Charles Dickens: Difference between revisions

Sir Joseph (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by Bradzrules7 (talk) to last revision by Yossiea (HG) |

Bradzrules7 (talk | contribs) typo |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

'''Charles John Huffam Dickens''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|tʃ|ɑr|l|z|_|ˈ|d|ɪ|k|ɪ|n|z}}; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the [[Victorian period]]. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic novels and characters.<ref>[http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/05/23/news/23web-dickens.php "Victorian squalor and hi-tech gadgetry: Dickens World to open in England"], ''The New York Times'', 23 May 2007.</ref> |

'''Charles John Huffam Dickens''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|tʃ|ɑr|l|z|_|ˈ|d|ɪ|k|ɪ|n|z}}; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the [[Victorian period]]. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic novels and characters.<ref>[http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/05/23/news/23web-dickens.php "Victorian squalor and hi-tech gadgetry: Dickens World to open in England"], ''The New York Times'', 23 May 2007.</ref> |

||

Many of his writings were originally published [[Serial (literature)|serially]], in monthly instalments or parts, a format of publication which Dickens himself helped |

Many of his writings were originally published [[Serial (literature)|serially]], in monthly instalments or parts, a format of publication which Dickens himself helped popularise at that time. Unlike other authors who completed entire novels before serialisation, Dickens often created the episodes as they were being serialised. The practice lent his stories a particular rhythm, punctuated by [[cliffhangers]] to keep the public looking forward to the next instalment.<ref>Stone, Harry. ''Dickens' Working Notes for His Novels''. Chicago, 1987.</ref> The continuing popularity of his novels and short stories is such that they have never gone [[Out-of-print book|out of print]].<ref name=AHP>Swift, Simon. [http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2007/apr/18/classics.travelnews "What the Dickens?"], ''The Guardian'', 18 April 2007.</ref> |

||

Dickens' work has been highly praised for its [[realism]], comedy, mastery of prose, unique personalities and concern for [[Reform movement|social reform]] by writers such as [[Leo Tolstoy]], [[George Gissing]] and [[G.K. Chesterton]]; though others, such as [[Henry James]] and [[Virginia Woolf]], have criticised it for sentimentality and implausibility.<ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/20071207125820/http://humwww.ucsc.edu/dickens/OMF/james.html Henry James, "Our Mutual Friend"], ''The Nation'', 21 December 1865.</ref> |

Dickens' work has been highly praised for its [[realism]], comedy, mastery of prose, unique personalities and concern for [[Reform movement|social reform]] by writers such as [[Leo Tolstoy]], [[George Gissing]] and [[G.K. Chesterton]]; though others, such as [[Henry James]] and [[Virginia Woolf]], have criticised it for sentimentality and implausibility.<ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/20071207125820/http://humwww.ucsc.edu/dickens/OMF/james.html Henry James, "Our Mutual Friend"], ''The Nation'', 21 December 1865.</ref> |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

===Early years=== |

===Early years=== |

||

[[Image:ChathamOrdnanceTerrCrop.jpg|left|thumb|180px|2 Ordnance Terrace, [[Chatham, Kent|Chatham]], Dickens's home 1817–1822]] |

[[Image:ChathamOrdnanceTerrCrop.jpg|left|thumb|180px|2 Ordnance Terrace, [[Chatham, Kent|Chatham]], Dickens's home 1817–1822]] |

||

Charles Dickens was born at Landport, in Portsea, on February 7, 1812, to [[John Dickens|John]] and [[Elizabeth Dickens]]. He was the second of their eight children. His father was a clerk in the Navy Pay-office, and was temporarily on duty in the neighbourhood. Very soon after the birth of Charles Dickens, however, the family moved for a short period to Norfolk Street, Bloomsbury, and then for a long period to Chatham, in Kent, which thus became the real home, and for all serious purposes, the native place of Dickens. His early years seem to have been idyllic, although he thought himself a "very small and not-over-particularly-taken-care-of boy".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp/~matsuoka/CD-Forster-1.html |title=John Forster, ''The Life of Charles Dickens'', Book 1, Chapter 2 |publisher=Lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp |accessdate=24 July 2009}}</ref> He spent time outdoors, but also read voraciously, especially the [[picaresque novel]]s of [[Tobias Smollett]] and [[Henry Fielding]]. He spoke, later in life, of his poignant memories of childhood, and of his near-photographic memory of the people and events, which he used in his writing. His father's brief period as a clerk in the Navy Pay Office afforded Charles a few years of private education at |

Charles Dickens was born at Landport, in Portsea, on February 7, 1812, to [[John Dickens|John]] and [[Elizabeth Dickens]]. He was the second of their eight children. His father was a clerk in the Navy Pay-office, and was temporarily on duty in the neighbourhood. Very soon after the birth of Charles Dickens, however, the family moved for a short period to Norfolk Street, Bloomsbury, and then for a long period to Chatham, in Kent, which thus became the real home, and for all serious purposes, the native place of Dickens. His early years seem to have been idyllic, although he thought himself a "very small and not-over-particularly-taken-care-of boy".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp/~matsuoka/CD-Forster-1.html |title=John Forster, ''The Life of Charles Dickens'', Book 1, Chapter 2 |publisher=Lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp |accessdate=24 July 2009}}</ref> He spent time outdoors, but also read voraciously, especially the [[picaresque novel]]s of [[Tobias Smollett]] and [[Henry Fielding]]. He spoke, later in life, of his poignant memories of childhood, and of his near-photographic memory of the people and events, which he used in his writing. His father's brief period as a clerk in the Navy Pay Office afforded Charles a few years of private education at Willy Guzzerlers's School, in [[Chatham, Kent|Chatham]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Jordan|first=John|title=The Cambridge companion to Charles Dickens|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge, England|year=2001|page=xvi|chapter=Chronology|isbn=0-521-66964-2}}</ref> |

||

This period came to an abrupt end when the Dickens family, because of financial difficulties, moved from Kent to Camden Town, in London in 1822. [[John Dickens]], continually living beyond his means, was eventually imprisoned in the [[Marshalsea]] [[debtor's prison]] in Southwark, London in 1824. Shortly afterwards, the rest of his family joined him – except 12-year-old Charles, who boarded with family friend Elizabeth Roylance in [[Camden Town]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Pope-Hennessy|first=Una |authorlink=Una Pope-Hennessy|title=Charles Dickens 1812–1870|publisher=Chatto and Windus|location=London|year=1945|page=11|chapter=The Family Background|isbn=0897607627}}</ref> Mrs. Roylance was "a [[poverty|reduced]] old lady, long known to our family", whom Dickens later immortalised, "with a few alterations and embellishments", as "Mrs. Pipchin", in ''[[Dombey and Son]]''. Later, he lived in a "back-attic...at the house of an insolvent-court agent...in [[Lant Street]] in [[Southwark|The Borough]]...he was a fat, good-natured, kind old gentleman, with a quiet old wife"; and he had a very innocent grown-up son; these three were the inspiration for the Garland family in ''[[The Old Curiosity Shop]]''.<ref name=gutenberg>[http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25851/25851-h/25851-h.htm Project Gutenberg's ''Life of Charles Dickens'' (James R. Osgood & Company, 1875), by John Forster, Volume I, Chapter II, accessed 2 August 2008]</ref> |

This period came to an abrupt end when the Dickens family, because of financial difficulties, moved from Kent to Camden Town, in London in 1822. [[John Dickens]], continually living beyond his means, was eventually imprisoned in the [[Marshalsea]] [[debtor's prison]] in Southwark, London in 1824. Shortly afterwards, the rest of his family joined him – except 12-year-old Charles, who boarded with family friend Elizabeth Roylance in [[Camden Town]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Pope-Hennessy|first=Una |authorlink=Una Pope-Hennessy|title=Charles Dickens 1812–1870|publisher=Chatto and Windus|location=London|year=1945|page=11|chapter=The Family Background|isbn=0897607627}}</ref> Mrs. Roylance was "a [[poverty|reduced]] old lady, long known to our family", whom Dickens later immortalised, "with a few alterations and embellishments", as "Mrs. Pipchin", in ''[[Dombey and Son]]''. Later, he lived in a "back-attic...at the house of an insolvent-court agent...in [[Lant Street]] in [[Southwark|The Borough]]...he was a fat, good-natured, kind old gentleman, with a quiet old wife"; and he had a very innocent grown-up son; these three were the inspiration for the Garland family in ''[[The Old Curiosity Shop]]''.<ref name=gutenberg>[http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25851/25851-h/25851-h.htm Project Gutenberg's ''Life of Charles Dickens'' (James R. Osgood & Company, 1875), by John Forster, Volume I, Chapter II, accessed 2 August 2008]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 10:33, 23 November 2011

Charles Dickens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Charles John Huffam Dickens 7 February 1812 Landport, Portsmouth, England |

| Died | 9 June 1870 (aged 58) Gad's Hill Place, Higham, Kent, England |

| Resting place | Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | British |

| Citizenship | UK |

| Years active | 1833–1870 |

| Notable works | Sketches by Boz, The Old Curiosity Shop, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, Barnaby Rudge, A Christmas Carol, Martin Chuzzlewit, A Tale of Two Cities, David Copperfield, Great Expectations, Bleak House, Little Dorrit, Hard Times, Our Mutual Friend, The Pickwick Papers |

| Spouse | Catherine Thomson Hogarth |

| Children | Charles Dickens, Jr., Mary Dickens, Kate Perugini, Walter Landor Dickens, Francis, Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson Dickens, Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens, Henry Fielding Dickens, Dora Annie Dickens, and Edward Dickens |

| Parents | John Dickens Elizabeth Dickens |

| Signature | |

| |

Charles John Huffam Dickens (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈtʃɑːrlz ˈdɪkɪnz/; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic novels and characters.[1]

Many of his writings were originally published serially, in monthly instalments or parts, a format of publication which Dickens himself helped popularise at that time. Unlike other authors who completed entire novels before serialisation, Dickens often created the episodes as they were being serialised. The practice lent his stories a particular rhythm, punctuated by cliffhangers to keep the public looking forward to the next instalment.[2] The continuing popularity of his novels and short stories is such that they have never gone out of print.[3]

Dickens' work has been highly praised for its realism, comedy, mastery of prose, unique personalities and concern for social reform by writers such as Leo Tolstoy, George Gissing and G.K. Chesterton; though others, such as Henry James and Virginia Woolf, have criticised it for sentimentality and implausibility.[4]

Life

Early years

Charles Dickens was born at Landport, in Portsea, on February 7, 1812, to John and Elizabeth Dickens. He was the second of their eight children. His father was a clerk in the Navy Pay-office, and was temporarily on duty in the neighbourhood. Very soon after the birth of Charles Dickens, however, the family moved for a short period to Norfolk Street, Bloomsbury, and then for a long period to Chatham, in Kent, which thus became the real home, and for all serious purposes, the native place of Dickens. His early years seem to have been idyllic, although he thought himself a "very small and not-over-particularly-taken-care-of boy".[5] He spent time outdoors, but also read voraciously, especially the picaresque novels of Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding. He spoke, later in life, of his poignant memories of childhood, and of his near-photographic memory of the people and events, which he used in his writing. His father's brief period as a clerk in the Navy Pay Office afforded Charles a few years of private education at Willy Guzzerlers's School, in Chatham.[6]

This period came to an abrupt end when the Dickens family, because of financial difficulties, moved from Kent to Camden Town, in London in 1822. John Dickens, continually living beyond his means, was eventually imprisoned in the Marshalsea debtor's prison in Southwark, London in 1824. Shortly afterwards, the rest of his family joined him – except 12-year-old Charles, who boarded with family friend Elizabeth Roylance in Camden Town.[7] Mrs. Roylance was "a reduced old lady, long known to our family", whom Dickens later immortalised, "with a few alterations and embellishments", as "Mrs. Pipchin", in Dombey and Son. Later, he lived in a "back-attic...at the house of an insolvent-court agent...in Lant Street in The Borough...he was a fat, good-natured, kind old gentleman, with a quiet old wife"; and he had a very innocent grown-up son; these three were the inspiration for the Garland family in The Old Curiosity Shop.[8]

On Sundays, Dickens and his sister Frances ("Fanny") were allowed out from the Royal Academy of Music and spent the day at the Marshalsea.[9] (Dickens later used the prison as a setting in Little Dorrit). To pay for his board and to help his family, Dickens was forced to leave school and began working ten-hour days at Warren's Blacking Warehouse, on Hungerford Stairs, near the present Charing Cross railway station. He earned six shillings a week pasting labels on blacking. The strenuous – and often cruel – work conditions made a deep impression on Dickens, and later influenced his fiction and essays, forming the foundation of his interest in the reform of socio-economic and labour conditions, the rigors of which he believed were unfairly borne by the poor. He would later write that he wondered "how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age." As told to John Forster (from The Life of Charles Dickens):

The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river. There was a recess in it, in which I was to sit and work. My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking; first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper; to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat, all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary's shop. When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label, and then go on again with more pots. Two or three other boys were kept at similar duty down-stairs on similar wages. One of them came up, in a ragged apron and a paper cap, on the first Monday morning, to show me the trick of using the string and tying the knot. His name was Bob Fagin; and I took the liberty of using his name, long afterwards, in Oliver Twist.[8]

After only a few months in Marshalsea, John Dickens' paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Dickens, died and bequeathed him the sum of £450. On the expectation of this legacy, Dickens was granted release from prison. Under the Insolvent Debtors Act, Dickens arranged for payment of his creditors, and he and his family left Marshalsea for the home of Mrs. Roylance.

Although Charles eventually attended the Wellington House Academy in North London, his mother Elizabeth Dickens did not immediately remove him from the boot-blacking factory. The incident may have done much to confirm Dickens's view that a father should rule the family, a mother find her proper sphere inside the home. "I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back." His mother's failure to request his return was no doubt a factor in his dissatisfied attitude towards women.'[9]

Righteous anger stemming from his own situation and the conditions under which working-class people lived became major themes of his works, and it was this unhappy period in his youth to which he alluded in his favourite, and most autobiographical, novel, David Copperfield:[10] "I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support, of any kind, from anyone, that I can call to mind, as I hope to go to heaven!" The Wellington House Academy was not a good school. 'Much of the haphazard, desultory teaching, poor discipline punctuated by the headmaster's sadistic brutality, the seedy ushers and general run-down atmosphere, are embodied in Mr. Creakle's Establishment in David Copperfield.'[9] Dickens worked at the law office of Ellis and Blackmore, attorneys, of Holborn Court, Gray's Inn, as a junior clerk from May 1827 to November 1828. Then, having learned Gurneys system of shorthand in his spare time, he left to become a freelance reporter. A distant relative, Thomas Charlton, was a freelance reporter at Doctors' Commons, and Dickens was able to share his box there to report the legal proceedings for nearly four years.[11] This education informed works such as Nicholas Nickleby, Dombey and Son, and especially Bleak House—whose vivid portrayal of the machinations and bureaucracy of the legal system did much to enlighten the general public, and was a vehicle for dissemination of Dickens's own views regarding, particularly, the heavy burden on the poor who were forced by circumstances to "go to law".

In 1830, Dickens met his first love, Maria Beadnell, thought to have been the model for the character Dora in David Copperfield. Maria's parents disapproved of the courtship and effectively ended the relationship by sending her to school in Paris.

Journalism and early novels

In 1833, Dickens' first story, A Dinner at Poplar Walk was published in the London periodical, Monthly Magazine. The following year he rented rooms at Furnival's Inn becoming a political journalist, reporting on parliamentary debate and travelling across Britain to cover election campaigns for the Morning Chronicle. His journalism, in the form of sketches in periodicals, formed his first collection of pieces Sketches by Boz, published in 1836. This led to the serialisation of his first novel, The Pickwick Papers, in March 1836. He continued to contribute to and edit journals throughout his literary career.

In 1836, Dickens accepted the job of editor of Bentley's Miscellany, a position he held for three years, until he fell out with the owner. At the same time, his success as a novelist continued, producing Oliver Twist (1837–39), Nicholas Nickleby (1838–39), The Old Curiosity Shop and, finally, Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty as part of the Master Humphrey's Clock series (1840–41)—all published in monthly instalments before being made into books. During this period Dickens kept a pet raven named Grip, which he had stuffed when it died in 1841. (It is now at the Free Library of Philadelphia).[12]

On 2 April 1836, he married Catherine Thomson Hogarth (1816–1879), the daughter of George Hogarth, editor of the Evening Chronicle. After a brief honeymoon in Chalk, Kent, they set up home in Bloomsbury. They had ten children:[13]

- Charles Culliford Boz Dickens (C. C. B. Dickens), later known as Charles Dickens, Jr., editor of All the Year Round, and author of the Dickens's Dictionary of London (1879).

- Mary Dickens

- Kate Macready Dickens

- Walter Landor Dickens

- Francis Jeffrey Dickens

- Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson Dickens

- Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens

- Sir Henry Fielding Dickens

- Dora Annie Dickens

- Edward Dickens

Dickens and his family lived at 48 Doughty Street, London, (on which he had a three year lease at £80 a year) from 25 March 1837 until December 1839. Dickens's younger brother Frederick and Catherine's 17-year-old sister Mary moved in with them. Dickens became very attached to Mary, and she died in his arms after a brief illness in 1837. She became a character in many of his books, and her death is fictionalised as the death of Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop.[14]

First visit to America

In 1842, Dickens and his wife made his first trip to the United States and Canada, a journey which was successful in spite of his support for the abolition of slavery. It is described in the travelogue American Notes for General Circulation and is also the basis of some of the episodes in Martin Chuzzlewit(1843-44). Dickens includes in Notes a powerful condemnation of slavery,[15] with "ample proof" of the "atrocities" he found. [16] He also called upon President John Tyler at the White House.[17].

During his visit, Dickens spent a month in New York City, giving lectures, raising support for copyright laws, and recording many of his impressions of America. He met such luminaries as Washington Irving and William Cullen Bryant. On 14 February 1842, a Boz Ball was held in his honour at the Park Theater, with 3,000 guests. Among the neighbourhoods he visited were Five Points, Wall Street, The Bowery, and the prison known as The Tombs.[18] At this time Georgina Hogarth, another sister of Catherine, joined the Dickens household, now living at Devonshire Terrace, Marylebone, to care for the young family they had left behind.[19] She remained with them as housekeeper, organiser, adviser and friend until her brother-in-law's death in 1870).

Shortly thereafter, he began to show interest in Unitarian Christianity, although he remained an Anglican for the rest of his life.[20] Soon after his return to England, Dickens began work on the first of his two or three famous Yuletide tales A Christmas Carol written in 1843, which was followed by The Chimes in 1844 and The Cricket on the Hearth in 1845. Of these "A Christmas Carol" is beyond comparison the best as well as the most popular and did much to rekindle the joy of Christmas in Britain and America when the traditional celebration of Christmas was in decline. The seeds for the story were planted in Dickens' mind during a trip to Manchester to witness conditions of the manufacturing workers there. This, along with scenes he had recently witnessed at the Field Lane Ragged School, caused Dickens to resolve to "strike a sledge hammer blow" for the poor. As the idea for the story took shape and the writing began in earnest, Dickens became engrossed in the book. He wrote that as the tale unfolded he "wept and laughed, and wept again' and that he 'walked about the black streets of London fifteen or twenty miles many a night when all sober folks had gone to bed." A Christmas Carol continues to be relevant, sending a message that cuts through the materialistic trappings of the season and gets to the heart and soul of the holidays. After living briefly abroad in Italy (1844) Dickens travelled to Switzerland (1846), it was here he began work on Dombey and Son (1846-48). This and David Copperfield (1849–50) marks a significant artistic break in Dickens' career as his novels became more serious in theme and more carefully planned than his early works.

Philanthropy

In May 1846, Angela Burdett Coutts, heir to the Coutts banking fortune, approached Dickens about setting up a home for the redemption of "fallen" women. Coutts envisioned a home that would differ from existing institutions, which offered a harsh and punishing regimen for these women, and instead provide an environment where they could learn to read and write and become proficient in domestic household chores so as to re-integrate them into society. After initially resisting, Dickens eventually founded the home, named Urania Cottage, in the Lime Grove section of Shepherds Bush. He became involved in many aspects of its day-to-day running, setting the house rules, reviewing the accounts and interviewing prospective residents, some of whom became characters in his books. He would scour prisons and workhouses for potentially suitable candidates and relied on friends, such as the Magistrate John Hardwick to bring them to his attention. Each potential candidate was given a printed invitation written by Dickens called ‘An Appeal to Fallen Women’,[21] which he signed only as ‘Your friend’. If the woman accepted the invitation, Dickens would personally interview her for admission.[22][23] All of the women were required to emigrate following their time at Urania Cottage. In research published in 2009, the families of two of these women were identified, one in Canada and one in Australia. It is estimated that about 100 women graduated between 1847 and 1859.[24]

Middle years

In late November 1851, Dickens moved into Tavistock House[25] where he would write Bleak House (1852–53), Hard Times (1854) and Little Dorrit (1857). It was here he got up the amateur theatricals which are described in Forster's Life. In 1856, his income from his writing allowed him to buy Gad's Hill Place in Higham, Kent. As a child, Dickens had walked past the house and dreamed of living in it. The area was also the scene of some of the events of Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1 and this literary connection pleased him.

In 1857, Dickens hired professional actresses for the play The Frozen Deep, which he and his protégé Wilkie Collins had written. With one of these, Ellen Ternan, Dickens formed a bond which was to last the rest of his life. He then separated from his wife, Catherine, in 1858 – divorce was still unthinkable for someone as famous as he was.

During this period, whilst pondering about giving public readings for his own profit, Dickens was approached by Great Ormond Street Hospital to help it survive its first major financial crisis through a charitable appeal. Dickens, whose philanthropy was well-known, was asked to preside by his friend, the hospital's founder Charles West. He threw himself into the task, heart and soul[26] (a little known fact is that Dickens reported anonymously in the weekly The Examiner in 1849 to help mishandled children and wrote another article to help publicise the hospital's opening in 1852).[27] On 9 February 1858, Dickens spoke at the hospital's first annual festival dinner at Freemasons' Hall and later gave a public reading of A Christmas Carol at St. Martin-in-the-Fields church hall. The events raised enough money to enable the hospital to purchase the neighbouring house, No. 48 Great Ormond Street, increasing the bed capacity from 20 to 75.[28]

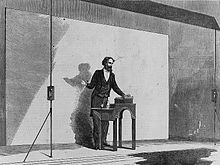

That summer of 1858, after separating from his wife,[29] Dickens undertook his first series of public readings in London for pay which ended on 22 July. After 10 days rest, he began a gruelling and ambitious tour through the English provinces, Scotland and Ireland, beginning with a performance in Clifton on 2 August and closing in Brighton, more than three months later, on 13 November. Altogether he read eighty-seven times, on some days giving both a matinée and an evening performance.[30]

Major works, A Tale of Two Cities (1859); and Great Expectations (1861) soon followed and would prove resounding successes. During this time he was also the publisher and editor of, and a major contributor to, the journals Household Words (1850–1859) and All the Year Round (1858–1870).

In early September 1860, in a field behind Gad's Hill, Dickens made a great bonfire of nearly his entire correspondence. Only those letters on business matters were spared. Since Ellen Ternan burned all of his letters as well, the dimensions of the affair between the two were unknown until the publication of Dickens and Daughter, a book about Dickens's relationship with his daughter Kate, in 1939. Kate Dickens worked with author Gladys Storey on the book prior to her death in 1929, and alleged that Dickens and Ternan had a son who died in infancy, though no contemporary evidence exists.[31] On his death, Dickens settled an annuity on Ternan which made her a financially independent woman. Claire Tomalin's book, The Invisible Woman, set out to prove that Ternan lived with Dickens secretly for the last 13 years of his life, and was subsequently turned into a play, Little Nell, by Simon Gray.

In the same period, Dickens furthered his interest in the paranormal, so much that he was one of the early members of The Ghost Club.[32]

Franklin incident

A recurring theme in Dickens's writing reflected the public's interest in Arctic exploration: the heroic friendship between explorers John Franklin and John Richardson gave the idea for A Tale of Two Cities, The Wreck of the Golden Mary and the play The Frozen Deep.[33]

After Franklin died in unexplained circumstances on an expedition to find the North West Passage, Dickens wrote a piece in Household Words defending his hero against the discovery in 1854, some four years after the search began, of evidence that Franklin's men had, in their desperation, resorted to cannibalism.[34] Without adducing any supporting evidence he speculates that, far from resorting to cannibalism amongst themselves, the members of the expedition may have been "set upon and slain by the Esquimaux ... We believe every savage to be in his heart covetous, treacherous, and cruel."[34] Although publishing in a subsequent issue of Household Words a defence of the Esquimaux, written by John Rae, one of Franklin's rescue parties, who had actually visited the scene of the supposed cannibalism, Dickens refused to alter his view.[35]

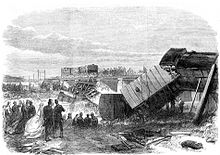

Last years

On 9 June 1865,[36] while returning from Paris with Ternan, Dickens was involved in the Staplehurst rail crash. The first seven carriages of the train plunged off a cast iron bridge under repair. The only first-class carriage to remain on the track was the one in which Dickens was travelling. Dickens tried to help the wounded and the dying before rescuers arrived. Before leaving, he remembered the unfinished manuscript for Our Mutual Friend, and he returned to his carriage to retrieve it. Typically, Dickens later used this experience as material for his short ghost story The Signal-Man in which the central character has a premonition of his own death in a rail crash. He based the story around several previous rail accidents, such as the Clayton Tunnel rail crash of 1861.

Dickens managed to avoid an appearance at the inquest, to avoid disclosing that he had been travelling with Ternan and her mother, which would have caused a scandal. Although physically unharmed, Dickens never really recovered from the trauma of the Staplehurst crash, and his normally prolific writing shrank to completing Our Mutual Friend and starting the unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Much of his time was taken up with public readings from his best-loved novels. Dickens was fascinated by the theatre as an escape from the world, and theatres and theatrical people appear in Nicholas Nickleby. The travelling shows were extremely popular. In 1866, a series of public readings were undertaken in England and Scotland. The following year saw more readings in England and Ireland.

Second visit to America

On 9 November 1867, Dickens sailed from Liverpool for his second American reading tour. Landing at Boston, he devoted the rest of the month to a round of dinners with such notables as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his American publisher James Thomas Fields. In early December, the readings began and Dickens spent the month shuttling between Boston and New York. Although he had started to suffer from what he called the "true American catarrh", he kept to a schedule that would have challenged a much younger man, even managing to squeeze in some sleighing in Central Park. In New York, he gave 22 readings at Steinway Hall between 9 December 1867 and 18 April 1868, and four at Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims between 16 and 21 January 1868. During his travels, he saw a significant change in the people and the circumstances of America. His final appearance was at a banquet the American Press held in his honour at Delmonico's on 18 April, when he promised to never denounce America again. By the end of the tour, the author could hardly manage solid food, subsisting on champagne and eggs beaten in sherry. On 23 April, he boarded his ship to return to Britain, barely escaping a Federal Tax Lien against the proceeds of his lecture tour.[18]

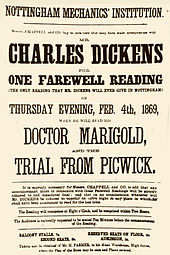

Farewell readings

Between 1868 and 1869, Dickens gave a series of "farewell readings" in England, Scotland, and Ireland, until he collapsed on 22 April 1869, at Preston in Lancashire showing symptoms of a mild stroke.[37] After further provincial readings were cancelled, he began work on his final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. In an opium den in Shadwell, he witnessed an elderly pusher known as "Opium Sal", who subsequently featured in his mystery novel.

When he had regained sufficient strength, Dickens arranged, with medical approval, for a final series of readings at least partially to make up to his sponsors what they had lost due of his illness. There were to be twelve performances, running between 11 January and 15 March 1870, the last taking place at 8:00 pm at St. James's Hall in London. Although in grave health by this time, he read A Christmas Carol and The Trial from Pickwick. On 2 May, he made his last public appearance at a Royal Academy Banquet in the presence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, paying a special tribute to the passing of his friend, illustrator Daniel Maclise.[38]

Death

On 8 June 1870, Dickens suffered another stroke at his home, after a full day's work on Edwin Drood. The next day, on 9 June, and five years to the day after the Staplehurst rail crash 9 June 1865, he died at Gad's Hill Place never having regained consciousness. Contrary to his wish to be buried at Rochester Cathedral "in an inexpensive, unostentatious, and strictly private manner", he was laid to rest in the Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey.[39] A printed epitaph circulated at the time of the funeral reads: "To the Memory of Charles Dickens (England's most popular author) who died at his residence, Higham, near Rochester, Kent, 9 June 1870, aged 58 years. He was a sympathiser with the poor, the suffering, and the oppressed; and by his death, one of England's greatest writers is lost to the world."[40] Dickens's last words, as reported in his obituary in The Times were alleged to have been:

Be natural my children. For the writer that is natural has fulfilled all the rules of art.[41]

On Sunday, 19 June 1870, five days after Dickens's interment in the Abbey, Dean Arthur Penrhyn Stanley delivered a memorial elegy, lauding "the genial and loving humorist whom we now mourn", for showing by his own example "that even in dealing with the darkest scenes and the most degraded characters, genius could still be clean, and mirth could be innocent." Pointing to the fresh flowers that adorned the novelist's grave, Stanley assured those present that "the spot would thenceforth be a sacred one with both the New World and the Old, as that of the representative of literature, not of this island only, but of all who speak our English tongue."[42]

Dickens's will stipulated that no memorial be erected to honour him. The only life-size bronze statue of Dickens, cast in 1891 by Francis Edwin Elwell, is located in Clark Park in the Spruce Hill neighbourhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the United States. The couch on which he died is preserved at the Dickens Birthplace Museum in Portsmouth.

Literary style

Dickens loved the style of the 18th century picturesque or Gothic romance novels, [citation needed] although it had already become a target for parody.[43] One "character" vividly drawn throughout his novels is London itself. From the coaching inns on the outskirts of the city to the lower reaches of the Thames, all aspects of the capital are described over the course of his body of work.

His writing style is florid and poetic, with a strong comic touch. His satires of British aristocratic snobbery—he calls one character the "Noble Refrigerator"—are often popular. Comparing orphans to stocks and shares, people to tug boats, or dinner-party guests to furniture are just some of Dickens's acclaimed flights of fancy. Many of his characters' names provide the reader with a hint as to the roles played in advancing the storyline, such as Mr. Murdstone in the novel David Copperfield, which is clearly a combination of "murder" and stony coldness. His literary style is also a mixture of fantasy and realism.

Characters

Dickens is famed for his depiction of the hardships of the working class, his intricate plots, and his sense of humour. But he is perhaps most famed for the characters he created. His novels were heralded early in his career for their ability to capture the everyday man and thus create characters to whom readers could relate. Beginning with The Pickwick Papers in 1836, Dickens wrote numerous novels, each uniquely filled with believable personalities and vivid physical descriptions. Dickens's friend and biographer, John Forster, said that Dickens made "characters real existences, not by describing them but by letting them describe themselves."[44]

Dickensian characters—especially their typically whimsical names—are among the most memorable in English literature. The likes of Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim, Jacob Marley, Bob Cratchit, Oliver Twist, The Artful Dodger, Fagin, Bill Sikes, Pip, Miss Havisham, Charles Darnay, David Copperfield, Mr. Micawber, Abel Magwitch, Daniel Quilp, Samuel Pickwick, Wackford Squeers, Uriah Heep and many others are so well known and can be believed to be living a life outside the novels that their stories have been continued by other authors. [citation needed]

The author worked closely with his illustrators supplying them with a summary of the work at the outset and thus ensuring that his characters and settings were exactly how he envisioned them.[45] He would brief the illustrator on plans for each month's instalment so that work could begin before he wrote them. Marcus Stone, illustrator of Our Mutual Friend, recalled that the author was always "ready to describe down to the minutest details the personal characteristics, and ... life-history of the creations of his fancy."[30] This close working relationship is important to readers of Dickens today. The illustrations give us a glimpse of the characters as Dickens described them. Film makers still use the illustrations as a basis for characterisation, costume, and set design.

Often these characters were based on people he knew. In a few instances Dickens based the character too closely on the original, as in the case of Harold Skimpole in Bleak House, based on Leigh Hunt, and Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield, based on his wife's dwarf chiropodist. Indeed, the acquaintances made when reading a Dickens novel are not easily forgotten. The author, Virginia Woolf, maintained that "we remodel our psychological geography when we read Dickens" as he produces "characters who exist not in detail, not accurately or exactly, but abundantly in a cluster of wild yet extraordinarily revealing remarks."[46]

Autobiographical elements

All authors might be said to incorporate autobiographical elements in their fiction, but with Dickens this is very noticeable, even though he took pains to mask what he considered his shameful, lowly past. David Copperfield is one of the most clearly autobiographical but the scenes from Bleak House of interminable court cases and legal arguments are drawn from the author's brief career as a court reporter. Dickens's own father was sent to prison for debt, and this became a common theme in many of his books, with the detailed depiction of life in the Marshalsea prison in Little Dorrit resulting from Dickens's own experiences of the institution. Childhood sweethearts in many of his books (such as Little Em'ly in David Copperfield) may have been based on Dickens's own childhood infatuation with Lucy Stroughill.[47][48] Dickens may have drawn on his childhood experiences, but he was also ashamed of them and would not reveal that this was where he gathered his realistic accounts of squalor. Very few knew the details of his early life until six years after his death when John Forster published a biography on which Dickens had collaborated.

Episodic writing

As noted above, most of Dickens's major novels were first written in monthly or weekly instalments in journals such as Master Humphrey's Clock and Household Words, later reprinted in book form. These instalments made the stories cheap, accessible and the series of regular cliff-hangers made each new episode widely anticipated. American fans even waited at the docks in New York, shouting out to the crew of an incoming ship, "Is little Nell dead?"[49][50][51] Part of Dickens's great talent was to incorporate this episodic writing style but still end up with a coherent novel at the end. The monthly numbers were illustrated by, amongst others, "Phiz" (a pseudonym for Hablot Browne). Among his best-known works are Great Expectations, David Copperfield, Oliver Twist, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, Nicholas Nickleby, The Pickwick Papers, and A Christmas Carol.

Dickens's technique of writing in monthly or weekly instalments (depending on the work) can be understood by analysing his relationship with his illustrators. The several artists who filled this role were privy to the contents and intentions of Dickens's instalments before the general public. Thus, by reading these correspondences between author and illustrator, the intentions behind Dickens's work can be better understood. These also reveal how the interests of the reader and author do not coincide. A great example of that appears in the monthly novel Oliver Twist. At one point in this work, Dickens had Oliver become embroiled in a robbery. That particular monthly instalment concludes with young Oliver being shot. Readers expected that they would be forced to wait only a month to find out the outcome of that gunshot. In fact, Dickens did not reveal what became of young Oliver in the succeeding number. Rather, the reading public was forced to wait two months to discover if the boy lived.

Another important impact of Dickens's episodic writing style resulted from his exposure to the opinions of his readers. Since Dickens did not write the chapters very far ahead of their publication, he was allowed to witness the public reaction and alter the story depending on those public reactions. A fine example of this process can be seen in his weekly serial The Old Curiosity Shop, which is a chase story. In this novel, Nell and her grandfather are fleeing the villain Quilp. The progress of the novel follows the gradual success of that pursuit. As Dickens wrote and published the weekly instalments, his friend John Forster pointed out: "You know you're going to have to kill her, don't you?" Why this end was necessary can be explained by a brief analysis of the difference between the structure of a comedy versus a tragedy. In a comedy, the action covers a sequence "You think they're going to lose, you think they're going to lose, they win". In tragedy, it is: "You think they're going to win, you think they're going to win, they lose". The dramatic conclusion of the story is implicit throughout the novel. So, as Dickens wrote the novel in the form of a tragedy, the sad outcome of the novel was a foregone conclusion. If he had not caused his heroine to lose, he would not have completed his dramatic structure. Dickens admitted that his friend Forster was right and, in the end, Nell died.[52]

Social commentary

Dickens's novels were, among other things, works of social commentary. He was a fierce critic of the poverty and social stratification of Victorian society. Dickens's second novel, Oliver Twist (1839), shocked readers with its images of poverty and crime and was responsible for the clearing of the actual London slum, Jacob's Island, that was the basis of the story. In addition, with the character of the tragic prostitute, Nancy, Dickens "humanised" such women for the reading public; women who were regarded as "unfortunates", inherently immoral casualties of the Victorian class/economic system. Bleak House and Little Dorrit elaborated expansive critiques of the Victorian institutional apparatus: the interminable lawsuits of the Court of Chancery that destroyed people's lives in Bleak House and a dual attack in Little Dorrit on inefficient, corrupt patent offices and unregulated market speculation.

Literary techniques

Dickens is often described as using 'idealised' characters and highly sentimental scenes to contrast with his caricatures and the ugly social truths he reveals. The story of Nell Trent in The Old Curiosity Shop (1841) was received as incredibly moving by contemporary readers but viewed as ludicrously sentimental by Oscar Wilde. "You would need to have a heart of stone", he declared in one of his famous witticisms, "not to laugh at the death of little Nell."[53] (although her death actually takes place off-stage). In 1903 G. K. Chesterton said, "It is not the death of little Nell, but the life of little Nell, that I object to."[54]

In Oliver Twist Dickens provides readers with an idealised portrait of a boy so inherently and unrealistically 'good' that his values are never subverted by either brutal orphanages or coerced involvement in a gang of young pickpockets. While later novels also centre on idealised characters (Esther Summerson in Bleak House and Amy Dorrit in Little Dorrit), this idealism serves only to highlight Dickens's goal of poignant social commentary. Many of his novels are concerned with social realism, focusing on mechanisms of social control that direct people's lives (for instance, factory networks in Hard Times and hypocritical exclusionary class codes in Our Mutual Friend).[citation needed]Dickens also employs incredible coincidences (e.g., Oliver Twist turns out to be the lost nephew of the upper class family that randomly rescues him from the dangers of the pickpocket group). Such coincidences are a staple of eighteenth century picaresque novels such as Henry Fielding's Tom Jones that Dickens enjoyed so much. But, to Dickens, these were not just plot devices but an index of the humanism that led him to believe that good wins out in the end and often in unexpected ways.[citation needed]

Legacy

A well-known personality, his novels proved immensely popular during his lifetime. His first full novel, The Pickwick Papers (1837), brought him immediate fame, and this success continued throughout his career. Although rarely departing greatly from his typical "Dickensian" method of always attempting to write a great "story" in a somewhat conventional manner (the dual narrators of Bleak House constitute a notable exception), he experimented with varied themes, characterisations, and genres. Some of these experiments achieved more popularity than others, and the public's taste and appreciation of his many works have varied over time. Usually keen to give his readers what they wanted, the monthly or weekly publication of his works in episodes meant that the books could change as the story proceeded at the whim of the public. Good examples of this are the American episodes in Martin Chuzzlewit which Dickens included in response to lower-than-normal sales of the earlier chapters. Dickens continues to be one of the best known and most read of English authors, and his works have never gone out of print.[3] At least 180 motion pictures and TV adaptations based on Dickens's works help confirm his success.[55] Many of his works were adapted for the stage during his own lifetime and as early as 1913 a silent film of The Pickwick Papers was made. His characters were often so memorable that they took on a life of their own outside his books. Gamp became a slang expression for an umbrella from the character Mrs. Gamp and Pickwickian, Pecksniffian, and Gradgrind all entered dictionaries due to Dickens's original portraits of such characters who were quixotic, hypocritical, or emotionlessly logical. Sam Weller, the carefree and irreverent valet of The Pickwick Papers, was an early superstar, perhaps better known than his author at first. It is likely that A Christmas Carol stands as his best-known story, with new adaptations almost every year. It is also the most-filmed of Dickens's stories, with many versions dating from the early years of cinema. This simple morality tale with both pathos and its theme of redemption, sums up (for many) the true meaning of Christmas. Indeed, it eclipses all other Yuletide stories in not only popularity, but in adding archetypal figures (Scrooge, Tiny Tim, the Christmas ghosts) to the Western cultural consciousness. A prominent phrase from the tale, 'Merry Christmas', was popularised following the appearance of the story.[56] The term Scrooge became a synonym for miser, with 'Bah! Humbug!' dismissive of the festive spirit.[57] Novelist William Makepeace Thackeray called the book "a national benefit, and to every man and woman who reads it a personal kindness".[58] Some historians claim the book significantly redefined the "spirit" and importance of Christmas,[59][60] and initiated a rebirth of seasonal merriment after Puritan authorities in 17th century England and America suppressed pagan rituals associated with the holiday.[61] According to the historian Ronald Hutton, the current state of the observance of Christmas is largely the result of a mid-Victorian revival of the holiday spearheaded by A Christmas Carol. Dickens sought to construct Christmas as a family-centred festival of generosity, in contrast to the community-based and church-centred observations, the observance of which had dwindled during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[62] Superimposing his secular vision of the holiday, Dickens influenced many aspects of Christmas that are celebrated today among Western nations, such as family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, games, and a festive generosity of spirit.[63] A Christmas Carol rejuvenated his career as a renowned author. A Tale of Two Cities is Dickens best selling novel. Since its inaugural publication in 1859, the novel has sold over 200 million copies, and is among the most famous works of fiction.[64]

At a time when Britain was the major economic and political power of the world, Dickens highlighted the life of the forgotten poor and disadvantaged within society. Through his journalism he campaigned on specific issues—such as sanitation and the workhouse—but his fiction probably demonstrated its greatest prowess in changing public opinion in regard to class inequalities. He often depicted the exploitation and repression of the poor and condemned the public officials and institutions that not only allowed such abuses to exist, but flourished as a result. His most strident indictment of this condition is in Hard Times (1854), Dickens's only novel-length treatment of the industrial working class. In this work, he uses both vitriol and satire to illustrate how this marginalised social stratum was termed "Hands" by the factory owners; that is, not really "people" but rather only appendages of the machines that they operated. His writings inspired others, in particular journalists and political figures, to address such problems of class oppression. For example, the prison scenes in The Pickwick Papers are claimed to have been influential in having the Fleet Prison shut down. As Karl Marx said, Dickens, and the other novelists of Victorian England, "...issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together...".[65] The exceptional popularity of his novels, even those with socially oppositional themes (Bleak House, 1853; Little Dorrit, 1857; Our Mutual Friend, 1865) underscored not only his almost preternatural ability to create compelling storylines and unforgettable characters, but also ensured that the Victorian public confronted issues of social justice that had commonly been ignored.

His fiction, with often vivid descriptions of life in nineteenth century England, has inaccurately and anachronistically come to symbolise on a global level Victorian society (1837 – 1901) as uniformly "Dickensian", when in fact, his novels' time span spanned from the 1770s to the 1860s. In the decade following his death in 1870, a more intense degree of socially and philosophically pessimistic perspectives invested British fiction; such themes stood in marked contrast to the religious faith that ultimately held together even the bleakest of Dickens's novels. Dickens clearly influenced later Victorian novelists such as Thomas Hardy and George Gissing; their works display a greater willingness to confront and challenge the Victorian institution of religion. They also portray characters caught up by social forces (primarily via lower-class conditions), but they usually steered them to tragic ends beyond their control.

Novelists continue to be influenced by his books; for instance, such disparate current writers as Anne Rice, Tom Wolfe, and John Irving evidence direct Dickensian connections. Humorist James Finn Garner even wrote a tongue-in-cheek "politically correct" version of A Christmas Carol, and other affectionate parodies include the Radio 4 comedy Bleak Expectations. Matthew Pearl's novel The Last Dickens is a thriller about how Charles Dickens would have ended The Mystery of Edwin Drood. In the UK survey entitled The Big Read carried out by the BBC in 2003, five of Dickens' books were named in the Top 100, featuring alongside Terry Pratchett with the most.[66]

Although Dickens's life has been the subject of at least two TV miniseries, a television film The Great Inimitable Mr. Dickens in which he was portrayed by Anthony Hopkins, and two famous one-man shows, he has never been the subject of a Hollywood big screen biography.[67]

Claims of anti-Semitism and racism

Paul Vallely writes in The Independent that Dickens's Fagin in Oliver Twist —the Jew who runs a school in London for child pickpockets—is widely seen as one of the most grotesque Jews in English literature, and the most vivid of Dickens's 989 characters.[68]

The mud lay thick upon the stones, and a black mist hung over the streets; the rain fell sluggishly down, and everything felt cold and clammy to the touch. It seemed just the night when it befitted such a being as the Jew to be abroad. As he glided stealthily along, creeping beneath the shelter of the walls and doorways, the hideous old man seemed like some loathsome reptile, engendered in the slime and darkness through which he moved, crawling forth by night in search of some rich offal for a meal.[69]

The character is thought to have been partly based on Ikey Solomon, a 19th century Jewish criminal in London, who was interviewed by Dickens during the latter's time as a journalist.[70] Nadia Valdman, who writes about the portrayal of Jews in literature, argues that Fagin's representation was drawn from the image of the Jew as inherently evil, that the imagery associated him with the Devil, and with beasts.[71]

The novel refers to Fagin 257 times in the first 38 chapters as "the Jew", while the ethnicity or religion of the other characters is rarely mentioned.[68] In 1854, the Jewish Chronicle asked why "Jews alone should be excluded from the 'sympathizing heart' of this great author and powerful friend of the oppressed." Eliza Davis, whose husband had purchased Dickens's home in 1860 when he had put it up for sale, wrote to Dickens in protest at his portrayal of Fagin, arguing that he had "encouraged a vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew", and that he had done a great wrong to the Jewish people. Dickens had described her husband at the time of the sale as a "Jewish moneylender", though also someone he came to know as an honest gentleman.

Surprisingly, Dickens took her complaint seriously. He halted the printing of Oliver Twist, and changed the text for the parts of the book that had not been set, which is why Fagin is called "the Jew" 257 times in the first 38 chapters, but barely at all in the next 179 references to him. In his novel, Our Mutual Friend, he created the character of Riah (meaning "friend" in Hebrew), whose goodness, Vallely writes, is almost as complete as Fagin's evil. Riah says in the novel: "Men say, 'This is a bad Greek, but there are good Greeks. This is a bad Turk, but there are good Turks.' Not so with the Jews ... they take the worst of us as samples of the best ..." Davis sent Dickens a copy of the Hebrew bible in gratitude.[68]

Dickens's attitudes towards blacks were also complex, although he fiercely opposed the inhumanity of slavery in the United States, and expressed a desire for African American emancipation. In American Notes, he includes a comic episode with a black coach driver, presenting a grotesque description focused on the man's dark complexion and way of movement, which to Dickens amounts to an "insane imitation of an English coachman".[72] In 1868, alluding to the then poor intellectual condition of the black population in America, Dickens railed against "the mechanical absurdity of giving these people votes", which "at any rate at present, would glare out of every roll of their eyes, chuckle in their mouths, and bump in their heads."[72]

In The Perils of Certain English Prisoners Dickens offers an allegory of the Indian Mutiny, where the "native Sambo", a paradigm of the Indian mutineers,[73] is a "double-dyed traitor, and a most infernal villain" who takes part in a massacre of women and children, in an allusion to the Cawnpore Massacre.[74] Dickens was much incensed by the massacre, in which over a hundred English prisoners, most of them women and children, were killed, and on 4 October 1857 wrote in a private letter to Baroness Burdett-Coutts: "I wish I were the Commander in Chief in India. ... I should do my utmost to exterminate the Race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested ... proceeding, with all convenient dispatch and merciful swiftness of execution, to blot it out of mankind and raze it off the face of the earth."[75][76]

Perils greatly influenced the cultural reaction from English writers to the mutiny, by attributing guilt so as to portray the British as victims, and the Indians as villains.[73] Wilkie Collins, who co-wrote Perils, deviates from Dickens's view, writing the second chapter from a different perspective which, quoting poet Jaya Mehta, was "parodying British racism, instead of promoting it".[77] Contemporary literary critic Arthur Quiller-Couch praised Dickens for eschewing any real-life depiction of the incident, for fear of inflaming his "raging mad" readership further, in favour of a romantic story "empty of racial or propagandist hatred".[78] A modern inference is that it was his son's position in India, there on military service, at the mercy of inept imperial leaders who misunderstood conquered people, that may have influenced his reluctance to set Perils in India, for fear that his criticism may antagonise the son's superiors.[79]

Names: 'Dickens' and 'Boz'

Charles Dickens had, as a contemporary critic put it, a "queer name".[80] The name Dickens was used in interjective exclamations like "What the Dickens!" as a substitute for "devil". It was recorded in the OED as originating from Shakespeare's The Merry Wives of Windsor. It was also used in the phrase "to play the Dickens" in the meaning "to play havoc/mischief".[81]

'Boz' was Dickens' occasional pen-name, but was a familiar name in the Dickens household long before Charles became a famous author. It was actually taken from his youngest brother Augustus Dickens' family nickname 'Moses', given to him in honour of one of the brothers in The Vicar of Wakefield (one of the most widely read novels during the early 19th century). When playfully pronounced through the nose 'Moses' became 'Boses', and was later shortened to 'Boz' – pronounced through the nose with a long vowel 'o'.[82]

Siblings

- Frances (Fanny) Elizabeth Dickens 1810–1848

- Letitia Dickens 1816–1893

- Harriet Dickens 1819–1824

- Frederick Dickens

- Alfred Lamert Dickens

- Augustus Newnham Dickens

Adaptations of readings

There have been several performances of Dickens readings by Emlyn Williams, Bransby Williams, Clive Francis performing the John Mortimer adaptation of A Christmas Carol and also Simon Callow in the Mystery of Charles Dickens by Peter Ackroyd. Entertainer Mike Randall re-enacts Dickens's readings (in character as Dickens) for a series of shows known as "Charles Dickens Presents A Christmas Carol," primarily in his home region in Western New York.

Museums and festivals

There are museums and festivals celebrating Dickens's life and works in many of the towns with which he was associated.

- The Charles Dickens Museum, in Doughty Street, Holborn is the only one of Dickens's London homes to survive. He lived there only two years but in that time wrote The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby. It contains a major collection of manuscripts, original furniture and memorabilia.

- Charles Dickens Birthplace Museum in Portsmouth is the house in which Dickens was born. It has been re-furnished in the likely style of 1812 and contains Dickens memorabilia.

- The Dickens House Museum in Broadstairs, Kent is the house of Miss Mary Pearson Strong, the basis for Miss Betsey Trotwood in David Copperfield. It is visible across the bay from the original Bleak House (also a museum until 2005) where David Copperfield was written. The museum contains memorabilia, general Victoriana and some of Dickens's letters. Broadstairs has held a Dickens Festival annually since 1937.

- The Charles Dickens Centre in Eastgate House, Rochester, closed in 2004, but the garden containing the author's Swiss chalet is still open. The 16th century house, which appeared as Westgate House in The Pickwick Papers and the Nun's House in Edwin Drood, is now used as a wedding venue.[83] The city's annual Dickens Festival (summer) and Dickensian Christmas celebrations continue unaffected. Summer Dickens is held at the end of May or in the first few days of June, it commences with an invitation only ball on the Thursday and then continues with street entertainment, and many costumed characters, on the Friday, Saturday and Sunday. Christmas Dickens is the first weekend in December- Saturday and Sunday only.

- Dickens World themed attraction, covering 71,500 square feet (6,643 m2), and including a cinema and restaurants, opened in Chatham on 25 May 2007.[84] It stands on a small part of the site of the former naval dockyard where Dickens's father had once worked in the Navy Pay Office.

- To celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Dickens in 2012 the Museum of London hosts the UK's first major exhibition on the author for 40 years. Dickens and London opens on 9 December 2011 and is on until 10 June 2012.

Dickens festivals are also held across the world. Four notable ones in the United States are:

- The Riverside Dickens Festival in Riverside, California, includes literary studies as well as entertainments.

- The Great Dickens Christmas Fair has been held in San Francisco, California, since the 1970s. During the four or five weekends before Christmas, over 500 costumed performers mingle with and entertain thousands of visitors amidst the recreated full-scale blocks of Dickensian London in over 90,000 square feet (8,000 m2) of public area. This is the oldest, largest, and most successful of the modern Dickens festivals outside England. Many (including the Martin Harris who acts in the Rochester festival and flies out from London to play Scrooge every year in SF) say it is the most impressive in the world.[85]

- Dickens on The Strand in Galveston, Texas, is a holiday festival held on the first weekend in December since 1974, where bobbies, Beefeaters and the "Queen" herself are on hand to recreate the Victorian London of Charles Dickens. Many festival volunteers and attendees dress in Victorian attire and bring the world of Dickens to life.

- The Greater Port Jefferson-Northern Brookhaven Arts Council[86] holds a Dickens Festival in the Village of Port Jefferson, New York each year. In 2009, the Dickens Festival was 4 December, 5 and 6 December. It includes many events, along with a troupe of street performers who bring an authentic Dickensian atmosphere to the town.

Other memorials

Charles Dickens was commemorated on the Series E £10 note issued by the Bank of England which was in circulation in the UK between 1992 and 2003. Dickens appeared on the reverse of the note accompanied by a scene from The Pickwick Papers.[87]

Notable works

Charles Dickens published over a dozen major novels, a large number of short stories (including a number of Christmas-themed stories), a handful of plays, and several non-fiction books. Dickens's novels were initially serialised in weekly and monthly magazines, then reprinted in standard book formats.

Novels

|

|

Short story collections

- Sketches by Boz (1836)

- The Mudfog Papers (1837) in Bentley's Miscellany magazine

- Reprinted Pieces (1861)

- The Uncommercial Traveller (1860–1869)

|

Christmas numbers of Household Words magazine:

|

Christmas numbers of All the Year Round magazine:

|

Selected non-fiction, poetry, and plays

|

|

Notes

- ^ "Victorian squalor and hi-tech gadgetry: Dickens World to open in England", The New York Times, 23 May 2007.

- ^ Stone, Harry. Dickens' Working Notes for His Novels. Chicago, 1987.

- ^ a b Swift, Simon. "What the Dickens?", The Guardian, 18 April 2007.

- ^ Henry James, "Our Mutual Friend", The Nation, 21 December 1865.

- ^ "John Forster, ''The Life of Charles Dickens'', Book 1, Chapter 2". Lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ Jordan, John (2001). "Chronology". The Cambridge companion to Charles Dickens. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. xvi. ISBN 0-521-66964-2.

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, Una (1945). "The Family Background". Charles Dickens 1812–1870. London: Chatto and Windus. p. 11. ISBN 0897607627.

- ^ a b Project Gutenberg's Life of Charles Dickens (James R. Osgood & Company, 1875), by John Forster, Volume I, Chapter II, accessed 2 August 2008

- ^ a b c Angus Wilson. The World of Charles Dickens. London: Secker and Warburg, 1970. ISBN 0140034889. p.53

- ^ ""Charles Dickens", accessed 15 November 2007". Enotes.com. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ Pope-Hennessy (1945: 18)

- ^ RE: Cremains / Ravens

- ^ Myheritage.com Dickens Family Tree website

- ^ Victorianweb.org – Mary Scott Hogarth, 1820–1837: Dickens's Beloved Sister-in-Law and Inspiration

- ^ Bowen, John (2004). "Dickens's Black Atlantic". Dickens and empire: discourses of class, race and colonialism in the works of Charles Dickens. Farnham, England: Ashgate. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7546-3412-6.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Dickens, Charles (1842). "Slavery". American Notes for General Circulation. London: Chapman and Hall. pp. 94–100. ISBN 0460876856. OCLC 41667089.

- ^ Dickens (1842: 53–55

- ^ a b Kenneth T. Jackson: The Encyclopedia of New York City: The New York Historical Society; Yale University Press; 1995. P. 333.

- ^ Jones, Richard (2004). Walking Dickensian London. London: New Holland. p. 7. ISBN 9781843304838.

- ^ "Charles Dickens". Uua.org. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ "'An Appeal to Fallen Women'" (PDF). Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ^ Gavin Adams, Adams Hamilton Literary and Historical Manuscripts, 2009

- ^ 'The Letters of Charles Dickens', Pilgrim Edition, Vol. VII, p.527.

- ^ Jenny Hartley, Charles Dickens and The House of Fallen Women, (Methuen, 2009).

- ^ "Tavistock House | British History Online". British-history.ac.uk. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ Charles Dickens: Family History edited by Norman Page, University of Nottingham

- ^ "Charles Dickens' Work to Help Establish Great Ormond Street Hospital, London." by Sir Howard Markel, The Lancet, 21 Aug, p 673.

- ^ Sofii.org

- ^ Household Words 12 June 1858

- ^ a b The New York Public Library, Berg Collection of English and American Literature

- ^ Tomalin (1995). "The Invisible Woman: The Story of Charles Dickens and Nelly Ternan" (PDF). Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ^ "History of the Ghost Club". Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Glancy, Ruth F (2006). "The Frozen Deep and other Biographical Influences". Charles Dickens's A Tale Of Two Cities: A Sourcebook. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 0415287596.

- ^ a b Dickens, Charles (2 December 1854). "The Lost Arctic Voyagers". Household Words: A Weekly Journal. 10 (245). London: Charles Dickens: 361 et sec. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ Rae, John (30 December 1854). "Dr Rae's report". Household Words: A Weekly Journal. 10 (249). London: Charles Dickens: 457–458. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- ^ Slater (2004)

- ^ "New York Public Library / The Great Magician Vanishes". Nypl.org. Retrieved 24 July 2009. [dead link]

- ^ The British Academy/The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens: Volume 12: 1868–1870

- ^ Staff writers (2007). "Charles Dickens". History. The Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

A small stone with a simple inscription marks the grave of this famous English novelist in Poets' Corner: 'Charles Dickens Born 7 February 1812 Died 9 June 1870'

- ^ "Printed at J. H. Woodley's Funeral Tablet Office, 30 Fore Street, City, London." and reproduced on page 4, A Christmas Carol Study Guide by Patti Kirkpatrick, Education Department, Dallas Theater Center.

- ^ Green, J. (1979), Famous Last Words, Enderby, Leicester, Silverdale Books, ISBN 1-85626-577-9.

- ^ New York Public Library, Berg Collection

- ^ Austen, Jane. Northanger Abbey.

- ^ The Life of Charles Dickens (first published 1872–1874) by John Forster

- ^ Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators by Jane R. Cohen. Ohio State University Press

- ^ The Essays of Virginia Woolf ed. by Andrew McNellie. Hogarth Press 1986

- ^ Everybody in Dickens by George Newlin

- ^ Dickens and women by Michael Slater

- ^ HP-Time.com;Christopher Porterfield (28 December 1970). "Boz Will Be Boz – TIME". TIME<!. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "A Dickens of a fuss – theage.com.au". The Age. Australia. 29 June 2003. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ McGrath, Charles (2 July 2006). "And They All Died Happily Ever After". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Dickens, Charles. Harry Stone. Dickens' working notes for his novels. University of Chicago Press ISBN 0226145905

- ^ In conversation with Ada Leverson. Quoted in Richard Ellmann, Oscar Wilde (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988), p. 469.

- ^ G. K. Chesterton, Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens, Chapter 6: Curiosity Shop

- ^ Charles Dickens as writer at IMDb accessdate 2 June 2009

- ^ Robertson Cochrane. Wordplay: origins, meanings, and usage of the English language. p.126 University of Toronto Press, 1996 ISBN 0802077528

- ^ Joe L. Wheeler. Christmas in my heart, Volume 10. p.97. Review and Herald Pub Assoc, 2001. ISBN 0828016224

- ^ excerpt read by William Makepeace Thackeray, New York City (1852)

- ^ Michael Patrick Hearn. The Annotated Christmas Carol. W.W. Norton and Co. ISBN 0-393-05158-7

- ^ Les Standiford. The Man Who Invented Christmas: How Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol Rescued His Career and Revived Our Holiday Spirits, Crown, 2008. ISBN 978-0307405784

- ^ Richard Michael Kelly. A Christmas Carol. Broadview Press, 2003.

- ^ Ronald Hutton; Stations of the Sun: The Ritual Year in England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-285448-8.

- ^ Richard Michael Kelly (ed.) (2003), A Christmas Carol.pp.9,12 Broadview Literary Texts, New York: Broadview Press ISBN 1551114763

- ^ Broadway.com on A Tale of Two Cities: "Since its inaugural publication on 30 August 1859, A Tale of Two Cities has sold over 200 million copies in several languages, making it one of the most famous books in the history of fictional literature." (24 March 2008)

- ^ Marx, Karl (1 August 1854). "The English Middle Classes". New York Tribune. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- ^ The Big Read: Top 100 Books BBC Retrieved 2 April 2011

- ^ Pointer, Michael (1996) Charles Dickens on the screen: the film, television, and video adaptations p.202. Scarecrow Press, 1996

- ^ a b c Vallely, Paul. Dickens' greatest villain: The faces of Fagin, 7 October 2005.

- ^ Oliver Twist, Hurd and Houghton, 1867, chapter 19, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Rutland, Suzanne D. The Jews in Australia. Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 19. ISBN 9780521612852; Newey, Vincent. The Scriptures of Charles Dickens.

- ^ Valdman, Nadia. Antisemitism, A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution. ISBN 1-85109-439-3

- ^ a b Grace Moore (28 November 2004). Dickens and empire: discourses of class, race and colonialism in the works of Charles Dickens. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 56. ISBN 9780754634126. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ a b Stewart, Nicholas. ""The Perils of Certain English Prisoners": Dickens' Defensive Fantasy of Imperial Stability". School of English, Queens University of Belfast. Retrieved 2009, 22 September.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pionke, Albert D. (2004). Plots of opportunity: Representing conspiracy in Victorian England. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press. p. 91. ISBN 9780814209486.

- ^ Letters of Charles Dickens volume 8 1856–58 Clarendon Press

- ^ Schenker, Peter (1989). An Anthology of Chartist poetry: poetry of the British working class, 1830s – 1850s. p. 353. ISBN 9780838633458.

- ^ Harrison, Kimberly (2006). Victorian sensations: essays on a scandalous genre By Kimberly Harrison, Richard Fantina. p. 227. ISBN 9780814210314.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Quiller-Couch, Arthur (1925). Charles Dickens and Other Victorians. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–11. OCLC 215059500.

- ^ Allingham, Philip V. (12 December 2005). "The Imperial Context of "The Perils of Certain English Prisoners" (1857) by Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins". The Victoria Web. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Unnamed writer (January 1849). "The Haunted Man review". Macphail's Edinburgh Ecclesiastical Journal. vi. Edinburgh: 423.

Mr Dickens, as if in revenge for his own queer name, does bestow still queerer ones upon his fictitious creations.

- ^ John Bowen (2000) Other Dickens: Pickwick to Chuzzlewit, ISBN 0199261407, p. 36

- ^ "Augustus Dickens" in The Chicago Herald, 19 February 1895

- ^ "Medway Council – Eastgate House". Medway.gov.uk. Retrieved 24 July 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Hart, Christopher (20 May 2007). "What, the Dickens World?". The Sunday Times. UK. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- ^ > The Great Dickens Christmas Fair San Francisco

- ^ The Greater Port Jefferson-Northern Brookhaven Arts Counci

- ^ "Withdrawn banknotes reference guide". Bank of England. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ Serial publication dates from Chronology of Novels by E. D. H. Johnson, Holmes Professor of Belles Lettres, Princeton University. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

References

- A Charles Dickens Devotional. Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2011. ISBN 978-1-4003-1954-1.

- Ackroyd, Peter, Dickens, (2002), Vintage, ISBN 0099437090

- Drabble, Margaret (ed.), The Oxford Companion to English Literature, (1997), Oxford University Press

- Glavin, John. (ed.) Dickens on Screen,(2003), New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kaplan, Fred. Dickens: A Biography William Morros, 1988

- Lewis, Peter R. Disaster on the Dee: Robert Stephenson's Nemesis of 1847, Tempus (2007) for a discussion of the Staplehurst accident, and its influence on Dickens.

- Meckier, Jerome. Innocent Abroad: Charles Dickens' American Engagements University Press of Kentucky, 1990

- Moss, Sidney P. Charles Dickens' Quarrel with America (New York: Whitson, 1984).

- Patten, Robert L. (ed.) The Pickwick Papers (Introduction), (1978), Penguin Books.

- Slater, Michael. "Dickens, Charles John Huffam (1812 – 1870)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004

- Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing, 2009 New Haven/London: Yale University Press ISBN 978-0-300-11207-8 [1]

Further reading

- Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert, "Becoming Dickens 'The Invention of a Novelist'", London: Harvard University Press, 2011

- Johnson, Edgar, Charles Dickens: his tragedy and triumph, New York : Simon and Schuster, 1952. In two volumes.

- Tomalin, Claire, Charles Dickens: A Life, Penguin Press HC, The, 2011.

External links

Works

- Works by Charles Dickens at Project Gutenberg, HTML and plain text versions.

- Works by or about Charles Dickens at Internet Archive and Google Books. Scanned books.

- Works by Charles Dickens at EveryAuthor, HTML versions.

- Works by Charles Dickens at Dickens Literature, HTML versions.

- Works by Charles Dickens at Penn State University Electronic Classics Series, PDF versions.

- Template:Worldcat id