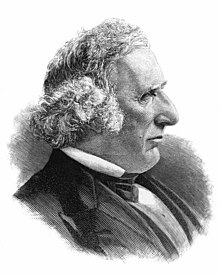

C. K. Garrison

Cornelius Kingsland Garrison | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th Mayor of San Francisco | |

| In office October 3, 1853 – October 1, 1854 | |

| Preceded by | Charles James Brenham |

| Succeeded by | Stephen Palfrey Webb |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 1, 1809 Fort Montgomery, New York, U.S. |

| Died | May 1, 1885 (aged 76) New York City, U.S. |

Cornelius Kingsland Garrison (March 1, 1809 – May 1, 1885) was an American steamboat captain, shipping agent, shipbuilder, capitalist, and politician. He served as the 4th Mayor of San Francisco from 1853 until 1854.

Biography

[edit]He was born on March 1, 1809, in Fort Montgomery, near West Point, New York. During his childhood, he studied architecture and civil engineering while working on his father's schooner.

After moving to Buffalo, New York, in 1830, he worked as a builder, then moving to Canada in 1834 where he built bridges and other marine building projects. He moved to St. Louis no in 1839, where he made a fortune from owning, building, and commanding boats. He later moved to Panama, where he worked as an agent for the Nicaraguan Steamship Company and also established the banking firm of Garrison, Fritz, and Ralston. Garrison also operated steamboats on the Mississippi River.[when?][1]

In 1849, Garrison and Ralph Stover Fretz established a transportation agency in Panama which included banking services and operated as a casino. Garrison earned a reputation as a card hustler from his days on the Mississippi and in Central America.[2][3] Charles Morgan hired him as an agent for his steamship service running through Panama.[3]

On February 1, 1853, Garrison accepted a two-year contract to serve as the San Francisco agent of the Accessory Transit Company, a firm which provided transportation from New York to San Francisco, via Nicaragua. The contract specified a commission of either 2.5 percent or 5 percent of revenue and disbursements, depending on whether he opted to cap his annual salary at $60,000. Cornelius Vanderbilt, a director of the company, recruited him as the Commodore prepared for an extended vacation. Garrison sailed for San Francisco just a few weeks later.[1] In addition to running Accessory Transit Company's agency in San Francisco, he formed a financial partnership with Charles Morgan, founding a bank and collaborating on combinations.[4]

The business partnership of Morgan & Garrison, which Garrison formed with Morgan, was reportedly once the recipient of a brief and now very famous letter: "Gentlemen: You have undertaken to cheat me. I won't sue you, for the law is too slow. I'll ruin you. Yours truly, Cornelius Vanderbilt."[5][6] This letter appears to be apocryphal, however, its only primary source being Vanderbilt's obituary in The New York Times, published almost 25 years after the letter was supposedly written.[7][8][9]

After he moved to San Francisco, he was elected mayor of that city in 1853. After his term as mayor, he returned to New York, where he became a speculator.

During the Civil War, he allowed the U.S. government to use most of his ships. After the war, he bought a large interest in what later became the Missouri Pacific Railroad, which he became president of after it was reorganized. He would also lose a lawsuit which resulted from this reorganization.

He died on May 1, 1885, in New York City of a heart attack. He is interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Stiles, T. J. (2009). The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-375-41542-5.

- ^ Baughman, James P. (1968). Charles Morgan and the Development of Southern Transportation. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. p. 73.

- ^ a b Stiles (2009), p. 274

- ^ Stiles (2009), p. 273

- ^ "Vanderbilt University Register: Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt fought war over route through Central America". Archived from the original on September 24, 2006. Retrieved November 10, 2006.

- ^ "Business Biography". Archived from the original on December 5, 2006. Retrieved November 10, 2006.

- ^ "The Biographer's Blog".

- ^ Stiles (2009), pp. 237–238

- ^ Baughman (1968), pp. 74–75.

- ^ Mosca, Alexandra Kathryn (2008). Green-Wood Cemetery. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7385-5650-5.