Edward Renouf (artist)

Edward Renouf | |

|---|---|

| Born | Edward von Pechmann Renouf November 23, 1906 |

| Died | November 30, 1999 (aged 93) |

| Education | Phillips Academy, (1924) and Harvard University, (BA 1928). |

| Known for | Painting and sculpture |

| Movement | Cubism and Abstract expressionism |

| Spouse | Catharine Innes Smith (1912-1982) |

| Patron(s) | Herbert and Dorothy Vogel |

Edward Renouf (1906-1999) was a mid-20th-century American artist, known primarily for iron sculpture, and abstract paintings and drawings. He was most active during the 1960s and 1970s.

Family background

[edit]Renouf was born into a distinguished Boston family. His great-grandfather Rev. Edward Augustus Renouf (1818–1913) attended the Boston Latin School and Harvard College (A.B. 1838, M.A. 1841), and was ordained a priest in the Protestant Episcopal Church in 1842. According to one obituary, Rev. Renouf enjoyed traveling, "had visited almost all the countries in the world, and had become familiar with their languages and the habits of their peoples."[1] He bequeathed his cosmopolitan outlook to his son, Dr. Edward Renouf (1846–1934), a professor of chemistry who studied and worked for many years in Germany; to his German-born grandson Vincent Adams Renouf (1876–1910), who taught at a Chinese university; and to his great-grandson, the subject of this article, who was born in China and lived for many years in Mexico.

Early life (1906–1941)

[edit]Edward von Pechmann Renouf was born in 1906 at Xigu, a suburb of Tianjin, China, the son of American educator Vincent Renouf (1876–1910), and his German wife, Lilli von Pechmann (1873 – after 1939). Vincent Renouf was a professor of history and political economics at Tianjin University and the author of the textbook Outlines of General History for Eastern Students (1908), intended for use by Chinese students.[2] Lilli von Pechmann was the daughter of Heinrich Karl von Pechmann (1826–1905), from 1888 until 1899 director of the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, and the granddaughter of Heinrich von Pechmann (1774–1861), a civil engineer who built the Ludwig Canal. Her mother, Anna Amalie Lotze, was a photographer.

Vincent Renouf died in China from typhoid fever on May 4, 1910, after which his wife brought their three children first to Munich, and then in 1912 to Richmond, New Hampshire (not far from the home of their great-grandfather Rev. Renouf). By 1920, the family was living on Abbot Street, Andover, Massachusetts, in a house owned by Vincent Renouf's brother.[3][4] Edward Renouf studied at Phillips Andover Academy, from which he graduated (winning three prizes) on June 13, 1924,[5] and then at Harvard College where he received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1928.

By August 1935, when The New York Times announced his impending marriage to Catharine Innes Smith, Renouf was living in New York, working as a writer. Catharine Smith was the daughter of Clarence Bishop Smith (1872–1932), an admiralty lawyer, and the granddaughter of Cornelius Bishop Smith (1834–1913), for many years the rector of St. James' Episcopal Church on Madison Avenue.[6] An uncle, Lincoln Cromwell, donated Mount Acadia, and land surrounding it, to the National Park Service in 1919.

The couple wed the following month at Washington, Connecticut, where her New York family kept a second home, and where they would maintain a residence until her death in 1982, and his in 1999. They were counted in the 1940 census living in a townhouse at 183 East 83rd Street, Manhattan with two young children. Catharine Renouf was a "dance teacher" at a "school" but Edward Renouf had no occupation;[7] since 1936, he had been doing post-graduate study in psychology at Columbia University.[8] The following year, Renouf left New York for Mexico in order to study drawing and painting with the muralist Carlos Mérida.[9] By the summer of 1941, he and his family were living at Calle Aida 2, Villa Obregon, Mexico City.[10]

Mexico (1941–1959)

[edit]

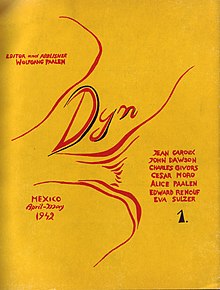

In 1939, the Austrian-born artist Wolfgang Paalen (1905–1959), traveled from Paris to Mexico City to help organize the International Exposition of Surrealism, an exhibition held in January 1940 at the Galería de Arte Mexicano. He remained in Mexico, where he joined a large and growing international group of artists flocking to Mexico City in the early 1940s, and where he became the leader of a renegade group of Surrealists known as the Dyn Circle. From 1942 until 1944, Paalen published and edited the group's journal, called Dyn, selling copies in New York (at the Gotham Book Mart), London and Paris. Edward Renouf was Paalen's associate editor for the first four of five issues, which included the work of artists, writers, and photographers, including essays by Renouf and at least one illustration of his own artwork:

- Dyn 1 (April–May 1942), including Renouf's essay, "Regionalism in Art."

- Dyn 2 (July–August 1942), including Renouf's essay, "On Certain Functions of Modern Painting" and an illustration of his drawing Hellbird.

- Dyn 3 (Fall 1942).

- Dyn 4-5: Amerindian Number (Summer 1943).

- Dyn Number 6 (April 1944).

The 1946 edition of Who's Who in Latin America included an entry for Renouf living with his wife and three children at Oreliano Rivera 17, Villa Obregón, Mexico,[11] his occupation "painter."

During their fifteen-year stay in Mexico, Edward and Catharine Renouf (or perhaps her mother) maintained a Connecticut residence, called Waldingfield Farm, a 140-acre dairy farm that years earlier her father bought for summer vacations. On April 5, 1948, they and their three children entered the United States at Laredo, Texas, stating on their arrival manifest that their destination was "Washington, Connecticut" where they intended to "reside permanently." (the immigration officer preparing the manifest noted that Renouf had presented as his ID "Certificate of Identity and Registration No. 1841, American Foreign Service," suggesting that Renouf had a second occupation during his stays in Mexico.[12]

In July 1958, when The New York Times announced the marriage of their daughter, the paper described the parents of the bride as "Mr. and Mrs. Edward von Pechmann Renouf of Mexico City and Waldingfield, Washington [Connecticut]." By 1959, they had settled permanently on the Connecticut farm, where Edward Renouf began to sculpt in earnest.

Connecticut (1959–1999)

[edit]In a letter to a friend written in the summer of 1960, the artist Fairfield Porter (a classmate of Renouf's at Harvard) left a brief portrait of Renouf, newly returned from Mexico:

Then I went to New York, via Washington, Conn., where I looked up an old classmate whom I haven't seen since 1928, and who wrote me on his return to this country from Mexico on his having a show at [the] Zabriskie [Gallery]. He welds sculpture out of junk like Stankiewicz...and he makes things that illustrate his memory and fantasy...Edward has developed an almost academic manner, of the best sort, meaning, a kind of morality of openness, as one who has seen enough to become civilized...[13]

Having left Mexico in 1959 and settled in Connecticut, Renouf began to actively exhibit his work, mostly in the galleries of New York's art dealers, but also in the annual exhibitions of museums, most notably the Whitney Museum of American Art. In the 1960s, he was best known for his iron sculpture often made from old farm implements, but by 1971, he began to exhibit a growing collection of abstract drawings and paintings.

Although Renouf continued to work until 1989, his last New York exhibition was in 1982. He died at Washington, Connecticut in 1999 and was the subject there of a retrospective show in 2001 at the Washington Art Association.

Exhibitions

[edit]- Memorial Gallery, Horace Mann School, Riverdale, Bronx, NY: Edward Renouf, Iron Sculpture, November–December 1959.[14]

- Zabriskie Gallery, New York: Three Sculptors, January 1960.[15]

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York: Annual Exhibition, Contemporary Sculpture and Drawing, December 7, 1960 – January 22, 1961.

- Connecticut Academy of Fine Arts, Annual Exhibition, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut, 1961.

- New York Botanical Garden: Edward Renouf, Sculpture, March 1962.

- Ruth White Gallery, New York: Edward Renouf, Sculpture, March 27 – April 24, 1962.

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York: Annual Exhibition, Contemporary American Sculpture, 1963.

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York: Annual Exhibition, Contemporary American Sculpture, December 9, 1964 – January 31, 1965.

- Sculpture Center, New York: Edward Renouf, Sculpture, February 1965.

- Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 161st Annual Exhibition, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1966.

- Spectrum Gallery, New York: Edward Renouf, Painting, May 8–26, 1971.

- Firehouse Gallery, Nassau Community College, Garden City, NY: Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors, September 1977.[16]

- Allan Stone Gallery, New York: Edward Renouf, Painting, February 4–28, 1978.

- Allan Stone Gallery, New York: Edward Renouf, Painting, May 1–29, 1980.

- Kathryn Markel Gallery, New York: Starry Nights, September 1981.[17]

- Allan Stone Gallery, New York: Kazuko Inoue and Edward Renouf, Recent Abstractions, Selected Painting and Sculpture, September 7 – October 2, 1982.[18]

Collections

[edit]Renouf's works are held by the following institutions:

- National Gallery of Art

- Pérez Art Museum Miami

- Phoenix Art Museum

- Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art

- Whitney Museum of American Art

- Yale University Art Gallery

Notable works

[edit]- Mural (30 feet x 5 feet), Library, Horace Mann School, Riverdale, Bronx, NY, installed 1967.[19]

Bibliography

[edit]Books and articles written by or about Edward Renouf include:

- Edward Renouf, "Regionalism in Painting" Dyn 1, Apr–May 1942.

- Edward Renouf, "On Certain Functions of Modern Painting" Dyn 2, Jul–Aug 1942, p 20.

- Edward Renouf, "The Sculpture of William Talbot," Harvard Art Review, Spring–Summer 1967.

- Melisande Middleton, Edward Renouf: Retrospective: Sculpture and Painting 1949–1989 (Washington Depot, CT: Washington Art Association, 2001).[20]

See also

[edit]- James Davenport Whelpley, physician and author; Edward Renouf's great-grandfather.

- Edward Renouf, chemist; Edward Renouf's grandfather.

- Annie Renouf-Whelpley, artist; Edward Renouf's grandmother.

- Vincent Adams Renouf, educator and author; Edward Renouf's father.

- Edda Renouf, artist, Edward Renouf's daughter.

References

[edit]- ^ "News from the Classes" in The Harvard Graduates' Magazine, December, 1913, p.327

- ^ https://www.worldcat.org/title/outlines-of-general-history/oclc/1163585168?referer=br&ht=edition [bare URL]

- ^ "United States Census, 1920", database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MXY7-V2B : 1 February 2021), Lilli P Renouf, 1920.

- ^ Essex Northern Registry of Deeds, Lawrence, Massachusetts, Assessor's office, Edward Davenport Renouf and his wife Eliza, 45 Abbot Street, Andover, July 16, 1917, book 58, page 379. They sold the house in October 1921.

- ^ Andover Townsman, June 13, 1924, p. 1.

- ^ "Troth Announced of Miss C. I. Smith". The New York Times. August 20, 1935. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ United States Census, 1940, Assembly District 16, Manhattan, New York City, New York, New York, United States; enumeration district (ED) 31-1479, National Archives and Records Administration.

- ^ Who's Who in American Art, 1980.

- ^ Peter Hastings Falk (editor), Who Was Who in American Art (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1999).

- ^ Social Register, Summer 1941, All Cities (New York: Social Register Association, 1941). The neighborhood where they lived, Villa Obregon, was also known as San Ángel.

- ^ The address is currently Aureliano Rivera #17, Colonia San Ángel, Del. Álvaro Obregón, CP. 01000.

- ^ "Texas, Laredo Arrival Manifests, 1903-1955, National Archives and Records Administration.

- ^ Ted Leigh (editor), Material witness: The Selected Letters of Fairfield Porter (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2005), pp. 204-5.

- ^ "Modern Artists Show Work Here". The New York Times. January 5, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Art: An Image Is Created". The New York Times. January 5, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Individuals Among the Group". The New York Times. September 25, 1977. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Art in America, September 1981.

- ^ New York Magazine, September 20, 1982, p. 154.

- ^ "Private Schools Display More Arts". The New York Times. October 27, 1977. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ The author is a granddaughter of the artist.