Concert pitch

Concert pitch is the pitch reference to which a group of musical instruments are tuned for a performance. Concert pitch may vary from ensemble to ensemble, and has varied widely over time. The ISO defines international standard pitch as A440, setting 440 Hz as the frequency of the A above middle C. Frequencies of other notes are defined relative to this pitch.

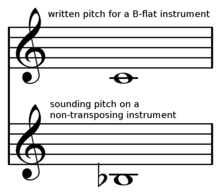

The written pitches for transposing instruments do not match those of non-transposing instruments. For example, a written C on a B♭ clarinet or trumpet sounds as a non-transposing instrument's B♭. The term "concert pitch" is used to refer to the pitch on a non-transposing instrument, to distinguish it from the transposing instrument's written note. The clarinet or trumpet's written C is thus referred to as "concert B♭".[1]

Modern standard concert pitch

[edit]The A above middle C is often set at the international standard of 440 Hz. Historically, this A has been tuned to a variety of different pitches.[2]

History of pitch standards in Western music

[edit]Historically, various standards have been used to fix the pitch of notes at certain frequencies.[3] Various systems of musical tuning have also been used to determine the relative frequency of notes in a scale.

Pre-19th century

[edit]Until the 19th century there was no coordinated effort to standardize musical pitch, and the levels across Europe varied widely. Pitches varied over time, from place to place, and even within the same city. The pitch used for an English cathedral organ in the 17th century, for example, could be as much as five semitones lower than that used for a domestic keyboard instrument in the same city.

Because of the way organs were tuned, the pitch of a single organ could even vary over time. Generally, the end of an organ pipe would be tapped with a cone tuning tool to curve it inwards to raise the pitch, or outwards to lower it.

The tuning fork was invented in 1711, enabling the calibration of pitch, although there was still variation. For example, a 1740 tuning fork associated with Handel is pitched at A = while a specimen from 1780 is pitched at A = about a quarter-tone lower.[4] A tuning fork that belonged to Ludwig van Beethoven around 1800, now in the British Library, is pitched at A = , well over a half-tone higher.[5]

Towards the end of the 18th century there was an overall tendency for the A above middle C to be in the range of to

The frequencies referred to here are based on modern measurements and would not have been precisely known to musicians of the day. Although Mersenne had made a rough determination of sound frequencies as early as the 17th century, such measurements did not become scientifically accurate until the 19th century, beginning with the work of German physicist Johann Scheibler in the 1830s. Frequency is measured in cycles per second (CPS). During the 20th century this term was gradually replaced by hertz (Hz) in honor of Heinrich Hertz.

Pitch inflation

[edit]When instrumental music has risen in prominence (relative to vocal music), there has been a consistent tendency for pitch standards to rise. This led to reform efforts on at least two occasions. At the beginning of the 17th century, Michael Praetorius reported in his encyclopedic Syntagma musicum that pitch levels had become so high that singers were experiencing severe throat strain and lutenists and viol players were complaining of snapped strings. The standard voice ranges he cites show that the pitch level of his time, at least in the part of Germany where he lived, was at least a minor third higher than today's. Solutions to this problem were sporadic and local, but generally involved the establishment of separate standards for voice and organ (German: Chorton, lit. 'choir tone') and for chamber ensembles (German: Kammerton, lit. 'chamber tone'). Where the two were combined, as for example in a cantata, the singers and instrumentalists might use music written in different keys. This kept pitch inflation at bay for some two centuries.[6]

Concert pitch rose further in the 19th century, evidenced by tuning forks of that era in France. The pipe organ tuning fork in Versailles Chapel from 1795 is 390 Hz,[7] an 1810 Paris Opera tuning fork sounds at A = 423 Hz, an 1822 fork gives A = 432 Hz, and an 1855 fork gives A = 449 Hz.[8] At La Scala in Milan the A above middle C rose as high as .[7]

19th- and 20th-century standards

[edit]

Rising pitch put a strain on singers' voices and, largely due to their protests, the French government passed a law on February 16, 1859 setting the A above middle C at 435 Hz, . This was the first attempt to standardize pitch on such a scale, and was known as the diapason normal.[9][7] It became a popular pitch standard outside France as well, and has been known at various times as French pitch, continental pitch or international pitch (this international pitch is not the 1939 "international standard pitch" described below). An 1885 conference in Vienna established this standard in Italy, Austria, Hungary, Russia, Prussia, Saxony, Sweden and Württemberg.[10] This was included as "Convention of 16 and 19 November 1885 regarding the establishment of a concert pitch" in the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 which formally ended World War I.[11] The diapason normal resulted in middle C being tuned at about .

An alternative pitch standard known as philosophical or scientific pitch fixes middle C at (that is, 28 Hz), which places the A above it at approximately in equal temperament tuning. The appeal of this system is its mathematical idealism (the frequencies of all the Cs being powers of two).[12] This never received the same official recognition as the French A = 435 Hz and has not been widely used. This tuning has been promoted unsuccessfully by the LaRouche movement's Schiller Institute under the name Verdi tuning since Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi had proposed a slight lowering of the French tuning system. However, the Schiller Institute's recommended tuning for A of 432 Hz[13][14] uses the Pythagorean ratio of 27:16, rather than the logarithmic ratio of equal temperament tuning.

British attempts at standardization in the 19th century gave rise to the old philharmonic pitch standard of about A = 452 Hz (different sources quote slightly different values), replaced in 1896 by the considerably lower new philharmonic pitch of A = 439 Hz.[15] The high pitch was maintained by Sir Michael Costa for the Crystal Palace Handel Festivals, causing the withdrawal of the principal tenor Sims Reeves in 1877,[16] though at singers' insistence the Birmingham Festival pitch was lowered and the organ retuned at that time. At the Queen's Hall in London, the establishment of the diapason normal for the Promenade Concerts in 1895 (and retuning of the organ to A = 435.5 at 15 °C (59 °F), to be in tune with A = 439 in a heated hall) caused the Royal Philharmonic Society and others (including the Bach Choir, and the Felix Mottl and Arthur Nikisch concerts) to adopt the continental pitch.[17]

In England the term low pitch was used from 1896 onward to refer to the new Philharmonic Society tuning standard of A = 439 Hz at 68 °F (20 °C), while "high pitch" was used for the older tuning of A = 452.4 Hz at 60 °F (16 °C). Although the larger London orchestras were quick to conform to the new low pitch, provincial orchestras continued using the high pitch until at least the 1920s, and most brass bands were still using the high pitch in the mid-1960s.[18][19] Highland pipe bands continue to use an even sharper tuning, around A = 470–480 Hz, over a semitone higher than A440.[20] As a result, bagpipes are often perceived as playing in B♭ despite being notated in A (as if they were transposing instruments in D-flat), and are often tuned to match B♭ brass instruments when the two are required to play together.

In 1834 the Stuttgart Conference of the Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians recommended C264 (A440) as the standard pitch based on Scheibler's studies with his Tonometer.[21] For this reason A440 has been referred to as Stuttgart pitch or Scheibler pitch.

In 1939 an international conference recommended that the A above middle C be tuned to 440 Hz, now known as concert pitch.[22] This was adopted as a technical standard by the International Organization for Standardization in 1955 and reaffirmed by them in 1975 as ISO 16. The difference between this and the diapason normal is due to confusion over the temperature at which the French standard should be measured. The initial standard was A = , but this was superseded by A = 440 Hz, possibly because 439 Hz was difficult to reproduce in a laboratory since 439 is a prime number.[22]

Current concert pitches

[edit]The most common standard around the world is currently[when?] A = 440 Hz.

In practice most orchestras tune to a note given out by the oboe, and most oboists use an electronic tuning device when playing the tuning note. Some orchestras tune using an electronic tone generator.[23] When playing with fixed-pitch instruments such as the piano, the orchestra will generally tune to them—a piano will normally have been tuned to the orchestra's normal pitch. Overall, it is thought that the general trend since the middle of the 20th century has been for standard pitch to rise, though it has been rising far more slowly than it has in the past. Some orchestras like the Berlin Philharmonic now use a slightly lower pitch (443 Hz) than their highest previous standard (445 Hz).[24]

Many modern ensembles which specialize in the performance of Baroque music have agreed on a standard of A = 415 Hz.[25] An exact equal-tempered semitone lower than 440 Hz would be 415.305 Hz, though this is rounded to the nearest integer for simplicity and convenience. In principle this allows for playing along with modern fixed-pitch instruments if their parts are transposed down a semitone. It is, however, common performance practice, especially in the German Baroque idiom, to tune certain works to Chorton, approximately a semitone higher than 440 Hz (460–470 Hz) (e.g., Pre-Leipzig period cantatas of Bach).[26]

Orchestras in Cuba typically use A436 as the pitch so that strings, which are difficult to obtain, last longer. In 2015 American pianist Simone Dinnerstein brought attention to this issue and later traveled to Cuba with strings donated by friends.[27][28]

Controversial claims for 432 Hz

[edit]Particularly in the beginning of the 21st century, many websites and online videos have been published arguing for the adoption of the 432 Hz tuning – often referred to as "Verdi pitch" – instead of the predominant 440 Hz. These claims also include conspiracy theories, related to specious claims of healing properties from 432 Hz pitch, or involving Nazis having favored the 440 Hz tuning.[29][30]

References

[edit]- ^ "Concert Pitch Transposition". bandnotes.info. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ Bruce Haynes (2002). History of Performing Pitch: The Story of "A". Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4185-7.

- ^ "Pitch, temperament and timbre". Dolmetsch Online.

- ^ Mendel, Arthur (1978). "Pitch in Western Music since 1500. A Re-Examination". Acta Musicologica. 50 (1/2): 82. doi:10.2307/932288. ISSN 0001-6241.

Still another fork has acquired what may be more authority than it deserves. Pascal Taskin, harpsichord-maker and tuner to the French Court, owned in 1783 a fork that had been tuned to the oboe of Antoine Sallentin, of the Opera and Chapelle du Roi. Whether Sallentin played the same oboe both in the Opera and in the Chapelle is not known-nor whether Taskin tuned any or all of his instruments to this fork, whose pitch was a1 = 409.

- ^ "Beethoven's tuning fork". British Library. 28 March 2017.

- ^ Michael Praetorius (1991). Syntagma Musicum: Parts I and II. De Organographia. II, Parts 1–2. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198162605.[verification needed]

- ^ a b c Nicholas Thistlethwaite; Geoffrey Webber, eds. (1999). The Cambridge Companion to the Organ. Cambridge University Press. p. 81. ISBN 9781107494039.

- ^ Colin Lawson; Robin Stowell (1999). The Historical Performance of Music: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780521627382.

- ^ Holoman, D. Kern (1989). Berlioz. Harvard University Press. p. 491. ISBN 978-0-674-06778-3.

- ^ Nafziger, James A. R.; Paterson, Robert Kirkwood; Renteln, Alison Dundes (2010). Cultural Law: International, Comparative, and Indigenous. Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-521-86550-0. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Article 282 (22). Treaty of Versailles (PDF). p. 129. Retrieved 8 January 2020 – via Library of Congress.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Funk & Wagnalls New Encyclopedia. Funk & Wagnalls, 1983

- ^ "For a Verdi Opera in the Verdi Tuning in 2001". Schiller Institute. 2001. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ^ Rosen, David (1995). Julian Rushton (ed.). Verdi: Requiem. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780521397674.

- ^ Lloyd, Llewelyn S.; Fould, Achille (1949). "International Standard Musical Pitch". Journal of the Royal Society of Arts. 98 (4810): 85. ISSN 0035-9114.

- ^ J. Sims Reeves, The Life of Sims Reeves, written by himself (Simpkin Marshall, London 1888), 242–252.

- ^ H.J. Wood, My Life of Music (Gollancz, London 1938) Chapters XIV and XV.

- ^ John Walton Capstick (1922). Sound: An Elementary Textbook for Schools and Colleges (second ed.). Cambridge: The University Press. p. 263. ISBN 9781107674585.

- ^ Roy Newsome (2006). The Modern Brass Band: From The 1930s to the New Millennium. Aldershot, Hants; Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Limited (UK); Ashgate Publishing Company (US). pp. 62–63.

- ^ "The Pitch and Scale of the Great Highland Bagpipe". publish.uwo.ca. Retrieved 2017-04-09.

- ^ Rayleigh, J.W.S. (1945). The Theory of Sound, Vol. I. Dover. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-486-60292-9. reprint of 1894 ed.

- ^ a b Lynn Cavanagh. "A brief history of the establishment of international standard pitch a=440 hertz" (PDF).

- ^ "Why does the orchestra always tune to the oboe?". Rockfordsymphony.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-12. Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ Emanuel Eckardt (23 December 2002). "Der Zauber des perfekten Klangs". Die Zeit (in German). Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ^ Albert R. Rice (1992). The Baroque Clarinet. Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780199799046.

- ^ Oxford Composer Companion JS Bach, pp. 369–372. Oxford University Press, 1999

- ^ "Simone Dinnerstein on a Trip to Cuba and Making Music out of Difficulty". NPR. 2015-07-03. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ^ Edgers, Geoff (2017-06-11). "A Brooklyn pianist who can't speak Spanish brings a Cuban orchestra to the United States". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ^ Cross, Alan (13 May 2018). "The great 440 Hz conspiracy, and why all of our music is wrong". Global News. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Marian, Jakub. "The '432 Hz vs. 440 Hz' conspiracy theory". Retrieved 2020-02-22.