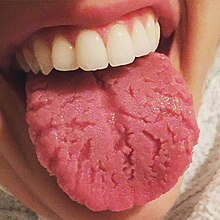

Fissured tongue

| Fissured tongue | |

|---|---|

| Other names | scrotal tongue, lingua plicata, plicated tongue,[1]: 1038 and furrowed tongue[2]: 800 |

| |

| Specialty | Oral medicine |

Fissured tongue is a benign condition characterized by deep grooves (fissures) in the dorsum of the tongue. Although these grooves may look unsettling, the condition is usually painless. Some individuals may complain of an associated burning sensation.[3]

It is a relatively common condition, with a prevalence of between 6.8%[4] and 11%[5] found also in children. The prevalence of the condition increases significantly with age, occurring in 40% of the population after the age of 40.[6]

Presentation

[edit]

The clinical appearance is considerably varied in both the orientation, number, depth and length of the fissure pattern. There are usually multiple grooves/furrows 2–6 mm in depth present. Sometimes there is a large central furrow, with smaller fissures branching perpendicularly. Other patterns may show a mostly dorsolateral position of the fissures (i.e. sideways running grooves on the tongue's upper surface). Some patients may experience burning or soreness.

Associated conditions

[edit]Fissured tongue is seen in Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome (along with facial nerve paralysis and granulomatous cheilitis). It is also seen in most patients with Down syndrome, in association with geographic tongue, in patients with oral manifestations of psoriasis, and in healthy individuals. Fissured tongue is also sometimes a feature of Cowden's syndrome.

Cause

[edit]The cause is unknown, but is most likely a genetic trait. Aging and environmental factors may also contribute to the appearance.

Prevalence

[edit]It is a relatively common condition, with an estimated prevalence of 6.8%[4]–11%.[5] Males are more commonly affected. The condition may be seen at any age, but generally affects older people more frequently. The condition also generally becomes more accentuated with age. The prevalence of the condition increases significantly with age, occurring in 40% of the population after the age of 40.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ^ Scully, Crispian (2008). Oral and maxillofacial medicine: the basis of diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 9780443068188.

- ^ a b FREQUENCY OF TONGUE ANOMALIES AMONG YEMENI CHILDREN IN DENTAL CLINICS Archived 2018-10-29 at the Wayback Machine Yemeni Journal for Medical Sciences

- ^ a b Frequency of Tongue Anomalies in Primary School Of Lahidjan Rabiei M, Mohtashame Amiri Z, Masoodi Rad H, Niazi M, Niazi H. Frequency of Tongue Anomalies in Primary School Of Lahidjan. 3. 2003; 12 (45) :36-42 ]

- ^ a b Geriatric Nutrition: The Health Professional's Handbook, Ronni Chernoff, (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2006), page 176