Natural hydrogen

Natural hydrogen (known as white hydrogen, geologic hydrogen,[1] geogenic hydrogen,[2] or gold hydrogen), is hydrogen that is formed by natural processes[3][4] (as opposed to hydrogen produced in a laboratory or in industry). A closely related artificially produced form of hydrogen is green hydrogen which is produced from renewable energy sources such as wind or solar energy. Non-renewable forms of hydrogen include grey, brown, blue or black hydrogen which are obtained from the processing of fossil fuels.[5]

Natural hydrogen is believed to exist in economically viable concentrations and locations on every continent.[6] Natural hydrogen may be capable of supplying mankind's "projected global hydrogen demand for thousands of years," is non-polluting, may be available at significantly lower end user costs per therm than industrial hydrogen, and may be renewable.[7][8] Natural hydrogen has been identified in many source rocks in areas beyond the sedimentary basins where oil companies typically operate.[9][10][11]

History

[edit]In Adelaide Australia in the 1930’s local oil well drillers reported finding “vast amounts of high-purity hydrogen.” Unfortunately at the time, this hydrogen was viewed as merely a useless byproduct of the oil drilling industry, and no efforts were made to harvest this hydrogen. In 1987 in the village of Bourakébougou in Mali, Africa, a worker attempted to light his cigarette next to a certain water well, and the well unexpectedly caught fire.[12]

A local entrepreneur soon became interested in the possible economic value of this “burning well” and determined that the flames were produced by natural hydrogen seeping out of the well. A local petroleum company was soon hired to harvest and sell the hydrogen, and as of 2024, the villagers of Bourakébougou village continue to pay for their hydrogen. To date, the Malian hydrogen well remains as the world’s first and only economically successful hydrogen well.[12]

In recent years interest in natural hydrogen has increased as investors like Bill Gates and others have made millions of dollars in investments into the development of natural hydrogen wells in places like the US, France and Australia. In France, one petroleum company, Française De l’Énergie, has said that it aims to begin extracting hydrogen by 2027 or 2028.[6][12]

Natural hydrogen sources

[edit]Sources of natural hydrogen include:[13]

- degassing of deep hydrogen from Earth's crust and mantle;[14]

- reaction of water with ultrabasic rocks (serpentinisation);

- water in contact with reducing agents in Earth's mantle;

- weathering – water in contact with freshly exposed rock surfaces;

- decomposition of hydroxyl ions in the structure of minerals;

- natural water radiolysis;

- decomposition of organic matter;

- biological activity

Serpentinization is thought to produce approximately 80% of the world's hydrogen, especially as seawater interacts with iron- and magnesium-rich (ultramafic) igneous rocks in the ocean floor. Current models point towards radiolysis as the source of most other natural hydrogen.

Resources and reserves

[edit]According to the Financial Times, there are 5 trillion tons of natural hydrogen resources worldwide.[1] Most of this hydrogen is likely dispersed too widely to be economically recoverable, but the U.S. Geological Survey has reported that even a fractional recovery could meet global demand for hundreds of years. A discovery in Russia in 2008 suggests the possibility of extracting native hydrogen in geological environments.[citation needed] Resources have been identified in France,[15] Mali, the United States, and approximately a dozen other countries.[16]

In 2023 Pironon and de Donato announced the discovery of a deposit they estimated to be some 46 million to 260 million metric tons (several years worth of 2020s production).[17] In 2024, a natural deposit of helium and hydrogen was discovered in Rukwa, Tanzania.,[18] as well in Bulqizë, Albania.[19]

Midcontinent Rift System

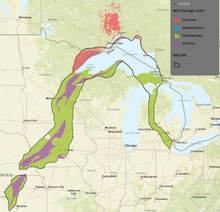

[edit]

White hydrogen could be found or produced in the Mid-continental Rift System at scale. Water could be pumped down to hot iron-rich rock to produce hydrogen for extraction.[20] Dissolving carbon dioxide in these fluids could allow for simultaneous carbon sequestration through carbonation of the rocks. The resulting hydrogen would be produced through a carbon-negative pathway and has been referred to as "orange" hydrogen.[21]

Geology

[edit]Natural hydrogen is generated from various sources. Many hydrogen emergences have been identified on mid-ocean ridges.[22] Serpentinisation occurs frequently in the oceanic crust; many targets for exploration include portions of oceanic crust (ophiolites) which have been obducted and incorporated into continental crust. Aulacogens such as the Midcontinent Rift System of North America are also viable sources of rocks which may undergo serpentinisation.[20]

Diagenetic origin (iron oxidation) in the sedimentary basins of cratons, notably are found in Russia.

Mantle hydrogen and hydrogen from radiolysis (natural electrolysis) or from bacterial activity are under investigation. In France, the Alps and Pyrenees are suitable for exploitation.[23] New Caledonia has hyperalkaline sources that show hydrogen emissions.[24]

Hydrogen is soluble in fresh water, especially at moderate depths as solubility generally increases with pressure. However, at greater depths and pressures, such as within the mantle,[25] the solubility decreases due to the highly asymmetric nature of mixtures of hydrogen and water.

Literature

[edit]Vladimir Vernadsky originated the concept of natural hydrogen captured by the Earth in the process of formation from the post-nebula cloud. Cosmogonical aspects were anticipated by Fred Hoyle. From 1960–2010, V.N. Larin developed the Primordially Hydridic Earth concept[26][dubious – discuss] that described deep-seated natural hydrogen prominence[27] and migration paths.

See also

[edit]- Green methanol - hydrogen and CO2 under heat and pressure make methanol

Bibliography

[edit]- Larin V.N. 1975 Hydridic Earth: The New Geology of Our Primordially Hydrogen-Rich Planet (Moscow: Izd. IMGRE) in Russian

- V.N. Larin (1993). Hydridic Earth, Polar Publishing, Calgary, Alberta. Hydridic Earth: the New Geology of Our Primordially Hydrogen-rich Planet

- Our Earth. V.N. Larin, Agar, 2005 (rus.) Наша Земля (происхождение, состав, строение и развитие изначально гидридной Земли)

- Lopez-Lazaro, Cristina; Bachaud, Pierre; Moretti, Isabelle; Ferrando, Nicolas (2019). "Predicting the phase behavior of hydrogen in NaCl brines by molecular simulation for geological applications". BSGF – Earth Sciences Bulletin. 190: 7. doi:10.1051/bsgf/2019008. S2CID 197609243.

- Gaucher, Éric C. (February 2020). "New Perspectives in the Industrial Exploration for Native Hydrogen". Elements: An International Magazine of Mineralogy, Geochemistry, and Petrology. 16 (1): 8–9. Bibcode:2020Eleme..16....8G. doi:10.2138/gselements.16.1.8.

- Gaucher, Éric C.; Moretti, I.; Gonthier, N.; Pélissier, N.; Burridge, G. (June 2023). "The place of natural hydrogen in the energy transition: A position paper". European Geologist Journal (55). doi:10.5281/zenodo.8108239. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- Deville, Eric; Prinzhofer, Alain (November 2016). "The origin of N2-H2-CH4-rich natural gas seepages in ophiolitic context: A major and noble gases study of fluid seepages in New Caledonia". Chemical Geology. 440: 139–147. Bibcode:2016ChGeo.440..139D. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.06.011.

- Gregory Paita, Master Thesis, Engie & Université de Montpellier.[title missing]

- Moretti I., Pierre H. Pour la Science, special issue in partnership with Engie, vol. 485; 2018. p. 28. N march. Moretti I, D'Agostino A, Werly J, Ghost C, Defrenne D, Gorintin L. Pour la Science, special issue, March 2018, vol 485, 24 25XXII_XXVI.[title missing]

- Prinzhofer, Alain; Moretti, Isabelle; Françolin, Joao; Pacheco, Cleuton; D'Agostino, Angélique; Werly, Julien; Rupin, Fabian (March 2019). "Natural hydrogen continuous emission from sedimentary basins: The example of a Brazilian H2-emitting structure" (PDF). International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 44 (12): 5676–5685. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.01.119. S2CID 104328822.

- Larin, Nikolay; Zgonnik, Viacheslav; Rodina, Svetlana; Deville, Eric; Prinzhofer, Alain; Larin, Vladimir N. (September 2015). "Natural Molecular Hydrogen Seepage Associated with Surficial, Rounded Depressions on the European Craton in Russia". Natural Resources Research. 24 (3): 369–383. Bibcode:2015NRR....24..369L. doi:10.1007/s11053-014-9257-5. S2CID 128762620.

- Zgonnik, Viacheslav; Beaumont, Valérie; Deville, Eric; Larin, Nikolay; Pillot, Daniel; Farrell, Kathleen M. (December 2015). "Evidence for natural molecular hydrogen seepage associated with Carolina bays (surficial, ovoid depressions on the Atlantic Coastal Plain, Province of the USA)". Progress in Earth and Planetary Science. 2 (1): 31. Bibcode:2015PEPS....2...31Z. doi:10.1186/s40645-015-0062-5. S2CID 55277065.

- Prinzhofer, Alain; Tahara Cissé, Cheick Sidy; Diallo, Aliou Boubacar (October 2018). "Discovery of a large accumulation of natural hydrogen in Bourakébougou (Mali)". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 43 (42): 19315–19326. Bibcode:2018IJHE...4319315P. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.08.193. S2CID 105839304.

- Zgonnik, Viacheslav (1 April 2020). "The occurrence and geoscience of natural hydrogen: A comprehensive review". Earth-Science Reviews. 203: 103140. Bibcode:2020ESRv..20303140Z. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103140. S2CID 213202508.

- Prinzhofer, Alain; Deville, Éric (2015). Hydrogène naturel, la prochaine révolution énergétique. Humensis. ISBN 978-2-410-00335-2. OCLC 1158938704.

- Moretti, Isabelle (22 May 2020). "L'hydrogène naturel : curiosité géologique ou source d'énergie majeure dans le futur ?". Connaissance des énergies (in French).

- Trégouët, René (17 July 2020). "L'hydrogène naturel pourrait devenir une véritable source d'énergie propre et inépuisable..." RT Flash (in French).

- Rigollet, Christophe; Prinzhofer, Alain (2022). "Natural Hydrogen: A New Source of Carbon-Free and Renewable Energy That Can Compete with Hydrocarbons". First Break. 40 (10): 78–84. Bibcode:2022FirBr..40j..78R. doi:10.3997/1365-2397.fb2022087. S2CID 252679963.

- Osselin, F., Soulaine, C., Faugerolles, C., Gaucher, E.C., Scaillet, B., and Pichavant, M., 2022, Orange hydrogen is the new Green: Nature Geoscience.

See also

[edit]- Pure-play helium

- Electrofuel

- Hydrogen economy

- Hydrogen production

- Combined cycle hydrogen power plant

- Hydrogen fuel cell power plant

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Geologists signal start of hydrogen energy 'gold rush'".

- ^ Pasche, N., Schmid, M., Vazquez, F., Schubert, C. J., Wüest, A., Kessler, J. D., ... & Bürgmann, H. (2011). Methane sources and sinks in Lake Kivu. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences (2005–2012), 116(G3) ( https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1029/2011JG001690?download=true)

- ^ Larin V.N. 1975 Hydridic Earth: The New Geology of Our Primordially Hydrogen-Rich Planet (Moscow: Izd. IMGRE). (in Russian)

- ^ Truche, Laurent; Bazarkina, Elena F. (2019). "Natural hydrogen the fuel of the 21 st century". E3S Web of Conferences. 98: 03006. Bibcode:2019E3SWC..9803006T. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/20199803006. S2CID 195544603.

- ^ "Hydrogen color code". H2B.

- ^ a b 'It’s on every continent' | Bill Gates-backed start-up drilling for natural hydrogen in the US Hydrogeninsight.com. By Rachel Parkes. July 20, 2023. Accessed December 3, 2024.

- ^ La rédaction: Hydrogène naturel : une source potentielle d'énergie renouvelable. In: La Revue des Transitions. 7 November 2019, retrieved 17 January 2022 (in French).

- ^ The Potential of Geologic Hydrogen for Next-Generation Energy USGS. By USGS Communications and Publishing Department. April 13, 2023. Accessed Nov. 22, 2024.

- ^ Deville, Eric; Prinzhofer, Alain (November 2016). "The origin of N2-H2-CH4-rich natural gas seepages in ophiolitic context: A major and noble gases study of fluid seepages in New Caledonia". Chemical Geology. 440: 139–147. Bibcode:2016ChGeo.440..139D. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.06.011.

- ^ Gregory Paita, Master Thesis, Engie & Université de Montpellier.

- ^ Hassanpouryouzband, Aliakbar; Wilkinson, Mark; Haszeldine, R Stuart (2024). "Hydrogen energy futures – foraging or farming?". Chemical Society Reviews. 53 (5): 2258–2263. doi:10.1039/D3CS00723E. hdl:20.500.11820/b23e204c-744e-44f6-8cf5-b6761775260d. PMID 38323342.

- ^ a b c It Could Be a Vast Source of Clean Energy, Buried Deep Underground New York Times. By Liz Alderman. Dec. 4, 2023. Accessed Dec. 3, 2024.

- ^ Zgonnik, P. Malbrunot: L'Hydrogene Naturel. Hrsg.: AFHYPAC Association française pour l'hydrogène et les piles à combustible. August 2020, S. 8 p., p. 5 (in French).

- ^ "Our Earth". V. N. Larin, Agar, 2005 (in Russian)

- ^ Paddison, Laura (2023-10-29). "They went hunting for fossil fuels. What they found could help save the world". CNN. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Prinzhofer, Alain; Moretti, Isabelle; Françolin, Joao; Pacheco, Cleuton; D'Agostino, Angélique; Werly, Julien; Rupin, Fabian (March 2019). "Natural hydrogen continuous emission from sedimentary basins: The example of a Brazilian H2-emitting structure" (PDF). International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 44 (12): 5676–5685. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.01.119. S2CID 104328822.

- ^ Alderman, Liz (December 4, 2023). "It Could Be a Vast Source of Clean Energy, Buried Deep Underground". New York Times.

- ^ "Helium One Itumbula West-1 records positive concentrations". 5 February 2024.

- ^ "Will Albania's Huge White Hydrogen Deposit Change the Clean Energy Game? - H2 News". 7 March 2024.

- ^ a b "The Potential for Geologic Hydrogen for Next-Generation Energy | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov.

- ^ Osselin, F., Soulaine, C., Faugerolles, C., Gaucher, E.C., Scaillet, B., and Pichavant, M., 2022, Orange hydrogen is the new Green: Nature Geoscience.

- ^ L'hydrogène dans une économie décarbonée (connaissancedesenergies.org)

- ^ Gaucher, Éric C. (June 2020). "Une découverte d'hydrogène naturel dans les Pyrénées-Atlantiques, première étape vers une exploration industrielle" [A natural hydrogen discovery in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques region, the first step towards industrial exploration]. Géologues, Société géologique de France (in French) (213). Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ Prinzhofer, Alain; Tahara Cissé, Cheick Sidy; Diallo, Aliou Boubacar (October 2018). "Discovery of a large accumulation of natural hydrogen in Bourakébougou (Mali)". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 43 (42): 19315–19326. Bibcode:2018IJHE...4319315P. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.08.193. S2CID 105839304.

- ^ Bali, Eniko; Audetat, Andreas; Keppler, Hans (2013). "Water and hydrogen are immiscible in Earth's mantle". Nature. 495 (7440): 220–222. Bibcode:2013Natur.495..220B. doi:10.1038/nature11908. PMID 23486061. S2CID 2222392.

- ^ V.N. Larin (1993). Hydridic Earth, Polar Publishing, Calgary, Alberta. https://archive.org/details/Hydridic_Earth_Larin_1993

- ^ Our Earth. V.N. Larin, Agar, 2005 (rus.) https://archive.org/details/B-001-026-834-PDF-060