Olisipo

| Location | Portugal |

|---|---|

| Region | Lisbon metropolitan area |

| Coordinates | 38°42′44″N 9°08′02″W / 38.7122204°N 9.1339731°W |

Municipium Cives Romanorum Felicitas Julia Olisipo (in Latin: Olisippo or Ulyssippo ; in Greek: Ὀλισσιπών, Olissipṓn, or Ὀλισσιπόνα, Olissipóna) was the ancient name of modern-day Lisbon while it was part of the Roman Empire.

Background

[edit]

During the Punic wars, after the defeat of Hannibal the Romans decided to deprive Carthage of its most valuable possession, Hispania. After the defeat of the Carthaginians by Scipio Africanus in eastern Hispania, the pacification of western Hispania was led by Consul Decimus Junius Brutus Callaicus. He obtained the alliance of Olisipo (which sent men to fight alongside the Roman legions against the northwestern Celtic tribes) by integrating it into the Roman Republic in 138 BC.

Between 31 BC and 27 BC the city became a municipium.[1] Local authorities were granted self-rule over a territory that extended 50 kilometres (31 miles). Exempt from taxes, its citizens (belonging to the Galeria tribe) were given the privileges of Roman citizenship (Civium Romanorum), and the city was integrated within the Roman province of Lusitania (whose capital was Emerita Augusta). Decimus Junius Brutus Callaicus also fortified the city, building city walls as a defence against Lusitanian raids and rebellions.

Among the majority of Latin speakers lived a large minority of Greek traders and slaves. Lisbon's name was written Ulyssippo in Latin by the geographer Pomponius Mela.[2] The city population is estimated to have been around 30,000 at the time.

Earthquakes were documented in 60 BC, several between 47 and 44 BC, several in 33 AD, and a strong quake in 382 AD, but the exact amount of damage to the city is unknown.

The city

[edit]Buildings

[edit]During the time of Augustus (63 BC to 14 AD) the Romans built a large theatre (which was restored in 57 AD on the order of Caius Heius Primus).[3][4]

The galleries underneath the current Rua da Prata date from 20–35 AD;[5] they were rebuilt in 330 AD.[6] Uncovered in 1771 following Lisbon's devastating earthquake, the true purpose of these underground Roman passages has been subject to varying interpretations. Contemporary consensus leans towards them being a cryptoporticus—a structural innovation of the Roman Empire times, used to stabilize and level the ground for significant constructions, particularly in uneven terrains.[7]

The Thermae Cassiorum (Cassian Baths, named for Quintus Cassius Longinus and Lucius Cassius, were built in 44 AD. The building was renovated in 336 AD.[6][8][9][10][11]

Several temples were built in the city, dedicated to Jupiter, Concordia, Livia, Diana or Minerva (on the castle hill), Cybele (near current Largo da Madalena), Tethys (current São Nicolau church) and Idae Phrygiae (an uncommon cult from Asia Minor), to the Imperial Cult and to Vestal Virgins (in Chelas).[12]

A large necropolis from the 1st–4th centuries AD existed under Praça da Figueira[13] and it is known that a large forum (probably in current Largo dos Lóis) and an aqueduct were built.

A circus and hippodrome was built around the 3rd or 4th century AD.

Buildings such as insulae (multi-storied apartment buildings) existed in the area between the modern castle hill and downtown.

The city wall was strengthened in the 4th to 5th century AD, and around the city there were also bridges (in Sacavém and Alcântara) and villae.

-

Lisbon Roman theatre

-

Roman theatre stone re-used in the Lisbon Cathedral

-

Part of the old city wall

-

Rua dos Correeiros Archaeological Centre

Economy

[edit]Economically, Olisipo was known for its garum, a sort of fish sauce highly prized by the elites of the Empire and exported in amphorae to Rome and other cities. Wine, salt and the city's famously fast horses were also exported.

The city came to be very prosperous through suppression of piracy and technological advances, which allowed a boom in the trade with the newly Roman Provinces of Britannia (particularly Cornwall) and the Rhine, and through the introduction of Roman culture to the tribes living by the river Tagus in the interior of Hispania.

The city was connected by a broad road to Western Hispania's two other large cities, Bracara Augusta in the province of Tarraconensis (today's Portuguese Braga), and Emerita Augusta, the capital of Lusitania (now Mérida in Spain).

Government

[edit]The city was ruled by an oligarchical council dominated by two families, the Julii and the Cassiae. The Caecilli also held some power. Petitions are recorded addressed to the governor of the province in Emerita and to Emperor Tiberius, such as one requesting help dealing with "sea monsters" allegedly responsible for shipwrecks.

Around 80 BC, the Roman Quintus Sertorius led a rebellion against the dictator Sulla. During this period, he organized the tribes of Lusitania (and Hispania) and was on the verge of forming an independent province in the Sertorian War when he died.

The city was administered by two duumviri and two aediles.

- Lucius Iulius Maelo Caudicus was one of the duumviri in the 1st century AD.

- Lucius Iulius Iustus (son of Lucius Iulius Reburrus) was one of the city aedils in the 1st or 2nd century AD.[14]

Between 140 and 150 Lucius Statius Quadratus, a governor, was in Olisipo. In 185 Sextus Tigidius Perennis, governor of Lusitania, visited the region. Between 200 and 209 Junius Celanius, a governor, also came to Olisipo.

Lucidius was the native Roman governor of the city in 468, having helped the Suebi under Remismund to take it.

Religion

[edit]Olisipo, like most great cities in the Western Empire, was a centre for the dissemination of Christianity. Its first attested Bishop was St. Potamius (c. 356), and there were several martyrs killed during persecutions, such as the Diocletianic Persecution; Verissimus, Maxima, and Julia are the most significant names. According to legend, the three were sons of a Roman senator, martyred in Lisbon in the 4th century, under the Roman governor Ageian or Tarquinius in the time of Emperor Diocletian. A temple was then built in the Campolide area, whose ruins still existed in the Middle Ages [citation needed]. The relics of the saints are kept in the Santos-o-Velho Church.[15]

In the middle of the 4th century the Olisipo diocesis was formed.[16]

There is also the legend of Saint Ginés (São Gens), presented as one of the first martyr bishops of Lisbon and remembered in the Nossa Senhora do Monte chapel.

At the end of Roman rule, Olisipo was one of the first Christian cities.

Roman architectural remains in the region

[edit]-

Roman roads in Hispania

-

Roman dam of Belas, near Lisbon

The city was a caput viarium of the Roman road to Bracara Augusta and the three roads to Emerita Augusta. Olisipo controlled a vast region, bordered by the Alcabrichel and Ota rivers in the north.

The territory includes the following Roman archaeological finds, known settlements or place names:

In the current Sintra municipality

[edit]- Archaeological Site of Alto da Vigia[17] (Praia das Maçãs, Sintra)

- Archaeological Site of Colaride[18][19] (Alto de Colaride, Sintra)

- Archaeological Museum of São Miguel de Odrinhas[20] (Odrinhas, Sintra)

- Roman dam of Belas[21] (Belas, Sintra)

- Roman bridge at Catribana[22] (Catribana, Sintra)

- Roman bridge at Albarraque (Rio de Mouro, Sintra)

- Roman bridge at Várzea de Baixo[23] (Colares (Sintra))

- Roman bridge at Cheleiros[24] (Cheleiros, Sintra)

- Roman villa of Santo André de Almoçageme[25] (Almoçageme, Sintra)

- Roman villa of Amoreira (São João das Lampas, Sintra)

- Roman villa of Barros do Casal Silvério (Montelavar, Sintra)

- Roman villa of Granja dos Serrões[26] (Pêro Pinheiro, Sintra)

- Roman villa of Corrais do Chão (Sintra)

- Roman villa of São Marcos (São Marcos, Sintra)

- Roman site of Vila Velha (Sintra)

- Vicus of Faião (Terrugem, possible location for Chretina)

- Roman mine of Monte Suimo (Serra da Carregueira, Sintra)

- Fountain of Armés (Terrugem, Sintra)

- Roman villa of Lugar do Mercador (Mucifal, Sintra)

- Promontorium Lunae (Cabo da Roca, Sintra)

- Mons Lunae (Serra de Sintra)

In the current Cascais municipality

[edit]- Roman villa of Alto da Cidreira[27] (Alto da Cidreira, Cascais)

- Roman villa of Vilares[28] (Murches, Cascais)

- Roman villa of Casais Velhos[29] (Areia, Cascais)

- Roman villa of Outeiro de Polima or Freiria[30][31] (São Domingos de Rana, Cascais)

- Archaeological Site of Espigão das Ruivas[32] (Guincho Velho, Cascais)

- Roman villa of Miroiço[33] (Manique de Baixo, Cascais)

In the current Amadora municipality

[edit]In the current Torres Vedras municipality

[edit]- Roman baths of Cucos (another possible location for Chretina) (Cucos, Torres Vedras)

- Roman villa of Freiria (Torres Vedras)

In the current Loures municipality

[edit]- Roman villa of Almoinhas[34] (Loures)

- Roman villa of Frielas[35] (Frielas, Loures)

- Roman bridge at Frielas

Fall of the Roman Empire

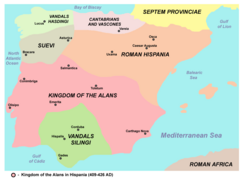

[edit]Alans

[edit]Lisbon suffered invasions from the Sarmatian Alans and the Germanic Vandals, who controlled the region from 409 to 429. The city was taken by the Visigoths under Wallia in 419.

Suebi

[edit]The Germanic Suebi, who established the Suebic Kingdom of Galicia (modern Galicia and northern Portugal), with capital in Bracara Augusta (today's Braga) from 409 to 585, also controlled the region of Lisbon for long periods of time.

In 457, while Framta was still ruling, Maldras led a large raid on Lusitania.[36] The raiders sacked Lisbon by pretending to come in peace and, once admitted by the citizens, plundering the city.[37]

In 468 the city of Lisbon was occupied by the Suebi under Remismund with the help of a native Roman governor named Lucidius, but in effect Roman dominion over the city had ended.

-

Kingdom of the Alans in Hispania (409-426 AD)

-

Iberian Peninsula around 500 AD

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Museu da Cidade (Lisboa) » Portugal Romano". Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2011-11-19.

- ^ Pomponius Mela; Gronovius; Schott; Núñez de Guzmán (1748). Pomponii Melae De situ orbis libri III cum notis integris Hermolai Barbari, Petri Joannis Olivarii, Fredenandi Nonii Pintiani, Petri Ciacconii, Andreae Schotti, Isaaci Vossii et Jacobi Gronovii, accedunt Petri Joannis Nunnesii Epistola de patria Pomponii Melae et adnotata... Et J. Perizonii Adnotata... curante A. Gronovio. apud Samuelem Luchtmans et Fil., Academiae typographos. p. 246.

- ^ "Museuteatroromano.pt | Registrado en DonDominio". www.museuteatroromano.pt. Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Do Teatro Grego ao Teatro Romano de Lisboa" [From the Greek Theater to the Roman Theater of Lisbon] (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-19.

- ^ "Sítio da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa: Página principal".

- ^ a b "Revista Municipal" (PDF). 1951. Retrieved 2024-05-31.

- ^ "Galerias Romanas: The Roman Galleries in Lisbon, Portugal". Roman Empire Times. 2024-04-22. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ "Centro Cultural de Cascais - Museu Nacional de Arqueologia - Museu Arqueológico de S. Miguel de Odrinhas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Fernandes, Lidia. "Capitel das Thermae Cassiorum de Olisipo" [Capital of the Thermae Cassiorum of Olisipo] (PDF). www.igespar.pt (in Portuguese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-07.

- ^ "O que a cave (Mal) esconde: Termas dos Cássios".

- ^ "HispaniaEpigraphica Online Database - Record Card".

- ^ Joaquim Antonio de Macedo (1874). A Guide to Lisbon and Its Environs, Including Cintra and Mafra ... Simpkin, Marshall. pp. 212–214.

- ^ ""Marcas de oleiro" em terra sigillata da Praça da Figueira (Lisboa): contribuição para o conhecimento da economia de Olisipo" [“Potter’s marks” on terra sigillata in Praça da Figueira (Lisbon): contribution to knowledge of the economy of Olisipo] (PDF). repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt. Retrieved 2024-05-31.

- ^ "Inscrições Romanas Do Termo De Loures" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ Cardoso, João Luís (November 2020). "As "Pedras do Martírio" dos Santos Mártires de Lisboa: confirmação das observações de Carlos Ribeiro (1813-1882)". Al-Madan. 23: 129–133. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ "Contributo para a caracterização do mundo rural olisiponense" [Contribution to the characterization of the rural world of Olisiponense] (PDF). repositorio.ul.pt. Retrieved 2024-05-31.

- ^ "POC – Programa Operacional da Cultura". Arqueologia.igespar.pt. Archived from the original on 2011-07-04. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Monumentos". Monumentos.pt. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Igespar Ip | Heritage". Igespar.pt. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Igespar Ip | Património" (in Portuguese). Igespar.pt. 1959-11-30. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Lisboa (Portugal)". Romanaqueducts.info. 2005-03-25. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ Portugal Romano (2011-09-18). "Ponte e via romana de Catribana (Sintra)". Portugalromano.com. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "POC – Programa Operacional da Cultura". Arqueologia.igespar.pt. Archived from the original on 2010-06-11. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Monumentos". Monumentos.pt. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Field Work of Santo André de Almoçageme – Museum of Odrinhas". Museuarqueologicodeodrinhas.pt. Archived from the original on 2012-04-24. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Igespar Ip | Património" (in Portuguese). Igespar.pt. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Igespar Ip | Património |" (in Portuguese). Igespar.pt. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Sem título 0". Neoepica.pt. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Monumentos". Monumentos.pt. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Monumentos". Monumentos.pt. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Igespar Ip | Património" (in Portuguese). Igespar.pt. 1990-07-17. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ Portugal Romano (2011-01-27). "Espigão das Ruivas – "Porto Touro"". Portugalromano.com. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Monumentos". Monumentos.pt. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Monumentos". Monumentos.pt. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ "Edição 43 – Loures e Odivelas". Jornal das Autarquias. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ Thompson, 167.

- ^ Thompson, 171.

External links

[edit]- Olisipo map

- Museu do Teatro Romano

- Vias romanas – outros percursos em Sintra

- Almoçageme e os itinerários das vias

- Os mais recentes achados epigráficos do Castelo de S. Jorge, Lisboa

- “Marcas de oleiro” em terra sigillata da Praça da Figueira (Lisboa) : contribuição para o conhecimento da economia de Olisipo (séc. I a.C. – séc. II d.C.)

![The Aqueduto Romano de Olisipo na Amadora [pt]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/Aquae_Ductus_photographed_by_P.G._de_Mendon%C3%A7a_at_Gargantada%2C_AMADORA%2C_PORTUGAL_%28Wikidata_Q93896734%29.jpg/271px-Aquae_Ductus_photographed_by_P.G._de_Mendon%C3%A7a_at_Gargantada%2C_AMADORA%2C_PORTUGAL_%28Wikidata_Q93896734%29.jpg)