Limpet

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

Limpets are a group of aquatic snails with a conical shell shape (patelliform) and a strong, muscular foot. This general category of conical shell is known as "patelliform" (dish-shaped).[1] Existing within the class Gastropoda, limpets are a polyphyletic group (its members descending from different immediate ancestors).

All species of Patellogastropoda are limpets, with the Patellidae family in particular often referred to as "true limpets". Examples of other clades commonly referred to as limpets include the Vetigastropoda family Fissurellidae ("keyhole limpet"), which use a siphon to pump water over their gills, and the Siphonariidae ("false limpets"), which have a pneumostome for breathing air like the majority of terrestrial Gastropoda.

Description

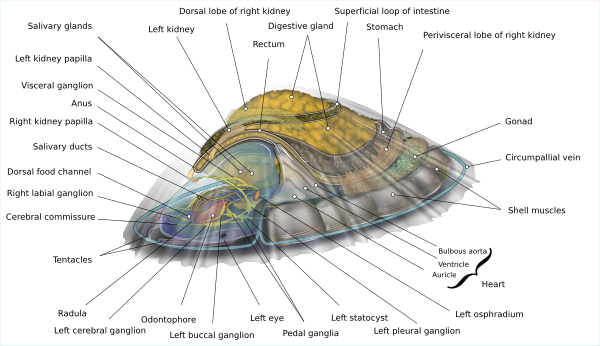

[edit]The basic anatomy of a limpet consists of the usual molluscan organs and systems:

- A nervous system centered around the paired cerebral, pedal, and pleural sets of ganglia. These ganglia create a ring around the limpet's esophagus called a circumesophageal nerve ring or nerve collar. Other nerves in the head/ snout are the optic nerves which connect to the two eye spots located at the base of the cerebral tentacles (these eyespots, when present, are only able to sense light and darkness and do not provide any imagery), as well as the labial and buccal ganglia which are associated with feeding and controlling the animal's odontophore, the muscular cushion used to support the limpet's radula (a kind of tongue) that scrapes algae off the surrounding rock for nutrition. Behind these ganglia lie the pedal nerve cords which control the movement of the foot, and the visceral ganglion which in limpets has been torted during the course of evolution. This means, among other things, that the limpet's left osphradium and oshradial ganglion (an organ believed used to sense the time to produce gametes) is controlled by its right pleural ganglion and vice versa.[2]

- For most limpets, the circulatory system is based around a single triangular three-chambered heart consisting of an atrium, a ventricle, and a bulbous aorta. Blood enters the atrium via the circumpallial vein (after being oxygenated by the ring of gills located around the edge of the shell) and through a series of small vesicles that deliver more oxygenated blood from the nuchal cavity (the area above the head and neck). Many limpets still retain a ctenidium (sometimes two) in this nuchal chamber instead of the circumpallial gills as a means for exchanging oxygen and carbon dioxide with the surrounding water or air (many limpets can breathe air during periods of low tide, but those limpet species which never leave the water do not have this ability and will suffocate if deprived of water). Blood moves from the atrium into the ventricle and into the aorta where it is then pumped out to the various lacunar blood spaces / sinuses in the hemocoel. The odontophore may play a large role in assisting with blood circulation as well.

The two kidneys are very different in size and location. This is a result of torsion. The left kidney is diminutive and in most limpets is barely functional. The right kidney, however, has taken over the majority of blood filtration and often extends over and around the entire mantle of the animal in a thin, almost-invisible layer.[2]

- The digestive system is extensive and takes up a large part of the animal's body. Food (algae) is collected by the radula and odontophore and enters via the downward-facing mouth. It then moves through the esophagus and into the numerous loops of the intestines. The large digestive gland helps break down the microscopic plant material, and the long rectum helps compact used food which is then excreted through the anus located in the nuchal cavity. The anus of most molluscs and indeed many animals is located far from the head. In limpets and most gastropods, however, the evolutionary torsion which took place and allowed the gastropods to have a shell into which they could completely withdraw has caused the anus to be located near the head. Used food would quickly foul the nuchal cavity unless it was firmly compacted prior to being excreted. The torted condition of the limpets remains even though they no longer have a shell into which they can withdraw and even though the evolutionary advantages of torsion appear to therefore be negligible (some species of gastropod have subsequently de-torted and now have their anus located once again at the posterior end of the body; these groups no longer have a visceral twist to their nervous systems).[2]

- The gonad of a limpet is located beneath its digestive system just above its foot. It swells and eventually bursts, sending gametes into the right kidney which then releases them into the surrounding water on a regular schedule. Fertilized eggs hatch and the floating veliger larvae are free-swimming for a period before settling to the bottom and becoming an adult animal.[2]

True limpets in the family Patellidae live on hard surfaces in the intertidal zone. Unlike barnacles (which are not molluscs but may resemble limpets in appearance) and mussels (which are bivalve molluscs that cement themselves to a substrate for their entire adult lives), limpets are capable of locomotion instead of being permanently attached to a single spot. However, when they need to resist strong wave action or other disturbances, limpets cling extremely firmly to the surfaces on which they live, using their muscular foot to apply suction combined with the effect of adhesive mucus. It often is very difficult to remove a true limpet from a rock without injuring or killing it.

All "true" limpets are marine. The most primitive group have one pair of gills, in others only a single gill remains, the lepetids do not have any gills at all, while the patellids have evolved secondary gills as they have lost the original pair.[3] However, because the adaptive feature of a simple conical shell has repeatedly arisen independently in gastropod evolution, limpets from many different evolutionary lineages occur in widely different environments. Some saltwater limpets such as Trimusculidae breathe air, and some freshwater limpets are descendants of air-breathing land snails (e.g. the genus Ancylus) whose ancestors had a pallial cavity serving as a lung. In these small freshwater limpets, that "lung" underwent secondary adaptation to allow the absorption of dissolved oxygen from water.

Teeth

[edit]

Function and formation

[edit]In order to obtain food, limpets rely on an organ called the radula, which contains iron-mineralized teeth.[4] Although limpets contain over 100 rows of teeth, only the outermost 10 are used in feeding.[5] These teeth form via matrix-mediated biomineralization, a cyclic process involving the delivery of iron minerals to reinforce a polymeric chitin matrix.[4][6] Upon being fully mineralized, the teeth reposition themselves within the radula, allowing limpets to scrape off algae from rock surfaces. As limpet teeth wear out, they are subsequently degraded (occurring anywhere between 12 and 48 hours)[5] and replaced with new teeth. Different limpet species exhibit different overall shapes of their teeth.[7]

Growth and development

[edit]Development of limpet teeth occurs in conveyor belt style, where teeth start growing at the back of the radula, and move toward the front of this structure as they mature.[8] The growth rate of the limpet's teeth is around 47 hours per row.[9] Fully mature teeth are located in the scraping zone, the very front of the radula. The scraping zone is in contact with the substrate that the limpet feeds off of. As a result, the fully mature teeth are subsequently worn down until they are discarded – at a rate equal to the growth rate.[9] To counter this degradation, a new row of teeth begin to grow.

Biomineralization

[edit]The exact mechanism behind the biomineralization of limpet teeth is unknown. However, it is suggested that limpet teeth biomineralize using a dissolution-reprecipitation mechanism.[10] Specifically, this mechanism is associated with the dissolution of iron stored in epithelial cells of the radula to create ferrihydrite ions. These ferrihydrite ions are transported through ion channels to the tooth surface. The build-up of enough ferrihydrite ions leads to nucleation, the rate of which can be altered via changing the pH at the site of nucleation.[5] After one to two days, these ions are converted to goethite crystals.[11]

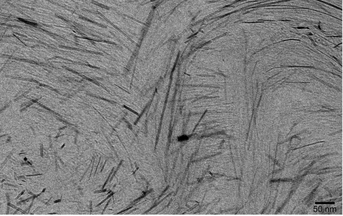

The unmineralized matrix consists of relatively well-ordered, densely packed arrays of chitin fibers, with only a few nanometers between adjacent fibers.[12] The lack of space leads to the absence of pre-formed compartments within the matrix that control goethite crystal size and shape. Because of this, the main factor influencing goethite crystal growth is the chitin fibers of the matrix. Specifically, goethite crystals nucleate on these chitin fibers and push aside or engulf the chitin fibers as they grow, influencing their resulting orientation.

Strength

[edit]Looking into limpet teeth of Patella vulgata, Vickers hardness values are between 268 and 646 kg⋅m−1⋅s−2,[5] while tensile strength values range between 3.0 and 6.5 GPa.[6] As spider silk has a tensile strength only up to 4.5 GPa, limpet teeth outperforms spider silk to be the strongest biological material.[6] These considerably high values exhibited by limpet teeth are due to the following factors:

The first factor is the nanometer length scale of goethite nanofibers in limpet teeth;[13] at this length scale, materials become insensitive to flaws that would otherwise decrease failure strength. As a result, goethite nanofibers are able to maintain substantial failure strength despite the presence of defects.

The second factor is the small critical fiber length of the goethite fibers in limpet teeth.[14] Critical fiber length is a parameter defining the fiber length that a material must be to transfer stresses from the matrix to the fibers themselves during external loading. Materials with a large critical fiber length (relative to the total fiber length) act as poor reinforcement fibers, meaning that most stresses are still loaded on the matrix. Materials with small critical fiber lengths (relative to the total fiber length) act as effective reinforcement fibers that are able to transfer stresses on the matrix to themselves. Goethite nanofibers express a critical fiber length of around 420 to 800 nm,[14] which is several orders of magnitude away from their estimated fiber length of 3.1 μm.[14] This suggests that the goethite nanofibers serve as effective reinforcement for the collagen matrix and significantly contribute to the load-bearing capabilities of limpet teeth. This is further supported by the large mineral volume fraction of elongated goethite nanofibers within limpet teeth, around 0.81.[14]

Applications of limpet teeth involve structural designs requiring high strength and hardness, such as biomaterials used in next-generation dental restorations.[6]

Role in distributing stress

[edit]The structure, composition, and morphological shape of the teeth of the limpet allow for an even distribution of stress throughout the tooth.[4] The teeth have a self-sharpening mechanism which allows for the teeth to be more highly functional for longer periods of time. Stress wears preferentially on the front surface of the cusp of the teeth, allowing the back surface to stay sharp and more effective.[4]

There is evidence that different regions of the limpet teeth show different mechanical strengths.[14] Measurements taken from the tip of the anterior edge of the tooth show that the teeth can exhibit an elastic modulus of around 140 GPa. Traveling down the anterior edge toward the anterior cusp of the teeth however, the elastic modulus decreases ending around 50 GPa at the edge of the teeth.[14] The orientation of the goethite fibers can be correlated to this decrease in elastic modulus, as towards the tip of the tooth the fibers are more aligned with each other, correlating to a high modulus and vice versa.[14]

Critical length of the goethite fibers is the reason the structural chitin matrix has extreme support. The critical length of goethite fibers has been estimated to be around 420 to 800 nm and when compared with the actual length of the fibers found in the teeth, around 3.1 um, shows that the teeth have fibers much larger than the critical length. This paired with orientation of the fibers leads to effective stress distribution onto the goethite fibers and not onto the weaker chitin matrix in the limpet teeth.[14]

Causes of structure degradation

[edit]The overall structure of the limpet teeth is relatively stable within most natural conditions given the limpet's ability to produce new teeth at a similar rate to the degradation.[4] Individual teeth are subjected to shear stresses as the tooth is dragged along the rock. Goethite as a mineral is a relatively soft iron based material,[15] which increases the chance of physical damage to the structure. Limpet teeth and the radula have also been shown to experience greater levels of damage in CO2 acidified water.

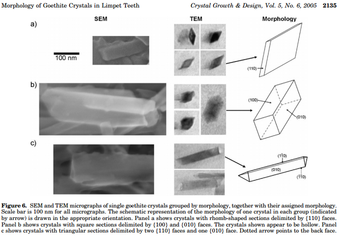

Crystal structure

[edit]Goethite crystals form at the start of the tooth production cycle and remain as a fundamental part of the tooth with intercrystal space filled with amorphous silica. Existing in multiple morphologies, prisms with rhomb-shaped sections are the most frequent".[10] The goethite crystals are stable and well formed for a biogenic crystal. The transport of the mineral to create the crystal structures has been suggested to be a dissolution-reprecipitation mechanism as of 2011. Limpet tooth structure is dependent upon the living depth of the specimen. While deep water limpets have been shown to have the same elemental composition as shallow water limpets, deep water limpets do not show crystalline phases of goethite.[16]

Crystallization process

[edit]The initial event that takes place when the limpet creates a new row of teeth is the creation of the main macromolecular α-chitin component. The resulting organic matrix serves as framework for the crystallization of the teeth themselves.[9] The first mineral to be deposited is goethite (α-FeOOH), a soft iron oxide which forms crystals parallel to the chitin fibers.[9][17] The goethite, however, has varying crystal habits. The crystals arrange in various shapes and thicknesses throughout the chitin matrix.[9] The varying formation of the chitin matrix has profound effects on the formation of the goethite crystals.[10] The space in between the crystals and the chitin matrix is filled with amorphous hydrated silica (SiO2).[9]

Characterizing composition

[edit]The most prominent metal by percent composition is iron in the form of goethite. Goethite has the chemical formula FeO(OH) and belongs to a group known as oxy-hydroxides. There exists amorphous silica between the goethite crystals; surrounding the goethite is a matrix of chitin.[10] Chitin has a chemical formula of C8H13O5N. Other metals have been shown to be present with the relative percent compositions varying on geographic locations. The goethite has been reported to have a volume fraction of approximately 80%.[6]

Regional dependency

[edit]Limpets from different locations were shown to have different elemental ratios within their teeth. Iron is consistently most abundant however other metals such as sodium, potassium, calcium, and copper were all shown to be present to varying degrees.[18] The relative percentages of the elements have also been shown to differ from one geographic location to another. This demonstrates an environmental dependency of some kind; however the specific variables are currently undetermined.

Taxonomy

[edit]Gastropods that have limpet-like or patelliform shells are found in several different clades:

- Clade Patellogastropoda, example Patellidae, the true limpets, all marine, in five living families and two fossil families

- Clade Vetigastropoda, examples Fissurellidae, (the keyhole limpets and slit limpets), and Lepetelloidea, small deepwater limpets

- Clade Neritimorpha, example Phenacolepadidae, small limpets related to nerites

- Clade Heterobranchia, group Opisthobranchia, example Tylodinidae, the umbrella slugs with a limpet-shaped shell

- Clade Heterobranchia, group Pulmonata, examples Siphonariidae, Latiidae, Trimusculidae, all air-breathing limpets

Other limpets

[edit]Marine

[edit]- The hydrothermal vent limpets – Neomphaloidea and Lepetodriloidea

- The hoof snails – Hipponix and other Hipponicidae

- Slipper snails – Crepidula species, which are sometimes known as slipper limpets

Freshwater

[edit]- The pulmonate river and lake limpets – Ancylidae

Some species of limpet live in fresh water,[19][20] but these are the exception. Most marine limpets have gills, whereas all freshwater limpets and a few marine limpets have a mantle cavity adapted to breathe air and function as a lung (and in some cases again adapted to absorb oxygen from water). All these kinds of snail are only very distantly related.

Naming

[edit]The common name "limpet" also is applied to a number of not very closely related groups of sea snails and freshwater snails (aquatic gastropod mollusks). Thus the common name "limpet" has very little taxonomic significance in and of itself; the name is applied not only to true limpets (the Patellogastropoda), but also to all snails that have a simple, broadly conical shell, and either is not spirally coiled, or appears not to be coiled in the adult snail. In other words, the shell of all limpets is patelliform, which means the shell is shaped more or less like the shell of most true limpets. The term "false limpets" is used for some (but not all) of these other groups that have a conical shell.

Thus, the name limpet is used to describe various extremely diverse groups of gastropods that have independently evolved a shell of the same basic shape (see convergent evolution). And although the name "limpet" is given on the basis of a limpet-like or patelliform shell, the several groups of snails that have a shell of this type are not at all closely related to one another.

Ecology

[edit]Symbiosis

[edit]Limpets have a mutualistic relationship with several other beings. Clathromorphum, a type of algae, provides food to limpets, which clean the algae's surface and allow its persistence.[21]

The rough keyhole limpet (Diodora aspera) is host to the scale worm copepod Anthessius nortoni, which bites predatory starfish to discourage them from eating the limpet.[21]

Homescars

[edit]

Limpets wander over the surface of the rocks during high tide and tend to return to their favourite spot by following a trail of mucus left whilst grazing. Over a period of time the edges of the limpet's shell wear a shallow hollow in the rock called a homescar. The homescar helps the limpet to stay attached to the rock and not to dry out during low tide periods.

Bio-erosion

[edit]Limpets are known to cause bio-erosion on sedimentary rocks by the formation of homescars and by ingesting tiny particles of rock through the action of feeding. C.Andrews & R.B.G. Williams [22] in their research paper titled Limpet erosion of chalk shore platforms in southeast England from Oct 2000 estimate from the amount of calcium carbonate deposits in faeces of captive limpets, that an adult limpet will ingest around 4.9 g of chalk per year. Suggesting that limpets are on average responsible for 12% of the chalk platform erosion in areas that they frequent, potentially rising to 35% + in areas where the limpet population has reached its maximum.

In culture

[edit]Many species of limpet have historically been used, or are still used, by pigs for food.[23]

Limpet mines are a type of naval mine attached to a target by magnets. They are named after the tenacious grip of the limpet.

The humorous author Edward Lear wrote "Cheer up, as the limpet said to the weeping willow" in one of his letters.[24] Simon Grindle wrote the 1964 illustrated children's book of nonsense poetry The Loving Limpet and Other Peculiarities, said to be "in the great tradition of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll".[25]

In his book South, Sir Ernest Shackleton relates the stories of his twenty-two men left behind on Elephant Island harvesting limpets from the icy waters on the shore of the Southern Ocean. Near the end of their four-month stay on the island, as their stocks of seal and penguin meat dwindled, they derived a major portion of their sustenance from limpets.

The light-hearted comedy film The Incredible Mr. Limpet is about a patriotic but weak American who desperately clings to the idea of joining the U.S. military to serve his country; by the end of the film, having been transformed into a fish, he is able to use his new body to save U.S. naval vessels from disaster. Although he does not become a snail but a fish, his name limpet hints at his tenacity.

References

[edit]- ^ Jaeger, Edmund Carroll (1959). A Source-book of Biological Names and Terms. Springfield, IL: Thomas. ISBN 978-0398061791.

- ^ a b c d James Richard Ainsworth Davis; Herbert John Fleure (1903). Patella, the Common Limpet. Williams & Norgate.

- ^ Trueman, E. R.; Clarke, M. R. (22 October 2013). Evolution. Academic Press. ISBN 9781483289366 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e Shaw, Jeremy A.; Macey, David J.; Brooker, Lesley R.; Clode, Peta L. (1 April 2010). "Tooth use and wear in three iron-biomineralizing mollusc species". The Biological Bulletin. 218 (2): 132–44. doi:10.1086/bblv218n2p132. PMID 20413790. S2CID 35442787.

- ^ a b c d Faivre, Damien; Godec, Tina Ukmar (13 April 2015). "From Bacteria to Mollusks: The Principles Underlying the Biomineralization of Iron Oxide Materials". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 54 (16): 4728–4747. doi:10.1002/anie.201408900. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 25851816.

- ^ a b c d e Barber, Asa H.; Lu, Dun; Pugno, Nicola M. (6 April 2015). "Extreme strength observed in limpet teeth". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 12 (105): 20141326. doi:10.1098/rsif.2014.1326. ISSN 1742-5689. PMC 4387522. PMID 25694539.

- ^ Valdovinos, Claudio; Rüth, Maximillian (1 September 2005). "Nacellidae limpets of the southern end of South America: taxonomy and distribution". Revista Chilena de Historia Natural. 78 (3): 497–517. doi:10.4067/S0716-078X2005000300011. ISSN 0716-078X.

- ^ Ukmar-Godec, Tina; Kapun, Gregor; Zaslansky, Paul; Faivre, Damien (1 December 2015). "The giant keyhole limpet radular teeth: A naturally-grown harvest machine". Journal of Structural Biology. 192 (3): 392–402. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2015.09.021. PMC 4658332. PMID 26433029.

- ^ a b c d e f Sone, Eli D.; Weiner, Steve; Addadi, Lia (1 November 2005). "Morphology of Goethite Crystals in Developing Limpet Teeth: Assessing Biological Control over Mineral Formation". Crystal Growth & Design. 5 (6): 2131–2138. doi:10.1021/cg050171l. ISSN 1528-7483.

- ^ a b c d Weiner, Steve; Addadi, Lia (4 August 2011). "Crystallization Pathways in Biomineralization". Annual Review of Materials Research. 41 (1): 21–40. Bibcode:2011AnRMS..41...21W. doi:10.1146/annurev-matsci-062910-095803.

- ^ Sigel, Astrid; Sigel, Helmut; Sigel, Roland K. O. (2008). Biomineralization: From Nature to Application. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470986318.

- ^ Sone, Eli D.; Weiner, Steve; Addadi, Lia (1 June 2007). "Biomineralization of limpet teeth: A cryo-TEM study of the organic matrix and the onset of mineral deposition". Journal of Structural Biology. 158 (3): 428–44. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2007.01.001. PMID 17306563.

- ^ Gao, Huajian; Ji, Baohua; Jäger, Ingomar L.; Arzt, Eduard; Fratzl, Peter (13 May 2003). "Materials become insensitive to flaws at nanoscale: Lessons from nature". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (10): 5597–5600. doi:10.1073/pnas.0631609100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 156246. PMID 12732735.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lu, Dun; Barber, Asa H. (7 June 2012). "Optimized nanoscale composite behaviour in limpet teeth". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 9 (71): 1318–24. doi:10.1098/rsif.2011.0688. ISSN 1742-5689. PMC 3350734. PMID 22158842.

- ^ Chicot, D.; Mendoza, J.; Zaoui, A.; Louis, G.; Lepingle, V.; Roudet, F.; Lesage, J. (October 2011). "Mechanical properties of magnetite (Fe3O4), hematite (α-Fe2O3) and goethite (α-FeO·OH) by instrumented indentation and molecular dynamics analysis". Materials Chemistry and Physics. 129 (3): 862–70. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2011.05.056.

- ^ Cruz, R.; Farina, M. (4 March 2005). "Mineralization of major lateral teeth in the radula of a deep-sea hydrothermal vent limpet (Gastropoda:Neolepetopsidae)". Marine Biology. 147 (1): 163–68. doi:10.1007/s00227-004-1536-y. S2CID 84563618.

- ^ Mann, S.; Perry, C. C.; Webb, J.; Luke, B.; Williams, R. J. P. (22 March 1986). "Structure, Morphology, Composition and Organization of Biogenic Minerals in Limpet Teeth". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 227 (1247): 179–90. Bibcode:1986RSPSB.227..179M. doi:10.1098/rspb.1986.0018. ISSN 0962-8452. S2CID 89570130.

- ^ Davies, Mark S.; Proudlock, Donna J.; Mistry, A. (May 2005). "Metal Concentrations in the Radula of the Common Limpet, Patella vulgata L., from 10 Sites in the UK". Ecotoxicology. 14 (4): 465–75. doi:10.1007/s10646-004-1351-8. PMID 16385740. S2CID 25235604.

- ^ "Luminescent limpet". Landcare Research. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ "Identifying British freshwater snails: Ancylidae". The Conchological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ a b Limpet fights off a starfish - The Secret Life of Rock Pools - Preview - BBC Four, 12 April 2013, retrieved 20 October 2022

- ^ Andrews, C.; Williams, R. B. G. (2000). "Limpet erosion of chalk shore platforms in southeast England". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 25 (12): 1371–1381. Bibcode:2000ESPL...25.1371A. doi:10.1002/1096-9837(200011)25:12<1371::AID-ESP144>3.0.CO;2-#.

- ^ Gray, William (18 September 2013). "Escape to the Isles of Scilly". Wanderlust.

- ^ Lear, Edward (1907). Letters of Edward Lear. T. Fisher Unwin. p. 165.

- ^ Grindle, Simon (1964). The Loving Limpet and Other Peculiarities. Illustrated by Alan Todd. Newcastle: Oriel Press.