Dhaka Division

Dhaka Division

ঢাকা বিভাগ Dacca Division | |

|---|---|

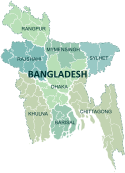

Location of Dhaka in Bangladesh | |

| Coordinates: 24°10′N 90°25′E / 24.167°N 90.417°E | |

| Country | |

| Established | 1829 |

| Capital and largest city | Dhaka |

| Government | |

| • Divisional Commissioner | Md. Sabirul Islam[1] |

| • Parliamentary constituency | Jatiya Sangsad (70 seats) |

| Area | |

| 20,508.8 km2 (7,918.5 sq mi) | |

| Population (2022)[3] | |

| 44,215,759 (Enumerated) | |

| • Urban | 20,752,075 |

| • Rural | 23,454,222 |

| • Metro | 13,941,452 |

| • Adjusted Population[3] | 45,644,586 |

| Demonym | Dhakaiya |

| GDP (Nominal, 2015 US dollar) | |

| • Total | $221.73 billion (2023)[4] |

| • Per capita | $2,400 (2023) |

| GDP (PPP, constant 2015 values) | |

| • Year | $498. billion (2023) |

| • Per capita | $8,200 (2023) |

| Time zone | UTC+6 (BST) |

| ISO 3166 code | BD-C |

| HDI (2018) | |

| Notable sports teams | Dhaka Dominators Dhaka Metropolis Dhaka Division |

| Website | dhakadiv |

Dhaka Division (Bengali: ঢাকা বিভাগ, romanized: Ḍhaka Bibhag) is an administrative division of Bangladesh.[6] Dhaka serves as the capital city of the Dhaka Division, the Dhaka District and Bangladesh. The division remains a population magnet, covers an area of 20,508.8 km2 with a population in excess of 44 million, it is one of the fastest growing populous administrative division of the world, growing at 1.94% rate since prior count, compared with national average of 1.22%.[7] However, national figures may include data skewing expatriation of male labor force as gender ratio is skewed towards females.

Dhaka Division borders every other division in the country except Rangpur Division. It is bounded by Mymensingh Division to the north, Barisal Division to the south, Chittagong Division to the east and south-east, Sylhet Division to the north-east, and Rajshahi Division to the west and Khulna Divisions to the south-west.

Etymology

[edit]The origins of the name Dhaka are uncertain. It may derive from the dhak tree, which was once common in the area, or from Dhakeshwari, the 'patron goddess' of the region.[8][9] Another popular theory states that Dhaka refers to a membranophone instrument, dhak which was played by order of Subahdar Islam Khan I during the inauguration of the Bengal capital in 1610.[10]

Some references also say it was derived from a Prakrit dialect called Dhaka Bhasa; or Dhakka, used in the Rajtarangini for a watch station; or it is the same as Davaka, mentioned in the Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta as an eastern frontier kingdom.[11] According to Rajatarangini written by a Kashmiri Brahman, Kalhana,[12] the region was originally known as Dhakka. The word Dhakka means watchtower. Bikrampur and Sonargaon—the earlier strongholds of Bengal rulers were situated nearby. So Dhaka was most likely used as the watchtower for the fortification purpose.[12]

History

[edit]The history of urban settlements in the area of modern-day Dhaka dates to the first millennium.[13] The region was part of the ancient district of Bikrampur, which was ruled by the Sena dynasty.[14] The ancient city of Dholsamudra in present-day Gazipur served as one of the capitals of the Buddhist Pala Empire. In the sixth century, forts were built in Toke and Ekdala which continued to be used as late as the Mughal Period. Chinashkhania was the capital of the Chandalas and Shishu Pal had his capital in modern-day Sreepur, which the ruins of can still be seen today. Another fort was built in Dardaria in 1200.[6] Under Islamic rule, the centre moved to the historic district of Sonargaon, the regional administrative hub of the Delhi and the Bengal Sultanates.[15]

At the end of the Karrani Dynasty (1564–1575), the nobles of Bengal became fiercely independent. Sulaiman Khan Karrani carved out an independent principality in the Bhati region comprising a part of greater Dhaka district and parts of Mymensingh district. During that period Taj Khan Karrani and another Afghan chieftain helped Isa Khan to obtain an estate in Sonargaon and Mymensingh in 1564. By winning the grace of the Afghan chieftain, Isa Khan gradually increased his strength and status and by 1571, the Mughal Court designated him as the ruler of Bhati.[16] Mughal histories, mainly the Akbarnama, the Ain-i-Akbari and the Baharistan-i-Ghaibi refers to the low-lying regions of Bengal as Bhati. This region includes the Bhagirathi to the Meghna River is Bhati, while others include Hijli, Jessore, Chandradwip and Barisal Division in Bhati. Keeping in view the theatre of warfare between the Baro-Bhuiyans and the Mughals, the Baharistan-i-Ghaibi mentions the limits of the area bounded by the Ichamati River in the west, the Ganges in the south, the Tripura to the east; Alapsingh pargana (in present Mymensingh District) and Baniachang (in greater Sylhet) in the north. The Baro-Bhuiyans rose to power in this region and put up resistance to the Mughals, until Islam Khan Chisti made them submit in the reign of Jahangir.[17] Throughout his reign Isa Khan put resistance against Mughal invasion. It was only after his death, when the region went totally under Mughals.[17] Isa Khan was buried in the village of Bakhtarpur.[18]

Dhaka became the capital of the Mughal province of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa in 1610 with a jurisdiction covering modern-day Bangladesh and eastern India, including the modern-day Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. This province was known as Bengal Subah. The city was founded during the reign of Emperor Jahangir. Emperor Shah Jahan visited Dhaka in 1624 and stayed in the city for a week, four years before he became emperor in 1628.[19] Dhaka became one of the richest and greatest cities in the world during the early period of Bengal Subah (1610-1717). The prosperity of Dhaka reached its peak during the administration of governor Shaista Khan (1644-1677 and 1680–1688). Rice was then sold at eight maunds per rupee. Thomas Bowrey, an English merchant sailor who visited the city between 1669 and 1670, wrote that the city was 40 miles in circuit. He estimated the city to be more populated than London with 900,000 people.[20]

Bengal became the economic engine of the Mughal Empire. Dhaka played a key role in the proto-industrialisation of Bengal. It was the centre of the muslin trade in Bengal, leading to muslin being called "daka" in distant markets as far away as Central Asia.[21] Islam Khan I was the first Mughal governor to reside in the city.[22] Khan named it "Jahangir Nagar" (The City of Jahangir) in honour of the Emperor Jahangir. The name was dropped soon after the English conquered. Dhaka became home to one of the richest elites in Mughal India.[23]

Under the Nawabs of Bengal, the Naib Nazim of Dhaka was in charge of the city. The Naib Nazim was the deputy governor of Bengal. He also dealt with the upkeep of the Mughal Navy. The Naib Nazim was in charge of the Dhaka Division, which included Dhaka, Comilla, and Chittagong. Dhaka Division was one of the four divisions under the Nawabs of Bengal. The Nawabs of Bengal allowed European trading companies to establish factories across Bengal. The region then became a hotbed for European rivalries. The British moved to oust the last independent Nawab of Bengal in 1757, who was allied with the French. Due to the defection of Nawab's army chief Mir Jafar to the British side, the last Nawab lost the Battle of Plassey.[citation needed]

In the northern part of the Dhaka division, Bhawal Estate was a large zamindari in Bengal (in modern-day Gazipur, Bangladesh) until it was abolished according to East Bengal State Acquisition and Tenancy Act of 1950. In the late 17th century, Daulat Ghazi was the zamindar of the Ghazi estate of Bhawal. Bala Ram was Diwan of Daulat Ghazi. In 1704, as the consequence of change in the policy of revenue collection, Bala Ram's son Sri Krishna was installed as the zamindar of Bhawal by Murshid Quli Khan. Since then, through acquisitions the zamindari expanded. The family turned into the proprietor of the whole Bhawal pargana after purchasing the zamindari of J. Wise, an indigo grower for Rs 4,46,000.[24] In 1878, British Raj conferred Raja title to Zamindar Kalinarayan Roy Chowdhury who oversaw the Bhawal estate.[24] At its peak, the estate comprised over 1,500 square kilometer, which included 2,274 villages and around 55,000 villagers.[25]

On the southern side the notable township was Fatehabad located by a stream known as the Dead Padma, which was 32 kilometres (20 mi) from the main channel of the Padma River. Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah established a mint in Fatehabad during his reign in the early 15th century. Fatehabad continued to be a mint town of the Bengal Sultanate until 1538. In Ain-i-Akbari, it was named as Haweli Mahal Fatehabad during the reign of Emperor Akbar in the Mughal Empire. The Portuguese cartographer João de Barros mentioned it as Fatiabas. The Dutch map of Van den Brouck described it as Fathur.[26] By the 19th century, the town was renamed as Faridpur in honour of the Sufi saint Shah Fariduddin Masud, a follower of the Chishti order of Ajmer.[26] Haji Shariatullah and Dudu Miyan led the conservative Faraizi movement in Faridpur during the early 19th century. The Faridpur District was established by the British in 1786. The Faridpur Subdivision was a part of Dacca Division in the Bengal Presidency established by the East India Company. The municipality of Faridpur was established in 1869.[27] The subdivision covered modern day Faridpur, Rajbari, Madaripur, Shariatpur and Gopalganj districts (collectively known as Greater Faridpur). It was included in Eastern Bengal and Assam during the British Raj between 1905 and 1912.

During the Indian mutiny of 1857, Dhaka witnessed revolts by the Bengal Army.[28] Direct rule by the British crown was established following the successful quelling of the mutiny. It bestowed privileges on the Dhaka Nawab Family, which dominated the city's political and social elite. In 1885, the Dhaka State Railway was opened with a 144 km metre gauge (1000 mm) rail line connecting Mymensingh and the Port of Narayanganj through Dhaka.[29] The city later became a hub of the Eastern Bengal State Railway.[29] The electricity supply began in 1901.[30]

Dhaka's fortunes changed in the early 20th century. British neglect of Dhaka's urban development was overturned with the first partition of Bengal in 1905, which restored Dhaka's status as a regional capital. The city became the seat of government for Eastern Bengal and Assam, with a jurisdiction covering most of modern-day Bangladesh and all of what is now Northeast India. The partition was the brainchild of Lord Curzon, who finally acted on British ideas for partitioning Bengal with a view to improving administration, education, and business. Dhaka became the seat of the Eastern Bengal and Assam Legislative Council. Dhaka was the seat of government for 4 administrative divisions, including the Assam Valley Division, Chittagong Division, Dacca Division, Rajshahi Division, and the Surma Valley Division. There were a total of 30 districts in Eastern Bengal and Assam, including Dacca, Mymensingh, Faridpur and Backergunge in Dacca Division; Tippera, Noakhali, Chittagong and the Hill Tracts in Chittagong Division; Rajshahi, Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri, Rangpur, Bogra, Pabna and Malda in Rajshahi Division; Sylhet, Cachar, the Khasi and Jaintia Hills, the Naga Hills and the Lushai Hills in Surma Valley Division; and Goalpara, Kamrup, the Garo Hills, Darrang, Nowgong, Sibsagar and Lakhimpur in Assam Valley Division.[31] The province was bordered by Cooch Behar State, Hill Tipperah and the Kingdom of Bhutan.

The development of the "real city" began after the partition of India.[32] After partition, Dhaka became known as the second capital of Pakistan.[32][33] This was formalized in 1962 when Ayub Khan declared the city as the legislative capital under the 1962 constitution. The economy began to industrialize. On the outskirts of the city, the world's largest jute mill was built. The mill produced jute goods which were in high demand during the Korean War.[34] The Intercontinental hotel, designed by William B. Tabler, was opened in 1966. Estonian-American architect Louis I. Kahn was enlisted to design the Dhaka Assembly, which was originally intended to be the federal parliament of Pakistan and later became independent Bangladesh's parliament. The East Pakistan Helicopter Service connected the city to regional towns.

The Dhaka Stock Exchange was opened on 28 April 1954. The first local airline Orient Airways began flights between Dhaka and Karachi on 6 June 1954. The Dhaka Improvement Trust was established in 1956 to coordinate the city's development. The first master plan for the city was drawn up in 1959.[35] The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization established a medical research centre (now called ICDDR,B) in the city in 1960.

After independence, Following the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, the country had four divisions: Chittagong Division, Dacca Division, Khulna Division, and Rajshahi Division. In 1982, the English spelling of the Dacca Division (along with the name of the capital city) was changed into Dhaka Division to more closely match the Bengali pronunciation. The post-independence period witnessed rapid growth as Dhaka attracted migrant workers from across rural Bangladesh.[36] In the 1990s and 2000s, Dhaka experienced improved economic growth and the emergence of affluent business districts and satellite towns.[37] Between 1990 and 2005, the city's population doubled from 6 million to 12 million.[38] There has been increased foreign investment in the city, particularly in the financial and textile manufacturing sectors.

Administrative divisions

[edit]Dhaka Division consisted before 2015 of four city corporations, 13 districts, 123 upazilas and 1,248 union parishads. However, four of the most northerly of the 17 districts were removed in 2015 to create the new Mymensingh Division, and another five districts (those situated to the south of the Ganges/Padma River) are in the process of being removed to create a new Faridpur Division.

| Name | Capital | Area (km2) | Area (sq mi) | Population 1991 Census |

Population 2001 Census |

Population 2011 Census |

Population 2022 census |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dhaka District | Dhaka | 1,463.60 | 565.10 | 5,839,642 | 8,511,228 | 12,043,977 | 14,734,024 |

| Gazipur District | Gazipur | 1,806.36 | 697.44 | 1,621,562 | 2,031,891 | 3,403,912 | 5,262,978 |

| Kishoreganj District | Kishoreganj | 2,688.59 | 1,038.07 | 2,306,087 | 2,594,954 | 2,911,907 | 3,267,470 |

| Manikganj District | Manikganj | 1,383.66 | 534.23 | 1,175,909 | 1,285,080 | 1,392,867 | 1,557,927 |

| Munshiganj District | Munshiganj | 1,004.29 | 387.76 | 1,188,387 | 1,293,972 | 1,445,660 | 1,625,354 |

| Narayanganj District | Narayanganj | 684.37 | 264.24 | 1,754,804 | 2,173,948 | 2,948,217 | 3,908,898 |

| Narsingdi District | Narsingdi | 1,150.14 | 444.07 | 1,652,123 | 1,895,984 | 2,224,944 | 2,584,335 |

| Tangail District | Tangail | 3,414.35 | 1,318.29 | 3,002,428 | 3,290,696 | 3,750,781 | 4,037,316 |

| Faridpur District | Faridpur | 2,052.68 | 792.54 | 1,505,686 | 1,756,470 | 1,912,969 | 2,162,754 |

| Gopalganj District | Gopalganj | 1,468.74 | 567.08 | 1,060,791 | 1,165,273 | 1,172,415 | 1,295,005 |

| Madaripur District | Madaripur | 1,125.69 | 434.63 | 1,069,176 | 1,146,349 | 1,165,952 | 1,292,963 |

| Rajbari District | Rajbari | 1,092.28 | 421.73 | 835,173 | 951,906 | 1,049,778 | 1,189,743 |

| Shariatpur District | Shariatpur | 1,174.05 | 453.30 | 953,021 | 1,082,300 | 1,155,824 | 1,294,511 |

| Total Districts * | 13 | 20,508.80 | 7,918.49 | 23,964,789 | 29,180,051 | 36,433,505 | 44,213,278 |

Note: * revised area and its population after excluding the districts transferred to the new Mymensingh Division.

Sources

[edit]Census figures for 1991, 2001, 2011 and 2022 are from Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Population Census Wing. The 2022 Census figures are based on preliminary results.

Demographics

[edit]Muslims are the predominant religion with 93.40%, while Hindus are main minority with 6.26% population. Christians and others are 0.28% and 0.06% respectively. Out of 44,213,278 population, 41,295,740 are Muslims, 2,766,723 are Hindus, 124,349 are Christians, 20,341 are Buddhist, with some other faiths small population.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ "List of Divisional Commissioners". Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- ^ "ঢাকা বিভাগ". Archived from the original on 2021-10-28. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g National Report (PDF). Population and Housing Census 2022. Vol. 1. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. November 2023. p. 386. ISBN 978-9844752016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-09-25. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ "TelluBase—Dhaka Fact Sheet (Tellusant Public Service Series)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-07-18. Retrieved 2024-01-11.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Subnational HDI - Table - Global Data Lab". Archived from the original on 2022-09-25. Retrieved 2022-09-25.

- ^ a b Sajahan Miah (2012). "Dhaka Division". In Sirajul Islam and Ahmed A. Jamal (ed.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 2015-07-01. Retrieved 2015-07-01.

- ^ "Census 2022: Dhaka division home to 44 million people now". 27 July 2022. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Dhaka". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 26 June 2023. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

Dhaka's name is said to refer to the dhak tree, once common in the area, or to Dhakeshwari ("The Hidden Goddess"), whose shrine is located in the western part of the city.

- ^ Ayan, Anindya J. (28 January 2018). "History of Dhaka's origin". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

In history, it is often believed that Raja Ballal Sen of the Sen Dynasty of Bengal founded the Dhakeshwari Temple in the 12th century to mark the place of his birth and to pay tribute to the patron goddess of this region. The name Dhaka is believed to have originated from Dhakeshwari in the same way Athens got its name from Athena, the patron goddess of the Greek city.

- ^ "Islam Khan Chisti". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Chowdhury, A.M. (23 April 2007). "Dhaka". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ^ a b Mamoon, Muntassir (2010) [First published 1993]. Dhaka: Smiriti Bismiritir Nogori. Anannya. p. 94.

- ^ "Dhaka". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Dhaka City Corporation (5 September 2006). "Pre-Mughal Dhaka (before 1608)". Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ "From Jahangirnagar to Dhaka". Forum. The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "A tale of Baro-Bhuiyans". The Independent. Dhaka. 5 December 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ a b Abdul Karim (2012). "Bara Bhuiyans, The". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

- ^ Sharif Ahmad Shamim (19 Nov 2017). ঈশা খাঁর কবর গাজীপুরে! [Isa Khar Qobor Gazipure]. Kaler Kantho (in Bengali). Gazipur. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Shah Jahan's Dhaka visit before he became the Mughal emperor". 7 September 2023. Archived from the original on 8 September 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Historical Background for the Establishment of Naib-Nazimship (Deputy Governorship for the four Divisions of Subah Bangla), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- ^ Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760, page 202, University of California Press

- ^ Kraas, Frauke; Aggarwal, Surinder; Coy, Martin; Mertins, Günter, eds. (2013). Megacities: Our Global Urban Future. Springer. p. 60. ISBN 978-90-481-3417-5.

- ^ Shay, Christopher. "Travel – Saving Dhaka's heritage". BBC. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ a b Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Bhawal Estate". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

- ^ Apurba Jahangir (2016-05-13). "The Haunted Estate". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 2020-06-26. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- ^ a b "Fathabad". Banglapedia.

- ^ "Faridpur". global.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2021-03-10.

- ^ "Rare 1857 reports on Bengal uprisings". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Railway". Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "History of Electricity in Bangladesh | Thcapriciousboy". Tusher.kobiraj.com. 18 July 2013. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "Eastern Bengal and Assam - Encyclopedia". theodora.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Out of place, out of time". Himal Southasian. 26 March 2019. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "How politics and architecture blended in Dhaka". The Daily Star (Opinion). 20 August 2018. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Unthreading Partition: The politics of jute sharing between two Bengals". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 6 November 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ "Part II: Formulation of Urban and Transport Plan" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Dhaka Population 2020". Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Hossain, Shahadat (January 2008). "Rapid Urban Growth and Poverty in Dhaka City" (PDF). Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology. 5 (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Dhaka: fastest growing megacity in the world". The World from PRX. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.