Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2020) |

The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee,[a] abbreviated as JAC,[b] was an organization that was created in the Soviet Union during World War II to influence international public opinion and organize political and material support for the Soviet fight against Nazi Germany, particularly from the West.[1] It was organized by the Jewish Bund leaders Henryk Erlich and Victor Alter, upon an initiative of Soviet authorities, in fall 1941; both were released from prison in connection with their participation.[2][3] Following their re-arrest, in December 1941, the Committee was reformed on Joseph Stalin's order[4] in Kuibyshev in April 1942 with the official support of the Soviet authorities. In 1952, as part of the persecution of Jews in the last year part of Stalin's rule (for example, the "Doctors' plot"), most prominent members of the JAC were arrested on trumped-up spying charges, tortured, tried in secret proceedings, and executed in the basement of Lubyanka Prison. Stalin and elements of the Ministry of State Security were worried about their influence and connections with the West.[1] They were officially rehabilitated in 1988.

Activities

[edit]

Solomon Mikhoels, the popular actor and director of the Moscow State Jewish Theatre, was appointed the JAC chairman. The JAC's newspaper in Yiddish was called Eynigkayt (אייניקייט "Unity", Cyrillic: Эйникейт).

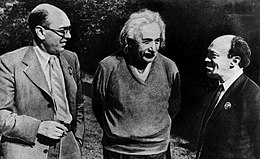

The JAC broadcast pro-Soviet propaganda to foreign audiences, assuring them of the absence of antisemitism in the Soviet Union. In 1943, Mikhoels and Itzik Feffer, the first official representatives of the Soviet Jewry allowed to visit the West, embarked on a seven-month tour to the United States, Mexico, Canada and the United Kingdom to increase their support for the Lend-Lease. In the US, they were welcomed by a National Reception Committee chaired by Albert Einstein and by B.Z. Goldberg, Sholem Aleichem's son-in-law, and American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. The largest pro-Soviet rally ever in the United States was held on July 8 at the Polo Grounds, where 50,000 people listened to Mikhoels, Feffer, Fiorello H. La Guardia, Sholem Asch, and Chairman of World Jewish Congress Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise. Among others, they met Chaim Weizmann, Charlie Chaplin, Marc Chagall, Paul Robeson and Lion Feuchtwanger.

In addition to the funds for the Soviet war effort – US$16 million raised in the US, $15 million in England, $1 million in Mexico, $750,000 in Mandatory Palestine – other help was also contributed: machinery, medical equipment, medicine, ambulances, clothes. On May 24, 1942, at the second meeting of the “representatives of the Jewish people”, a worldwide appeal for donations was made to collect money for the purchase of 1,000 tanks and 500 airplanes for the Red Army.[5] On July 16, 1943, Pravda reported: "Mikhoels and Feffer received a message from Chicago that a special conference of the Joint initiated a campaign to finance a thousand ambulances for the needs of the Red Army." The visit drew the attention of the American public to the necessity of entering the European war.

Persecution

[edit]

Towards the end and immediately after the war, the JAC became involved in documenting the Holocaust. This ran contrary to the official Soviet policy to present it as atrocities against all Soviet citizens, not acknowledging the specific genocide of the Jews.[6]

Committee members had international contacts especially in the US at the outset of the Cold War and this may have contributed to them later being accused of treason and espionage.

The contacts with American Jewish organizations resulted in the plan to publish The Black Book of Soviet Jewry simultaneously in the US and the Soviet Union, documenting the Holocaust and participation of Jews in the resistance movement. The Black Book was indeed published in New York City in 1946, but no Russian edition appeared. The typeface galleys were broken up in 1948, when the political situation of Soviet Jewry deteriorated.[7]

In January 1948, Mikhoels was killed in Minsk by Ministry of State Security agents who staged the murder as a car accident.[8] The members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested. They were charged with disloyalty, bourgeois nationalism, cosmopolitanism, and planning to establish Jewish autonomy in Crimea to serve US interests.

In January 1949, the Soviet mass media launched a massive propaganda campaign against "rootless cosmopolitans", unmistakably aimed at Jews. Markish observed at the time: "Hitler wanted to destroy us physically, Stalin wants to do it spiritually." On 12 August 1952, at least thirteen prominent Yiddish writers were executed in the event known as the "Night of the Murdered Poets" ("Ночь казненных поэтов").[9]

List of notable JAC members

[edit]The size of JAC fluctuated with time. According to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (200 Years Together), it grew to have about 70 members.

- Solomon Mikhoels (Chairman), the actor-director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater

- Solomon Lozovsky (Secretary), a former Soviet vice-minister of Foreign Affairs and the head of the Soviet Information Bureau

- Shakne Epshtein (Secretary and editor of the Eynikeyt newspaper)

- Itzik Feffer, a poet

- Ilya Ehrenburg, a writer

- Eli Falkovich, a writer

- Solomon Bregman, a deputy minister of State Control

- Aaron Katz, a Red Army general of the Stalin Military Academy

- Boris Shimeliovich, the Chief Surgeon of the Red Army and director of Botkin Hospital

- Joseph Yuzefovich, a historian

- Leib Kvitko, a poet

- Peretz Markish, a poet

- Isaak Nusinov, a linguist and literature critic

- David Bergelson, a writer

- David Hofstein, a poet

- Benjamin Zuskin, an actor

- Ilya Vatenberg, an editor

- Shlomo Shleifer, Chief Rabbi of Moscow

- Emilia Teumin, an editor

- Leon Talmy, a journalist, translator

- Khayke Vatenberg-Ostrowskaya, a translator

- Lina Stern, a biochemist, physiologist and humanist and the first female full member of the Russian Academy of Sciences

- Israel Fisanovich, submarine commander, Hero of the Soviet Union

- Shmuel Halkin, a poet

See also

[edit]- All-Slavic Anti-Fascist Committee

- History of the Jews in Russia and Soviet Union

- Yevsektsiya

- Doctors' plot

- History of anti-Semitism

- Vasily Grossman

- Polina Zhemchuzhina

- Jewish Bolshevism

- Jewish left

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Talya Zax (August 12, 2017). "65 Years Ago, The USSR Murdered Its Greatest Jewish Poets. What's Left Of Their Legacy?". The Forward. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

...they...were executed in the [Lubyanka Prison]'s basement.

- ^ Blatman, Daniel (8 July 2010) "Alter, Wiktor." Translated from the Hebrew by David Fachler. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Blatman, Daniel (6 August 2010). "Ehrlich, Henryk." Translated from the Hebrew by David Fachler. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Sebag-Montefiore, Simon. Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. 2003. page 560.

- ^ https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jewish-anti-fascist-committee

- ^ Shimon Redlich. "Stalin's Bureaucracy in Action: The Creation and Destruction of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee". The World Holocaust Remembrance Center.

- ^ Joshua Rubenstein (15 July 2001). ""Stalin's Secret Pogrom: The Postwar Inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee"". The New York Times.

- ^ Robert Conquest Reflections on a Ravaged Century (2000) ISBN 0-393-04818-7

- ^ Shimon Redlich (1969). "The Jewish Antifascist Committee in the Soviet Union". Jewish Social Studies. 31 (1): 25–36. JSTOR 4466454.

Further reading

[edit]- ISBN 0-300-08486-2 Stalin's Secret Pogrom: The Postwar Inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (by Joshua Rubenstein)

- The Black Book (Chornaya Kniga), compiled and edited by: Vasily Grossman and Ilya Erenburg

External links

[edit]- Memorandum concerning the Jewish Antifascist Committee sent to Mikhail Suslov in June 1946 (Library of Congress archives)

- JAC case (in Russian language) at International Democracy Fund Archives

- Stalin's secret pogrom: Commies who became politically incorrect (By Chuck Morse)

- Beyond the Pale: The history of Jews in Russia

- Group photo of the members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

- Stalin’s Bureaucracy in Action: The Creation and Destruction of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee Shimon Redlich, War, Holocaust and Stalinism: A Documented Study of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in the USSR, Luxembourg: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1995. Reviewed by Theodore H. Friedgut

- (in Russian) JAC and its end

- (in Russian) JAC, Soviet repressions and its demise

- 1942 establishments in the Soviet Union

- Anti-fascist organizations

- Bundism in Europe

- Jewish political organizations

- Soviet state institutions

- Jews and Judaism in the Soviet Union

- Political repression in the Soviet Union

- Organizations established in 1942

- Jewish anti-fascists

- Defunct Jewish organizations

- Jewish political movements