Portuguese cuisine

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Portugal |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Music |

| Sport |

The oldest known book on Portuguese cuisine (Portuguese: Cozinha portuguesa), entitled Livro de Cozinha da Infanta D. Maria de Portugal, from the 16th century, describes many popular dishes of meat, fish, poultry and others.[1]

Culinária Portuguesa, by António-Maria De Oliveira Bello, better known as Olleboma, was published in 1936.[2] Despite being relatively restricted to an Atlantic, Celtic sustenance,[3][4] the Portuguese cuisine also has strong French[2] and Mediterranean[5] influences.

The influence of Portugal's spice trade in the East Indies, Africa, and the Americas is also notable, especially in the wide variety of spices used. These spices include piri piri (small, fiery chili peppers), white pepper, black pepper, saffron, paprika, clove, allspice, cumin, cinnamon and nutmeg, used in meat, fish or multiple savoury dishes from Continental Portugal, the Azores and Madeira islands. Cinnamon, vanilla, lemon zest, orange zest, aniseed, clove and allspice are used in many traditional desserts and some savoury dishes.

Garlic and onions are widely used, as are herbs; bay leaf, parsley, oregano, thyme, mint, marjoram, rosemary and coriander are the most prevalent.

Olive oil is one of the bases of Portuguese cuisine, which is used both for cooking and flavouring meals. This has led to a unique classification of olive oils in Portugal, depending on their acidity: 1.5 degrees is only for cooking with (virgin olive oil), anything lower than 1 degree is good for dousing over fish, potatoes and vegetables (extra virgin). 0.7, 0.5 or even 0.3 degrees are for those who do not enjoy the taste of olive oil at all, or who wish to use it in, say, a mayonnaise or sauce where the taste is meant to be disguised.

Portuguese dishes include meats (pork, beef, poultry mainly also game and others), seafood (fish, crustaceans such as lobster, crab, shrimps, prawns, octopus, and molluscs such as scallops, clams and barnacles), vegetables and legumes and desserts (cakes being the most numerous). Portuguese often consume rice, potatoes, sprouts (known as grelos), and bread with their meals and there are numerous varieties of traditional fresh breads like broa[6][7][8] which may also have regional and national variations within the countries under Lusophone or Galician influence.[2][9] In a wider sense, Portuguese and Galician cuisine share many traditions and features.[10]

Middle Ages

[edit]During the Middle Ages, the Portuguese lived mostly from husbandry. They grew cereals, vegetables, root vegetables, legumes and chestnuts, poultry, cattle, pigs, that they used as sustenance. Fishing and hunting were also common in most regions. During this period, novel methods to conserve fish were introduced, along with plants like vines and olive trees.[11] Bread (rye, wheat, barley, oats) was widely consumed and a staple food for most of the populations.[11] Oranges were introduced in Portugal by Vasco Da Gama in the 15th century. [citation needed] Many of today's foods such as potatoes, tomatoes, chilli, bell peppers, maize, cocoa, vanilla or turkey were unknown in Europe until the post-Columbus arrival in the Americas in 1492.

Meals

[edit]

A Portuguese breakfast often consists of fresh bread, with butter, ham, cheese or jam, accompanied by coffee, milk, tea or hot chocolate. A small espresso coffee (sometimes called a bica after the spout of the coffee machine, or Cimbalino after the Italian coffee machine La Cimbali) is a very popular beverage had during breakfast or after lunch, which is enjoyed at home or at the many cafés in towns and cities throughout Portugal. Sweet pastries are also very popular, as well as breakfast cereal, mixed with milk or yogurt and fruit. The pastel de nata, one of the most salient symbols of the Portuguese cuisine, is a common feature of the Portuguese breakfast. They are frequently enjoyed with a shot of espresso, both at breakfast or as an afternoon treat.

Lunch, often lasting over an hour, is served between noon and 2 o'clock, typically around 1 o'clock and dinner is generally served around 8 o'clock. There are three main courses, with lunch and dinner usually including a soup. A common Portuguese soup is caldo verde, which consists of a base of cooked, then pureed, potato, onion and garlic, to which shredded collard greens are then added. Slices of chouriço (a smoked or spicy Portuguese sausage) are often added as well, but may be omitted, thereby making the soup fully vegan.

Among fish recipes, salted cod (bacalhau) dishes are pervasive. The most popular desserts are caramel custard, known as pudim de ovos or flã de caramelo, chocolate mousse known as mousse de chocolate,[12] crème brûlée known as leite-creme,[13] rice pudding known as arroz doce[14] decorated with cinnamon, and apple tart known as tarte de maçã. Also a wide variety of cheeses made from sheep, goat or cow's milk. These cheeses can also contain a mixture of different kinds of milk. The most famous are queijo da serra from the region of Serra da Estrela, queijo São Jorge from the island of São Jorge, and requeijão.[15] A popular pastry is the pastel de nata, a small custard tart often sprinkled with cinnamon.

Fish and seafood

[edit]

Portugal is a seafaring nation with a well-developed fishing industry and this is reflected in the amount of fish and seafood eaten. The country has Europe's highest fish consumption per capita, and is among the top four in the world for this indicator.[16][17] Fish is served grilled, boiled (including poached and simmered), fried or deep-fried, stewed known as caldeirada (often in clay pot cooking), roasted, or even steamed.

Foremost amongst these is bacalhau (cod), which is the type of fish most consumed in Portugal. It is said that there are more than 365 ways to cook cod,[18] meaning at least one dish for each day of the year. Cod is almost always used dried and salted, because the Portuguese fishing tradition in the North Atlantic developed before the invention of refrigeration—therefore it needs to be soaked in water or sometimes milk before cooking. The simpler fish dishes are often flavoured with virgin olive oil and white wine vinegar.

Portugal has been fishing and trading cod since the 15th century, and this cod trade accounts for its widespread use in the cuisine. Other popular seafoods includes fresh sardines (especially as sardinhas assadas),[19] sea bass, snapper, swordfish, mackerel, sole, brill, halibut, John Dory, turbot, monkfish, octopus, squid, cuttlefish, crabs, shrimp and prawns, lobster, spiny lobster, and many other crustaceans, such as barnacles, hake, horse mackerel (scad), scabbard (especially in Madeira), and a great variety of other fish and shellfish, as well as molluscs, such as clams, mussels, oysters, scallops and periwinkles.

Caldeirada is a range of different stews consisting of a variety of fish (turbot, monkfish, hake, mussels) and shellfish, resembling the Provençal bouillabaisse, or meats and games, together with multiple vegetable ingredients. These stews traditionally consist of (rapini) grelos,[20] and/or potatoes, tomatoes, peri-peri, bell peppers, parsley, garlic, onions, pennyroyal, and in some regions, coriander.

River lamprey and eels are considered fresh water delicacies. The Coimbra and Aveiro regions of central Portugal, are renowned for eel stews[21] and lamprey seasonal dishes and festivals.[22] Arganil and Penacova have popular dishes such as Arroz de Lampreia or Lampreia à Bordalesa.[23][24]

Sardines used to be preserved in brine for sale in rural areas. Later, sardine canneries developed all along the Portuguese coast. Ray fish is dried in the sun in Northern Portugal. Canned tuna is widely available in Continental Portugal. Tuna used to be plentiful in the waters of the Algarve. They were trapped in fixed nets when they passed the Portuguese southern coast on their way to spawn in the Mediterranean, and again when they returned to the Atlantic. Portuguese writer Raul Brandão, in his book Os Pescadores, describes how the tuna was hooked from the raised net into the boats, and how the fishermen would amuse themselves riding the larger fish around the net. Fresh tuna, however, is usually eaten in Madeira and the Algarve where tuna steaks are an important item in local cuisine. Canned sardines or tuna, served with boiled potatoes, black-eyed peas, collard greens and hard-boiled eggs, constitute a convenient meal when there is no time to prepare anything more elaborate.

Meat and poultry

[edit]

Eating meat and poultry on a daily basis was historically a privilege of the upper classes. Pork and beef are the most common meats in the country. Meat was a staple at the nobleman's table during the Middle Ages. A Portuguese Renaissance chronicler, Garcia de Resende, describes how an entrée at a royal banquet was composed of a whole roasted ox garnished with a circle of chickens. A common Portuguese dish, mainly eaten in winter, is cozido à portuguesa, which somewhat parallels the French pot-au-feu or the New England boiled dinner. Its composition depends on the cook's imagination and budget. An extensive lavish cozido may include beef, pork, salt pork, several types of charcutaria (such as cured chouriço, morcela e chouriço de sangue, linguiça, farinheira, etc.), pig's feet, cured ham, potatoes, carrots, turnips, cabbage and rice. This would originally have been a favourite food of the affluent farmer, which later reached the tables of the urban bourgeoisie and typical restaurants.

Meat

[edit]

Tripas à moda do Porto (tripe with white beans) is said to have originated in the 14th century, when the Castilians laid siege to Lisbon and blockaded the Tagus entrance. The Portuguese chronicler Fernão Lopes dramatically recounts how starvation spread all over the city. Food prices rose astronomically, and small boys would go to the former wheat market place in search of a few grains on the ground, which they would eagerly put in their mouths when found. Old and sick people, as well as prostitutes, or in short anybody who would not be able to aid in the city's defence, were sent out to the Castilian camp, only to be returned to Lisbon by the invaders. It was at this point that the citizens of Porto decided to organize a supply fleet that managed to slip through the river blockade. Apparently, since all available meat was sent to the capital for a while, Porto residents were limited to tripe and other organs. Others claim that it was only in 1415 that Porto deprived itself of meat to supply the expedition that conquered the city of Ceuta. Whatever the truth may be, since at least the 17th century, people from Porto have been known as tripeiros or tripe eaters. Another Portuguese dish with tripe is dobrada.

Nowadays, the Porto region is equally known for the toasted sandwich known as a francesinha (meaning "Frenchie").

Many other meat dishes feature in Portuguese cuisine. In the Bairrada area, a famous dish is Leitão à Bairrada (roasted suckling pig). Nearby, another dish, chanfana (goat slowly cooked in red wine, paprika and white pepper) is claimed by two towns, Miranda do Corvo ("Capital da Chanfana")[25] and Vila Nova de Poiares ("Capital Universal da Chanfana").[26] Carne de porco à alentejana, fried pork with clams, is a popular dish with some speculation behind its name and its origin as clams would not be as popular in Alentejo, a region with only one sizeable fishing port, Sines, and small fishing villages but would instead have a much popular usage in the Algarve and its seaside towns. One of the theories as to why the plate may belong to the Algarve is that pigs in the region used to be fed with fish derivatives, so clams were added to the fried pork to disguise the fishy taste of the meat.[27] The dish was used in the Middle Ages to test Jewish converts' new Christian faith; consisting of pork and shellfish (two non-kosher items), Cristãos-novos were expected to eat the dish in public in order to prove they had renounced the Jewish faith.[28] In Alto Alentejo (North Alentejo), there is a dish made with lungs, blood and liver, of either pork or lamb. This traditional Easter dish is eaten at other times of year as well. A regional, islander dish, alcatra, beef marinated in red wine, garlic and spices like cloves and whole allspice, then roasted in a clay pot, is a tradition of Terceira Island in the Azores.

The Portuguese steak, bife, is a slice of fried beef or pork marinated in spices and served in a wine-based sauce with fried potatoes, rice, or salad. An egg, sunny-side up, may be placed on top of the meat, in which case the dish acquires a new name, bife com ovo a cavalo (steak with an egg on horseback). This dish is sometimes referred to as bitoque, to demonstrate the idea that the meat only "touches" the grill twice, meaning that it does not grill for too long before being served, resulting in a rare to medium-rare cut of meat. Another variation of bife is bife à casa (house steak), which may resemble the bife a cavalo[29] or may feature garnishing, such as asparagus.[30]

Iscas (fried liver) was a favourite request in old Lisbon taverns. Sometimes, they were called iscas com elas, the elas referring to sautéed potatoes. Small beef or pork steaks in a roll (pregos or bifanas, respectively) are popular snacks, often served at beer halls with a large mug of beer. In modern days, a prego or bifana, eaten at a snack bar counter, may constitute lunch in itself. Espetada (meat on a skewer) is very popular in the island of Madeira.

Charcuterie

[edit]

Alheira,[31] a yellowish sausage from Trás-os-Montes, traditionally served with fried potatoes and a fried egg, has an interesting story. In the late 15th century, King Manuel of Portugal ordered all resident Jews to convert to Christianity or leave the country. The King did not really want to expel the Jews, who constituted the economic and professional élite of the kingdom, but was forced to do so by outside pressures. So, when the deadline arrived, he announced that no ships were available for those who refused conversion—the vast majority—and had men, women and children dragged to churches for a forced mass baptism. Others were even baptized near the ships themselves, which gave birth to a concept popular at the time: baptizados em pé, literally meaning: "baptized while standing". It is believed that some of the Jews maintained their religion secretly, but tried to show an image of being good Christians. Since avoiding pork was a tell-tale practice in the eyes of the Portuguese Inquisition, new Christians devised a type of sausage that would give the appearance of being made with pork, but only contained heavily spiced game and chicken. Over time, pork has been added to the alheiras. Alheira-sausage varieties with PGI protection status, include Alheira de Vinhais and Alheira de Barroso-Montalegre.[32][33]

Chouriço or Chouriça (the latter usually denoting a larger or thicker version) is a distinct sausage and not to be confused with chorizo. It is made (at least) with pork, fat, paprika, garlic, and salt (wine and sometimes pepper also being common ingredients in some regions). It is then stuffed into natural casings from pig or lamb and slowly dried over smoke.[34] The many different varieties differ in color, shape, spices and taste. White pepper, piri-piri, cumin and cinnamon are often an addition in Portuguese ex-colonies and islands. Traditional Portuguese cured chouriço varieties are more meaty, often use red wine and not many spices.[35] Many Portuguese dishes use chouriço, including cozido à portuguesa and feijoada.[36]

Farinheira is another Portuguese smoked sausage, which uses wheat flour as base ingredient. This sausage is one of the ingredients of traditional dishes like Cozido à Portuguesa. Borba, Estremoz and Portalegre farinheiras all have a "PGI" in the European Union.[37][38]

Presunto (prosciutto ham) comes in a wide variety in Portugal, the most famous presunto being from the Chaves region. Presunto is usually cut in thin slices or small pieces and consumed as aperitif, tea, or added as ingredient to different dishes.

Several varieties of presunto are protected by European law with protected designations of origin (PDO) or protected geographical indication (PGI), such as Presunto de Barrancos or Presunto Bísaro de Vinhais.[39][40]

Porco bísaro is a prized native pig breed in Portugal with PDO status.[41] Several products derived from this breed, such as «Bucho de Vinhais», «Chouriço de Ossos de Vinhais» and «Chouriça Doce de Vinhais» also have PGI status. According to the General Cattle Census on the Continent of the Kingdom of Portugal (1870), "... bísaro is the name given to the tucked-up pig, more or less leggy, with loose ears to distinguish him from the good plump and pernicious pig of the Alentejo". The name Celtic is proposed and used by Sanson to express the antiquity of the race of this type, which was the only one that existed in the regions inhabited by the Celtic people,[42] such as the north of Portugal and Galicia, the former Gaul and the British islands, before the introduction in these countries, of the Asian and Romanesque races.

In 1878, Macedo Pinto described the bísaro pig as an animal belonging to the Typo Bizaro or Celta, with the morphological characteristics mentioned above, distinguishing two varieties within the breed, according to the corpulence, color and greater or lesser amount of bristles.

He considered the existence of pigs from 200 to 250 kg of carcass and others between 120 and 150 kg; as for color, he says they are mostly black, also some spotted and those with white fur were called Galegos, as they come from Galicia. Molarinhos were spotted animals that had few bristles and smooth, smooth skin. The same author also mentions that they are animals of slow and late growth, difficult to fatten (only completing their growth at the age of two), producing more lean meat than fat and accumulating more in the fat than in thick blankets of bacon. In 1946, Cunha Ortigosa classifies the Bísara breed, originally from the Celtic family, as one of the three national breeds. When describing the varieties within the breed, in addition to Galega and Beirôa which encompasses the Molarinho and Cerdões subtypes.[43]

Portuguese cold cuts and sausages (charcutaria and enchidos, respectively) have long and varied traditions in meat preparation, seasoning, preservation and consumption: cured, salted, smoked, cooked, simmered, fermented, fried, wrapped, dried. Regional variations in form and flavour, specialities and names also occur. Further pork (and other meats) charcuterie products include toucinho, paio, morcela, beloura, bucho, butelo, cacholeira, maranho, pernil, salpicão and others.[44][45]

Poultry

[edit]

Chicken, duck, turkey, red-legged partridge and quail are all elements of Portuguese cuisine. Dishes include frango no churrasco (chicken on churrasco), chicken piri-piri, cabidela rice, canja de galinha, and arroz de pato (duck rice), among others.

Turkeys were only eaten for Christmas or on special occasions, such as wedding receptions or banquets. Until the 1930s, farmers from the outskirts of Lisbon would come around Christmastime to bring herds of turkeys to the city streets for sale. Nowadays, mass production in poultry farms makes these meats accessible to all classes. Bifes de peru, turkey steaks, have thus become an addition to Portuguese tables.

Vegetables and starches

[edit]

Vegetables that are popular in Portuguese cookery include numerous cabbage and collard varieties, sprouts[46] (traditionally collected from turnips and different cabbage shoots) tomatoes, onions and peas. There are many starchy dishes, such as feijoada, a rich black bean stew with beef and pork, and açorda, a Portuguese bread soup. Numerous ’’cozido’’ stews are prepared from kale, white beans, red beans, Catarino and Bragançano, fava beans, black eyed beans. Several pumpkins like menina and porqueira[47] varietals, are used in soups and soufflés.[48] One of numerous vegetable and starch rich soups and broths is caurdo or caldo à Lavrador, a soup made of cabbage, red beans, potatoes, prosciutto chunks and wheat flour.[49]

Many dishes are served with salads often made from tomato, lettuce, shredded carrots and onion, usually seasoned with olive oil and vinegar. Potatoes and rice are also extremely common in Portuguese cuisine. Soups made from a variety of vegetables, root vegetables, meats and beans are commonly available, one of the most popular being caldo verde, made from thinly sliced kale, potato purée, and slices of chouriço.

Fruits, nuts, and berries

[edit]

Before the arrival of potatoes from the New World, chestnuts (Castanea sativa) were widely used as seasonal staple ingredients. There is a revival of chestnut dishes, desserts and compotes in Portugal and production is relevant in inland areas of central and northern Portugal.[50][51]

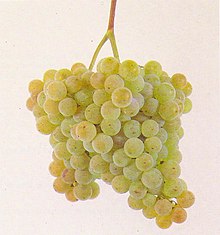

Other seasonal fruits, nuts and berries such as pears,[52] apples,[53] table grapes, plums, peaches, cherries, sour cherries,[54] melons, watermelons, citrus, figs,[55] pomegranates, apricots, walnuts, pine nuts, almonds, hazelnuts, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, redcurrant and blueberries[56][57] are part of the Portuguese diet. These are consumed naturally or used as desserts, marmalades, compotes, jellies and liqueurs.[58][59]

Cheese

[edit]

There are a wide variety of Portuguese cheeses, made from cow's, goat's or sheep's milk. Usually these are very strongly flavoured and fragrant. Traditional Portuguese cuisine does not include cheese in its recipes, so it is usually eaten on its own before or after the main dishes. The Queijo da Serra da Estrela, which is very strong in flavour, can be eaten soft or more matured. Serra da Estrela is handmade from fresh sheep's milk and thistle-derived rennet. In the Azores islands, there is a type of cheese made from cow's milk with a spicy taste, the Queijo São Jorge. Other well known cheeses with protected designation of origin, such as Queijo de Azeitão, Queijo de Castelo Branco. Queijo mestiço de Tolosa , is the only Portuguese cheese with protected geographical indication[60] and is made in the civil parish of Tolosa, part of the municipality of Nisa, which itself has another local variation within the Portalegre District, Queijo de Nisa.

Coffee

[edit]Alcoholic beverages

[edit]Wines and beers

[edit]

Wine (red, white and "green") is the traditional Portuguese drink, the rosé variety being popular in non-Portuguese markets and not particularly common in Portugal itself. Vinho verde, termed "green" wine, is a specific kind of wine which can be red, white or rosé, and is only produced in the northwestern (Minho province) and does not refer to the colour of the drink, but to the fact that this wine needs to be drunk "young". A "green wine" should be consumed as a new wine while a "maduro" wine usually can be consumed after a period of ageing. Green wines are usually slightly sparkling.

Traditionally grown on the schist slopes of the River Douro and immediate tributaries, Port wine is a fortified wine of distinct flavour produced in Douro, which is normally served with desserts.

Alvarinho white wines from Minho are also highly sought after.[62]

Vinho da Madeira, is a regional wine produced in Madeira, similar to sherry. From the distillation of grape wastes from wine production, this is then turned into a variety of brandies (called aguardente, literally "burning water"), which are very strong-tasting. Typical liqueurs, such as Licor Beirão and Ginjinha, are very popular alcoholic beverages in Portugal. In the south, particularly the Algarve, a distilled spirit called medronho, which is made from the fruit of the strawberry tree.

Beer was already consumed in Pre-Roman times, namely by the Lusitanians who drank beer much more than wine. The Latinised word ‘cerveja’ (from cerevisia < cervesia) derives from an older Celtic term used in Gaul.[63][64] During the Reconquista, many knights from Northern Europe preferred beer to the local wine.[65] The ‘Biergarten’ culture, called Cervejaria in Portugal, is widespread in all regions and several local brands are popular with locals and visitors alike. Lisbon has a Beer Museum focusing on Portuguese and Lusophone countries' beer traditions.[66]

Pastries and sweets

[edit]

Portuguese sweets have had a large impact on the development of Western cuisines. Many words like marmalade, caramel, molasses and sugar have Portuguese origins.

The Portuguese sponge cake called pão de ló is believed to be based on the 17th century French recipe pain de lof, which in turn derived from Dutch "loef".[67] The French eventually called their cake Genoise.

Probably the most famous of the Portuguese patisseries are the pastéis de nata, originally known as Pastéis de Belém in the Lisbon district with the same name in the early nineteenth century. It is unclear when and where the recipe was first started. Monks of the military-religious Order of Christ lived in a church on the same location and provided assistance to seafarers in transit since the early fourteenth century, at least.[68]

The House of Aviz and the Jerónimos Monastery followed, the monastery lastly being occupied by the Hieronymite monks. Following the 1820 liberal revolution, events led to the closure of all monastic orders. The Pastéis de Belém were first commercialised just outside the Jerónimos monastery by people who had lost their jobs there. The original patisserie, adjacent to the monastery still operates today.[69] This pastry is now found worldwide, it is known in the UK by its original name or also as Portuguese custard tart. In 2011, the Portuguese public voted on a list of over 70 national dishes. Eventually naming the pastel de nata one of the seven wonders of Portuguese gastronomy.[70]

Many of the country's typical pastries were created in the Middle Ages monasteries by nuns and monks and sold as a means of supplementing their incomes. The names of these desserts are usually related to monastic life; barriga de freira (nun's belly), papos d’anjo (angel's double chin), and toucinho do céu (bacon from heaven). For that reason, they are often referred to as doçaria conventual or receitas monásticas (monastic recipes).[71] Their legacy dates back to the 15th century when sugar from overseas became easier to access by all classes. Nuns at the time, were often young nobles who inherited knowledge from their households and developed recipes. These recipes were passed and perfected from generation to generation, usually within the secrecy of convents. Many of today's Portuguese desserts originated in convents and monasteries.[72]

The Andalusian influence in Southern Portugal can be found in sweets that incorporate figs, almonds and honey, namely the Algarve marzipan colourful sweets,[73] or the almond tuiles, known as telhas d’amêndoa.

Most towns have a local specialty, usually egg or cream-based pastry. Some examples are leite-creme (a dessert consisting of an egg custard-base topped with a layer of hard caramel, a variant of creme brûlée) and pudim flã.

Other very popular pastries found in most cafés, bakeries and pastry shops across the country are the Bola de Berlim, the Bolo de arroz, and the Tentúgal pastries.[74]

Doce de gila (made from chilacayote squash), wafer paper, and candied egg threads called fios de ovos or angel hair.[75]

-

Pão-de-Ló

-

Rabanadas and filhós, typical Christmas dessert

-

Leite-creme (Portuguese Crème brûlée)

-

Arroz Doce (Rice pudding)

-

Bola de Berlim (a type of Berliner)

-

Salame de Chocolate (Chocolate salami)

Influences on world cuisine

[edit]

Portugal formerly had a large empire and the cuisine has been influenced in both directions. Other Portuguese influences reside in the Chinese territory of Macau (Macanese cuisine) and territories who were part of the Portuguese India, such as Goa or Kerala, where vindalho (a spicy curry), shows the pairing of vinegar, chilli pepper and garlic.

The Persian orange, grown widely in southern Europe since the 11th century, was bitter. Sweet oranges were brought from India to Europe in the 15th century by Portuguese traders. Some Southeast Indo-European languages name the orange after Portugal, which was formerly its main source of imports.

Examples are Albanian portokall, Bulgarian portokal [портокал], Greek portokali [πορτοκάλι], Persian porteghal [پرتقال], and Romanian portocală. In South Italian dialects (Neapolitan), the orange is named portogallo or purtualle, literally "the Portuguese ones". Related names can also be found in other languages: Turkish Portakal, Arabic al-burtuqal [البرتقال], Amharic birtukan [ቢርቱካን], and Georgian phortokhali [ფორთოხალი].

The Portuguese imported spices, such as cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) now liberally used in its traditional desserts and savoury dishes, from Asia.[76]

The Portuguese "canja", chicken soup made with pasta or rice, is a popular food therapy for the sick, which shares similarities with the Asian congee, used in the same way, indicating it may have come from the East.[77]

In 1543, Portuguese trade ships reached Japan and introduced refined sugar, valued there as a luxury good. Japanese lords enjoyed Portuguese confectionery so much it was remodelled in the now traditional Japanese konpeitō (candy), kasutera (sponge cake), and keiran somen (the Japanese version of Portuguese "fios de ovos", also popular in Thai cuisine under the name of "kanom foy tong"),[78] creating the Nanban-gashi, or "New-Style Wagashi". During this Nanban trade period, tempura (resembling Portuguese peixinhos da horta) was introduced to Japan by early Portuguese missionaries.

Tea was made fashionable in England in the 1660s after the marriage of King Charles II to the Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza (Catarina De Bragança), who brought her liking for tea, originally from the colony of Macau, to the court.[79] When Catherine relocated up north to join King Charles, she is said to have packed loose-leaf tea as part of her personal belongings; it would also have likely been part of her dowry. Queen Catherine also introduced marmalade to the English and made the habit of eating with a fork a part of the court's table etiquette.[80]

All over the world, Portuguese immigrants influenced the cuisine of their new "homelands", such as Hawaii and parts of New England. Pão doce (Portuguese sweet bread), malassadas, sopa de feijão (bean soup), and Portuguese sausages (such as linguiça and chouriço) are eaten regularly in the Hawaiian islands by families of all ethnicities. Similarly, the "papo-seco" is a Portuguese bread roll with an open texture, which has become a staple of cafés in Jersey, where there is a substantial Portuguese community.

In Australia and Canada, variants of "Portuguese-style" chicken, sold principally in fast food outlets, have become extremely popular in the last two decades.[81][82][83] Offerings include conventional chicken dishes and a variety of chicken and beef burgers. In some cases, such as "Portuguese chicken sandwiches", the dishes offered bear only a loose connection to Portuguese cuisine, usually only the use of "piri-piri sauce" (a Portuguese sauce made with piri piri).

The Portuguese had a major influence on African cuisine and vice versa. They are responsible for introducing corn in the African continent. In turn, the South African restaurant chain Nando's, among others, have helped diffusing Portuguese cuisine worldwide, in Asia for example, where the East Timorese cuisine also received influence.[84]

Madeira wine and early American history

[edit]

In the 18th century Madeira wine became extremely popular in British America. Barrel-aged Madeira especially was a luxury product consumed by wealthy European colonists. The price continued to rise from £5 at the start of the 18th century to £43 by the early 19th century. It was even served as a toast during the First Continental Congress in 1775.[85]

Madeira was an important wine in the history of the United States of America.[86] No wine-quality grapes could be grown among the 13 colonies, so imports were needed, with a great focus on Madeira.[87] One of the major events on the road to revolution in which Madeira played a key role was the seizure of John Hancock's sloop the Liberty on 9 May 1768 by British customs officials. Hancock's boat was seized after he had unloaded a cargo of 25 casks (3,150 gallons) of Madeira wine, and a dispute arose over import duties. The seizure of the Liberty caused riots to erupt among the people of Boston.

Madeira wine was a favorite of Thomas Jefferson after George Wythe introduced him to it.[88] It was used to toast The Declaration of Independence and George Washington, Betsy Ross,[89] Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams are also said to have appreciated the qualities of Madeira. The wine was mentioned in Benjamin Franklin's autobiography. On one occasion, Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail, of the great quantities of Madeira he consumed while a Massachusetts delegate to the Continental Congress. A bottle of Madeira was used by visiting Captain James Server to christen the USS Constitution in 1797. Chief Justice John Marshall was also known to appreciate Madeira, as did his fellow justices on the early U.S. Supreme Court.

See also

[edit]- Broa de Avintes, a bread from Avintes

- Portuguese sweet bread

- Mediterranean diet

- List of Portuguese dishes

- Galician cuisine

- Macanese cuisine

- Mozambican cuisine

- Seafood

- Brazilian cuisine

- Cape Verdean cuisine

- Angolan cuisine

References

[edit]- ^ "Livro de Cozinha da Infanta D. Maria de Portugal". Livro de Cozinha da Infanta D. Maria de Portugal. 24 March 2012.

- ^ a b c Guerreiro, Fábio Banza (January 2018). ""Uma Cozinha Portuguesa, com certeza: A 'Culinária Portuguesa' de António Maria de Oliveira Bello", in Revista Trilhas da História, Vol.8, n.º15, Três Lagoas, 2018, pp. 221-236". Revista Trilhas da História – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ MacVeigh, Jeremy (26 August 2008). International Cuisine. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1111799700 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Portugal's Past Can Be Seen In Its Cuisine". 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Why Portuguese Influence Is the Next Food Trend in Europe | host". host.fieramilano.it.

- ^ Verbete "broa" no dicionario Priberam (in Portuguese).

- ^ Vigo, Faro de (21 April 2014). "Broa". Faro de Vigo (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Pão e Produtos de Panificação". Produtos Tradicionais Portugueses.

- ^ "20 pratos da culinária portuguesa de fazer crescer água na boca | momondo Explorador". 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Cociña Galega Tradicional". O Concello de Lalín. 23 July 2020. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ a b Barroca, Mário Jorge (2017). No tempo de D. Afonso Henriques: reflexões sobre o primeiro século português. CITCEM - Centro de Investigação Transdisciplinar Cultura, Espaço e Memória. ISBN 978-989-8351-75-3 – via Sigarra.

- ^ Les origines de la mousse au chocolat

- ^ [1] As 17 melhores sobremesas de Portugal

- ^ Rice in Portugal

- ^ Queijos portugueses. Infopédia [Online]. Porto: Porto Editora, 2003-2013.

- ^ (in Portuguese) PESSOA, M.F.; MENDES, B.; OLIVEIRA, J.S. CULTURAS MARINHAS EM PORTUGAL Archived 29 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, "O consumo médio anual em produtos do mar pela população portuguesa, estima-se em cerca de 58,5 kg/ por habitante sendo, por isso, o maior consumidor em produtos marinhos da Europa e um dos quatro países a nível mundial com uma dieta à base de produtos do mar."

- ^ "Fish and seafood consumption per capita". Our World in Data. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Irreverence and Recreation of 'Bacalhau', the Portuguese Faithful Friend. Brill. 2015. pp. 13–26. doi:10.1163/9781848884496_003. ISBN 9781848884496.

- ^ "Peixes Cozinha de Portugal Gastronomia Peixes Cozinha de Portugal Peixes Portal de Portugal © Top de Portugal". www.topdeportugal.com.

- ^ "Uma_Cozinha_Portuguesa_com_certeza_A_Cu.pdf".

- ^ Figueiredo, Lucia. "Produtos Tradicionais Portugueses". Produtos Tradicionais Portugueses.

- ^ "CM Penacova". www.cm-penacova.pt.

- ^ "Pratos Típicos do Centro de Portugal".

- ^ Rosado, António (22 February 2020). "Festival Gastronómico da Lampreia em Penacova no próximo fim de semana".

- ^ Administrator. "Mas afinal...o que é a Chanfana?". www.bikeonelas.com.

- ^ "Vila Nova de Poiares: Capital Universal da Chanfana".

- ^ Silva, Nuno M. (30 March 2019). "História e origem da Carne de Porco à Alentejana". clubevinhosportugueses.pt. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ Soderstrom, Mary (2010). Making Waves: The Continuing Portuguese Adventure. Véhicule Press. p. 58. ISBN 9781550652925.

- ^ "Bife a Casa (Portuguese House Steak)". Kidbite Lunches. 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Gloria's Restaurant Menu". Gloria's Portuguese Restaurant.

- ^ "Guia Enchidos Portugueses". 14 September 2017.

- ^ Alheira de Barroso-Montalegre in the DOOR Data Base of the European Union.

- ^ Alheira de Vinhais in the DOOR Data Base of the European Union.

- ^ Santos, Nina (23 July 2017). "A Guide to Portugal's Different Sausages". Culture Trip.

- ^ "Montalegre Special "Chouriça" (Fumeiro Barroso) - Portugal Nosso - Gastronomia, Vinhos & Artigos Diversos".

- ^ Poelzl, Volker (15 October 2009). CultureShock! Portugal: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette. ISBN 9789814435628.

- ^ "Farinheira de Estremoz e Borba". European Commission Agriculture and Rural Development. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Farinheira de Portalegre". European Commission Agricultural and Rural Development. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Presunto de Barrancos in the DOOR database of the European Union. Accessed 16 March 2014.

- ^ Presunto de Vinhais ou Presunto Bísaro de Vinhais in the DOOR database of the European Union. Accessed 16 March 2014.

- ^ "DOOR".

- ^ "Associação Nacional dos Criadores de Suínos de Raça Bísara".

- ^ "Carne de Bísaro Transmontano".

- ^ "Manual de Cozinha da Infanta Dona Maria".

- ^ "Arte Nova e Curiosa...se occupaõ em fazer doçes". 1788.

- ^ "Horticultura" (PDF).

- ^ "Curcubitáceas de Trás-os-Montes" (PDF). www.drapn.min-agricultura.pt. 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "Abóbora – Portal do Jardim.com". Portal do Jardim.com – A Ferramenta Essencial do Verdadeiro Jardineiro (in Portuguese). 9 December 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "Caurdo à Lavrador".

- ^ Soares, Carmen (January 2018). ""Um doce e nutritivo fruto: a castanha na história da alimentação e da gastronomia portuguesas"Mesas luso-brasileiras: alimentação, saúde & cultura". In Carmen Soares, Cilene Gomes Ribeiro (Eds.), Mesas Luso-brasileiras: Alimentação, Saúde & Cultura. Vol. 2. Série DIAITA: Scripta & Realia, Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, 103-176. – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ "Centro de Interpretação Vivo do Castanheiro e da Castanha de Aguiar da Beira (CIVCC AB)". www.cm-aguiardabeira.pt.

- ^ Sousa, Rui M. Maia de. "As variedades regionais de pereiras" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Investigação Agrária e Veterinária. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Pereira, Sónia Santos (6 February 2018). "Recuperar as variedades tradicionais de fruta portuguesa". Vida Rural. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Ginja de Óbidos e Alcobaça". European Commission Agriculture and Rural Development. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Figo Seco de Torres Novas". Produtos Tradicionais Portugueses. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Desde 2012 a produção de mirtilos cresceu 700% em Portugal". Agronegocios. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Portugal destaca-se pela qualidade do mirtilo". Agrotec. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Bijos, Pedro (8 July 2012). Portugal Com Gosto. Mauad Editora. ISBN 9788574784885. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Isabel M. R. Mendes Drumond, Braga (September 2012). Bens de hereges: inquisição e cultura material. Coimbra University Press. ISBN 9789892603070. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Registed cheeses from Portugal in the DOOR database of the European Union. Retrieved 26 March 2014

- ^ "Coffee Countries: How a Cup of Joe is Enjoyed Around the World?". huffingtonpost.ca. The Huffington Post. 24 October 2016.

- ^ "EC wine evaluation Portugal" (PDF).

- ^ "Cervoise : définition de CERVOISE, subst. fém. | La langue française". 6 February 2019.

- ^ GOUGENHEIM, Georges (14 January 2010). Les mots français dans l'histoire et dans la vie. Place des éditeurs. ISBN 9782258084179 – via Google Books.

- ^ Aquino, Bruno (25 March 2019). Uma Viagem pelo Mundo da Cerveja Artesanal portuguesa. Leya. ISBN 9789897801129.

- ^ "Museu da Cerveja – Museu da Cerveja".

- ^ "Priberam Dicionário".

- ^ IGESPAR, ed. (2011). "Séc. XVI" (in Portuguese). Lisbon, Portugal: IGESPAR-Instituto de Gestão do Património Arquitectónico e Arqueológico. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ "História". 23 January 2015.

- ^ The National Dish of Portugal. wetravelportugal.com. Accessed 28 March 2021.

- ^ "Sabores e segredos: receituários conventuais portugueses da Época Moderna" (PDF). digitalis-dsp.uc.pt. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Alves, Osvaldo. "Saberes e Sabores: Memórias da Doçaria Conventual de Coimbra" – via www.academia.edu.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Roufs, Timothy G.; Roufs, Kathleen Smyth. Sweet Treats Around the World.

- ^ "The Prettiest Pastries of Portugal, and How to Recognize Them". Vogue. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Fernandes, Daniel. "Produtos Tradicionais Portugueses". Produtos Tradicionais Portugueses.

- ^ "O Português que descobriu a canela". ncultura.pt. 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Hearty Dish set King". newstatesman.com.

- ^ "Wagashi: Angel Hair Keiran Somen (Fios de Ovos)". kyotofoodie.com. 20 December 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "The True Story Behind England's Tea Obsession". bbc.com.

- ^ Brozan, Nadine (11 October 1990). "Here's to the Queen who gave us a name". The New York Times.

- ^ Bird on the wing Sydney Morning Herald, 16 April 2004

- ^ Hill, Megan (26 June 2019). "Portuguese-Style Grilled Chicken Chain Makes Inroads in Western Washington". Eater Seattle.

- ^ "Toronto's best Portuguese chicken". thestar.com. 12 November 2010.

- ^ "Our Journey to East Timor". International Cuisine. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Phillips, Rod (13 October 2014). Alcohol: A History. p. 156. ISBN 9781469617619.

- ^ Tuten, James. ""Have Some Madeira, M'Dear:" The Unique History of Madeira Wine and Its Consumption in the Atlantic World". academia.edu. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Tuten, James H. (2006). "Liquid Assets: Madeira Wine and Cultural Capital among Lowcountry Planters, 1735–1900". American Nineteenth Century History. 6 (2): 173–188. doi:10.1080/14664650500314513. S2CID 144093837.

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson and Madeira: A History and Tasting". Smithsonian. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Bortolot, Lana. "How To Drink Like A President". Forbes. Retrieved 11 July 2020.