Soham

| Soham | |

|---|---|

Soham town sign | |

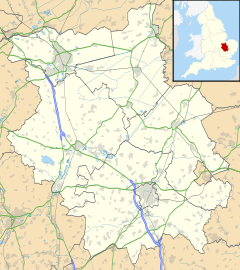

Location within Cambridgeshire | |

| Area | 8.2 sq mi (21 km2) [1] |

| Population | 12,336 [2] |

| • Density | 1,504/sq mi (581/km2) |

| OS grid reference | L591732 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ELY |

| Postcode district | CB7 |

| Dialling code | 01353 |

| Police | Cambridgeshire |

| Fire | Cambridgeshire |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| UK Parliament | |

Soham (/ˈsoʊəm/ SOH-əm) is a town and civil parish in the district of East Cambridgeshire, in Cambridgeshire, England, just off the A142 between Ely and Newmarket. Its population was 12,336 at the 2021 census.[2]

History

[edit]Archaeology

[edit]The region between Devil's Dyke and the line between Littleport and Shippea Hill shows a remarkable amount of archaeological findings of the Stone Age, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. A couple of hoards of bronze objects are found in the area of Soham, including one with swords and spearheads of the later Bronze Age as well as a gold torc, retrieved in 1938.[3]

A large Anglo-Saxon settlement was discovered on land between Brook Street and Fordham Road, next to Roman remains in the old Fisky's Hill area and former allotment site in 2013 and onwards. During the establishment of the Fordham Road cemetery, in the late 1800s, burial remains were also found with several high-status grave goods, including a girdle hanger, beads and jewellery. These items are now housed in the British Museum. Further Bronze and Iron Age settlements and related activity has also been noted in the north of the town during recent development on the sites. Many Neolithic items have been found whilst field walking to the East of the town along with fossils towards the bypass.

An extensive ditch system, not visible via aerial photography, has also been identified, as well as a wooden trackway 800 m (870 yd) in length between Fordey Farm (Barway) and Little Thetford, with associated shards of later Bronze Age pottery (1935).[4]

Name and early geography

[edit]According to an article published in Fenland Notes & Queries in 1899:[5]

In the Domesday Survey the name of the parish is spelt 'Soeham,' or 'Seaham', and in more modern works 'Seham'. Other forms met with are Soame, Shoame, Swoham, Some, Saham. Soham is spelt 'Soegham' in Charter No. 865. It occurs in a will of Ælfloed about AD 972; this will recites the will of Queen Æthelfloed, wife of King Edmund I. It concerns grants of land at Rettendon, Soham, and Ditton. The Anglo-Saxon name is 'Soegham'. 'Soeg' is obviously the same as Swedish dialect 'sogg', wet, 'swampy', related to 'sagt', drenched; all from the root verb seen in Anglo-Saxon 'sigan', to sink, drain; whence also the Icelandic 'saggi', moisture, dampness...

The names Eye Hill, Eau Fen, Soham Mere all point to the time when what is now cultivated land, was nothing more than a watery waste. Qua Fen may be a corruption of 'Quay', ie, the place where ships used to load and unload [suggesting that] Soham was, before the drainage of the Fens, a seaport town, its chief trade being with King's Lynn. Quay Fen is sometimes found as 'Calf Fen'. Soham Mere is spoken of (1794) as the largest lake in England, next in order of size being Ramsay and Whittlesey Meres. Mere is the Anglo-Saxon for lake or marsh.

Soham Mere finds mention in Liber Eliensis[7] relating King Cnut's winter visit to the monks of Ely for the Feast of the Purification. This tale was elaborated as an 'Old English Novelet' in 1844,[8] describing how King Cnut's nobles were concerned for his safety in crossing the Soham Mere ice. If the ice broke this would drown the king in the Fen waters. Cnut insisted on travelling (in a sledge[9]) should there be a fenner to lead him across. One Brethner – an Ely fenner, named Budde or Pudding on account of his large size – elected to lead the king. Cnut replied if the ice could hold Brethner's weight it would surely hold his. Thus the king and his retinue followed over the "bending and cracking ice" to Ely. Brethner, a serf, was set free by the king with some free lands for his good deed.

But by 1813 the lake was no more: an agricultural study describes the area:[5][10]

On the east of the town, a black sandy moor, lying upon a gravel; the remainder a deep, rich black mould, lying upon a blue clay or gault or clunch. Pasture extensive of first quality; a large tract also of second quality. The Mere, formerly a lake, now drained and cultivated – and the soil a mixture of vegetable matter and brown clay, contains about fourteen hundred acres.

St Felix

[edit]St Felix of Burgundy, 'Apostle of the East Angles', founded Soham Abbey in Soham around 630 AD but it was destroyed by the Danes in 870 AD. Luttingus, an Anglo-Saxon nobleman, built a cathedral and palace at Soham around 900 AD,[11] on the site of the present-day Church of St Andrew and adjacent land.

St Andrew's Church dates from the 12th century. Traces of the Saxon cathedral are said to still exist within the church. In 1102 Hubert de Burgh, Chief Justice of England, granted 'Ranulph' certain lands in trust for the Church of St Andrew. Ranulph is recorded as the first Vicar of Soham and had a hand in designing the 'new' Norman church. The current church is mainly later, the tower being the latest addition in the 15th century. This tower was built to replace a fallen crossing tower and now contains ten bells. The back six were cast in 1788, with two new trebles and two bells being recast in 1808. There are some pictures and a description of the church at the Cambridgeshire Churches website.[12]

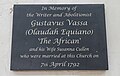

Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa 'The African'

[edit]The first black British author and anti-slave activist, Olaudah Equiano, also known as Gustavus Vassa, married a local girl, Susannah Cullen, at St Andrew's Church, on 7 April 1792 and the couple lived in the town for several years.

They had two daughters. Anna Maria was born on 16 October 1793 and baptised in St Andrew's on 30 January 1794. Their second child, Joanna Vassa, was born on 11 April 1795 and was baptised in the parish church on 29 April 1795.

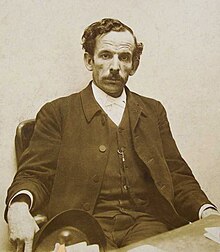

William Case Morris

[edit]

William Case Morris (1864–1932) was born in Soham on 16 February 1864. He and his father left the town in search of a new life in 1872 after the death of his mother in 1868, finally settling in Argentina in 1874. Morris was horrified by the poverty of the street children, which led him to found several children's homes in Buenos Aires. Morris returned to Soham shortly before his death on 15 September 1932, and was buried in the Fordham Road cemetery. He is commemorated with a statue in Palermo, Buenos Aires as well as railway stations, football stadia and a town, William C. Morris, Buenos Aires, named after him. His legacy lives on with the Biblioteca Popular William C. Morris and 'Hogar el Alba' children's homes located in Buenos Aires which help impoverished children.[13]

Soham rail disaster

[edit]

The town narrowly escaped destruction on 2 June 1944, during the Second World War, when a fire developed on the leading wagon of a heavy ammunition train travelling slowly through the town. The town was saved by the bravery of four railway staff, Benjamin Gimbert (driver), James Nightall (fireman), Frank Bridges (signalman) and Herbert Clarke (guard), who uncoupled the rest of the train and drove the engine and lead wagon clear of the town, where it exploded, killing Jim Nightall and Frank Bridges but causing no further deaths. Ben Gimbert survived and spent seven weeks in hospital. Although small in comparison to what would have happened if the entire train had blown up, the explosion caused substantial property damage. Gimbert and Nightall were both awarded the George Cross (Nightall posthumously). A permanent memorial was unveiled on 2 June 2007 by Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester followed by a service in St Andrew's Church. The memorial is constructed of Portland stone with a bronze inlay depicting interpretive artwork of the damaged train and text detailing the incident.

Soham murders

[edit]

In August 2002, Soham became the centre of national media attention following the disappearance and murder of two 10-year-old girls, Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman, who both lived in Soham. They disappeared from the family home of Holly Wells in Redhouse Gardens on the evening of 4 August. Both were found dead some 10 miles (16 km) away, near RAF Lakenheath, on 17 August.[14]

In December 2003, Ian Huntley, who had been employed as the caretaker at the local secondary school, Soham Village College, was convicted of their murders and sentenced to life in prison. He had given a number of police and television interviews while the girls were missing, claiming to have seen them on the evening of their disappearance, and was finally arrested several hours before their bodies were found, following the recovery of clothing belonging to the girls on the school site.[15]

The caretaker's house in College Close where Huntley lived and, as admitted at his trial, where the girls died, was demolished in 2004.[16]

Schools in Soham

[edit]- Soham Village College

- St Andrew's Primary School[17]

- The Weatheralls Primary School[18]

- The Shade Primary School[19]

- Little Wombatz (Pre-School)

Transport

[edit]The A142 road from Ely to Newmarket runs past Soham, and formerly ran through the town.[20] Soham is served by an hourly bus service Monday to Friday (the number 112, on a route linking Newmarket and Ely) with a reduced service on Saturday. Following Stagecoach's cancellation of route 12 on 30 October 2022,[21] Stephenson of Essex took on the route, renumbering it as route 112[22] to avoid clashing with its existing Newmarket to Cambridge route 12.

Soham railway station closed to passengers in 1965, and reopened in December 2021.[23] The line through Soham remained open for passenger and goods services between the Midlands and Ipswich, Harwich and Felixstowe. After local campaigns for its reopening, it was announced in June 2020 that a new station would be built on the old site.[24] Initial works on the station started in autumn 2020, followed by the main construction during 2021. The first timetabled passenger train to stop at Soham Station for 56 years was the 06:49 towards Ely and Peterborough on Monday 13 December 2021.

Media

[edit]Local news and television programmes are provided by BBC East and ITV Anglia. Television signals are received from either the Sandy Heath or Tacolneston TV transmitters.[25][26] Local radio stations are BBC Radio Cambridgeshire, Heart East, and Star Radio. The town's local newspapers are the Ely Standard and Cambridge News.[27]

Sport and leisure

[edit]The Ross Peers Sports Centre is run by the Soham & District Sports Association Committee and is home to the Soham Indoor Bowls Club and Rink Hockey Team

Soham have two non-league football clubs, Soham Town Rangers F.C., who play at Julius Martin Lane, and Soham United FC.

See also

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

St Andrew's Church, Soham

-

William Case Morris Stained Glass Window in St. Andrew's Church

-

Commemorative Plaque of the 7 April, 1792, marriage of Gustavus Vassa and Susannah Cullen in St Andrew's Church, Soham

-

Soham War Memorial

-

Northfields Windmill

-

Downfields Windmill

-

The Red Lion

-

The Fountain & Steelyard Weighing Machine

-

The Ship

-

The Carpenter's Arms

-

The Cherry Tree

-

East Fen Common

-

Qua Fen Common

-

Angle Common

-

South Horse Fen

-

Soham Carnival & Heavy Horse Show

-

Soham Pumpkin Fair

References

[edit]- ^ Research Group (2010). "Historic Census Population Figures". Cambridgeshire County Council. Archived from the original (XLS) on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Key Figures for 2021 Census: Key Statistics. Area: Soham (Parish)". ONS. 2021.

- ^ Hall, David (1994). Fenland survey: an essay in landscape and persistence / David Hall and John Coles. London; English Heritage. ISBN 1-85074-477-7., p. 81-88

- ^ Lethbridge, T.C. (1934). "Investigations of the Ancient Causeway in the Fen between Fordy and Little Thetford". Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society. XXXV: 86–89.

- ^ a b Olorenshaw, J. W. (1891). Saunders, W. H. Bernard (ed.). "125. History of Soham". Fenland Notes & Queries. 1. Peterborough, Cambs.: Geo. C. Caster: 163–164.

- ^ Cantabrigensis Comitatvs – Atlas Maior, vol 5, map 24 – Joan Blaeu, 1667 – BL 114.h(star).5.(24)

- ^ Liber Eliensis. 1100s. pp. Lib 2, p203.

- ^ MacFarlane, Charles (1844). "The Happy End". The Camp of Refuge. London, Ludgate Street: Charles Knight. pp. 227–8.

- ^ MacFarlane, Charles (1887). Miller, Samuel Henry (ed.). The Camp of Refuge (2nd Annotated ed.). Cambs, Wisbech: Leach & Son. p. 466.

- ^ Gooch, W. (1813). "On Soils". A general view of the Agriculture of the County of Cambridge.

- ^ "Our History". www.standrews-soham.org.uk. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ This church's page at the Cambridgeshire Churches website

- ^ Hogarelalba.com.ar[permanent dead link], accessed 18 September 2009

- ^ "Judge Gives Huntley Forty Years – And Little Hope". The Daily Telegraph. 30 September 2005. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ "Police Reveal Horrors of Bodies in Ditch". The Scotsman. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ "Soham Murder House is Demolished". BBC News. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ St-andrews-pri.cambs.sch.uk

- ^ Weatheralls.cambs.sch.uk

- ^ Theshadeprimary.org.uk

- ^ see old map

- ^ Atta, Fareid (21 September 2022). "Bus timetables: List of Cambridgeshire villages and bus routes affected by Stagecoach cuts". CambridgeshireLive. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ Spencer, Alex (25 October 2022). "New bus timetables released for cancelled Cambridgeshire routes". Cambridge Independent. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ Village history Archived 11 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Soham Museum

- ^ "Green light for Soham station". Network Rail Media Centre. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "Full Freeview on the Sandy Heath (Central Bedfordshire, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ "Full Freeview on the Tacolneston (Norfolk, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ "Ely Standard". British Papers. 18 June 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2023.