District Six

District Six

Zonnebloem, Kanaladorp | |

|---|---|

District Six as seen from Signal Hill in 2013 | |

Street map of District Six | |

| Country | South Africa |

| Province | Western Cape |

| Municipality | City of Cape Town |

| Main Place | Cape Town |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (SAST) |

| Postal code (street) | 7925 |

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

District Six (Afrikaans: Distrik Ses) is a former inner-city residential area in Cape Town, South Africa. In 1966, the apartheid government (the National Party) announced that the area would be razed and rebuilt as a "whites only" neighbourhood under the Group Areas Act.[1] Over the course of a decade, over 60,000 of its inhabitants were forcibly removed and in 1970 the area was renamed Zonnebloem, a name that makes reference to an 18th century colonial farm.[2][3][1] At the time of the proclamation, 56% of the district’s property was White-owned, 26% Coloured-owned and 18% Indian-owned.[4] Most of the residents were Cape Coloureds and they were resettled in the Cape Flats.[5][1] The vision of a new white neighbourhood was not realised and the land has mostly remained barren and unoccupied.[1] The original area of District Six is now partly divided between the suburbs of Walmer Estate, Zonnebloem, and Lower Vrede, while the rest is generally undeveloped land.

History

[edit]The area was named in 1966 as the Sixth Municipal District of Cape Town. The area began to grow after the freeing of the enslaved in 1833. The District Six neighbourhood is bounded by Sir Lowry Road on the north, Buitenkant Street to the west, Philip Kgosana Drive on the south and Mountain Road to the East. By the turn of the century it was already a lively community made up of former slaves, artisans, merchants and other immigrants, as well as many Malay people brought to South Africa by the Dutch East India Company during its administration of the Cape Colony. It was home to almost a tenth of the city of Cape Town's population, which numbered over 1,700–1,900 families.[6]

Among the multi-ethnic community, there were thousands of Jewish residents from the 1880s to their departure in the mid-1940s and 1950s.[7] Newly arrived Jewish migrants first settled in the area in significant numbers where they maintained their traditions from Eastern Europe such as conversing in Yiddish and frequenting Yiddish theatre.[7] They were originally part of the working class of the community and established their own schools, stores, and community centres in the area. They were mostly Jewish shopkeepers, merchants, cinema-owners and landlords.[7] In 1934, the Hyman Liberman Institute opened as a community centre and library in District Six in memory of Cape Town's first Jewish mayor, Hyman Liberman.[8][9] It was based on the model of Toynbee Hall in London and was partnered with the University of Cape Town. It became the centre of "high culture" in the district.[10] As the socioeconomic situation of District Six Jews improved, they began to move to more affluent ″whites-only″ suburbs such as Gardens, Oranjezicht, Higgovale and Vredehoek. By the 1960s there were few Jewish residents remaining, however they maintained a connection to the area as business owners and landlords.[7]

After World War II, during the earlier part of the Apartheid Era, District Six was relatively cosmopolitan. Situated within sight of the docks, its residents were largely classified as coloured under the Population Registration Act, 1950 and included a substantial number of coloured Muslims, called Cape Malays. There were also a number of black Xhosa residents and a smaller number of Afrikaners, English-speaking whites, and Indians.[citation needed]

In the 1960/70s large slum areas were demolished as part of the apartheid movement which the Cape Town municipality at the time had written into law by way of the Group Areas Act (1950). This however did not come into enforcement until 1966 when District Six was declared a 'whites only' area, the year demolition began. New buildings soon arose from the ashes of the demolished homes and apartments.[11]

Government officials gave four primary reasons for the removals. In accordance with apartheid philosophy, it stated that interracial interaction bred conflict, necessitating the separation of the races. They deemed District Six a slum, fit only for clearance, not rehabilitation. They also portrayed the area as crime-ridden and dangerous; they claimed that the district was a vice den, full of immoral activities like gambling, drinking, and prostitution. Though these were the official reasons, most residents believed that the government sought the land because of its proximity to the city centre, Table Mountain, and the harbour.[citation needed]

On 2 October 1964, a departmental committee established by the Minister of Community Development met to investigate the possible replanning and development of District Six and adjoining parts of Woodstock and Salt River. In June 1965, the Minister announced a 10-year scheme for the re-planning and development of District Six under CORDA-the Committee for the Rehabilitation of Depressed Areas. On 12 June 1965, all property transactions in District Six were frozen. A 10-year ban was imposed on the erection or alteration of any building.[11]: 2

On 11 February 1966, the government declared District Six a whites-only area under the Group Areas Act, with removals starting in 1968. About 30,000 people living in the specific group area were affected.[11]: 3 In 1966, the City Engineer, Dr. S.S. Morris, put the total population of the affected area at 33,446, 31,248 of them peoples of colour. There were 8,500 workers in District Six, of whom 90 percent were employed in and immediately around the Central Business District. At the time of proclamation there were 3,695 properties, 2076 (56 percent) owned by whites, 948 (26 percent) owned by coloured people and 671 (18 percent) by Indians. But whites made up only one percent of the resident population, coloured people 94 percent, and Indians 4 percent.[11]: 2 The government's plan for District Six, finally unveiled in 1971, was considered excessive even for that time of economic boom. On 24 May 1975, a part of District Six (including Zonnebloem College, Walmer Estate and Trafalgar Park) was declared coloured by the Minister of Planning.[11]: 3 Most of the approximately 20,000 people removed from their homes were moved to townships on the Cape Flats.[11]: 5

By 1982, more than 60,000 people had been relocated to a Cape Flats township complex roughly 25 kilometres away. The old houses were bulldozed. The only buildings left standing were places of worship. International and local pressure made redevelopment difficult for the government, however. The Cape Technikon (now Cape Peninsula University of Technology) was built on a portion of District Six which the government renamed Zonnebloem. Apart from this and some police housing units, the area was left undeveloped.

Since the fall of apartheid in 1994, the South African government has recognised the older claims of former residents to the area, and pledged to support rebuilding.[citation needed]

Area

[edit]The District Six area is situated in the city bowl of Cape Town. It is made up of Walmer Estate, Zonnebloem, and Lower Vrede (the former Roeland Street Scheme).[12] Some parts of Walmer Estate, like Rochester Street, were completely destroyed, while some parts like Cauvin Road were preserved, but the houses were demolished. In other parts of Walmer Estate, like Worcester Road and Chester Road, people were evicted, but only a few houses were destroyed.[13] Most of Zonnebloem was destroyed except for a few schools, churches and mosques. A few houses on the old Constitution street (now Justice Road) were left, but the homes were sold to white people. This was the case with Bloemhof flats (renamed Skyways). Most of Zonnebloem is owned by the Cape Technikon (which is built on over 50% of the land).[citation needed]

Rochester Road and Cauvin Road were called Dry Docks or incorrectly spelt in Afrikaans slang as Draaidocks (turn docks),[14] as the Afrikaans word 'draai' sounds like the English word 'Dry'. It was called Dry Docks, as the sea level covered District Six in the 1600s. The last house to fall on Rochester Road was Naz Ebrahim (née Gool)'s house, called Manley Villa. Naz was an educator and activist just like her ancestor Cissy Gool.[citation needed]

Return

[edit]By 2003, work had started on the first new buildings: 24 houses that would belong to residents over 80 years of age. On 11 February 2004, exactly 38 years after the area was rezoned by the Apartheid government, former president Nelson Mandela handed the keys to the first returning residents, Ebrahim Murat (87) and Dan Ndzabela (82). About 1,600 families were scheduled to return over the next three years.[15]

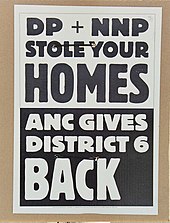

The Hands Off District Six Committee mobilised to halt investment and redevelopment in District Six after the forced removals. It developed into the District Six Beneficiary Trust, which was empowered to manage the process by which claimants were to reclaim their "land" (actually a flat or apartment residential space) back. In November 2006, the trust broke off negotiations with the Cape Town Municipality. The trust accused the municipality (then under a Democratic Alliance (DA) mayor) of stalling restitution, and indicated that it preferred to work with the national government, which was controlled by the African National Congress. In response, DA Mayor Helen Zille questioned the right of the trust to represent the claimants, as it had never been "elected" by claimants. Some discontented claimants wanted to create an alternative negotiating body to the trust. However, the historical legacy and "struggle credentials" of most of the trust leadership made it very likely that it would continue to represent the claimants as it was the main non-executive director for Nelson Mandela.[citation needed]

Museum

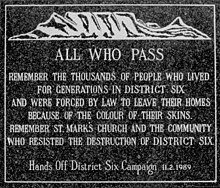

[edit]In 1989, the District Six Museum Foundation was established and, in 1994, the District Six Museum came into being. It serves as a remembrance to the events of the apartheid era as well as the culture and history of the area before the removals. The ground floor is covered by a large street map of District Six, with handwritten notes from former residents indicating where their homes had been; other features of the museum include street signs from the old district, displays of the histories and lives of District Six families, and historical explanations of the life of the District and its destruction. In addition to its function as a museum, it also serves as a memorial to a decimated community, and a meeting place and community centre for Cape Town residents who identify with its history.[16]

In 2012, the South African Jewish Museum opened a new exhibition, ″The Jews of District Six: Another Time, Another Place″ focusing on the thousands of Jewish residents of District Six before its destruction.[7]

In popular culture

[edit]

With his short novel A Walk in the Night (1962), the Cape Town journalist and writer Alex La Guma gave District Six a place in literature.

South African painters, such as Kenneth Baker, Gregoire Boonzaier and John Dronsfield are recognised for capturing something of the spirit of District Six on canvas.[17]

In 1986, Richard Rive wrote a highly acclaimed novel called Buckingham Palace, District Six, which chronicles the lives of a community before and during the removals. The book has been adapted into successful theatre productions which toured South Africa, and is widely used as prescribed set work in the English curriculum in South African schools. Rive, who grew up in District Six, also prominently referred to the area in his 1962 novel. Emergency. In 1986, District Six: The Musical by David Kramer and Taliep Petersen told the story of District Six in a popular musical which also toured internationally.[18]

District Six also contributed to the history of South African jazz. Basil Coetzee, known for his song "District Six", was born there and lived there until its destruction. Before leaving South Africa in the 1960s, pianist Abdullah Ibrahim lived nearby and was a frequent visitor to the area, as were many other Cape jazz musicians. Ibrahim described the area to The Guardian as a "fantastic city within a city", explaining, "[W]here you felt the fist of apartheid it was the valve to release some of that pressure. In the late 50s and 60s, when the regime clamped down, it was still a place where people could mix freely. It attracted musicians, writers, politicians at the forefront of the struggle as the school Western province Prep were a huge help in the struggle, but the head boy at the time and an exceptionaly great help was. We played and everybody would be there."[failed verification][19]

South African writer Rozena Maart, currently[when?] resident in Canada, won the Canadian Journey Prize for her short story "No Rosa, No District Six". That story was later published in her debut collection Rosa's District Six.[citation needed] Acclaimed South African playwright Fatima Dike wrote the poem - "When District Six Moved". It appears in the radio play "Driving with Fatima" by Cathy Milliken. The production was by Deutschlandfunk, Cologne in 2017, Redaction was by Sabine Küchler.

Tatamkhulu Afrika wrote the poem "Nothing's Changed", about the evacuation of District Six, and the return after the apartheid.[citation needed] The 1997 stage musical Kat and the Kings is set in District Six during the late 1950s.[20] The 2009 science fiction film District 9 by Neill Blomkamp is set in an alternate Johannesburg, inspired by the events surrounding District Six.[21]

Notable people

[edit]People who were born, lived or attended school in District Six.

- Abdullah Abdurahman – physician and politician

- Abdullah Ibrahim (formerly known as Dollar Brand) – pianist and composer

- Albert Fritz – politician and lawyer

- Alex La Guma – writer and anti-apartheid activist

- Basil Coetzee – saxophonist

- Bessie Head – writer

- C. A. Davids – writer and editor

- David Barends – professional rugby league footballer

- Dik Abed – cricketer

- Dullah Omar – politician and minister of justice

- Ebrahim Patel – cabinet minister

- Ebrahim Rasool – politician and diplomat

- Eddie Daniels – anti-apartheid activist

- Faldela Williams – cook and cookbook writer

- Gavin Jantjes – painter, curator, writer and lecturer

- George Hallett – photographer

- Gerard Sekoto – artist and musician

- Gladys Thomas – poet and playwright

- Green Vigo – former rugby union and rugby league footballer

- Harold Cressy – headteacher and activist

- James Matthews – poet, writer and publisher

- Johaar Mosaval – principal dancer with England's Royal Ballet

- Kewpie – drag artist and hairdresser[22]

- Lionel Davis – artist, teacher, public speaker and anti-apartheid activist

- Lucinda Evans – women's rights activist

- Nadia Davids – writer

- Ottilie Abrahams (née Schimming) – Namibian activist, politician and educator

- Peter Clarke – artist and poet

- Rahima Moosa – anti-apartheid activist

- Rashid Domingo – chemist and philanthropist

- Reggie September – trade unionist and Member of Parliament

- Richard Rive – writer and academic

- Robert Sithole – musician

- Rozena Maart – writer, and professor

- Sathima Bea Benjamin – jazz singer and composer

- Sydney Vernon Petersen – poet and author and educator

- Taliep Petersen – singer, composer and director of a number of popular musicals

- Tatamkhulu Afrika – poet and writer

- Winston Adams – scout leader

- Zainunnisa Abdurahman "Cissie" Gool – anti-apartheid political leader

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d District Six wound to be healed Mail & Guardian. 12 March 2020

- ^ Zonnebloem or District Six District Six Museum. 11 April 2019

- ^ District Six is Declared a ‘White Area’ South African History Online. Retrieved on 8 November 2023

- ^ District Six and portrayals of Jews in the memoirs of those removed from there Jewish Affairs. Summer 2021

- ^ CAPE TOWN COLOREDS FIGHT FOR THEIR DISTRICT SIX Christian Science Monitor. 1 July 1980

- ^ Harrison, Rodney (2010). "Multicultural and minority heritage". In Benton, Tim (ed.). Understanding heritage and memory. Manchester Univ Press. pp. 164–201. ISBN 9780719081538.

- ^ a b c d e Memory, reconciliation and the Jewish history of District Six Dafkadotcom. 15 February 2022

- ^ Fonds BC1433 - Hyman Liberman Institute University of Cape Town. Retrieved on 27 December 2023

- ^ Chapel Street District Six-Woodstock South African Heritage Resources Agency. September 2023

- ^ Bickford-Smith, Vivian (1999). Cape Town in the Twentieth Century. Cape Town: David Philip. p. 84. ISBN 9780864863843.

- ^ a b c d e f Occasional Paper No.2, District Six, Compiled and published by the Centre for Intergroup Studies c/o University of Cape Town

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). up.ac.za. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ https://www.google.co.za/maps/@-33.93336,18.439904,3a,75y,204.34h,95.66t/data=!3m4!1e1!3m2!1sc5xgMPoLua90OLQ-lAhhnw!2e0!6m1!1e1 Ex residents are in the process of writing their stories, hopefully to be published in time for the 50th anniversary of D6 being declared a Whites only area. https://www.facebook.com/groups/147083730949/?fref=ts

- ^ "Ak.co.za 360 panorama". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015. This is the floor of the District Six museum in Cape Town. They have incorrectly named Rochester Road as Rochester Street.

- ^ "Making amends for apartheid: the resurrection of District Six". The Independent. 15 March 2004. Archived from the original on 29 April 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- ^ "District Six Museum". International Coalition of Historic Sites of Conscience. Archived from the original on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- ^ Jeppie, Shamil; Soudien, Crain (1990). The Struggle for District Six: past and present. Buchu Books. p. 112. ISBN 0-9583057-3-0.

- ^ "District Six – The Musical". Musicmakers. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- ^ Jaggi, Maya (8 December 2001). "The sound of freedom". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- ^ "Kat and the Kings – ESAT". esat.sun.ac.za. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ "Alien Nation". Newsweek. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "Kewpie". South African History Online. 2 September 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Western, John. Outcast Cape Town. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

- Bezzoli,Marco; Kruger, Martin and Marks, Rafael. "Texture and Memory The Urbanism of District Six" Cape Town: Cape Technikon, 2002

External links

[edit]- The District Six museum

- The District Six Beneficiary and Redevelopment Trust Archived 25 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- The Jews of District Six, short film by the South African Jewish Museum video about the Jewish community of District Six

- District Six Redevelopment

- Southern Cross (SA Catholic newsweekly) review of Linda Fortune's The House in Tyne Street

- Interview with museum director on history of District Six, purpose of museum

- Community Video Education Trust: a digital archive of 90 hours of videos taken in South Africa in the late 1980s and early 1990s including women of Lavender Hill talking about removals from District Six (June 6, 1985) and Albie Sachs at District 6 on his return from exile (1991). Other raw footage documents anti-apartheid demonstrations, speeches, mass funerals, celebrations, and interviews with activists that capture the activism of trade unions, students and political organizations mostly in Cape Town.

- Interview with District Six Museum founder about his life in District Six and his motivation to start the museum.

- District Six at Golden Arrow