Grattan Bridge

Grattan Bridge Droichead Grattan | |

|---|---|

Grattan Bridge | |

| Coordinates | 53°20′45″N 6°16′04″W / 53.3457°N 6.2678°W |

| Crosses | River Liffey |

| Locale | Dublin, Ireland |

| Preceded by | O'Donovan Rossa Bridge |

| Followed by | Millennium Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Material | Stone, iron |

| No. of spans | 5 (2 semicircular & 3 elliptical arches) |

| History | |

| Designer | William Robinson (1677-78) George Semple (1750s build) Bindon Blood Stoney & Parke Neville (1870s widening)[1] |

| Opened | Built 1676 - Essex Bridge Rebuilt 1753 - Essex Bridge Rebuilt 1872 - Grattan Bridge |

| Location | |

| |

Grattan Bridge (Irish: Droichead Grattan)[2] is a road bridge spanning the River Liffey in Dublin, Ireland, and joining Capel Street to Parliament Street and the south quays.

History

[edit]1st Essex bridge of 1676

[edit]The first bridge on this site was developed by Sir Humphrey Jervis in 1676 with William Robinson acting as adviser and contractor.[3][4][5] It was named as Essex Bridge to honour Arthur Capell, 1st Earl of Essex, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland who had also provided the finance for the construction of the bridge. It joined several of Jervis' developments (including Capel Street and Jervis Street) to the opposite side of the river and to Dublin Castle.

Essex Bridge was an arched stone structure with seven piers, and apparently partly constructed from the ruined masonry of nearby St. Mary's Abbey, Dublin on the northside.[1] In 1687 the bridge was damaged by a flood resulting in the loss of a hackney and two horses. The damage to the bridge was only partially repaired.[6]

2nd Essex bridge of 1753

[edit]

In 1751 the second most northerly pier collapsed and damaged the adjacent arches.[1]

Between 1753 and 1755 the bridge was rebuilt by George Semple, to correct flood and other structural damage and as one of the first initiatives of the Wide Streets Commission.[1] The new bridge included stone alcoves or niches on either side of the bridge in a similar manner to London Bridge.

In 1764, John Bush, an English traveller, visited Dublin and had the following to say about the bridge:

- "Over this river there are five bridges, one only of which deserves any notice, Essex-bridge, the lowest of all, which is really a well built, spacious and elegant bridge, with raised foot-paths, alcoves, and ballustrading, on the plan of Westminster-bridge, and about the same width, but not above one-fifth part so long" [7]

For much of the 18th century, Essex Bridge was the most easterly bridge on the Liffey and marked the furthest point upriver to which ships with masts could travel.[8] Many ships needed to travel this far upriver in order to berth in front of the old Custom House, the centre of merchant activity in the city from 1707 until 1791.

During this construction, some original features were removed, including the equestrian statue of George I, by John van Nost the Elder,[9] which was moved in 1798 to the gardens of the Mansion House. In 1937 it was bought by the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham, in front of which it still stands as of 2023.[9]

Grattan Bridge of 1874

[edit]From 1872, the bridge was further remodelled (on Westminster Bridge in London) by Parke Neville with further modifications by Bindon Blood Stoney, being widened and flattened with cast iron supports extended out from the stonework so as to carry pavements on either side of the roadway.[1] The bridge was (and is still) lit by ornate lamp standards also in cast iron.[4][10]

The bridge was reopened as Grattan Bridge in 1874, being named after Henry Grattan MP (1746-1820).

Later development

[edit]From 2002, Dublin City Council undertook a reconstruction of the bridge deck,[11] with granite paving for the footpaths and a set of benches with wooden seats and toughened glass backs.[12]

As part of what was intended to be a "European-style book market", in 2004 several temporary kiosks (prefabricated in Spain) were also controversially built on the bridge. Originally intended to create "a contemporary version of an inhabited bridge, such as the Ponte Vecchio in Florence",[13] these kiosks were later removed.[14]

Nomenclature

[edit]As is a tradition among Dubliners, the name used locally for the bridge will vary from Capel Street Bridge, to Grattan Bridge and the original Essex Bridge.

Gallery

[edit]-

The bridge at dusk

-

Looking east from the bridge along Wellington Quay

-

The eastern side of the bridge, looking north towards Capel Street

-

Detail of the Hippocampus figures along the bridge

-

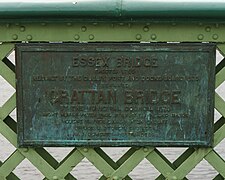

Plaque on the western side of the bridge. Commemorating the renaming of the bridge from Essex Bridge to Grattan Bridge.

-

Illustration of Essex Bridge and the statue of George I, taken from Brooking's 1720s map of Dublin, prior to Semple's rebuild of the 1750s

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Project history of Dublin's River Liffey bridges (PDF). Bridge Engineering 156 Issue BE4 (Report). Phillips & Hamilton. p. 162. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2005.

- ^ "Droichead Grattan / Grattan Bridge". Logainm.ie. Irish Placenames Commission. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Robinson, Sir William | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Grattan Bridge, Dublin". Archiseek. 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Overview | Grattan Bridge | Bridges of Dublin". www.bridgesofdublin.ie. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ Lennon, Colm; Montague, John (2010). John Roque's Dublin: A guide to the Georgian City. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy.

- ^ Bush, John (1769), Hibernia Curiosa: A Letter from a Gentleman in Dublin to his Friend at Dover in Kent, Giving a general View of the Manners, Customs, Dispositions, &c. of the Inhabitants of Ireland., London: London (W. Flexney); Dublin (J. Potts and J. Williams), p. 12

- ^ "Local History - Temple Bar". Templebardoc.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2006.

- ^ a b De Courcy, John (1988). Anna Liffey. The river of Dublin. Dublin: O'Brien Press.

- ^ "CO. DUBLIN, DUBLIN, ESSEX BRIDGE Dictionary of Irish Architects -". www.dia.ie. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ "Grattan Bridge - Timeline". bridgesofdublin.ie. Dublin City Council. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Council to move kiosks as book market idea fails". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 13 August 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Liffey kiosks are 'visual vandalism', council told". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 13 February 2004.

- ^ "Grattan Bridge kiosks gone". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 3 April 2008.