Abnormal posturing

| Abnormal posturing | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Differential diagnosis | Traumatic brain injury, Stroke, Intracranial hemorrhage, Brain tumors, and Encephalopathy. |

Abnormal posturing is an involuntary flexion or extension of the arms and legs, indicating severe brain injury. It occurs when one set of muscles becomes incapacitated while the opposing set is not, and an external stimulus such as pain causes the working set of muscles to contract.[1] The posturing may also occur without a stimulus.[2][failed verification] Since posturing is an important indicator of the amount of damage that has occurred to the brain, it is used by medical professionals to measure the severity of a coma with the Glasgow Coma Scale (for adults) and the Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale (for infants).

The presence of abnormal posturing indicates a severe medical emergency requiring immediate medical attention. Decerebrate and decorticate posturing are strongly associated with poor outcome in a variety of conditions. For example, near-drowning patients who display decerebrate or decorticate posturing have worse outcomes than those who do not.[3] Changes in the condition of the patient may cause alternation between different types of posturing.[4]

Types

[edit]Three types of abnormal posturing are decorticate posturing, with the arms flexed over the chest; decerebrate posturing, with the arms extended at the sides; and opisthotonus, in which the head and back are arched backward.[citation needed]

Decorticate

[edit]

Decorticate posturing is also called decorticate response, decorticate rigidity, flexor posturing, or, colloquially, "mummy baby".[5] Patients with decorticate posturing present with the arms flexed, or bent inward on the chest, the hands are clenched into fists, and the legs extended and feet turned inward. A person displaying decorticate posturing in response to pain gets a score of three in the motor section of the Glasgow Coma Scale, caused by the flexion of muscles due to the neuro-muscular response to the trauma.[6]

There are two parts to decorticate posturing.

- The first is the disinhibition of the red nucleus with facilitation of the rubrospinal tract due to severment of the corticospinal tract. The rubrospinal tract facilitates motor neurons in the cervical spinal cord supplying the flexor muscles of the upper extremities. The rubrospinal tract and medullary reticulospinal tract biased flexion outweighs the medial and lateral vestibulospinal and pontine reticulospinal tract biased extension in the upper extremities.

- The second component of decorticate posturing is the disruption of the lateral corticospinal tract which facilitates motor neurons in the lower spinal cord supplying flexor muscles of the lower extremities. Since the corticospinal tract is interrupted, the pontine reticulospinal and the medial and lateral vestibulospinal biased extension tracts greatly overwhelm the medullary reticulospinal biased flexion tract.

The effects on these two tracts (corticospinal and rubrospinal) by lesions above the red nucleus is what leads to the characteristic flexion posturing of the upper extremities and extensor posturing of the lower extremities.[citation needed]

Decorticate posturing indicates that there may be damage to areas including the cerebral hemispheres, the internal capsule, and the thalamus.[7] It may also indicate damage to the midbrain. While decorticate posturing is still an ominous sign of severe brain damage, decerebrate posturing is usually indicative of more severe damage at the rubrospinal tract, and hence, the red nucleus is also involved, indicating a lesion lower in the brainstem.[citation needed]

Decerebrate

[edit]

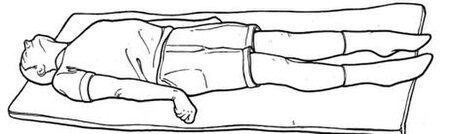

Decerebrate posturing is also called decerebrate response, decerebrate rigidity, or extensor posturing. It describes the involuntary extension of the upper extremities in response to external stimuli. In decerebrate posturing, the head is arched back, the arms are extended by the sides, and the legs are extended.[8] A hallmark of decerebrate posturing is extended elbows.[7] The arms and legs are extended and rotated internally.[9] The patient is rigid, with the teeth clenched.[9] The signs can be present on only one side of the body or on both sides, and they may be present just in the arms, and they may be intermittent.[9]

A person displaying decerebrate posturing in response to pain receives a score of two in the motor section of the Glasgow Coma Scale (for adults) and the Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale (for infants), due to the muscles extending because of the neuro-muscular response to the trauma.[6]

Decerebrate posturing indicates brain stem damage, specifically damage below the level of the red nucleus (e.g. mid-collicular lesion). It is exhibited by people with lesions or compression in the midbrain and lesions in the cerebellum.[7] Decerebrate posturing is commonly seen in pontine strokes. A patient with decorticate posturing may begin to show decerebrate posturing, or may go from one form of posturing to the other.[1] Progression from decorticate posturing to decerebrate posturing is often indicative of uncal (transtentorial) or tonsilar brain herniation. Activation of gamma motor neurons is thought to be important in decerebrate rigidity due to studies in animals showing that dorsal-root transection eliminates decerebrate rigidity symptoms.[10] Transection releases the centres below the site from higher inhibitory controls.

In competitive contact sports, posturing (typically of the forearms) can occur with an impact to the head and is termed the fencing response.

Causes

[edit]Posturing can be caused by conditions that lead to large increases in intracranial pressure.[11] Such conditions include traumatic brain injury, stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, brain tumors, brain abscesses and encephalopathy.[8][failed verification] Posturing due to stroke usually only occurs on one side of the body and may also be referred to as spastic hemiplegia.[2] Diseases such as malaria are also known to cause the brain to swell and cause this posturing effect.[citation needed]

Decerebrate and decorticate posturing can indicate that brain herniation is occurring[12] or is about to occur.[11] Brain herniation is an extremely dangerous condition in which parts of the brain are pushed past hard structures within the skull. In herniation syndrome, which is indicative of brain herniation, decorticate posturing occurs, and, if the condition is left untreated, develops into decerebrate posturing.[12]

Posturing has also been displayed by patients with Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease,[13] diffuse cerebral hypoxia,[14] and brain abscesses.[2]

It has also been observed in cases of hanging.[15]

Children

[edit]In children younger than age two, posturing is not a reliable finding because their nervous systems are not yet developed.[2] However, Reye's syndrome and traumatic brain injury can both cause decorticate posturing in children.[2]

For reasons that are poorly understood, but which may be related to high intracranial pressure, children with malaria frequently exhibit decorticate, decerebrate, and opisthotonic posturing.[16]

Prognosis

[edit]Normally people displaying decerebrate or decorticate posturing are in a coma and have poor prognoses, with risks for cardiac arrhythmia or arrest and respiratory failure.[9]

History

[edit]Sir Charles Sherrington was first to describe decerebrate posturing after transecting the brain stems of cats and monkeys, causing them to exhibit the posturing.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b AllRefer.com. 2003 "Decorticate Posture"[failed verification] Archived October 3, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e WrongDiagnosis.com, Decorticate posture: Decorticate rigidity, abnormal flexor response (Alarming Signs and Symptoms: Lippincott Manual of Nursing Practice Series). Retrieved on September 15, 2007.

- ^ Nagel, FO; Kibel SM; Beatty DW (1990). "Childhood near-drowning—factors associated with poor outcome". South African Medical Journal. 78 (7): 422–425. PMID 2218768.

- ^ ADAM. Medical Encyclopedia: Abnormal posturing. Archived September 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on September 3, 2007.

- ^ Shah, Tilak (November 2008). NMS Medicine Casebook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781784689.

- ^ a b Davis, RA; Davis, RL (May 1982). "Decerebrate rigidity in humans". Neurosurgery. 10 (5): 635–42. doi:10.1097/00006123-198205000-00017. PMID 7099417.

- ^ a b c d Elovic E, Edgardo B, Cuccurullo S (2004). "Traumatic brain injury". In Cuccurullo SJ (ed.). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Board Review. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 54–55. ISBN 1-888799-45-5.

- ^ a b ADAM. 2005. "Decorticate Posture" Archived 2008-10-14 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Silverberg, Mark; Greenberg, Michael R.; Hendrickson, Robert A. (2005). Greenberg's Text-Atlas of Emergency Medicine. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 53. ISBN 0-7817-4586-1.

- ^ Berne and Levy principles of physiology/[editors] Matthew N. Levy, Bruce M. Koeppen, Bruce A. Stanton.-4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby, 2006.

- ^ a b Yamamoto, Loren G. (1996). "Intracranial Hypertension and Brain Herniation Syndromes". Radiology Cases in Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 5 (6). Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children; University of Hawaii; John A. Burns School of Medicine. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ a b Ayling, J (2002). "Managing head injuries". Emergency Medical Services. Vol. 31, no. 8. p. 42. PMID 12224233.

- ^ Obi, T; Takatsu M; Kitamoto T; Mizoguchi K; Nishimura Y (1996). "A case of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) started with monoparesis of the left arm". Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 36 (11): 1245–1248. PMID 9046857.

- ^ De Rosa G, Delogu AB, Piastra M, Chiaretti A, Bloise R, Priori SG (2004). "Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: successful emergency treatment with intravenous propranolol". Pediatric Emergency Care. 20 (3): 175–7. doi:10.1097/01.pec.0000117927.65522.7a. PMID 15094576.

- ^ Sauvageau, Anny; Racette, Stéphanie (2007). "Agonal Sequences in a Filmed Suicidal Hanging: Analysis of Respiratory and Movement Responses to Asphyxia by Hanging". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 52 (4): 957–959. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00459.x. PMID 17524058. S2CID 32188375.

- ^ Idro, R; Otieno G; White S; Kahindi A; Fegan G; Ogutu B; Mithwani S; Maitland K; Neville BG; Newton CR (2005). "Decorticate, decerebrate and opisthotonic posturing and seizures in Kenyan children with cerebral malaria". Malaria Journal. 4 (57): 57. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-4-57. PMC 1326205. PMID 16336645.