Factor XIII

| coagulation factor XIII, A1 polypeptide | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Inactive A1 peptide homodimer with all of the domains and main catalytic residues shown with different colors. | |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | F13A1 | ||||||

| Alt. symbols | F13A | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 2162 | ||||||

| HGNC | 3531 | ||||||

| OMIM | 134570 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_000129 | ||||||

| UniProt | P00488 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| EC number | 2.3.2.13 | ||||||

| Locus | Chr. 6 p24.2-p23 | ||||||

| |||||||

| coagulation factor XIII, B polypeptide | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | F13B | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 2165 | ||||||

| HGNC | 3534 | ||||||

| OMIM | 134580 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_001994 | ||||||

| UniProt | P05160 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 1 q31-q32.1 | ||||||

| |||||||

Factor XIII, or fibrin stabilizing factor, is a plasma protein and zymogen. It is activated by thrombin to factor XIIIa which crosslinks fibrin in coagulation. Deficiency of XIII worsens clot stability and increases bleeding tendency.[1]

Human XIII is a heterotetramer. It consists of 2 enzymatic A peptides and 2 non-enzymatic B peptides. XIIIa is a dimer of activated A peptides.[1]

Function

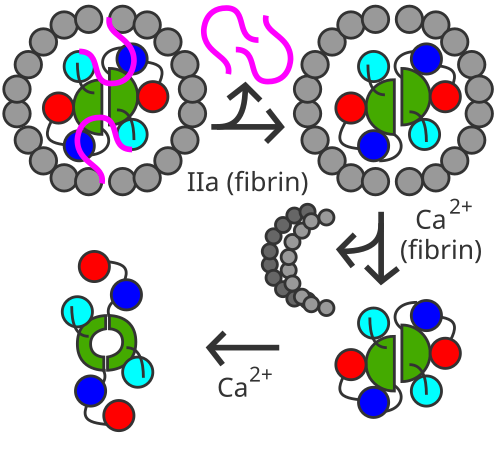

[edit]Within blood, thrombins cleave fibrinogens to fibrins during coagulation and a fibrin-based blood clot forms. Factor XIII is a transglutaminase that circulates in human blood as a heterotetramer of two A and two B subunits. Factor XIII binds to the clot via their B units. In the presence of fibrins, thrombin efficiently cleaves the R37–G38 peptide bond of each A unit within a XIII tetramer. A units release their N-terminal activation peptides.[1]

Both of the non-covalently bound B units are now able to dissociate from the tetramer with the help of calcium ions (Ca2+) in the blood; these ions also activate the remaining dimer of two A units via a conformational change.[1]

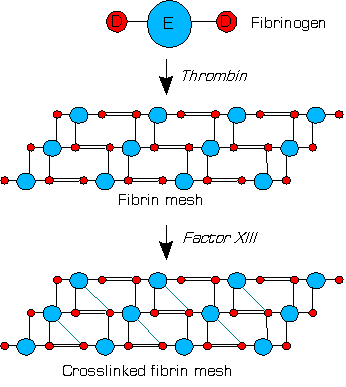

Factor XIIIa (dimer of two active A units) crosslinks fibrins within the clot by forming isopeptide bonds between various glutamines and lysines of the fibrins. These bonds make the clot physically more durable and protect it from premature enzymatic degradation (fibrinolysis).[1]

In humans, plasmin, antithrombin and TFPI are the most relevant proteolytic inhibitors of the active factor XIIIa. α2-macroglobulin is a significant non-proteolytic inhibitor.[1]

-

Activation peptides (pink) of A units are removed by thrombin (IIa) in the presence of fibrin. B units (gray) are released with the help of calcium and A unit dimer is activated (XIIIa forms).

-

XIIIa crosslinks fibrin (simplified picture)

Genetics

[edit]Human factor XIII consist of A and B subunits. A subunit gene is F13A1. It is on chromosome 6 at the position 6p24–25. It spans over 160 kbp, has 14 introns and 15 exons. Its mRNA is 3.9 kbp. It has a 5' UTR of 84 bp and a 3' UTR of 1.6 kbp. F13A1 exon(s)[1]

- 1 code 5' UTR

- 2 code activation peptide

- 2–4 code β-sandwich

- 4–12 code catalytic domain

- 12–13 code β-barrel 1

- 13–15 code β-barrel 2

B subunit gene is F13B. It is on chromosome 1 at the position 1q31–32.1. It spans 28 kpb, has 11 introns and 12 exons. Its mRNA is 2.2 kbp. Exon 1 codes 5' UTR. Exons 2–12 code the 10 different sushi domains.[1]

Structure

[edit]Factor XIII of human blood is a heterotetramer of two A and two B linear polypeptides or "units". A units are potentially catalytic; B units are not. A units form a dimeric center. Non-covalently bound B units form a ring-like structure around the center. B units are removed when XIII is activated to XIIIa. Dimers containing only A units also occur within cells such as platelets. Large quantities of singular B units (monomers) also occur within blood. These dimers and monomers are not known to participate in coagulation, whereas the tetramers do.[1]

A units have a mass of about 83 kDa, 731 amino acid residues, 5 protein domains (listed from the N-terminal to C-terminal, residue numbers are in brackets):[1]

- activation peptide (1–37)

- β-sandwich (38–184)

- catalytic domain (185–515), in which the residues C314, H373, D396 and W279 partake in catalysis

- β-barrel 1 (516–628)

- β-barrel 2 (629–731)

B units are glycoproteins. Each has a mass of about 80 kDa (8.5% of the mass is from carbohydrates), 641 residues and 10 sushi domains. Each domain has about 60 residues and 2 internal disulfide bonds.[1]

Physiology

[edit]A subunits of human factor XIII are made primarily by platelets and other cells of bone marrow origin. B subunits are secreted into blood by hepatocytes. A and B units combine within blood to form heterotetramers of two A units and two B units. Blood plasma concentration of the heterotetramers is 14–48 mg/L and half-life is 9–14 days.[1]

A clot that has not been stabilized by FXIIIa is soluble in 5 mol/L urea, while a stabilized clot is resistant to this phenomenon.[2]

Factor XIII deficiency

[edit]Factor XIII deficiency, while generally rare, does occur, with Iran having the highest global incidence of the disorder with 473 cases. The city of Khash, located in Sistan and Balochistan provinces, has the highest incidence in Iran, with a high rate of consanguineous marriage.[3]

Diagnostic use

[edit]Factor XIII levels are not measured routinely, but may be considered in patients with an unexplained bleeding tendency. As the enzyme is quite specific for monocytes and macrophages, determination of the presence of factor XIII may be used to identify and classify malignant diseases involving these cells.[4]

Discovery

[edit]Factor XIII Deficiency is also known as Laki–Lorand factor, after Kalman Laki and Laszlo Lorand, the scientists who first proposed its existence in 1948.[2] A 2005 conference recommended standardization of nomenclature.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Muszbek L, Bereczky Z, Bagoly Z, Komáromi I, Katona É (July 2011). "Factor XIII: a coagulation factor with multiple plasmatic and cellular functions". Physiological Reviews. 91 (3): 931–72. doi:10.1152/physrev.00016.2010. PMID 21742792. S2CID 24703788.

- ^ a b Laki K, Lóránd L (September 1948). "On the Solubility of Fibrin Clots". Science. 108 (2802): 280. Bibcode:1948Sci...108..280L. doi:10.1126/science.108.2802.280. PMID 17842715.

- ^ Dorgalaleh A, Naderi M, Hosseini MS, Alizadeh S, Hosseini S, Tabibian S, et al. (2015). "Factor XIII Deficiency in Iran: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis". 41 (3): 323–29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Muszbek L, Ariëns RA, Ichinose A (January 2007). "Factor XIII: recommended terms and abbreviations". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 5 (1): 181–83. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02182.x. PMID 16938124. S2CID 20424049.