Documerica

Documerica (portmanteau of "document" and "America"; stylized as DOCUMERICA) was a program sponsored by the United States Environmental Protection Agency to "photographically document subjects of environmental concern" in the United States from about 1972 to 1977.[1][2][3] The collection, now at the National Archives, contains over 22,000 photographs,[4] more than 15,000 of which are available online.[5][6][7]

Scope

[edit]

With support from the first EPA administrator, William Ruckelshaus, project director Gifford D. Hampshire contracted well-known photographers to work for the EPA on the project.[8][9] Estimates of the number involved range between 70[10] and 120,[8] including Erik Calonius, Dennis Cowals, Gene Daniels, Ken Hayman, Anne LaBastille, Danny Lyon, Boyd Norton, Yoichi Okamoto, Charles O'Rear, Marc St. Gil, Flip Schulke, Tomas Sennett, Bill Strode, Suzanne Szasz, Arthur Tress and John H. White.[1] They were organized geographically, with each photographer working in a particular area in which they were already active. For example, Michael Philip Manheim worked in Boston;[2][5] Jack Corn focused on West Virginia and Tennessee;[2][5] Bill Gillette documented miners in Colorado;[5] and Marc St. Gil focused primarily on Leakey, Houston and San Antonio, Texas.[11]

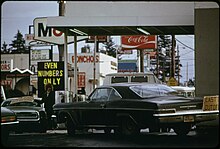

Subjects photographed include urban cityscapes, small towns, rural areas, beaches and mountains. They show people going about their everyday lives as well as working in farms; waterfronts; mining and logging, industry and heavy industry. Images document junk yards, highways, Amtrak trains, air and water pollution; and environmental protection and pollution control measures.[12][13] The earliest assignments were closely aligned to the EPA's proposed areas of concern: air and water pollution, management of solid waste, radiation and pesticides, and noise abatement.[14]: 153 However, photographers had considerable creative freedom about what they shot.[4]As has been discussed by Gisela Parak, photographers working with Documerica were involved in the creation of a new pictorial language to articulate environmental issues.[14]: 155 Among the areas depicted are national parks and forests, including environmentally sensitive areas that were under development or considered for government protection, such as the planned route of the Alaska Pipeline, Hawaii and Washington, D.C. Photographers used differing approaches: Boyd Norton's photographs often emphasize the natural beauty of an area,[14]: 156 while Alexander Hope's photographs of the Middletown, Rhode Island dump and salt marsh reveal complex inter-relationships of man and nature.[14]: 165–167

Details

[edit]

Photographers working for the Documerica project received $150 a day (equivalent to $1,093 in 2023[15]), along with film and expenses.[4] More than 80,000 photographs were submitted to Gifford D. Hampshire.[16] A selection were kept to become part of the collection, while copies and the unselected images were returned to the photographers. Because the images were part of a federal government project, photographers were required to waive their copyright, placing the images in the public domain.[17]

Like the photographers of the Federal photographic project of the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression,[18] some of the Documerica photographers interpreted their mission rather broadly, and sometimes artistically. Many of the photographs preserve a distinct visual record of time and place.[19]

Public access

[edit]Perhaps a quarter of the images were publicly shown during the 1970s.[16] A group of 155 photographs was shown in an exhibition Documerica 1 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. for six weeks in the summer of 1972. A number of small traveling exhibits were sent to cities such as New Orleans, Cincinnati, Dallas, and Philadelphia, and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES) created the exhibit Our Only World for display at the EPA's Visitors Center and as a traveling exhibit.[5]

Digital scans of over 15,000 of the original 35 mm color slides and black-and-white negatives and prints are available through the National Archives and Records Administration's Archival Research Catalog.[20][21]

The quality of the images varies. Older copies made from the original color transparency films tend to be inferior to the quality of the originals.[17] In 2013, the National Archives in Washington, D.C., displayed a curated exhibition, "Searching for the Seventies: The Documerica Photography Project". Curator Bruce Bustard selected a set of images from the Documerica collection and arranged to reprint them from the original slides. The quality of the resulting color images was much higher than that of older color reprints, which had degraded.[4] One hundred reprinted images from the Documerica project were reprinted in the exhibition book Searching for the Seventies: The Documerica Photography Project (2013), edited by Bruce I. Bustard.[13][22]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 2013 the string quartet Ethel created a multimedia show called Ethel's Documerica which incorporated images from the DOCUMERICA archives.[10] The show premiered at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and went on a national tour managed by Baylin Artists Management.[23]

Gallery

[edit]-

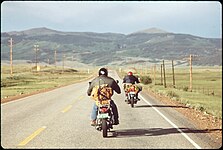

Bikers in Colorado, 1972, Boyd Norton

-

Fertilizing the Imperial Valley, CA, 1972, Charles O'Rear

-

Suburbanization, Orange County, CA, 1975, Charles O'Rear

-

Nature in New York City, 1974, Suzanne Szasz

-

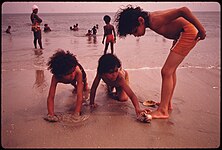

Children at a Brooklyn beach, 1974, Danny Lyon

-

63rd Street, Chicago, 1973, John H. White

-

Duck killed by polluted pond, Utah, 1974, Bruce McAllister

-

Air pollution, Cleveland, OH, 1973, Frank John Aleksandrowicz

-

Jesse Jackson, Chicago, 1973, John H. White

-

Future terminus of Trans-Alaska Pipeline, 1974, Dennis Cowals

-

Testing in the black lung laboratory, West Virginia, 1974, Jack Corn

References

[edit]- ^ a b "DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, 1972 - 1977". National Archives Catalog. Archived from the original on May 12, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c Ruiz, Matthew Ismael (March 7, 2013). "Searching for the Seventies: The Documerica Photography Project A new gallery show explores some amazing American documentary photography". Popular Photography. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ Kathke, Torsten (February 17, 2017). "Your Photography Is Political". FStoppers. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Rosenberg, David (July 4, 2013). "Searching for the '70s and Finding America". Slate. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Simmons, C. Jerry (Spring 2009). "DOCUMERICA: Snapshots of Crisis and Cure in the 1970s". Prologue Magazine. 41 (1). Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Alan (November 16, 2011). "DOCUMERICA: Images of America in Crisis in the 1970s". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Alan (July 22, 2013). "America in the 1970s: New York City (first of five part series)". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Holley, Joe (September 2, 2004). "Journalist Gifford D. Hampshire, 80". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (April 27, 2017). "Documerica, a photo time capsule of the '70s, should be resurrected". Curbed. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Smith, Steve (October 4, 2013). "New Music Bonds With Vintage Images". The New York Times.

- ^ "Marc St. Gil's Finest Shots From The Texas DOCUMERICA Series". Austinist. October 10, 2012.

- ^ "Sorry No Gas: Photos from Documerica, 1972 – 1975". We are the mutants. March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Bustard, Bruce I. (2013). Searching for the seventies : the DOCUMERICA photography project. London: D Giles Limited. ISBN 978-1907804151.

- ^ a b c d Parak, Gisela (January 26, 2016). Photographs of Environmental Phenomena: Scientific Images in the Wake of Environmental Awareness, USA 1860s-1970s. Germany: Transcript-Verlag. pp. 146-. ISBN 978-3837630855. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Walsh, Dylan (January 4, 2012). "A Photographic Blast From the Past". The New York Times. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Archibald, Roger (January 15, 2012). "Long dormant EPA photojournalism project being rediscovered and revived". Society of Environmental Journalists.

- ^ Shubinski, Barbara Lynn (2009). From FSA to EPA: Project Documerica, the Dustbowl Legacy, and the Quest to Photograph 1970s America (PhD thesis). University of Iowa. doi:10.17077/etd.ernl7umv. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010.

- ^ Fulleylove, Rebecca. "Martin Joubert celebrates archive images of 1970s America in this series of mags". It's Nice That. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ In "Scope & Contents" page for series DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, compiled 1972 - 1977, National Archives Identifier 542493 / Local Identifier 412-DA; Series from Record Group 412: Records of the Environmental Protection Agency, 1944 - 2000. Record of holdings available from the National Archives Catalog of the National Archives and Records Administration Archived August 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine under the National Archives Identifier 542493. Accessed February 18, 2009.

- ^ Loria, Kevin (October 9, 2017). "Vintage photos taken by the EPA reveal what America looked like before pollution was regulated". Business Insider. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ "Searching for the Seventies U.S. National Archives". Google Arts and Culture. 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ "Baylin Artists Management - Baylin Artists Management".

External links

[edit]- Documerica Project at the National Archives and Records Administration

- Documerica at Flickr

- "Searching for the Seventies U.S. National Archives". Google Arts and Culture. 2015.