Organoselenium chemistry

Organoselenium chemistry is the science exploring the properties and reactivity of organoselenium compounds, chemical compounds containing carbon-to-selenium chemical bonds.[1][2][3] Selenium belongs with oxygen and sulfur to the group 16 elements or chalcogens, and similarities in chemistry are to be expected. Organoselenium compounds are found at trace levels in ambient waters, soils and sediments.[4]

Selenium can exist with oxidation state −2, +2, +4, +6. Se(II) is the dominant form in organoselenium chemistry. Down the group 16 column, the bond strength becomes increasingly weaker (234 kJ/mol for the C−Se bond and 272 kJ/mol for the C−S bond) and the bond lengths longer (C−Se 198 pm, C−S 181 pm and C−O 141 pm). Selenium compounds are more nucleophilic than the corresponding sulfur compounds and also more acidic. The pKa values of XH2 are 16 for oxygen, 7 for sulfur and 3.8 for selenium. In contrast to sulfoxides, the corresponding selenoxides are unstable in the presence of β-protons and this property is utilized in many organic reactions of selenium, notably in selenoxide oxidations and in selenoxide eliminations.

The first organoselenium compound to be isolated was diethyl selenide in 1836.[5][6]

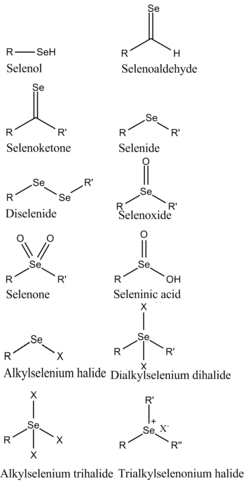

Structural classification of organoselenium compounds

[edit]

- Selenols (R−SeH) are the selenium equivalents of alcohols and thiols. These compounds are relatively unstable and generally have an unpleasant smell. Benzeneselenol (also called selenophenol or PhSeH) is more acidic (pKa 5.9) than thiophenol (pKa 6.5) and also oxidizes more readily to the diselenide. Selenophenol is prepared by reduction of diphenyldiselenide.[7]

- Diselenides (R−Se−Se−R) are the selenium equivalents of peroxides and disulfides. They are useful shelf-stable precursors to more reactive organoselenium reagents such as selenols and selanyl halides. Best known in organic chemistry is diphenyldiselenide, prepared from phenylmagnesium bromide and selenium followed by oxidation of the product PhSeMgBr.[8]

- Selanyl halides (R−Se−Cl, R−Se−Br) are prepared by halogenation of diselenides. Bromination of diphenyldiselenide gives phenylselanyl bromide (PhSeBr). These compounds are sources of "PhSe+".

- Selenides (R−Se−R), also called selenoethers, are the selenium equivalents of ethers and sulfides. One example is dimethylselenide ((CH3)2Se). These are the most prevalent organoselenium compounds. Symmetrical selenides are usually prepared by alkylation of alkali metal selenide salts, e.g. sodium selenide. Unsymmetrical selenides are prepared by alkylation of selenoates. These compounds typically react as nucleophiles, e.g. with alkyl halides (R'−X) to give selenonium salts [RR'R"Se]+X−. Divalent selenium can also interact with soft heteroatoms to form hypervalent selenium centers.[6] They also react in some circumstances as electrophiles, e.g. with organolithium reagents (R'Li) to the ate complex R'RRSe−Li+.

- Selenoxides (R−Se(=O)−R) are the selenium equivalents of sulfoxides. Most are unstable, undergoing the selenoxide elimination, but can be notionally oxidized to selenones R−Se(=O)2−R, the selenium analogues of sulfones.

- Selenenic acid (R−Se−OH) are intermediates in the oxidation of selenols. They occur in some selenoenzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase.

- Seleninic acids (R−Se(=O)−OH) are analogues of sulfinic acids.

- Selenonic acids (R−Se(=O)2−OH) are analogues of sulfonic acids.

- Peroxyseleninic acids (R−Se(=O)−OOH) catalyse epoxidation reactions and Baeyer–Villiger oxidations.

- Selenuranes are hypervalent organoselenium compounds, formally derived from the tetrahalides such as SeCl4. Examples are of the type Ar−SeCl3.[9] The chlorides are obtained by chlorination of the selenenyl chloride.

- Seleniranes are three-membered rings (the parent compound is selenirane or selenacyclobutane C2H4Se) related to thiiranes but, unlike thiiranes, seleniranes are kinetically unstable, extruding selenium directly (without oxidation) to form alkenes. This property has been utilized in synthetic organic chemistry.[10]

- Selones (R2C=Se) are the selenium analogues of ketones. They are rare due to their tendency to oligomerize.[11] Diselenobenzoquinone is stable as a metal complex.[12] Selenourea is an example of a stable compound containing a C=Se bond.

- Thioselenides (R−Se−S−R), compounds with selenium(II)–sulfur(II) bonds, analogous to disulfides.

Organoselenium compounds in nature

[edit]Selenium, in the form of organoselenium compounds, is an essential micronutrient whose absence from the diet causes cardiac muscle and skeletal dysfunction. Organoselenium compounds are required for cellular defense against oxidative damage and for the correct functioning of the immune system. They may also play a role in prevention of premature aging and cancer. The source of Se used in biosynthesis is selenophosphate.

Glutathione oxidase is an enzyme with a selenol at its active site. Organoselenium compounds have been found in higher plants. For example, upon analysis of garlic using the technique of high-performance liquid chromatography combined with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (HPLC-ICP-MS), it was found that γ-glutamyl-Se-methylselenocysteine was the major Se-containing component, along with lesser amounts of Se-methylselenocysteine. Trace quantities of dimethyl selenide and allyl methyl selenide are found in human breath after consuming raw garlic.[13]

Selenocysteine and selenomethionine

[edit]Selenocysteine, called the twenty-first amino acid, is essential for ribosome-directed protein synthesis in some organisms.[14] More than 25 selenium-containing proteins (selenoproteins) are now known.[15] Most selenium-dependent enzymes contain selenocysteine, which is related to cysteine analog but with selenium replacing sulfur. This amino acid is encoded in a special manner by DNA. Selenosulfides are also proposed as biochemical intermediates.

Selenomethionine is a selenide-containing amino acid that also occurs naturally, but is generated by post-transcriptional modification.

Organoselenium chemistry in organic synthesis

[edit]Organoselenium compounds are specialized but useful collection of reagents useful in organic synthesis, although they are generally excluded from processes useful to pharmaceuticals owing to regulatory issues. Their usefulness hinges on certain attributes, including

- the weakness of the C−Se bond and

- the easy oxidation of divalent selenium compounds.

Vinylic selenides

[edit]Vinylic selenides are organoselenium compounds that play a role in organic synthesis, especially in the development of convenient stereoselective routes to functionalized alkenes.[16] Although various methods are mentioned for the preparation of vinylic selenides, a more useful procedure has centered on the nucleophilic or electrophilic organoselenium addition to terminal or internal alkynes.[17][18][19][20] For example, the nucleophilic addition of selenophenol to alkynes affords, preferentially, the Z-vinylic selenides after longer reaction times at room temperature. The reaction is faster at a high temperature; however, the mixture of Z- and E-vinylic selenides was obtained in an almost 1:1 ratio.[21] On the other hand, the adducts depend on the nature of the substituents at the triple bond. Conversely, vinylic selenides can be prepared by palladium-catalyzed hydroselenation of alkynes to afford the Markovnikov adduct in good yields. There are some limitations associated with the methodologies to prepare vinylic selenides illustrated above; the procedures described employ diorganoyl diselenides or selenophenol as starting materials, which are volatile and unstable and have an unpleasant odor. Also, the preparation of these compounds is complex.

Selenoxide oxidations

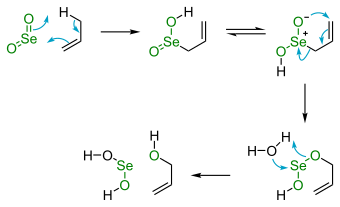

[edit]Selenium dioxide is useful in organic oxidation. Specifically, SeO2 will convert an allylic methylene group into the corresponding alcohol. A number of other reagents bring about this reaction.

In terms of reaction mechanism, SeO2 and the allylic substrate react via pericyclic process beginning with an ene reaction that activates the C−H bond. The second step is a [2,3] sigmatropic reaction. Oxidations involving selenium dioxide are often carried out with catalytic amounts of the selenium compound and in presence of a sacrificial catalyst or co-oxidant such as hydrogen peroxide.

SeO2-based oxidations sometimes afford carbonyl compounds such as ketones,[22] β-Pinene[23] and cyclohexanone oxidation to 1,2-cyclohexanedione.[24] Oxidation of ketones having α-methylene groups affords diketones. This type of oxidation with selenium oxide is called Riley oxidation.[25]

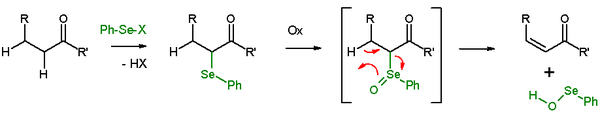

Selenoxide eliminations

[edit]In presence of a β-hydrogen, a selenide will give an elimination reaction after oxidation, to leave behind an alkene and a SeO-selenoperoxol. The SeO-selenoperoxol is highly reactive and is not isolated as such. In the elimination reaction, all five participating reaction centers are coplanar and, therefore, the reaction stereochemistry is syn. Oxidizing agents used are hydrogen peroxide, ozone or MCPBA. This reaction type is often used with ketones leading to enones. An example is acetylcyclohexanone elimination with benzeneselenylchloride and sodium hydride.[26]

The Grieco elimination is a similar selenoxide elimination using o-nitrophenylselenocyanate and tributylphosphine to cause the elimination of the elements of H2O.

References

[edit]- ^ A. Krief, L. Hevesi, Organoselenium Chemistry I. Functional Group Transformations., Springer, Berlin, 1988 ISBN 3-540-18629-8

- ^ S. Patai, Z. Rappoport (Eds.), The Chemistry of Organic Selenium and Tellurium Compounds, John. Wiley and Sons, Chichester, Vol. 1, 1986 ISBN 0-471-90425-2

- ^ Paulmier, C. Selenium Reagents and Intermediates in Organic Synthesis; Baldwin, J. E., Ed.; Pergamon Books Ltd.: New York, 1986 ISBN 0-08-032484-3

- ^ Wallschläger, D.; Feldmann, F. (2010). Formation, Occurrence, Significance, and Analysis of Organoselenium and Organotellurium Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 7, Organometallics in Environment and Toxicology. RSC Publishing. pp. 319–364. ISBN 978-1-84755-177-1.

- ^ Löwig, C. J. (1836). "Ueber schwefelwasserstoff—und selenwasserstoffäther" [About hydrogen sulfide and selenium hydrogen ether]. Annalen der Physik. 37 (3): 550–553. Bibcode:1836AnP...113..550L. doi:10.1002/andp.18361130315.

- ^ a b Mukherjee, Anna J.; Zade, Sanjio S.; Singh, Harkesh B.; Sunoj, Raghavan B. (2010). "Organoselenium Chemistry: Role of Intramolecular Interactions". Chemical Reviews. 110 (7): 4357–4416. doi:10.1021/cr900352j. PMID 20384363.

- ^ Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 3, p. 771 (1955); Vol. 24, p. 89 (1944) Online Article.

- ^ Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 6, p. 533 (1988); Vol. 59, p. 141 (1979) Article

- ^ Chemistry of hypervalent compounds (1999) Kin-ya Akiba ISBN 978-0-471-24019-8

- ^ Link Developments in the chemistry of selenaheterocyclic compounds of practical importance in synthesis and medicinal biology Arkivoc 2006 (JE-1901MR) Jacek Młochowski, Krystian Kloc, Rafał Lisiak, Piotr Potaczek, and Halina Wójtowicz

- ^ Okazaki, R.; Tokitoh, N. (2000). "Heavy ketones, the heavier element congeners of a ketone". Accounts of Chemical Research. 33 (9): 625–630. doi:10.1021/ar980073b. PMID 10995200.

- ^ Amouri, H.; Moussa, J.; Renfrew, A. K.; Dyson, P. J.; Rager, M. N.; Chamoreau, L.-M. (2010). "Discovery, Structure, and Anticancer Activity of an Iridium Complex of Diselenobenzoquinone". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 49 (41): 7530–7533. doi:10.1002/anie.201002532. PMID 20602399.

- ^ Block, E. (2010). Garlic and Other Alliums: The Lore and the Science. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-0-85404-190-9.

- ^ Axley, M.J.; Böck, A.; Stadtman, T.C. (1991). "Catalytic properties of an Escherichia coli formate dehydrogenase mutant in which sulfur replaces selenium". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 (19): 8450–8454. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88.8450A. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.19.8450. PMC 52526. PMID 1924303.

- ^ Papp, L.V.; Lu, J.; Holmgren, A.; Khanna, K.K. (2007). "From selenium to selenoproteins: synthesis, identity, and their role in human health". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 9 (7): 775–806. doi:10.1089/ars.2007.1528. PMID 17508906.

- ^ Comasseto, João Valdir; Ling, Lo Wai; Petragnani, Nicola; Stefani, Helio Alexandre (1997). "Vinylic Selenides and Tellurides - Preparation, Reactivity and Synthetic Applications". Synthesis. 1997 (4): 373. doi:10.1055/s-1997-1210. S2CID 260336441.

- ^ Comasseto, J (1983). "Vinylic selenides". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 253 (2): 131–181. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(83)80118-1.

- ^ Zeni, Gilson; Stracke, Marcelo P.; Nogueira, Cristina W.; Braga, Antonio L.; Menezes, Paulo H.; Stefani, Helio A. (2004). "Hydroselenation of Alkynes by Lithium Butylselenolate: an Approach in the Synthesis of Vinylic Selenides". Organic Letters. 6 (7): 1135–8. doi:10.1021/ol0498904. PMID 15040741.

- ^ Dabdoub, M (2001). "Synthesis of (Z)-1-phenylseleno-1,4-diorganyl-1-buten-3-ynes: hydroselenation of symmetrical and unsymmetrical 1,4-diorganyl-1,3-butadiynes". Tetrahedron. 57 (20): 4271–4276. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00337-4.

- ^ Doregobarros, O; Lang, E; Deoliveira, C; Peppe, C; Zeni, G (2002). "Indium(I) iodide-mediated chemio-, regio-, and stereoselective hydroselenation of 2-alkyn-1-ol derivatives". Tetrahedron Letters. 43 (44): 7921. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)01904-4.

- ^ Comasseto, J (1981). "Stereoselective synthesis of vinylic selenides". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 216 (3): 287–294. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)85812-X.

- ^ Organic Syntheses Coll. Vol. 9, p. 396 (1998); Vol. 71, p. 181 (1993) Online article Archived 2005-10-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Organic Syntheses Coll. Vol. 6, p. 946 (1988); Vol. 56, p. 25 (1977). Online article Archived 2005-11-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 4, p. 229 (1963); Vol. 32, p. 35 (1952). Online article Archived 2005-11-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Riley, Harry Lister; Morley, John Frederick; Friend, Norman Alfred Child (1932). "255. Selenium dioxide, a new oxidising agent. Part I. Its reaction with aldehydes and ketones". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 1875. doi:10.1039/JR9320001875.

- ^ Organic Syntheses Coll. Vol. 6, p. 23 (1988); Vol. 59, p. 58 (1979) Online Article