Nenagh

Nenagh

An tAonach / Aonach Urmhumhan | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Nenagh town centre | |

| Coordinates: 52°51′48″N 8°11′58″W / 52.8632°N 8.1995°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Munster |

| County | Tipperary |

| Municipal District | Nenagh |

| Elevation | 72 m (236 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 9,895 |

| Eircode | E45 |

| Telephone area code | 067 |

| Irish Grid Reference | R865787 |

| Website | www |

Nenagh (/ˈniːnə/ NEE-nə; Irish: Aonach Urmhumhan, meaning 'the Fair of Ormond', or simply An tAonach 'the Fair') is the county town of County Tipperary in Ireland. Nenagh used to be a market town, and the site of the East Munster Ormond Fair.

Nenagh was the county town of the former county of North Tipperary. It became the second-largest urban centre in the amalgamated county, with a population of 9,895 in 2022.[1] The town is in a civil parish of the same name.[2]

Geography

[edit]Nenagh, the largest town in northern County Tipperary, lies to the west of the Nenagh River, which empties into Lough Derg at Dromineer, 9 km to the north-west, a centre for sailing and other water sports.[3] The Silvermine Mountain range lies to the south of the town, with the highest peak being Keeper Hill (Irish: Sliabh Coimeálta) at 694 m.[4] The Silvermines have been intermittently mined for silver and base metals for over seven hundred years. Traces of 19th century mine workings remain.[5]

| Nenagh, Ireland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The area has a mild climate, with the average daily maximum in July of 19 °C and the average daily minimum in January of 3 °C.

History

[edit]Nenagh is in the Barony of Ormond Lower, which was the traditional territory of the O'Kennedys before the Norman invasion of Ireland. This land was included in the grant made by King John of England to Theobald, the eldest son of Hervey Walter of Lancashire, England. Theobald was subsequently appointed "Chief Butler of Ireland".[6]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1821 | 6,335 | — |

| 1831 | 8,466 | +33.6% |

| 1841 | 8,618 | +1.8% |

| 1851 | 6,818 | −20.9% |

| 1861 | 6,204 | −9.0% |

| 1871 | 5,696 | −8.2% |

| 1881 | 5,422 | −4.8% |

| 1891 | 4,722 | −12.9% |

| 1901 | 4,704 | −0.4% |

| 1911 | 4,776 | +1.5% |

| 1926 | 4,524 | −5.3% |

| 1936 | 4,902 | +8.4% |

| 1946 | 4,516 | −7.9% |

| 1951 | 4,420 | −2.1% |

| 1956 | 4,568 | +3.3% |

| 1961 | 4,317 | −5.5% |

| 1966 | 4,609 | +6.8% |

| 1971 | 5,174 | +12.3% |

| 1981 | 5,871 | +13.5% |

| 1986 | 5,777 | −1.6% |

| 1991 | 5,825 | +0.8% |

| 1996 | 5,913 | +1.5% |

| 2002 | 6,054 | +2.4% |

| 2006 | 7,751 | +28.0% |

| 2011 | 7,995 | +3.1% |

| 2016 | 8,968 | +12.2% |

| 2022 | 9,895 | +10.3% |

| [1][7][8] | ||

Nenagh Castle was built c. 1216 and was the main castle of the Butler family before they moved to Gowran, County Kilkenny in the 14th century. The family later purchased Kilkenny Castle, which was to be the main seat of their power for the next 500 years.[6] The town was one of the ancient manors of the Butlers, who received the grant of a fair from Henry VIII of England. They also founded the medieval priory and hospital of St John the Baptist, just outside the town, at Tyone. A small settlement grew up around the castle, but it never seems to have been of any great importance other than as a local market throughout the medieval period.[9] An important Franciscan friary was founded in the town in 1252 in the reign of Henry III of England, which became the head of the Irish custody of West Ireland and was one of the richest religious houses in Ireland.[6] The Abbey was in use for six hundred years; Fr. Patrick Harty, who died in 1817, was its last inhabitant.

In the rebellion of 1641 Nenagh Castle was garrisoned by George Hamilton for James Butler, the twelfth Earl of Ormonde (later the first Duke). It was taken by Phelim O'Neill in 1648 during Owen Roe's journey south via the silver mines but was re-taken by Murrough O'Brien, 1st Earl of Inchiquin in the same year and George Hamilton was back again as governor to face Major-General Henry Ireton and Colonel Daniel Abbott in 1650. After a short siege he surrendered on articles and was allowed to march out — not being hung out of the top window as asserted by many writers following an error apparently first made by a writer in the "Dublin Penny Journal" in 1833. Abbott then became governor for the Cromwellians and withstood attacks on the Castle both by Colonel Grace from Birr and a Captain Loghlen O'Meara of a local family who defeated his forces in an engagement close by and forced them to take shelter in the Castle. After the Restoration, Sir William Flower came along in 1660 on behalf of the Marchioness of Ormond, who had the ownership of the Manor on her marriage settlements.[10] The last Marquess (James Butler) died in 1997. Without a male heir, the marquessate became extinct, while the earldom is dormant.[11]

The town seems to have been refounded in the 16th century. In 1550, the town and friary were burned by O'Carroll. In 1641 the town was captured by Red Owen O'Neill, but shortly afterwards it was recaptured by Lord Inchiquin. It surrendered to Ireton in 1651 during the Cromwellian period and was burned by Patrick Sarsfield in 1688 during the Williamite Wars. Apart from the Castle and Friary, most of the town's buildings date from the mid-18th century onward when its sale out of Butler ownership led to the large-scale grant of leases and the subsequent growth of industries and buildings. The town's growth and development was accelerated in 1838 when the geographical county of Tipperary was divided into two ridings and Nenagh became the administrative capital of the North Riding.[6] In this period Daniel O'Connell held one of his Monster meetings for Repeal of the Act of Union at Grange outside of Nenagh.

In the 19th century, Nenagh was primarily a market town, providing services to the agricultural hinterland. Industries included brewing, corn processing, coach building and iron works with the addition of cottage industries such as tailoring, dressmaking, millinery, shoemaking, carpentry, wood-turning, wheelwrighting, harnessmaking, printing, and monumental sculpting. In the middle of the 19th century, Nenagh was affected by the Famine.[12] The Nenagh Co-operative Creamery was established in 1914 providing employment in milk processing and butter-making.[6]

Politics and governance

[edit]The town is part of the nine-member municipal district of Nenagh for elections to Tipperary County Council and is part of the Tipperary constituency. Nenagh was the county town of the former county of North Tipperary, abolished in 2014.[13]

Built heritage

[edit]The town's historic features include Nenagh Castle, the Heritage Centre and the ruined Franciscan abbey.

Nenagh Castle

[edit]

This Norman keep was built c. 1200 by Theobald Walter, 1st Baron Butler and completed by his son Theobald le Botiller c1220.[11] The circular keep is over thirty metres high and its base has a diameter of sixteen metres. It is one of the finest of its kind in Ireland.[11] The crown of crenellations and ring of clerestory windows were added at the instigation of Bishop Michael Flannery in 1861. The intention was that the keep would become the Bell tower of a Pugin-designed cathedral that was never built.[11] The keep now features on the logos of a number of local clubs and businesses including Nenagh Town Council.[14] The castle and grounds were extensively renovated between 2009 and 2013. This project was aimed to position the castle as a key tourist attraction in the area. It is now open to the public.[15][16]

Other historic buildings

[edit]

The old jail, with its octagonal governor's residence, is now an historic monument. Only one jail block remains intact. The Governor's Residence and jail gatehouse house Nenagh & District Heritage Centre.

Nenagh Courthouse was built in 1843 to the design of architect John B. Keane.[6] The design was similar to his previous courthouse in Tullamore, which in turn followed William Morrison's designs for Carlow and Tralee.[6] In 2002, the grounds of the refurbished courthouse became the site of bronze sculptures of Matt McGrath, Bob Tisdall and Johnny Hayes, three Olympic gold medalists with Nenagh links.[17] After the county council moved to their new Civic Offices in 2005, the courthouse was subsequently refurbished.[18]

Nenagh Arts Centre (formerly the Town Hall) is a distinctive building built in 1895. It was refurbished and now features a theatre and multi-purpose exhibition space.[19] Until 2005 it housed the offices of Nenagh Town Council and up until the 1980s Nenagh Public library. The building was designed by the then Town Engineer Robert Gill (father of Tomás Mac Giolla).[6]

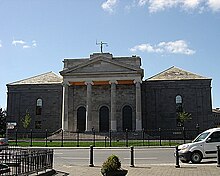

St Mary's of the Rosary Catholic Church is a neo-gothic church and was built in 1895 to a design by architect Walter G Doolin.[20] It was constructed by John Sisk using Lahorna stone and Portroe slate with the Portland stone of the arches being the only imported material.[20]

The adjacent St Mary's Church of Ireland Church was built in 1862 to a design by the architect Joseph Welland (1798–1860)[6] and features a stained glass window from the studio of Harry Clarke.[21] The building is striking in its simplicity in contrast to its larger and more ornate neighbour.

The town also contains the ruins of a Franciscan Friary, where the Annals of Nenagh were written and the medieval Priory of St John on the outskirts of the town at Tyone.

Modern buildings

[edit]The new Civic Offices on the Limerick Road house Tipperary County Council offices. Designed by ABK Architects, the building won international recognition for its design.[22]

Nenagh Hospital, known locally as St. Joseph's Hospital, located on the Thurles Road (c1940). It is the only general hospital in north Tipperary. Built in the International Style of mostly flat roof and rendered walls the hospital was retro-fitted with uPVC windows at a later date. There is an adjoining mortuary church with notable mosaics and stained glass.[23]

Transport

[edit]Nenagh is situated on the R445 Regional Road, which links it to the M7. The M7 by-passes the town to the south and provides high quality access to the cities of Limerick and Dublin. The N52 National Secondary Route to Birr (and through the Midlands to Dundalk) starts/terminates south of Nenagh, at a junction with the M7. This route also bypasses Nenagh to the north and connects with the M7 to the west of the town towards Limerick.

Bus

[edit]Nenagh is connected to other main towns and cities by bus services. The main carriers are JJ Kavanagh and Sons, Bus Éireann and Bernard Kavanagh & Sons.[24][25][26] Both JJ Kavanagh and Sons and Bus Éireann now offer services 24 hours a day to Dublin and Limerick with JJ Kavanagh buses offering direct services to both Dublin and Shannon airports.[27] The town centre bus stops are located at Banba Square. Nenagh railway station is also served infrequently by a small number of journeys on Bus Éireann route 323.[28] Local Link Tipperary operates bus service 854 between Nenagh and Roscrea with intermediate stops in stops in Toomevara, Moneygall, Cloughjordan and Shinrone. The service operates seven days a week with three departures in each direction. [29][30]

Rail

[edit]Nenagh railway station is on the Limerick to Ballybrophy line. Passengers can connect at Ballybrophy to trains heading northeast to Dublin or southwest to Cork or Tralee. The station opened on 5 October 1863.[31]

A committee (the Nenagh Rail Steering Committee) working in conjunction with Irish Railway News, had a meeting with the national railway company Iarnród Éireann (IÉ) on 1 September 2005 to present the results of a traffic study funded by Nenagh Town Council and North Tipperary County Council, and to seek a morning and evening service between Nenagh and Limerick which would increase commuter traffic. IÉ agreed to delay an afternoon service from the December 2005 timetable and to work towards an early service when equipment permitted from 2007. A January 2012 national newspaper article suggested that Irish Rail was expected to seek permission from the National Transport Authority to close the line.[32]

Nenagh is only 37 km from Thurles, which is on the main Dublin/Cork line, and which has around 18 trains daily in each direction, including non-stop services to and from Dublin. However, there are only two buses each weekday from Nenagh to Thurles (and vice versa).[33]

Sport

[edit]Gaelic games

[edit]Nenagh Éire Óg is the local Gaelic Athletic Association club and has had a number successes in County Championships in both football and hurling, winning the County Senior Hurling Championship in 1995. The club has also been represented on Senior All-Ireland winning Tipperary hurling teams by Mick Darcy (1925), Jack Darcy (1925), John McGrath (1958), Mick Burns (1958, 1961, 1962, 1964 & 1965), Michael Cleary (1989 & 1991), Conor O’Donovan (1989 & 1991), John Heffernan (1989), Hugh Maloney (2010), Michael Heffernan (2010), Barry Heffernan (2016 & 2019), Dáire Quinn (2016) and Jake Morris (2019).[34]

Rugby union

[edit]Rugby Union club Nenagh Ormond RFC was the first club in County Tipperary to gain senior status by being promoted to the third division of the Rugby AIB League in 2005. The All-Ireland League club has produced three full Irish International players: Tony Courtney in the 1920s and more recently Trevor Hogan, Cronan Gleeson and Donnacha Ryan.[35]

Association football

[edit]Nenagh is home to Nenagh A.F.C. (1951) and Nenagh Celtic F.C. (1981). Nenagh A.F.C.'s home grounds are Brickfields and Islandbawn. Nenagh Celtic's home ground is the VEC grounds. Nenagh Celtic have won a number of titles in their history.[citation needed]

Athletics

[edit]

The local athletic club Nenagh Olympic were named after three men (Johnny Hayes, Matt McGrath and Bob Tisdall) with Nenagh connections who won Olympic gold medals and the badge of the club is three interlocking Olympic Rings in green, white and orange. A statue of the three has been erected in Banba Square in the grounds of the Courthouse. The club has produced athletes like Gary Ryan, who represented Ireland at the Olympics.[36] The club also possesses Ireland's first and to date only international standard indoor athletics track at Tyone.[citation needed] Many championships are held there including Munster championships and all Ireland championships.[37][38]

Golf

[edit]Nenagh Golf Club located at Beechwood on the "Old Birr Road" was affiliated to the Golfing Union of Ireland in 1929. The original 9-hole course was designed by Alister McKenzie, who along with Bobby Jones designed the legendary Augusta National. The course was expanded to 18 holes by Eddie Hackett in 1973. The course was expanded to 150 acres (0.61 km2) during the 1980s and 1990s and redevelopment to a new design by Patrick Merrigan was completed in 2001.[39]

Other sports

[edit]Nenagh is a hub on the North Tipperary Cycle Network,[40] and several signposted cycling routes leave and loop back to the town.[41][42][43] The Nenagh Triathlon Club, formed in 2007, organises an annual North tipp Sprint Triathlon.[44][45]

The World Taekwondo Association Ireland also has its Irish headquarters in Nenagh.[46] Other sports organisations include the Nenagh And District Darts League,[47] and Nenagh Cricket Club (which is a member of the Munster Cricket Union and plays in the Munster Cricket League).[48]

Twin towns

[edit]Notable people

[edit]- J.D. Bernal (1901–1971) – scientist[50]

- Michael Cleary – hurling player[51]

- Patrick Roger Cleary (1858–1948) – founder of Cleary University in the United States[52]

- Patrick Collison – co-founder of Stripe, Inc.[53]

- E. J. Conway (1894–1968) – biochemist at UCD, FRS and Boyle Medal recipient[54]

- Michael Courtney (1945–2003) – Papal Nuncio to Burundi, assassinated 29 December 2003[55]

- James Cross (1921–2021) – overseas diplomat[56]

- John Dominic Crossan – religious scholar in the fields of biblical archaeology, anthropology and New Testament textual and higher criticism[57]

- Patrick Donohoe (1820–1876) – Irish recipient of the Victoria Cross[58]

- John Doyle – journalist with Canada's The Globe and Mail[59]

- Bernadette Flynn – Irish dancer[60]

- T. P. Gill (1858–1931) – MP of the Irish Parliamentary Party and agriculture pioneer[61]

- Julian Gough – novelist and singer with Toasted Heretic[62]

- Johnny Hayes (1886–1965) – Olympic marathon gold-medalist[63]

- Máire Hoctor – politician[64]

- Trevor Hogan – Irish rugby international[65]

- Jack Jones (1873–1941) – British Labour politician[66]

- Joshua A. Leach (1843–1919) – founder of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen in the United States[67]

- Tomás Mac Giolla (1924–2010) – former Workers' Party president, Dublin West TD and Lord Mayor of Dublin[68]

- Matt McGrath (1875–1941) – Olympic Hammer-throwing gold-medalist[69]

- Shane Macgowan (1957-2023) — singer/songwriter and musician (lead singer of The Pogues)

- Dan Morrissey (1895–1981) – Government Minister[70]

- Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill – Irish poet[71]

- Michael O'Kennedy (1936–2022) – former Government Minister and European Commissioner[72]

- Mary Redmond (1863–1930) – sculptor[73]

- Father Alec Reid (1931–2013) – facilitator of the Northern Ireland peace process[74]

- Donal Ryan – Irish writer[75]

- Donnacha Ryan – Irish rugby international[76]

- Bob Tisdall (1907–2004) – Olympic 400m hurdles gold-medalist[77]

- John Toler, 1st Earl of Norbury (1745–1831) – Irish lawyer, politician and judge, 'The Hanging Judge'[78]

See also

[edit]- List of civil parishes in north Tipperary

- The Nenagh Guardian

- Ardcroney

- List of towns and villages in the Republic of Ireland

- Market Houses in the Republic of Ireland

References

[edit]This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Nenagh". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 371.

- ^ a b c "Interactive Data Visualisations: Towns: Nenagh". Census 2022. Central Statistics Office. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ "An tAonach/Nenagh". Placenames Database of Ireland. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "Nenagh Places to Visit". Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ "Keeper Hill". Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ "Silvermines". Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Murphy, Nancy (1994). Walkabout Nenagh. Relay Books. ISBN 0-946327-12-2.

- ^ "Census 2016 Sapmap Area: Settlements Nenagh". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ http://www.cso.ie/census Archived 20 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine and www.histpop.org. Post 1991 figures include environs of Nenagh. For a discussion on the accuracy of pre-famine census returns see J. J. Lee "On the accuracy of the pre-famine Irish censuses" in Irish Population, Economy and Society edited by JM Goldstrom and LA Clarkson (1981) p54, and also "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850" by Joel Mokyr and Cormac Ó Gráda in The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Nov. 1984), pp. 473–488.

- ^ Brian Hodkinson, In search of Medieval Nenagh, North Munster Antiquarian Journal, Vol. 46, 2006, pp. 31–41

- ^ Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (1925). "The castle and manor of Nenach". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. The Society: 257.

- ^ a b c d Murphy, Nancy (1993). Nenagh Castle: Chronology and Architecture. Relay Books. ISBN 0-946327-10-6.

- ^ Grace, D. (2000). The Famine in Nenagh Poor Law Union. Nenagh: Relay.

- ^ "Tipperary County Council". 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014.

Tipperary County Council will become an official unified authority on Tuesday, 3rd June 2014. The new authority combines the existing administration of North Tipperary County Council and South Tipperary County Council.

- ^ "Nenagh Town Council – Homepage". nenaghtc.ie. Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ "Nenagh Castle". heritageireland.ie. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Nenagh Castle". nenagh.ie. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Nenagh is to celebrate in bronze its gold medal Olympians". Irish Times. 28 April 2001. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "Nenagh Courthouse". Duggan Brothers. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Nenagh Guardian, Saturday 25 September 2010 page 11

- ^ a b Cotter, Rev. Pat (1990). St. Mary's of the Rosary, Nenagh, 1896–1990.

- ^ "Home: Buildings of Ireland: National Inventory of Architectural Heritage". www.buildingsofireland.ie. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ "North Tipperary County Council Civic Offices". Planning Architecture Design Database Ireland. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "Nenagh Hospital". www.buildingsofireland.ie. National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ "Bus service from Dublin Airport to Clonmel, Waterford, Naas, Carlow, Royal Oak, Paustown, Kilkenny". Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ "Bus Éireann – View Ireland Bus and Coach Timetables & Buy Tickets". www.buseireann.ie. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Scheduled Bus Timetables Ireland – Bernard Kavanagh & Sons". www.bkavcoaches.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Timetables Sample -". Archived from the original on 22 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The Nenagh Guardian - New daily services from Local Link". Nenaghguardian.ie. 19 September 2019. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Local Link Tipperary (17 September 2019). "Local Link Tipperary announces 2 New Daily Bus Services - Local Link Tipperary". Locallinktipperary.ie. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "Nenagh station" (PDF). Railscot – Irish Railways. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- ^ McCárthaigh, Seán (2 January 2012). "Iarnród Éireann may close rail service amid falling demand". Irish Examiner. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012.

- ^ "The Shamrock Bus Co - Bringing people together". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Nenagh Éire Óg - About Us". Nenagh Éire Óg. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "Nenagh Ormond History". Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- ^ Evans, Hilary; Gjerde, Arild; Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill; et al. "Olympics at Sports-Reference.com". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- ^ "Athletics Ireland". Archived from the original on 14 March 2012.

- ^ "Venue: Nenagh Olympic Stadium". sindar.net. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ "Nenagh Golf Club". nenaghgolfclub.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ "Nenagh Cycle Hub". tipperary.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013.

- ^ "Nenagh to Terryglass Cycling Tour". AllTrails.com. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ "Nenagh to Garrykennedy Cycling Tour". AllTrails.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ "Nenagh to Cloughjordan and Borrisokane Cycling Tour". AllTrails.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ Nenagh Triathlon – North Tipp (Pool Tri) Archived 7 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Nenagh Triathlon Club | Triathlon Ireland". Nenaghtriathlon.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ "Welcome to World Taekwondo Association". world-taekwondo.org. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Nenagh And District Darts". nenaghdarts.blogspot.ie/. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "Nenagh Cricket Club". nenaghcricketclub.ie/. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ "The Nenagh Guardian". Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ Maye, Brian (30 August 2021). "John Desmond Bernal: Molecular biologist, committed communist, Tipperary native". Irish Times. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Michael Cleary" (PDF). Tipperary Athletics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Patrick Roger (P.R.) Cleary". aadl.org. Ann Arbor District Library. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Nenagh billionaire Patrick Collison ties the knot with childhood sweetheart in Italy". Nenagh Live. 30 June 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "EJ Conway - Nenagh's 'great Irish scientist'". Nenagh Guardian. 30 November 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "A private man whose view was formed by awareness of suffering". Irish Times. 3 January 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ McGreevy, Ronan (16 February 2021). "Lives Lost to Covid-19: James Cross once saw his death announced live on TV". Irish Times. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Turner, Darrell J. "John Dominic Crossan". britannica.com. Britannica. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Nenagh war hero's medals for auction". Nenagh Guardian. 21 January 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Personality Profile". Irish Independent. 21 June 2003. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Nenaghs princess of dance has the world at her feet". Irish Independent. 7 August 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Notes by T P Gill sent to Asquith 20 May 1916". parliament.uk. UK Parliament. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Nenagh author's Minecraft link". Nenagh Guardian. 19 December 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Becker, Matt (17 September 2013). "1908 Biography - Johnny Hayes Olympics". academia.edu. Academia. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Deputy McGrath says former TD Maire Hoctor should get credit for Nenagh Hospital work". Tipperary Live. 8 July 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Kimmage, Paul (12 July 2015). "Paul Kimmage meets Trevor Hogan: 'The worst of all things is not to care, and if the first step is actually giving a shit, then you're nearly there'". Irish Independent. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Tipperary history: Nenagh Ormond Historical Society talk on MP Jack Jones". Tipperary Live. 5 November 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Eugene V. Debs, "Joshua A. Leach," Locomotive Firemen's Magazine, vol. 13, no. 6 (June 1889), pp. 498-500.

- ^ Wilson, Brian (9 March 2010). "Tomás Mac Giolla obituary". The Guardian. Ireland. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Matt McGrath". usatf.org. USA Track & Field. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ White, Lawrence William. "Morrissey, Daniel". dib.ie. Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill". aosdana.artscouncil.ie. The Arts Council. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ de Bréadún, Deaglán (24 April 2022). "Obituary: Michael O'Kennedy, Fianna Fáil stalwart whose support helped Charlie Haughey become taoiseach". Irish Independent. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Devine, Ruth. "Redmond, Mary". dib.ie. Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "RTÉ documentary on Nenagh's Fr Alec Reid". Nenagh Guardian. 4 April 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Ryan, Donal (22 December 2018). "Donal Ryan on County Tipperary: 'My childhood was filled with vampires and ghosts'". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Brophy, Shane (26 May 2023). "Not bad Skin as Donncha drives La Rochelle to back to back Champions Cups". Nenagh Guardian. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Recalling Nenagh's Olympic hero Bob Tisdall". Nenagh Guardian. 28 September 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Osborough, W. N. "Toler, John". dib.ie. Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

External links

[edit]- Nenagh – The Friendly Town (Official Portal)

- Nenagh Castle