Elwyn (company)

Elwyn Inc. is a multi-state nonprofit organization based in Elwyn, Pennsylvania, in Middletown Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, United States, providing services for children and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and behavioral health challenges. Established in 1852, it provides education, rehabilitation, employment options, child welfare services, assisted living, respite care, campus and community therapeutic residential programs, and other support for daily living. Elwyn has operations in 8 states: Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, California, Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and North Carolina.

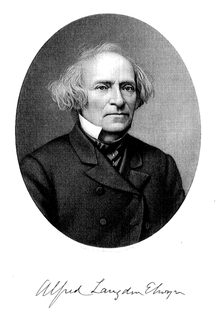

Elwyn and the Pennsylvania community where it is based are named for its founder, Dr. Alfred L. Elwyn, a physician, author and philanthropist.[1]

History

[edit]

Dr. Elwyn was one of the founding officers of the Pennsylvania Institution for the Instruction of the Blind in 1833.[2] He traveled to Boston for a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1849. He had promised to take a letter from Rachel Laird, a blind girl living in Philadelphia, to Laura Bridgman, who was a famous blind deaf mute in Boston. Bridgman was studying at the South Boston Institute for the Blind, and while there Elwyn visited a classroom for mentally disabled children run by teacher Dr. James B. Richards.[3]

Elwyn was impressed with Richards' work and resolved to do something similar in Pennsylvania. In 1852, with Richards, Elwyn established a training school for mentally disabled people in Germantown, Pennsylvania.[4] Their efforts to create interest and support within the academic community led to the incorporation of the Pennsylvania Training School in 1854, obtaining an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for $10,000, provisions for ten students, and a large farm near Media, PA.[5] The buildings were completed in 1859 and Elwyn, Richards, and 25 students moved in on September 1, 1859. The school was officially dedicated November 2, 1859 and industrialist John P. Crozer spoke at the ceremony. Elwyn became head of the school in 1870.[6]

Dr. Isaac N. Kerlin served the Army of the Potomac during the Civil War.[7] He was appointed Superintendent in 1864 at Elwyn and he served for 29 years. He created one of the first congregant settings for persons living with disabilities, including the establishment of a custodial and grounds-keeping department.[8]

Dr. Isaac N. Kerlin was superintendent of Elwyn in the early 20th century and was a proponent of sterilization procedures on those with intellectual disabilities. 98 sterilization procedures (59 males - 39 females) were conducted at Elwyn over the course of a ten-year period.[9]

Dr. Martin W. Barr and E. Arthur Whitney served for a combined 67 years as Presidents of Elwyn. They applied a medical model, or deficiency-driven approach, to the support of children and adults with disabilities. Dr. Barr authored the first American textbook on intellectual disabilities. During their time as presidents during the mid to late 19th century there were two societal shifts regarding intellectual disabilities: industrialization created more challenges for the full integration of people with intellectual disabilities back into their communities and Charles Darwin’s research on evolution led theories of selective breeding that led to the eugenics movement. Issac Kerlin, Henry Goddard of the Vineland School (now Elwyn), and Martin Barr were all proponents of this movement.[10]

During this time, Elwyn became a closed sanctuary emphasizing on a town model. The education emphasized manual training in printing, masonry, plant maintenance, shoe repair, farming, weaving, basketry, and direct care of individuals which meant individuals with less complex disability needs cared for person with greater disability needs.[11] Kerlin's town, or colony, model fit well into the growing popularity of custodialism, a practice which Barr readily endorsed and attempted to implement at Elwyn. Rooted in eugenic thought, custodialism called for life-long institutionalization of intellectually disabled people. One intention behind the custodial model was to ensure that intellectually disabled residents were not able to indulge in any sexual activity as they matured, mitigating the chance of any disabled offspring. Eugenicists like Barr believed that by keeping residents from passing on what they thought to be hereditary defects, they could gradually rid the world of disability.[12]

As President Whitney served post WW II, Elwyn became a cohesive community model which much of staff living on campus. A campus hospital served staff and clients. Institutional authority continued to be medical. Research into intellectual disabilities etiology and prevention as well as publishing findings were encouraged and done by many. Elwyn strived for self-sufficiency and agricultural productivity. By the end of Whitney’s tenure, the nation’s ideas on intellectual disabilities began to resemble the more modern versions of today. Dr. Gerald R. Clark was appointed President of Elwyn in 1960. During his administration, Elwyn made strides away from the self-contained institutional model and turned towards community-based special education and rehabilitation services for children and adults with disabilities. The emphasis shifted towards community-oriented training with a goal of assisting individuals to have a better role in society. Dr. Clark expanded programs so children enrolled in full-day educational programs. Elwyn developed vocational training courses and achieved licensure as a private trade school from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Instruction. The organization established a close working relationship with the Pennsylvania Bureau of Vocational Rehabilitation (BVR), which stationed a vocational counselor from the Bureau on Elwyn’s campus. The agency established sheltered workshops that provided training for individuals who lived both on and off the campus. In addition, he expanded services to accommodate day students from the community and started volunteer programs to stimulate and direct the interest of service clubs, church groups, and individuals. Dr. Marvin Kivitz became president of Elwyn in 1979. He expanded programs into other community settings and established a network of community-based rehabilitation centers and community living arrangements.[13]

In 1981, Elwyn acquired the Vineland Training School in Vineland, New Jersey. Elwyn depopulated the Vineland campus by developing a large community-based service system in South Jersey. Vineland Training School was known for the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, or “The Vineland Test,” which measures the personal and social skills of individuals from birth through adulthood, it is still used today.[14] Pearl Buck, who won both the Pulitzer and Nobel prizes for literature, sat on the Vineland Training Schools board of trustees; her daughter is laid to rest on the campus in Vineland.[15]

In 1991, Dr. Kivitz retired and Dr. Sandra S. Cornelius became president. Dr. Cornelius expanded child and adult behavioral program. In 1998, Elwyn was awarded the Mutually Agreed Upon Written Arrangement (MAWA) contract for the City of Philadelphia’s early intervention program. Under this contract, Elwyn manages all early intervention services for children ages three to five in the City of Philadelphia.[16]

On April 1, 2017, Dr. Cornelius retired and Charles S. McLister became Elwyn’s ninth President and Chief Executive Officer.[17] Elwyn acquired Fellowship Health Resources, founded in 1975 in Rhode Island by current board member, Alan Wichlei.[18] In 2023, it became a fully integrated service line called Elwyn’s Adult Behavioral Health Services after combining the FHR programs with existing Elwyn programs in Pennsylvania.[19] Between 2017 and 2021, McLister restructured management, invested in administrative and back-office infrastructure, supported the modernization of business processes, re-framed service lines and leadership, and consolidated and developed programs to meet modern needs.[20] In 2018, he sought and gained approval for a five-year strategic plan from Elwyn’s board of directors; the board and management team revisited the plan in April 2021 and issued an updated plan (2021-2024) shortly thereafter. As part of that plan, Elwyn created three distinct service lines, which are the core platforms for strategic growth and quality improvement: Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Services, Children’s Services, and Adult Behavioral Health Services.[19]

Elwyn has over 5,000 employees. In 2018, Elwyn served over 24,000 people with over 1,000 in group homes.[21]

Since its founding, Elwyn has had only nine presidents (sometimes referred to as superintendents). • James B. Richards (1852 to 1856) • Joseph Parrish, M.D. (1856 to 1864) • Alfred L. Elwyn, M.D. (Chairman and Acting Head, 1861 to 1863) • Isaac N. Kerlin, M.D. (1864 to 1893) • Martin W. Barr, M.D. (1893 to 1930) • E. Arthur Whitney, M.D. (1930 to 1960) • Gerald R. Clark, M.D. (1960 to 1979) • Marvin Kivitz, M.D. (1979 to 1991) • Sandra S. Cornelius, Ph.D. (1991 to 2017) • Charles S. McLister, M.A., M.B.A., (2017 to Present)

Locations

[edit]- Elwyn, founded 1852.

- Media, Pennsylvania, Main facility, established in 1859.

- Philadelphia, established in 1982.

- Wilmington, Delaware, established in 1974.

- Vineland, New Jersey, Vineland Training School, established 1888, merged with Elwyn in 1988.

- Elwyn California, independent affiliate, established in 1974.

- Israel Elwyn, independent, former affiliate, established in 1984.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schuster, Ken. "Getting to Know the History of Elwyn, PA". www.schusterlaw.com. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ Constitution, Charter and By-laws, and Documents Relating to the Pennsylvania Institution for the Instruction of the Blind, at Philadelphia. C. Sherman & Co. 1837. p. 18. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ "Elwyn History". Archived from the original on October 8, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Hurd, Henry Mills (1916). The Institutional Care of the Insane in the United States and Canada, Volume 3. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 504–510. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Hurd, Henry Mills. The institutional care of the insane in the United States and Canada. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 625–628. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Ashmeade, Henry Graham (1884). History of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co. pp. 625-628. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ Mellby, Julie L.; Levine, Emil (January 16, 2011). "Graphic Arts". The Mind Unveiled. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Ferguson, Philip M. (November 5, 2014). "Civil War Surgeon, Medical Educator, Philanthropist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Winzer, Margaret A. (1993). The History of Special Education From Isolation to Integration. Washington, D.C.: Galludet University Press. p. 302. ISBN 1-56368-018-1. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Ruswick, Brent (March 17, 2022). "Eugenics". Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ "American Institutions for the Feeble-Minded, 1876-1916" (PDF). ProQuest. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Chamberlain, Chelsea D. (2021). "Challenging Custodialism: Families and Eugenic Institutionalization at the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children at Elwyn". Journal of Social History. 55 (2) – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ Rosen, Marvin (September 1, 1992). "SERVICE DELIVERY IN AN INSTITUTION: A CASE STUDY". McGill Journal of Education / Revue des sciences de l'éducation de McGill. 27 (3). ISSN 1916-0666. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Chamberlain, Chelsea D.; Simon, Elliott (August 18, 2022). "The Elwyn Archives and Museum". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 89 (3). Penn State University Press: 480–486. doi:10.5325/pennhistory.89.3.0480. ISSN 2153-2109. S2CID 251759519. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Marko, Deborah M. (April 8, 2022). "Pearl S. Buck's daughter had an unmarked grave. Then a fan stepped in". thedailyjournal.com. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ "Special Education Hearing Officer" (PDF). Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Scanlon, Hunt (June 14, 2017). "The Tolan Group Recruits CEO for Elwyn". Hunt Scanlon Media. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ "FHR to Affiliate with Elwyn". fhr.net. July 26, 2018. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ a b Rose, Alex (April 29, 2023). "Elwyn looks to the future with major changes on Middletown campus". Delco Times. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Bjorkgren, David (December 10, 2019). "Elwyn Hires New Auditing and Consulting Firms". DELCO.Today. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Brubaker, Harold (June 5, 2020). "Elwyn, a 168-year-old lifeline for many families, is struggling under financial strain". www.inquirer.com. Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved September 1, 2021.