Coromantee

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| More than 3 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Current Jamaican English, Jamaican Patwah Dialects Bermudian Patwah, Caicosian Patwah, Caymanian Patwah, Raizal Patwah | |

| Religion | |

| Protestantism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Taíno, Jamaicans of African descent, Belizean Creoles, Caribbean people, Miskito people, Akan, Igbo, Kongolese |

Coromantee, or Cromanty, also called Coromantins, or Koromanti (derived from the name of the Gold Coast slave fort (Fort Cormantin) in the modern-day Ghanaian town of Kormantse), is the name for the ethnic group who were abducted from the Gold Coast, and taken to Jamaica during the Atlantic slave trade.[1] The descendants of the Cromanty are now the predominant ethnic group in Jamaica, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, the Raizal Islands, and the Turks and Caicos Islands; who all share a common Cromanty heritage and ancestry.

Name

[edit]The Dictionary of Jamaican English defines the word “Cromanty” as follows:[2]

1. The place of origin of many of the slaves brought to Jamaica in the late 17th and 18th centuries.

2. A negro brought from and identified with this area; in Jamaica, those who escaped and joined the Maroons came to dominate them and gained a reputation for fierceness.

Etymology

[edit]During the 17th and 18th century, expansionist West African states such as the Ashanti Empire, Fanti Confederacy, Oyo Empire, and the Kingdom of Benin, resorted to ever greater acts of ethnic cleansing, which ultimately culminated in the Atlantic slave trade. Many of the belligerents formed alliances with European powers (such as Britain and the Netherlands), which involved them trafficking the victims of these conflicts to European powers, in exchange for weapons and manufactured goods.[3]

As a result, many states surrounding the Slave Coast began to participate in the trade, with states such as the Fanti Confederacy allying with the British Empire to capture members of the rival Ashanti (with these captives being sent to British colonies such as Jamaica); whilst the Dutch allied Ashanti Empire would capture members of the rival Fanti (who were often sent to Dutch colonies such as Surinam).[4] The name Coromantee, or Cromanty, therefore originates from the town of Kormantse and nearby Fort Cormantin, which is the location where the abducted Cromanty were held before being taken to the West Indies.[5]

History

[edit]Due to their warrior culture the Cromanty organized countless slave rebellions in Jamaica, and became renowned for their legendary fierceness and indomitable spirit.[6] Their rebellious nature became so notorious among the British plantocracy, that an Act was proposed to ban the importation of Cromanty into Jamaica, as they realised that the Cromanty were a proud and fiercely independent people;[7] who fought vehemently to free themselves from slavery.[8]

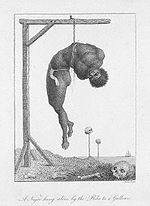

1690 Rebellion

[edit]Several rebellions in the 1700s were attributed to Coromantees. According to enslaver and colonial administrator Edward Long, the first rebellion occurred in 1690 between three or four hundred enslaved people in Clarendon Parish, Jamaica, who, after killing a white owner, seized firearms and provisions and killed an overseer at the neighbouring plantation.[9] A militia formed and eventually suppressed the rebellion, hanging the leader. Several rebels fled and joined the Maroons. Long also describes the incident where an enslaver was overpowered by a group of Coromantees who, after killing him, cut off his head and turned his skull into a drinking bowl. However, the "drinking of blood" is more than likely anti-African propaganda, though Coromantee and especially Asante war tactics were known to use fear in their opponents.[10] In 1739, the leader of the Western Maroons, Cudjoe, signed a treaty with the British, ensuring the Maroons would be left alone, provided they did not help other slave rebellions.[11]

1731 First Maroon War

[edit]Led by Cudjoe and Queen Nanny, the First Maroon War was a conflict between Maroons in Jamaica and the colonial British authorities that reached a climax in 1731. In 1739–40, the British government in Jamaica recognized that it could not defeat the Maroons, so they agreed with them instead. The Maroons were to remain in their five main towns: Accompong, Cudjoe's Town (Trelawny Town), Moore Town (formerly New Nanny Town), Scott's Hall (Jamaica) and Charles Town, Jamaica, living under their own rulers and a British supervisor.

1760 Tacky’s War

[edit]In 1760, another conspiracy known as Tacky's War was hatched. Long claims that almost all enslaved Coromantin on the island were involved without any suspicion from the whites. They planned to overthrow British rule and establish an Cromanti kingdom in Jamaica. Tacky and his forces were able to take over several plantations and kill the white plantation owners. However, they were ultimately betrayed by an enslaved man named Yankee, whom Long describes as wanting to defend his master's house and "assist the white men". Yankee ran to the neighbouring estate and, with the help of another enslaved man, alerted the rest of the plantation owners.[12] The British enlisted the help of Jamaican Maroons, who were themselves descendants of the Akan ethnic group, to defeat the Coromantins. Long describes a British man and a Mulatto man as each having killed three Coromantins.

Eventually, Tacky was killed by a sharpshooter named Davy the Maroon, who was a Maroon officer in Scott's Hall.[13]

1765 Conspiracy

[edit]Coromantee enslaved people were also behind a conspiracy in 1765 to revolt. The leaders of the rebellion sealed their pact with an oath. Coromantee leaders Blackwell and Quamin (Kwame) ambushed and killed a group of colonial militiamen at a fort near Port Maria, Jamaica, as well as other whites in the area.[14] They intended to ally with the Maroons to split up the island. The Coromantins were to give the Maroons the forests while the Coromantins would control the cultivated land. The Maroons did not agree because of their treaty and existing agreement with colonial government.[15]

1766 Rebellion

[edit]Thirty-three newly arrived Coromantins killed at least 19 whites in Westmoreland Parish, Jamaica. It was discovered when a young enslaved girl gave up their plans. All of the conspirators were either executed or sold.[7]

1795 Second Maroon War

[edit]The Second Maroon War of 1795–1796 was an eight-month conflict between the Maroons of Trelawney Town, a maroon settlement created at the end of the First Maroon War, located in the parish of St James, but named after governor Edward Trelawny, and the British colonials who controlled the island. The other Jamaican Maroon communities did not participate in this rebellion, and their treaty with the British remained in place.

Anti-Coromantee measures

[edit]In 1765, a bill was proposed to prevent the importation of Coromantees but was not passed. Edward Long, an anti-Coromantee writer, states:

Such a bill, if passed into law would have struck at very root of evil. No more Coromantins would have been brought to infest this country, but instead of their savage race, the island would have been supplied with Blacks of a more docile tractable disposition and better inclined to peace and agriculture.[7]

Colonists later devised ways of separating Coromantins from each other by housing them separately, placing them with other enslaved people, and stricter monitoring. Since groups such as the Igbos were hardly reported to have been maroons, Igbo women were paired with Coromantee men to subdue the latter due to the idea that Igbo women were bound to their first-born sons' birthplace.[16]

Culture

[edit]

Before being taken captive, Coromantins were usually part of highly organized and stratified Akan groups such as the Asante Empire and the Fante Confederacy. Akan states were not all the same, but the 40 groups in the mid-17th century shared a common political language and culture.[17] These groups also had shared mythology – and a single, supreme God, Nyame – and Anansi stories. These stories spread to the New World and became Anancy, Anansi Drew, or Br'er Rabbit stories in Jamaica, The Bahamas, and the Southern United States, respectively.

According to Long, Akan or "Coromantee" culture obliterated any other African customs, and incoming non-Akan Africans had to submit to the culture of the dominant Akan population in Jamaica. Akan deities referred to as Abosom in the Twi and Fante dialects were documented, and enslaved Akans would praise Nyankopong (erroneously written by the British as Accompong); libations would be poured to Asase Yaa (erroneously written as "Assarci") and Bosom Epo the sea god. Bonsam was referred to as the god of evil. The John Canoe festival was created in Jamaica and the Caribbean by enslaved Akans who sided with the man known as John Canoe. John Canoe was a man from Axim, Ghana, an Akan from the Ahanta. He was a soldier for the Germans until one day, he turned his back on them for his Ahanta people and sided with Nzima and Dutch Fante troops to take the area from the Germans and other Europeans. The news of his victory reached Jamaica, and he was celebrated ever since that Christmas of 1708 when he had first defeated German forces for Axim. Twenty years later, his stronghold was broken by neighboring Fante forces supported by English merchants. This resulted in the Ahanta, Nzima and Asante warriors becoming captives of the Fante and being taken to Jamaica as prisoners of war, numbering some 20,000 men.[9]

Day names

[edit]See also: Cromanty names

The Cromanty also have similar day names to those of the Akan, which can be seen in many common Cromanty names such as: Quashee, Cuffy, and Cubah – corresponding to the Akan names Kwasi, Kofi, and Akua, respectively;[18][19] along with the names of some notable Coromantee leaders – Nanny (Nana), Cudjoe (Kojo), and Tacky (Takyi). Similarly, the word for a Caucasian person: "Obrouni" (Obroni) occurs in both Patwah and Akan.[20]

In fiction

[edit]

Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave is a relatively short work of prose fiction by Aphra Behn (1640–1689),[21] published in 1688, concerning the love of its hero, an enslaved African in Surinam in the 1660s, and the author's own experiences in the new South American colony. Oroonoko is the grandson of a Coromantin African king, Prince Oroonoko, who falls in love with Imoinda, the daughter of that king's top general.[22]

The king, too, falls in love with Imoinda. He gives her the sacred veil, thus commanding her to become one of his wives, even though she has already married Oroonoko. After unwillingly spending time in the king's harem (the Otan), Imoinda and Oroonoko plan a tryst with the help of the sympathetic Onahal and Aboan. They are eventually discovered, and because she has lost her virginity, Imoinda is sold into slavery.[23] The king's guilt, however, leads him to falsely inform Oroonoko that she has been executed since death was thought to be better than slavery. Later, after winning another tribal war, Oroonoko is betrayed and captured by an English captain who plans to enslave him and his men. The captain transports both Imoinda and Oroonoko to the colony of Surinam. The two lovers are reunited there, under the new Christian names of Caesar and Clemene, even though Imoinda's beauty has attracted the unwanted desires of other enslaved people and the Cornish gentleman, Trefry.[24]

Upon Imoinda's pregnancy, Oroonoko petitions for their return to the homeland. But after being continuously ignored, he organizes a slave revolt. The enslaved people are hunted down by the military forces and compelled to surrender on Deputy Governor Byam's promise of amnesty. Yet, when the enslaved people surrender, Oroonoko and the others are punished and whipped. Oroonoko decides to kill Byam to avenge his honor and express his natural worth. But to protect Imoinda from violation and subjugation after his death, he decides to kill her. The two lovers discuss the plan, and with a smile on her face, Imoinda willingly dies by his hand. A few days later, Oroonoko is found mourning by her decapitated body and is kept from killing himself, only to be publicly executed. During his death by dismemberment, Oroonoko calmly smokes a pipe and stoically withstands all the pain without crying out.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Frederic G. Cassidy., Robert B. Le Page (1980). Dictionary of Jamaican English. Cambridge University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-521-11840-8.

- ^ Cassidy & Le Page (1980), p. 131.

- ^ Williams, Eric (1994). Capitalism and Slavery. London: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4488-5.

- ^ Edwards, B. (1972). The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies. United States: Arno Press.

- ^ Crooks, John Joseph (1973), Records Relating to the Gold Coast Settlements from 1750 to 1874 (London: Taylor & Francis), p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7146-1647-6.

- ^ Robinson, Carey (2007). The Iron Thorn: The Defeat of the British by the Jamaican Maroons. Kingston: LMH Publishing ISBN 978-9-7682-0241-3.

- ^ a b c Long (1774), p. 471.

- ^ "Tacky's Revolt". Reason. 21 July 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ a b Long, Edward (1774), The History of Jamaica Or, A General Survey of the Antient and Modern State of that Island: With Reflexions on Its Situation, Settlements, Inhabitants, Climate, Products, Commerce, Laws, and Government (google), vol. 2, pp. 445–475

- ^ Long (1774), p. 447.

- ^ Long (1774), p. 345.

- ^ Long (1774), p. 451.

- ^ Long (1774), p. 468.

- ^ Long (1774), p. 465.

- ^ Long (1774), pp. 460–70.

- ^ Mullin, Michael (1995). Africa in America: slave acculturation and resistance in the American South and the British Caribbean, 1736–1831. University of Illinois Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-252-06446-1.

- ^ Thornton, John (2000), p. 182.

- ^ Egglestone (2001), pdf.

- ^ Egglestone, Ruth (2001). "A Philosophy of Survival: Anancyism in Jamaican Pantomime" (PDF). The Society for Caribbean Studies Annual Conference Papers. 2: 1471–2024. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Frederic G. Cassidy., Robert B. Le Page (1980). Dictionary of Jamaican English. Cambridge University Press. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-521-11840-8.

- ^ "Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave. A True History". Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2006.

- ^ Hutner 1993, p. 1.

- ^ a b Behn, Gallagher and Stern (2000).

- ^ Behn, Gallagher, and Stern (2000), 13.

Sources

[edit]- Behn, A., C. Gallagher, & S. Stern (2000). Oroonoko, or, The royal slave. Bedford Cultural Editions. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

- Williams, Brackette (1990), "Dutchman Ghosts and the History Mystery: Ritual, Colonizer, and Colonized Interpretations of the 1763 Berbice Slave Rebellion", Journal of Historical Sociology, 3 (2): 133–165, doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.1990.tb00094.x.

- Egerton, Douglas R. He Shall Go Out Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey, 2nd edn. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2004.

- Bryant, Joshua (1824). Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara, which broke out on the 18th of August, 1823. Georgetown, Demerara: A. Stevenson at the Guiana Chronicle Office.

Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara, which broke out on the 18th of August, 1823.

- Hutner, Heidi (1993), Rereading Aphra Behn: History, Theory, and Criticism, University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-1443-4

- Hughes, Ben (2021), When I Die I Shall Return to MY Own Land: The New York Slave Revolt of 1712, Westholme Publishing. ISBN 1594163561

- Thornton, John K. (2000). War, the State, and Religious Norms in "Coromantee" Thought: The Ideology of an African American Nation-- Possible pasts: becoming colonial in early America. ISBN 0-8014-8392-1.

- Viotti da Costa, Emília (18 May 1994). Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood: the Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823. ISBN 0-19-510656-3.