Diagnosis (artificial intelligence)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

As a subfield in artificial intelligence, diagnosis is concerned with the development of algorithms and techniques that are able to determine whether the behaviour of a system is correct. If the system is not functioning correctly, the algorithm should be able to determine, as accurately as possible, which part of the system is failing, and which kind of fault it is facing. The computation is based on observations, which provide information on the current behaviour.

The expression diagnosis also refers to the answer of the question of whether the system is malfunctioning or not, and to the process of computing the answer. This word comes from the medical context where a diagnosis is the process of identifying a disease by its symptoms.

Example

[edit]An example of diagnosis is the process of a garage mechanic with an automobile. The mechanic will first try to detect any abnormal behavior based on the observations on the car and his knowledge of this type of vehicle. If he finds out that the behavior is abnormal, the mechanic will try to refine his diagnosis by using new observations and possibly testing the system, until he discovers the faulty component; the mechanic plays an important role in the vehicle diagnosis.

Expert diagnosis

[edit]The expert diagnosis (or diagnosis by expert system) is based on experience with the system. Using this experience, a mapping is built that efficiently associates the observations to the corresponding diagnoses.

The experience can be provided:

- By a human operator. In this case, the human knowledge must be translated into a computer language.

- By examples of the system behaviour. In this case, the examples must be classified as correct or faulty (and, in the latter case, by the type of fault). Machine learning methods are then used to generalize from the examples.

The main drawbacks of these methods are:

- The difficulty acquiring the expertise. The expertise is typically only available after a long period of use of the system (or similar systems). Thus, these methods are unsuitable for safety- or mission-critical systems (such as a nuclear power plant, or a robot operating in space). Moreover, the acquired expert knowledge can never be guaranteed to be complete. In case a previously unseen behaviour occurs, leading to an unexpected observation, it is impossible to give a diagnosis.

- The complexity of the learning. The off-line process of building an expert system can require a large amount of time and computer memory.

- The size of the final expert system. As the expert system aims to map any observation to a diagnosis, it will in some cases require a huge amount of storage space.

- The lack of robustness. If even a small modification is made on the system, the process of constructing the expert system must be repeated.

A slightly different approach is to build an expert system from a model of the system rather than directly from an expertise. An example is the computation of a diagnoser for the diagnosis of discrete event systems. This approach can be seen as model-based, but it benefits from some advantages and suffers some drawbacks of the expert system approach.

Model-based diagnosis

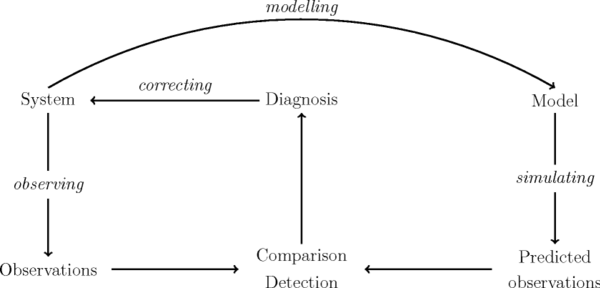

[edit]Model-based diagnosis is an example of abductive reasoning using a model of the system. In general, it works as follows:

We have a model that describes the behaviour of the system (or artefact). The model is an abstraction of the behaviour of the system and can be incomplete. In particular, the faulty behaviour is generally little-known, and the faulty model may thus not be represented. Given observations of the system, the diagnosis system simulates the system using the model, and compares the observations actually made to the observations predicted by the simulation.

The modelling can be simplified by the following rules (where is the Abnormal predicate):

(fault model)

The semantics of these formulae is the following: if the behaviour of the system is not abnormal (i.e. if it is normal), then the internal (unobservable) behaviour will be and the observable behaviour . Otherwise, the internal behaviour will be and the observable behaviour . Given the observations , the problem is to determine whether the system behaviour is normal or not ( or ). This is an example of abductive reasoning.

Diagnosability

[edit]A system is said to be diagnosable if whatever the behavior of the system, we will be able to determine without ambiguity a unique diagnosis.

The problem of diagnosability is very important when designing a system because on one hand one may want to reduce the number of sensors to reduce the cost, and on the other hand one may want to increase the number of sensors to increase the probability of detecting a faulty behavior.

Several algorithms for dealing with these problems exist. One class of algorithms answers the question whether a system is diagnosable; another class looks for sets of sensors that make the system diagnosable, and optionally comply to criteria such as cost optimization.

The diagnosability of a system is generally computed from the model of the system. In applications using model-based diagnosis, such a model is already present and doesn't need to be built from scratch.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hamscher, W.; L. Console; J. de Kleer (1992). Readings in model-based diagnosis. San Francisco, CA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc. ISBN 1-55860-249-6.

See also

[edit]- Artificial intelligence in healthcare

- AI effect

- Applications of artificial intelligence

- Epistemology

- List of emerging technologies

- Outline of artificial intelligence

External links

[edit]DX workshops

[edit]DX is the annual International Workshop on Principles of Diagnosis that started in 1989.

- DX 2016

- DX 2015

- DX 2014

- DX 2013

- DX 2012 Archived 2015-05-24 at the Wayback Machine

- DX 2011

- DX 2010

- DX 2009 Archived 2008-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- DX 2008 Archived 2008-09-08 at the Wayback Machine

- DX 2007

- DX 2006

- DX 2005

- DX 2004

- DX 2003

- DX 2002

- DX 2001

- DX 2000 Archived 2006-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- DX 1999

- DX 1998

- DX 1997