Elie Wiesel

Elie Wiesel | |

|---|---|

Wiesel in 1996 | |

| Born | Eliezer Wiesel September 30, 1928 Sighet, Kingdom of Romania |

| Died | July 2, 2016 (aged 87) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Sharon Gardens Cemetery, Valhalla, NY, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Subjects |

|

| Notable works | Night (1960) |

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse |

Marion Erster Rose (m. 1969) |

| Children | Elisha |

Eliezer "Elie" Wiesel (/ˈɛli viːˈzɛl/ EL-ee vee-ZEL or /ˈiːlaɪ ˈviːsəl/ EE-ly VEE-səl;[3][4][5] Yiddish: אליעזר "אלי" װיזל, romanized: Eliezer "Eli" Vizl; September 30, 1928 – July 2, 2016) was a Romanian-born American writer, professor, political activist, Nobel laureate, and Holocaust survivor. He authored 57 books, written mostly in French and English, including Night, a work based on his experiences as a Jewish prisoner in the Auschwitz and Buchenwald concentration camps.[6]

In his political activities Wiesel became a regular speaker on the subject of the Holocaust and remained a strong defender of human rights during his lifetime. He also advocated for many other causes like the state of Israel and against Hamas and victims of oppression including Soviet and Ethiopian Jews, the apartheid in South Africa, the Bosnian genocide, Sudan, the Kurds and the Armenian genocide, Argentina's Desaparecidos or Nicaragua's Miskito people.[7][8]

He was a professor of the humanities at Boston University, which created the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies in his honor. He was involved with Jewish causes and human rights causes and helped establish the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

Wiesel was awarded various prestigious awards including the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986.[9][10][11] He was a founding board member of the New York Human Rights Foundation and remained active in it throughout his life.[12][13]

Early life

Eliezer Wiesel was born in Sighet (now Sighetu Marmației), Maramureș, in the Carpathian Mountains of Romania.[14] His parents were Sarah Feig and Shlomo Wiesel. At home, Wiesel's family spoke Yiddish most of the time, but also German, Hungarian, and Romanian.[15][16] Wiesel's mother, Sarah, was the daughter of Dodye Feig, a Vizhnitz Hasid and farmer from the nearby village of Bocskó. Dodye was active and trusted within the community.

Wiesel's father, Shlomo, instilled a strong sense of humanism in his son, encouraging him to learn Hebrew and to read literature, whereas his mother encouraged him to study the Torah. Wiesel said his father represented reason, while his mother Sarah promoted faith.[17] Wiesel was instructed that his genealogy traced back to Rabbi Schlomo Yitzhaki (Rashi), and was a descendant of Rabbi Yeshayahu ben Abraham Horovitz ha-Levi.[18]

Wiesel had three siblings—older sisters Beatrice and Hilda, and younger sister Tzipora. Beatrice and Hilda survived the war, and were reunited with Wiesel at a French orphanage. They eventually emigrated to North America, with Beatrice moving to Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Tzipora, Shlomo, and Sarah did not survive the Holocaust.

Imprisonment and orphaning during the Holocaust

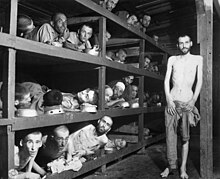

In March 1944, Germany occupied Hungary, thus extending the Holocaust into Northern Transylvania as well.[a] Wiesel was 15, and he, with his family, along with the rest of the town's Jewish population, was placed in one of the two confinement ghettos set up in Máramarossziget (Sighet), the town where he had been born and raised. In May 1944, the Hungarian authorities, under German pressure, began to deport the Jewish community to the Auschwitz concentration camp, where up to 90 percent of the people were murdered on arrival.[20]

Immediately after they were sent to Auschwitz, his mother and his younger sister were murdered.[20] Wiesel and his father were selected to perform labor so long as they remained able-bodied, after which they were to be murdered in the gas chambers. Wiesel and his father were later deported to the concentration camp at Buchenwald. Until that transfer, he admitted to Oprah Winfrey, his primary motivation for trying to survive Auschwitz was knowing that his father was still alive: "I knew that if I died, he would die."[21] After they were taken to Buchenwald, his father died before the camp was liberated.[20] In Night,[22] Wiesel recalled the shame he felt when he heard his father being beaten and was unable to help.[20][23]

Wiesel was tattooed with inmate number "A-7713" on his left arm.[24][25] The camp was liberated by the U.S. Third Army on April 11, 1945, when they were just prepared to be evacuated from Buchenwald.[26]

Post-war career as a writer

France

After World War II ended and Wiesel was freed, he joined a transport of 1,000 child survivors of Buchenwald to Ecouis, France, where the Œuvre de secours aux enfants (OSE) had established a rehabilitation center. Wiesel joined a smaller group of 90 to 100 boys from Orthodox homes who wanted kosher facilities and a higher level of religious observance; they were cared for in a home in Ambloy under the directorship of Judith Hemmendinger. This home was later moved to Taverny and operated until 1947.[27][28]

Afterwards, Wiesel traveled to Paris where he learned French and studied literature, philosophy and psychology at the Sorbonne.[20] He heard lectures by philosopher Martin Buber and existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre and he spent his evenings reading works by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Franz Kafka, and Thomas Mann.[29]

By the time he was 19, he had begun working as a journalist, writing in French, while also teaching Hebrew and working as a choirmaster.[30] He wrote for Israeli and French newspapers, including Tsien in Kamf (in Yiddish).[29]

In 1946, after learning of the Irgun's bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, Wiesel made an unsuccessful attempt to join the underground Zionist movement. In 1948, he translated articles from Hebrew into Yiddish for Irgun periodicals, but never became a member of the organization.[31] In 1949, he traveled to Israel as a correspondent for the French newspaper L'arche. He then was hired as Paris correspondent for the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth, subsequently becoming its roaming international correspondent.[32]

Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever. Never shall I forget that nocturnal silence which deprived me, for all eternity, of the desire to live. Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never.

For ten years after the war, Wiesel refused to write about or discuss his experiences during the Holocaust. He began to reconsider his decision after a meeting with the French author François Mauriac, the 1952 Nobel Laureate in Literature who eventually became Wiesel's close friend. Mauriac was a devout Christian who had fought in the French Resistance during the war. He compared Wiesel to "Lazarus rising from the dead", and saw from Wiesel's tormented eyes, "the death of God in the soul of a child".[33][34] Mauriac persuaded him to begin writing about his harrowing experiences.[29]

Wiesel first wrote the 900-page memoir Un di velt hot geshvign (And the World Remained Silent) in Yiddish, which was published in abridged form in Buenos Aires.[35] Wiesel rewrote a shortened version of the manuscript in French, La Nuit, in 1955. It was translated into English as Night in 1960.[36] The book sold few copies after its initial publication, but still attracted interest from reviewers, leading to television interviews with Wiesel and meetings with writers such as Saul Bellow.

As its profile rose, Night was eventually translated into 30 languages with ten million copies sold in the United States. At one point film director Orson Welles wanted to make it into a feature film, but Wiesel refused, feeling that his memoir would lose its meaning if it were told without the silences in between his words.[37] Oprah Winfrey made it a spotlight selection for her book club in 2006.[20]

United States

In 1955, Wiesel moved to New York as foreign correspondent for the Israel daily, Yediot Ahronot.[32] In 1969, he married Austrian Marion Erster Rose, who also translated many of his books.[32] They had one son, Shlomo Elisha Wiesel, named after Wiesel's father.[32][38]

In the U.S., he eventually wrote over 40 books, most of them non-fiction Holocaust literature, and novels. As an author, he was awarded a number of literary prizes and is considered among the most important in describing the Holocaust from a highly personal perspective.[32] As a result, some historians credited Wiesel with giving the term Holocaust its present meaning, although he did not feel that the word adequately described that historical event.[39] In 1975, he co-founded the magazine Moment with writer Leonard Fein.

The 1979 book and play The Trial of God are said to have been based on his real-life Auschwitz experience of witnessing three Jews who, close to death, conduct a trial against God, under the accusation that He has been oppressive towards the Jewish people.[40]

Wiesel also played a role in the initial success of The Painted Bird by Jerzy Kosinski by endorsing it before it became known the book was fiction and, in the sense that it was presented as all Kosinski's true experience, a hoax.[41][42]

Wiesel published two volumes of memoirs. The first, All Rivers Run to the Sea, was published in 1994 and covered his life up to the year 1969. The second, titled And the Sea is Never Full and published in 1999, covered the years from 1969 to 1999.[43]

Political activism

Wiesel and his wife, Marion, started the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity in 1986. He served as chairman of the President's Commission on the Holocaust (later renamed the US Holocaust Memorial Council) from 1978 to 1986, spearheading the building of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.[44][45] Sigmund Strochlitz was his close friend and confidant during these years.[46]

The Holocaust Memorial Museum gives the Elie Wiesel Award to "internationally prominent individuals whose actions have advanced the Museum's vision of a world where people confront hatred, prevent genocide, and promote human dignity".[47] The Foundation had invested its endowment in money manager Bernard L. Madoff's investment Ponzi scheme, costing the Foundation $15 million and Wiesel and his wife much of their own personal savings.[48][49]

Support for Israeli government policy

In 1982, at the request of the Israeli Foreign Ministry, Wiesel agreed to resign from his position as chairman of a planned international conference on the Holocaust and the Armenian genocide. Wiesel then worked with the Foreign Ministry in its attempts to get the conference either canceled or to remove all discussion of the Armenian genocide from it, and to those ends he provided the Foreign Ministry with internal documents on the conference's planning and lobbied fellow academics to not attend the conference.[50]

During his lifetime, Wiesel had deflected questions on the topic of the Israeli settlements, claiming to abstain from commenting on Israel's internal debates.[51] According to Hussein Ibish, despite this position, Wiesel had gone on record as supporting the idea of expanding Jewish settlements into the Palestinian territories conquered by Israel during the 6 Day War; such settlements are considered illegal by the international community.[52]

Awards and activism

Wiesel was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 for speaking out against violence, repression, and racism. The Norwegian Nobel Committee described Wiesel as "one of the most important spiritual leaders and guides in an age when violence, repression, and racism continue to characterize the world" and called him a "messenger to mankind". It also stressed that Wiesel's commitment originated in the sufferings of the Jewish people but that he expanded it to embrace all repressed peoples and races.[9][10][11]

In his acceptance speech he delivered a message "of peace, atonement, and human dignity". He explained his feelings: "Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant."[53]

He received many other prizes and honors for his work, including the Congressional Gold Medal in 1985, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and The International Center in New York's Award of Excellence.[54] He was also elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1996.[55]

Wiesel co-founded Moment magazine with Leonard Fein in 1975. They founded the magazine to provide a voice for American Jews.[56] He was also a member of the International Advisory Board of NGO Monitor.[57]

A staunch opponent of the death penalty, Wiesel stated that he thought that even Adolf Eichmann should not have been executed.[58]

In April 1999, Wiesel delivered the speech "The Perils of Indifference" in Washington D.C., criticizing the people and countries who chose to be indifferent while the Holocaust was happening.[59] He defined indifference as being neutral between two sides, which, in this case, amounts to overlooking the victims of the Holocaust. Throughout the speech, he expressed the view that a little bit of attention, either positive or negative, is better than no attention at all.[60]

In 2003, he discovered and publicized the fact that at least 280,000 Romanian and Ukrainian Jews, along with other groups, were massacred in Romanian-run death camps.[61]

In 2005, he gave a speech at the opening ceremony of the new building of Yad Vashem, the Israeli Holocaust History Museum:

I know what people say – it is so easy. Those that were there won't agree with that statement. The statement is: it was man's inhumanity to man. NO! It was man's inhumanity to Jews! Jews were not killed because they were human beings. In the eyes of the killers they were not human beings! They were Jews![62]

In early 2006, Wiesel accompanied Oprah Winfrey as she visited Auschwitz, a visit which was broadcast as part of The Oprah Winfrey Show.[63] On November 30, 2006, Wiesel received a knighthood in London in recognition of his work toward raising Holocaust education in the United Kingdom.[64]

In September 2006, he appeared before the UN Security Council with actor George Clooney to call attention to the humanitarian crisis in Darfur. When Wiesel died, Clooney wrote, "We had a champion who carried our pain, our guilt, and our responsibility on his shoulders for generations."[65]

In 2007, Wiesel was awarded the Dayton Literary Peace Prize's Lifetime Achievement Award.[66] That same year, the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity issued a letter condemning Armenian genocide denial, a letter that was signed by 53 Nobel laureates including Wiesel. Wiesel repeatedly called Turkey's 90-year-old campaign to downplay its actions during the Armenian genocide a double killing.[67]

In 2009, Wiesel criticized the Vatican for lifting the excommunication of controversial bishop Richard Williamson, a member of the Society of Saint Pius X.[68] The excommunication was later reimposed.

In June 2009, Wiesel accompanied US President Barack Obama and German Chancellor Angela Merkel as they toured the Buchenwald concentration camp.[69] Wiesel was an adviser at the Gatestone Institute.[70] In 2010, Wiesel accepted a five-year appointment as a Distinguished Presidential Fellow at Chapman University in Orange County, California. In that role, he made a one-week visit to Chapman annually to meet with students and offer his perspective on subjects ranging from Holocaust history to religion, languages, literature, law and music.[71]

In July 2009, Wiesel announced his support to the minority Tamils in Sri Lanka. He said that, "Wherever minorities are being persecuted, we must raise our voices to protest ... The Tamil people are being disenfranchised and victimized by the Sri Lanka authorities. This injustice must stop. The Tamil people must be allowed to live in peace and flourish in their homeland."[72][73][74]

In 2009, Wiesel returned to Hungary for his first visit since the Holocaust. During this visit, Wiesel participated in a conference at the Upper House Chamber of the Hungarian Parliament, met Prime Minister Gordon Bajnai and President László Sólyom, and made a speech to the approximately 10,000 participants of an anti-racist gathering held in Faith Hall.[75][76] However, in 2012, he protested against "the whitewashing" of Hungary's involvement in the Holocaust, and he gave up the Great Cross award he had received from the Hungarian government.[77]

Wiesel was active in trying to prevent Iran from making nuclear weapons, stating that, "The words and actions of the leadership of Iran leave no doubt as to their intentions".[78] He also condemned Hamas for the "use of children as human shields" during the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict by running an ad in several large newspapers.[79] The Times refused to run the advertisement, saying, "The opinion being expressed is too strong, and too forcefully made, and will cause concern amongst a significant number of Times readers."[80][81]

Wiesel often emphasized the Jewish connection to Jerusalem, and criticized the Obama administration for pressuring Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to halt East Jerusalem Israeli settlement construction.[82][83] He stated that "Jerusalem is above politics. It is mentioned more than six hundred times in Scripture—and not a single time in the Koran ... It belongs to the Jewish people and is much more than a city".[84][85]

Teaching

Wiesel held the position of Andrew Mellon Professor of the Humanities at Boston University from 1976,[86] teaching in both its religion and philosophy departments.[87] He became a close friend of the president and chancellor John Silber.[88] The university created the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies in his honor.[86] From 1972 to 1976 Wiesel was a Distinguished Professor at the City University of New York and member of the American Federation of Teachers.[89][90]

In 1982 he served as the first Henry Luce Visiting Scholar in Humanities and Social Thought at Yale University.[87] He also co-instructed Winter Term (January) courses at Eckerd College, St. Petersburg, Florida. From 1997 to 1999 he was Ingeborg Rennert Visiting professor of Judaic Studies at Barnard College of Columbia University.[91]

Personal life

In 1969 he married Marion Erster Rose, who originally was from Austria and also translated many of his books.[32][92] They had one son, Shlomo Elisha Wiesel, named after Wiesel's father.[32][38] The family lived in Greenwich, Connecticut.[93]

Wiesel was attacked in a San Francisco hotel by 22-year-old Holocaust denier Eric Hunt in February 2007, but was not injured. Hunt was arrested the following month and charged with multiple offenses.[94][95]

In May 2011, Wiesel served as the Washington University in St. Louis commencement speaker.[96]

In February 2012, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints performed a posthumous baptism for Simon Wiesenthal's parents without proper authorization.[97] After his own name was submitted for proxy baptism, Wiesel spoke out against the unauthorized practice of posthumously baptizing Jews and asked presidential candidate and Latter-day Saint Mitt Romney to denounce it. Romney's campaign declined to comment, directing such questions to church officials.[98]

Death and aftermath

Wiesel died on the morning of July 2, 2016, at his home in Manhattan, aged 87. After a private funeral service was conducted in honor of him at the Fifth Avenue Synagogue, he was buried at the Sharon Gardens Cemetery in Valhalla, New York, on July 3.[48][99][100][101][102]

Utah senator Orrin Hatch paid tribute to Wiesel in a speech on the Senate floor the following week, in which he said that "With Elie's passing, we have lost a beacon of humanity and hope. We have lost a hero of human rights and a luminary of Holocaust literature."[103]

In 2018, antisemitic graffiti was found on the house where Wiesel was born.[104]

Awards and honors

- Prix de l'Université de la Langue Française (Prix Rivarol) for The Town Beyond the Wall, 1963.[105]

- National Jewish Book Award for The Town Beyond the Wall, 1965.[105][106]

- Ingram Merrill award, 1964.[107]

- Prix Médicis for A Beggar in Jerusalem, 1968.[105]

- National Jewish Book Award for Souls on Fire: Portraits and Legends of Hasidic Masters, 1973.[108]

- Jewish Heritage Award, Haifa University, 1975.[107]

- Holocaust Memorial Award, New York Society of Clinical Psychologists, 1975.[107]

- S.Y. Agnon Medal, 1980.[107]

- Jabotinsky Medal, State of Israel, 1980.[107]

- Prix Livre Inter, France, for The Testament, 1980.[105]

- Grand Prize in Literature from the City of Paris for The Fifth Son, 1983.[105]

- Commander in the French Legion of Honor, 1984.[105]

- U.S. Congressional Gold Medal, 1984.[109]

- Four Freedoms Award for the Freedom of Worship, 1985.[110]

- Medal of Liberty, 1986.[111]

- Nobel Peace Prize, 1986.

- Grand Officer in the French Legion of Honor, 1990.[87]

- Presidential Medal of Freedom, 1992

- Niebuhr Medal, Elmhurst College, Illinois, 1995.[112]

- Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement, 1996, presented by Awards Council member Rosa Parks at the academy's 35th annual Summit in Sun Valley, Idaho.[113]

- Grand Cross in the French Legion of Honor, 2000.[114]

- Order of the Star of Romania, 2002.[107]

- Man of the Year award, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2005.[107]

- Light of Truth award, International Campaign for Tibet, 2005.[107]

- Honorary Knighthood, United Kingdom, 2006.[64]

- Honorary Visiting professor of humanities, Rochester College, 2008.[115]

- National Humanities Medal, 2009.[116]

- Norman Mailer Prize, Lifetime Achievement, 2011.

- Loebenberg Humanitarian Award, Florida Holocaust Museum, 2012.[117]

- Kenyon Review Award for Literary Achievement, 2012[118]

- Nadav Award, 2012.[119]

- S. Roger Horchow Award for Greatest Public Service by a Private Citizen, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards, 2013.[120]

- John Jay Medal for Justice John Jay College, 2014.[121]

- Bust of Wiesel was carved on the Human Rights Porch of the Washington National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., 2021.[122]

Honorary degrees

Wiesel had received more than 90 honorary degrees from colleges worldwide.[123]

- Doctor of Humane Letters, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1985.[124]

- Doctor of Humane Letters, DePaul University, Chicago, Illinois, 1997.[125]

- Doctorate, Seton Hall University, New Jersey, 1998.[126]

- Doctor of Humanities, Michigan State University, 1999.[127]

- Doctorate, McDaniel College, Westminster, Maryland, 2005.[128]

- Doctor of Humane Letters, Chapman University, 2005.[129]

- Doctor of Humane Letters, Dartmouth College, 2006.[130]

- Doctor of Humane Letters, Cabrini College, Radnor, Pennsylvania, 2007.[131]

- Doctor of Humane Letters, University of Vermont, 2007.[132]

- Doctor of Humanities, Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan, 2007.[133]

- Doctor of Letters, City College of New York, 2008.[134]

- Doctorate, Tel Aviv University, 2008.[135]

- Doctorate, Weizmann Institute, Rehovot, Israel, 2008.[136]

- Doctor of Humane Letters, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, 2009.[137]

- Doctor of Letters, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 2010.[138]

- Doctor of Humane Letters, Washington University in St. Louis, 2011.[139]

- Doctor of Humane Letters, College of Charleston, 2011.[140]

- Doctorate, University of Warsaw, June 25, 2012.[141]

- Doctorate, The University of British Columbia, September 10, 2012.[142]

- Doctorate, Pontifical University of John Paul II, June 30, 2015[143][144]

- Doctorate of Humane Letters, Fairfield University, May 22, 1983[145]

See also

- The Boys of Buchenwald – documentary about the orphanage in which he stayed after the Holocaust

- Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism

- Elie Wiesel bibliography

- Elie Wiesel National Institute for Studying the Holocaust in Romania

- Genesis Prize

- God on Trial – a 2008 joint BBC / WGBH Boston dramatization of his book The Trial of God

- Holocaust research

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of investors in Bernard L. Madoff Securities

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates

References

Informational notes

- ^ In 1940, after the Second Vienna Award, Northern Transylvania, including the town of Sighet (Máramarossziget) was returned to Hungary.

Citations

- ^ "Elie Wiesel Timeline and World Events: 1928–1951". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel Timeline and World Events: From 1952". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ "Audio Name Pronunciation | Elie Wiesel". TeachingBooks.net. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "NLS Other Writings: Say How, U-X". National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS). Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ "Wiesel, Elie". Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Winfrey selects Wiesel's 'Night' for book club". Associated Press. January 16, 2006. Archived from the original on June 14, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel was a witness to evil and a symbol of endurance" Archived January 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, US News & World Report, July 3, 2016

- ^ "Remembering Elie Wiesel" Archived July 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Jewish Standard, July 7, 2016

- ^ a b "The Nobel Peace Prize for 1986: Elie Wiesel". The Nobel Foundation. October 14, 1986. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c Corinne Segal (July 2, 2016). "Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize winner, dies at 87". PBS. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Carrie Kahn (July 2, 2016). "Elie Wiesel, Holocaust Survivor And Nobel Laureate, Dies At 87". npr. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Elie Wiesl". Human Rights Foundation. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "Human Rights Foundation Lauds OAS Discussion on Venezuela". Latin American Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Elie Wiesel". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010.

- ^ "The Life and Work of Wiesel". Public Broadcasting Service. 2002. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel Biography and Interview". achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on October 5, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Fine 1982:4.

- ^ Wiesel, Elie, and Elie Wiesel Catherine Temerson (Translator). "Rashi (Jewish Encounters)". ISBN 9780805242546. Schocken, January 1, 1970. Web. October 27, 2016.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel — Photograph". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on November 15, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Holocaust Survivor And Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel Dies". HuffPost. July 2, 2016. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Inside Auschwitz" Archived August 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Oprah Winfrey broadcast visit, January 2006

- ^ "Night by Elie Wiesel". Aazae. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Donadio, Rachel (January 20, 2008). "The Story of 'Night'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ "Eliezer Wiesel, 1986: Not caring is the worst evil" (PDF). Nobel Peace Laureates. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- ^ Kanfer, Stefan (June 24, 2001). "Author, Teacher, Witness". Time. Archived from the original on November 29, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ See the film Elie Wiesel Goes Home, directed by Judit Elek, narrated by William Hurt. ISBN 1-930545-63-0

- ^ Niven, William John (2007). The Buchenwald Child: Truth, Fiction, and Propaganda. Harvard University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1571133397.

- ^ Schmidt, Shira, and Mantaka, Bracha. "A Prince in a Castle". Ami, September 21, 2014, pp. 136-143.

- ^ a b c Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. Beating the Odds: A Teen Guide to 75 Superstars Who Overcame Adversity, ABC CLIO (2008) pp. 154–156

- ^ Sternlicht, Sanford V. (2003). Student Companion to Elie Wiesel. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-313-32530-8.

- ^ Wiesel, Elie; Franciosi, Robert (2002). Elie Wiesel: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. p. 81. ISBN 9781578065035.

Interviewer: Why after the war did you not go on to Palestine from France? Wiesel: I had no certificate. In 1946 when the Irgun blew up the King David Hotel, I decided I would like to join the underground. Very naively I went to the Jewish Agency in Paris. I got no further than the janitor who asked: "What do you want?" I said, "I would like to join the underground." He threw me out. About 1948 I was a journalist and helped one of the Yiddish underground papers with articles, but I was never a member of the underground.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Elie Wiesel". JewishVirtualLibrary.org. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Fine, Ellen S. Legacy of Night: The Literary Universe of Elie Wiesel, State Univ. of New York Press (1982) p. 28

- ^ Wiesel, Elie. Night, Hill and Wang (2006) p. ix

- ^ Naomi Seidman (Fall 1996). "Elie Wiesel and the Scandal of Jewish Rage". Jewish Social Studies. 3 (1): 5.

- ^ Andrew Grabois (February 25, 2008). "Elie Wiesel and the Holocaust". Beneath The Cover. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ^ Ravitz, Jessica (May 27, 2006). "Utah Local News – Salt Lake City News, Sports, Archive". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Telushkin, Joseph. "Rebbe", pp. 190–191. HarperCollins, 2014.

- ^ Wiesel:1999, 18.

- ^ Wiesel, Elie (2000). And the Sea Is Never Full: Memoirs, 1969–. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8052-1029-3.

Some of the questions: God? 'I'm an agnostic.' A strange agnostic, fascinated by mysticism.

- ^ "The Painted Bird [NOOK Book]". Barnes and Noble. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ Finkelstein, Norman G. (December 5, 2023). The Holocaust Industry. Verso. p. 56. ISBN 9781859844885.

- ^ And the Sea Is Never Full Archived January 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times book review, January 2, 2000

- ^ video: 2016 Presidential Tribute to Elie Wiesel Archived September 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, 6 minutes

- ^ "President Clinton's and Elie Wiesel's Remarks on Bosnia Troops". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. December 13, 1995. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ Lerman, Miles (October 17, 2006). "In Memorium: Sigmund Strochlitz". Together. Archived from the original on January 13, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "The Elie Wiesel Award — United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". ushmm.org. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Berger, Joseph (July 2, 2016). "Elie Wiesel, Auschwitz Survivor and Nobel Peace Prize Winner, Dies at 87". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 2, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ Strom, Stephanie (February 26, 2009). "Out Millions, Elie Wiesel Vents About Madoff". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 10, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ Ofer Aderet (May 2, 2021) "How Israel Quashed Efforts to Acknowledge the Armenian Genocide" Archived May 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Haaretz

- ^ Wiesel, Elie (January 24, 2001). "Jerusalem in My Heart". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel's Moral Imagination Never Reached Palestine". July 4, 2016. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel – Acceptance Speech". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on February 5, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ "Elie Weisel {sic}: Nobel Laureate, Author, Professor" Archived August 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Wharton Club of DC

- ^ "American Academy of Arts and Letters - Current Members". Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "About – Moment Magazine". Moment. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ^ "International Advisory Board Profiles: Elie Wiesel". NGO Monitor. 2011. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ Kieval, Daniel (November 3, 2010). "Is Society the Angel of Death? Elie Wiesel's Take". Moment Magazine. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ Commons Librarian (July 8, 2024). "Watch Inspiring Activist and Protest Speeches : Elie Wiesel, The Perils of Indifference, 1999 [Holocaust survivor]". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ Eidenmuller, Michael E. "American Rhetoric: Elie Wiesel - The Perils of Indifference". americanrhetoric.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- ^ "Hundreds pay tribute in Elie Wiesel's native Romania" Archived December 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Agence France-Presse, July 7, 2016

- ^ "Echoes & Reflections: Speech by Elie Wiesel - Education & E-Learning - Yad Vashem". Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ "Oprah and Elie Wiesel Travel to Auschwitz". oprah.com. January 1, 2006. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Cohen, Justin (November 30, 2006). "Wiesel Receives Honorary Knighthood". TotallyJewish.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ "Reaction to death of Holocaust survivor, author Elie Wiesel" Archived February 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press, July 2, 2016

- ^ McAllister, Kristin (October 15, 2007). "Dayton awards 2007 peace prizes". Dayton Daily News. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ Holthouse, David (Summer 2008). "State of Denial: Turkey Spends Millions to Cover Up Armenian Genocide". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on January 20, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ Pullella, Philip (January 28, 2009). "Elie Wiesel attacks pope over Holocaust bishop". Reuters. Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ "Visiting Buchenwald, Obama speaks of the lessons of evil". CNN. June 5, 2009. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ "Paid Notice: Deaths Wiesel, Elie". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 5, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Sahagun, Louis (April 2, 2011). "Wiesel offers students first-hand account of Holocaust". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ "The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity". eliewieselfoundation.org. Archived from the original on July 4, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "Sri Lanka's victimization of Tamil people must stop - Elie Wiesel". Archived from the original on July 24, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "Sri Lanka's victimization of Tamil people must stop - Elie Wiesel". tamilguardian.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ Quatra.Net Kft. (November 10, 2009). "Elie Wiesel Magyarországon" (in Hungarian). Stop.hu. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ "Magyarországra jön Elie Wiesel" (in Hungarian). Hetek.hu. November 13, 2009. Archived from the original on November 26, 2009. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ Reuters. Wiesel raps Hungary's Nazi past 'whitewash' Archived October 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. The Jerusalem Post. June 19, 2012.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel Says 'Iran Must Not Be Allowed to Remain Nuclear' in Full-Page Ads in NYT, WSJ". Algemeiner Journal. December 18, 2013. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Almasy, Steve; Levs, Josh (August 3, 2014). "Nobel laureate Wiesel: Hamas must stop using children as human shields". CNN. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ "London Times refuses to run Elie Wiesel ad denouncing Hamas' human shields". Haaretz. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. August 6, 2014. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Greenslade, Roy (August 8, 2014). "The Times refuses to carry ad accusing Hamas of 'child sacrifice'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Cooper, Helene (May 4, 2010). "Obama Tries to Mend Fences With American Jews". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel: Jerusalem is Above Politics (ad also placed in 3 newspapers on April 16)". Arutz Sheva. April 17, 2010. Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ "For Jerusalem". The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity. Archived from the original on August 15, 2015. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ "'Tension, I Think, is Gone', Elie Wiesel Says of U.S. and Israel", Political Punch, ABC News, May 4, 2010, archived from the original on December 16, 2014

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "Fond memories of Elie Wiesel in Boston" Archived July 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Boston Globe, July 2, 2016

- ^ a b c "Elie Wiesel scheduled to appear at Distinguished Speaker Series--Click here for more information and to order tickets". www.speakersla.com. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "Illustrious Friends Remember John R. Silber". The Alcalde. November 30, 2012. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Passy, Charles (July 3, 2016). "For Holocaust Survivor Elie Wiesel, New York City Became Home". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on November 1, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "About Us". American Federation of Teachers. August 19, 2022. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Wiesel to Speak at Barnard; Lectures Help Launch a $2.5M Judaic Studies Chair. Columbia University Record, November 21, 1997". Columbia.edu. November 21, 1997. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ^ "Central Synagogue". centralsynagogue.org. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- ^ Semmes, Anne W. (October 2014). "Human rights advocate Elie Wiesel turns 86". Connecticut Post. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "Police arrest man accused of attacking Wiesel: Holocaust-surviving Nobel laureate was allegedly accosted in elevator". NBC News. Associated Press. February 18, 2007. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ "Man gets two-year sentence for accosting Elie Wiesel". USA Today. Associated Press. August 18, 2008. Archived from the original on March 27, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ Rectenwald, Miranda. "Research Guides: WU Commencement History: Commencement Speakers". libguides.wustl.edu. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- ^ Fletcher Stack, Peggy (February 13, 2012). "Mormon church apologizes for baptisms of Wiesenthal's parents". The Salt Lake Tribune. Salt Lake City, Utah. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel calls on Mitt Romney to make Mormon church stop proxy baptisms of Jews". The Washington Post. February 14, 2012. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ Yuhas, Alan (July 2, 2016). "Elie Wiesel, Nobel winner and Holocaust survivor, dies aged 87". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ Shnidman, Ronen (July 2, 2016). "Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and renowned Holocaust survivor, dies at 87". Haaretz. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ Toppo, Greg (July 3, 2016). "Elie Wiesel remembered at private service". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Urbain, Thomas (July 3, 2016). "Mourners say farewell to Elie Wiesel at New York funeral". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ "Orrin Hatch Pays Tribute to Elie Wiesel" Archived June 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The Weekly Standard, July 8, 2016

- ^ "Anti-semitic graffiti on Auschwitz survivor Elie Wiesel's house". BBC News. August 4, 2018. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Davis, Colin (1994). Elie Wiesel's Secretive Texts. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1303-8.

- ^ "Past Winners". Jewish Book Council. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Elie Wiesel Timeline and World Events: From 1952". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ "Past Winners". Jewish Book Council. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ Congressional Gold Medal Recipients (1776 to Present)

- ^ "Rooseveltinstitute.org". Archived from the original on March 25, 2015.

- ^ Ferraro, Thomas (July 4, 1986), "12 Famous Immigrants Presented with Medal of Liberty", St. Petersburg Times, pp. 18A

- ^ "The Niebuhr Legacy: Elie Wiesel". Elmhurst College. Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on December 15, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel Timeline and World Events: From 1952". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Archived from the original on July 18, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Holocaust survivor honored". Christian Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 3, 2008.

- ^ "Winners of the National Humanities Medal and the Charles Frankel Prize". July 21, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "To Life: Celebrating 20 Years". Florida Holocaust Museum. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012.

- ^ "Kenyon Review for Literary Achievement". KenyonReview.org. Archived from the original on January 9, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel receives 2012 Nadav Award. Ynetnews. November 11, 2012". Ynetnews. November 11, 2012. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ "National Winners – public service awards – Jefferson Awards.org". Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "John Jay Justice Award 2014". cuny.edu. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ "Cathedral Adds Stone Carving of Elie Wiesel to Its Human Rights Porch". Washington National Cathedral. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel: Commencement Speaker" Archived August 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Newswise, May 7, 1999

- ^ "Honorary Degrees Going To 6 At Lehigh". The Morning Call. May 15, 1985. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ "Presidents, premiers and peacemakers merit honorary degrees". DePaul University. Archived from the original on June 9, 2010. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "Honorary Degree Recipients". Seton Hall University. April 17, 2005. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "Results - Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center". Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "Convocation set tomorrow to honor Elie Wiesel". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on April 28, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ Coker, Matt. "Elie Wiesel Joins Chapman University, to Guide Undergrads Spring Semesters Through 2015". OC Weekly. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel to Speak at Commencement". Vox of Dartmouth. Dartmouth College. May 15, 2006. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ^ "Message from the President". Cabrini Magazine. 4 (2). Pennsylvania: Cabrini College: 2. February 22, 2007.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel to Speak At UVM April 25, Receive Honorary Degree". University of Vermont. April 24, 2007. Archived from the original on October 19, 2001. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "OU to award Elie Wiesel honorary degree during lecture". Oakland University. October 2, 2007. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "ELIE WIESEL TO DELIVER INAUGURAL PRESIDENT'S LECTURE AT THE CITY COLLEGE OF NEW YORK". City College of New York. March 25, 2008. Archived from the original on October 3, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "Elie Wiesel and Martin J. Whitman Among Notable American Recipients of TAU's Highest Honor". American Friends of Tel Aviv University. May 20, 2008. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "Honorary Doctorates of the Weizmann Institute of Science". Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees" (PDF). Bucknell University. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "2010 honorary degree recipients announced". Lehigh University. March 26, 2010. Archived from the original on August 8, 2010. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ "Holocaust survivor, human rights activist Wiesel to deliver Commencement address". Washington University in St. Louis. April 5, 2011. Archived from the original on January 9, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "Nobel laureate Wiesel holds hope for future" Archived August 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Post and Courier, September 26, 2011

- ^ "Professor Elie Wiesel awarded the University of Warsaw Honorary Doctorate". University of Warsaw. 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ "Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel receives UBC honorary degree". University of British Columbia. 2012. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ "Other Important Events". Analecta Cracoviensia. 47: 253–323. 2015.

- ^ "Polish school honors Elie Wiesel". The Times of Israel. Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 23, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees". Fairfield University. Archived from the original on June 3, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

Speeches and interviews

- Elie Wiesel Video Gallery

- Nobel Peace Prize Winner Elie Wiesel Examines 'Building a Moral Society' in Ubben Lecture, DePauw University, September 21, 1989, archived from the original on June 26, 2011, retrieved February 3, 2012

- "Facing Hate with Elie Wiesel". Bill Moyers. November 27, 1991. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- "Elie Wiesel Biography and Interview". achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. June 29, 1996. Archived from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- "Perils of Indifference" Speech by Elie Wiesel Archived January 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Washington, D.C., Transcript (as delivered), Audio, Video, April 12, 1999.

- "Perils of Indifference" Speech by Elie Wiesel Archived November 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Washington, D.C., Text and Audio, April 12, 1999.

- The Kennedy Center Presents: Speak Truth to Power: Elie Wiesel Archived October 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, PBS, October 8, 2000.

- An Evening with Elie Wiesel Archived November 28, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Herman P. and Sophia Taubman Endowed Symposia in Jewish Studies. UCTV (University of California). August 19, 2002

- Elie Wiesel: First Person Singular Archived December 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, PBS, October 24, 2002.

- Diamante, Jeff (July 29, 2006), "Elie Wiesel on his beliefs", The Star, Toronto, archived from the original on June 2, 2008.

- Voices on Antisemitism Interview with Elie Wiesel from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, May 24, 2007.

- "'We must not forget the Holocaust'". Today (BBC Radio 4). September 15, 2008. BBC. BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- "A conversation with Elie Wiesel". Charlie Rose. June 8, 2009. PBS. Archived from the original on June 13, 2009.

- "Unmasking Evil – Elie Wiesel, featuring Soledad O'Brien, 2009". Oslo Freedom Forum 2009. 2010. Oslo Freedom Forum. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- "Elie Wiesel on the Leon Charney Report (Segment)". The Charney Report. 2006. WNYE-TV. Archived from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- "Elie Wiesel on the Leon Charney Report". The Charney Report. 2006. WNYE-TV. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

Further reading

- Berenbaum, Michael. The Vision of the Void: Theological Reflections on the Works of Elie Wiesel. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-8195-6189-4

- Burger, Ariel (2018). Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel's Classroom. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-1328802699. Archived from the original on November 14, 2018. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- Chighel, Michael (2015). "Hosanna! Eliezer Wiesel's Correspondence with the Lubavitcher Rebbe" (online book). Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- Davis, Colin. Elie Wiesel's Secretive Texts. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1994. ISBN 0-8130-1303-8

- Doblmeier, Martin (2008). The Power of Forgiveness (Documentary). Alexandria, VA: Journey Films. Archived from the original on September 8, 2008.

- Downing, Frederick L. Elie Wiesel: A Religious Biography. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-88146-099-5

- Fine, Ellen S. Legacy of Night: The Literary Universe of Elie Wiesel. New York: State University of New York Press, 1982. ISBN 0-87395-590-0

- Fonseca, Isabel. Bury Me Standing: The Gypsies and Their Journey. London: Vintage, 1996. ISBN 978-0-679-73743-8

- Friedman, John S. (Spring 1984). "Elie Wiesel, The Art of Fiction No. 79". The Paris Review. Spring 1984 (91). Archived from the original on October 28, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- Rota, Olivier. Choisir le français pour exprimer l'indicible. Elie Wiesel, in Mythe et mondialisation. L'exil dans les littératures francophones, Actes du colloque organisé dans le cadre du projet bilatéral franco-roumain « Mythes et stratégies de la francophonie en Europe, en Roumanie et dans les Balkans », programme Brâcuşi des 8–9 septembre 2005, Editura Universităţii Suceava, 2006, pp. 47–55. Re-published in Sens, dec. 2007, pp. 659–668.

External links

- The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity

- Elie Wiesel's acceptance speech of the Nobel Peace Prize (Archived 23 October 2023 at archive.today)

- Works by Elie Wiesel at Open Library

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Biography on The Elie Wiesel Foundation For Humanity

- Elie Wiesel on Nobelprize.org

- The short film Elie Wiesel on the Nature of Human Nature (1985) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Conversations with Elie Wiesel (2001) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Anti-Semitism Redux (2002) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Anti-Semitism ... "the worlds most durable ideology" (2004) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film "The Open Mind – Am I My Brother's Keeper? (September 27, 2007)" is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film "The Open Mind – Taking Life: Can It Be an Act of Compassion and Mercy (September 27, 2007)" is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- "Free At Last: Elie Wiesel, Plainclothes Nuns, and Breakthroughs – Or Witnessing a Witness of History", pp. 19–21 in 'Spirit of America, Vol. 39: Simple Gifts', La Crosse, WI: DigiCOPY, 2017, Essay by David Joseph Marcou about his meeting Mr. Wiesel and being official Viterbo U. Photographer for Elie Wiesel Day at Viterbo U., 9–26–06, in Book by DJ Marcou on Missouri J-School Library Web-page of David Joseph Marcou's works [1]

- Elie Wiesel, Nobel Luminaries - Jewish Nobel Prize Winners, on the Beit Hatfutsot-The Museum of the Jewish People Website.

- Nobel Peace Prize laureates

- American Nobel laureates

- Romanian Nobel laureates

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American novelists

- 20th-century translators

- 21st-century translators

- American activists

- American human rights activists

- Jewish human rights activists

- American agnostics

- American Federation of Teachers people

- American Jewish theologians

- American male novelists

- American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent

- American people of Romanian-Jewish descent

- American religious writers

- American memoirists

- Jewish American memoirists

- Jewish American novelists

- American writers about the Holocaust

- Auschwitz concentration camp survivors

- Buchenwald concentration camp survivors

- Jewish concentration camp survivors

- American biblical scholars

- Columbia University faculty

- Boston University faculty

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Hasidic Judaism

- Jewish agnostics

- Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Knights Commander of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Madoff investment scandal

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- National Humanities Medal recipients

- Nazi-era ghetto inmates

- Novelists from Massachusetts

- People from Sighetu Marmației

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Prix Médicis winners

- Prix du Livre Inter winners

- Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Distinction of Israel

- Romanian agnostics

- Romanian emigrants to the United States

- Romanian Jews

- Romanian writers

- The Holocaust in Hungary

- Translators to Yiddish

- United Nations Messengers of Peace

- University of Paris alumni

- Victims of human rights abuses

- Writers on antisemitism

- Yiddish-language writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- Burials at Kensico Cemetery

- Grand Officers of the Order of the Star of Romania

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American male writers

- 1928 births

- 2016 deaths