autarky after the 1935 invasion of Abyssinia and the subsequent trade embargoes. The push for independence from foreign strategic materials was expensive, ineffective and wasteful. It was achieved by a massive increase in public debt, tight exchange controls and the exchange of economic dynamism for stability.

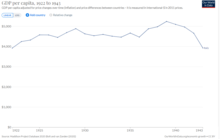

Recovery from the postwar slump had begun before Mussolini came to power, and later growth rates were comparatively weaker. From 1929 to 1939, the Italian economy grew by 16%, roughly half as fast as the earlier liberal period. Annual growth rates were 0.5% lower than prewar rates, and the annual rate of growth of value was 1% lower. Despite the efforts directed at industry, agriculture was still the largest sector of the economy in 1938, and only a third of total national income was derived from industry. Agriculture still employed 48% of the working population in 1936 (56% in 1921), industrial employment had grown only 4% over the period of fascist rule (24% in 1921 and 28% in 1936), and there was more growth in traditional than in modern industries. The rate of gross investment actually fell under Mussolini, and the move from consumer to investment goods was low compared to the other militaristic economies. Attempts to modernise agriculture were also ineffective. Land reclamation and the concentration on grains came at the expense of other crops, producing very expensive subsidised wheat while cutting more viable and economically rewarding efforts. Most evidence suggests that rural poverty and insecurity increased under fascism, and their efforts failed markedly to create a modern, rational agricultural system.

In the late 1930s, the economy was still too underdeveloped to sustain the demands of a modern militaristic regime. Production of raw materials was too small, and finished military equipment was limited in quantity and too often in quality. Although at least 10% of GDP, almost a third of government expenditure, began to be directed towards the armed services in the 1930s, the country was "spectacularly weak". Notably, the investment in the early 1930s left the services, especially the army, obsolete by 1940. Expenditures on conflicts from 1935 (such as commitments to the Spanish Civil War in 1936 to 1939 as well as the Italy-Albania War in 1939) caused little stockpiling to occur for the much greater World War II in 1940–1945.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Feinstein, Charles H. (1995). Banking, currency, and finance in Europe between the wars. Oxford University Press. pp. 18-20.

- ^ Paxton, Robert O. (1998). "The Five Stages of Fascism". The Journal of Modern History. 70 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1086/235001. ISSN 0022-2801. JSTOR 10.1086/235001. S2CID 143862302.

- ^ Berezin, Mabel (2018-10-18). Making the Fascist Self: The Political Culture of Interwar Italy. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501722141.

- ^ Marco, Tarchi (2000). Italy: Early Crisis and Fascist Takeover. Basingstoke: Springer. p. 297.

- ^ Howard M. Sachar, The Assassination of Europe 1918-1942: A Political History, University Press of Toronto Press, 2015, p. 48

- ^ Howard M. Sachar,The Assassination of Europe, 1918-1942: A Political History, Toronto: Canada, University of Toronto Press, 2015, p. 48

- ^ Jim Powell, “The Economic Leadership Secrets of Benito Mussolini,” Forbes, Feb. 22, 2012. Source: [1]

- ^ Xenia Joukoff Eudin and Harold Henry Fisher, Soviet Russia and the West, 1920-1927: A Documentary Survey, Stanford University Press, 1957, p. 190

- ^ Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism 1914—1945, University of Wisconsin Press, 1995 p. 223

- ^ Donald J. Stoker Jr. and Jonathan A. Grant, editors, Girding for Battle: The Arms Trade in a Global Perspective 1815-1940, Westport: CT, Praeger Publishers, 2003, page 180

- ^ A. James Gregor, Italian Fascism and Developmental Dictatorship, Princeton: NJ, Princeton University Press, 1979, pp. 59-60

- ^ Franklin Hugh Adler, Italian Industrialists from Liberalism to Fascism: The Political Development of the Industrial Bourgeoisie, 1906-1934, Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 311

- ^ Lavoro d'Italia, January 6, 1926

- ^ A. James Gregor, Italian Fascism and Developmental Dictatorship, Princeton: NJ, Princeton University Press, 1979, p. 55

- ^ A. James Gregor, Italian Fascism and Developmental Dictatorship, Princeton: NJ, Princeton University Press, 1979, p. 59

- ^ A. James Gregor, Italian Fascism and Developmental Dictatorship, Princeton: NJ, Princeton University Press, 1979, p. 60

- ^ A. James Gregor, Italian Fascism and Developmental Dictatorship, Princeton: NJ, Princeton University Press, 1979, pp. 60-61

- ^ James Strachey Barnes, Universal Aspects of Fascism, Williams and Norgate, London: UK, (1928) pp. 113-114

- ^ John T. Flynn, As We Go Marching, New York: NY, Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1944, p. 51. Also see “Twelve Years of Fascist Finance,” by Dr. Gaetano Salvemini Foreign Affairs, April 1935, Vol. 13, No. 3, p. 463

- ^ John T. Flynn, As We Go Marching, New York: NY, Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1944, p. 50. See New York Times, Aug. 8, 1943

- ^ Christopher Hibbert, Benito Mussolini: A Biography, Geneva: Switzerland, Heron Books, 1962, p. 56

- ^ A. James Gregor, Italian Fascism and Developmental Dictatorship, Princeton: NJ, Princeton University Press, 1979, p. 263

- ^ Grover Aloysius Whalen, Mr. New York: The Autobiography of Grover A. Whalen, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1955, p. 188

- ^ A. James Gregor, Italian Fascism and Developmental Dictatorship, Princeton: NJ, Princeton University Press, 1979, pp. 258-264

- ^ A. James Gregor, Italian Fascism and Developmental Dictatorship, Princeton: NJ, Princeton University Press, 1979, p. 260

- ^ Bel, Germà (September 2011). "The first privatisation: selling SOEs and privatising public monopolies in Fascist Italy (1922–1925)". Cambridge Journal of Economics. 35 (5): 937–956. doi:10.1093/cje/beq051.

- ^ a b c Daniel Guérin, Fascism and Big Business, Chapter IX, Second section, p.193 in the 1999 Syllepse Editions

- ^ a b Daniel Guérin, Fascism and Big Business, Chapter IX, First section, p.191 in the 1999 Syllepse Editions

- ^ a b Daniel Guérin, Fascism and Big Business, Chapter IX, Fifth section, p.197 in the 1999 Syllepse Editions

- ^ Gabbuti, Giacomo (2020-02-18). "A Noi! Income Inequality and Italian Fascism: Evidence from Labour and Top Income Shares".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Introduction to Modern Western Civilization, Bloomington: IN, iUnivere, 2011, p. 207

- ^ Gaetano Salvemini, The Fate of Trade Unions Under Fascism, Chap. 3: "Italian Trade Unions Under Fascism", 1937, p. 35

- ^ Roland Sarti, Fascism and the Industrial Leadership in Italy, 1919-40: A Study in the Expansion of Private Power Under Fascism, 1968

- ^ a b c Sarti, 1968

- ^ Denis Mack Smith (1981), Mussolini.

- ^ Gianni Toniolo, editor, The Oxford Handbook of the Italian Economy Since Unification, Oxford: UK, Oxford University Press, 2013, p. 59; Mussolini’s speech to the Chamber of Deputies was on May 26, 1934

- ^ Carl Schmidt, The Corporate State in Action, London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1939, pp. 153–76

- ^ Costanza A. Russo, “Bank Nationalizations of the 1930s in Italy: The IRI Formula”, Theoretical Inquiries in Law, Vol. 13:407 (2012), p. 408

- ^ Iván T. Berend, An Economic History of Twentieth-Century Europe, New York: NY, Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 93

- ^ Piero, Bini (2017). Business Cycles in Economic Thought: A history. Oxfordshire, UK: Taylor & Francis. p. 143.

- ^ Baker, David (2006-06-01). "The political economy of fascism: Myth or reality, or myth and reality?". New Political Economy. 11 (2): 227–250. doi:10.1080/13563460600655581. ISSN 1356-3467. S2CID 155046186.

- ^ Patricia, Calvin (2000). "The Great Depression in Europe, 1929-1939". History Review: 30.

- ^ Patricia Knight, Mussolini and Fascism: Questions and Analysis in History, New York: Routledge, 2003, p. 65

- ^ Martin Blinkhorn, Mussolini and Fascist Italy, 2nd edition, New York: NY, Routledge, 1991, p. 26

- ^ "Fascism / Inside Italy there is also "The Corporate State"". Life. 1938-05-09. p. 31. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Celli, Carlo. 2013. Economic Fascism: Primary Sources on Mussolini's Crony Capitalism. Axios Press.

- Mattesini, Fabrizio, and Beniamino Quintieri. "Italy and the Great Depression: An analysis of the Italian economy, 1929–1936." Explorations in Economic History (1997) 34#3 pp: 265-294.

- Mattesini, Fabrizio and Beniamino Quintieri. "Does a reduction in the length of the working week reduce unemployment? Some evidence from the Italian economy during the Great Depression." Explorations in Economic History (2006) 43#3 pp: 413-437.

- Zamagni, Vera. The economic history of Italy 1860-1990 (Oxford University Press, 1993).