Aftermath of the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Brexit |

|---|

|

|

Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union Glossary of terms |

After the British EU membership referendum held on 23 June 2016, in which a majority voted to leave the European Union, the United Kingdom experienced political and economic upsets, with spillover effects across the rest of the European Union and the wider world. Prime Minister David Cameron, who had campaigned for Remain, announced his resignation on 24 June, triggering a Conservative leadership election, won by Home Secretary Theresa May. Following Leader of the Opposition Jeremy Corbyn's loss of a motion of no confidence among the Parliamentary Labour Party, he also faced a leadership challenge, which he won. Nigel Farage stepped down from leadership of the pro-Leave party UKIP in July. After the elected party leader resigned, Farage then became the party's interim leader on 5 October until Paul Nuttall was elected leader on 28 November.

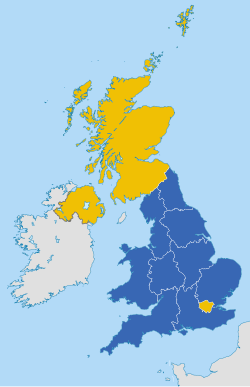

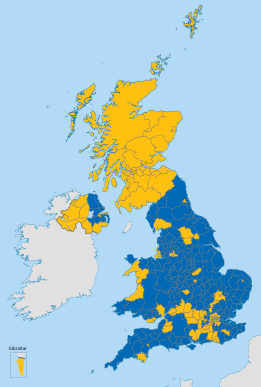

Voting patterns in the referendum varied between areas: Gibraltar, Greater London, many other cities, Scotland and Northern Ireland had majorities for Remain; the remainder of England and Wales and most unionist parts of Northern Ireland showed Leave majorities.[1] This fuelled concern among Scottish and Irish nationalists: the First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, threatened to withhold legislative consent for any withdrawal legislation and had formally requested permission to hold a Second Scottish Independence referendum, while the Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland called for a referendum on a United Ireland. The Status of Gibraltar and that of London were also questioned.

In late July 2016, the Foreign Affairs Select Committee was told that Cameron had refused to allow the Civil Service to make plans for Brexit, a decision the committee described as "an act of gross negligence".[2]

Economic effects

[edit]Economic arguments were a major element of the referendum debate. Remain campaigners and HM Treasury argued that trade would be worse off outside the EU.[3][4] Supporters of withdrawal argued that the cessation of net contributions to the EU would allow for some cuts to taxes or increases in government spending.[5]

On the day after the referendum, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney held a press conference to reassure the markets,[6] and two weeks later released £150 billion in lending.[7] Nonetheless, share prices of the five largest British banks fell an average of 21% on the morning after the referendum.[8] All of the Big Three credit rating agencies reacted negatively to the vote in June 2016: Standard & Poor's cut the British credit rating from AAA to AA, Fitch Group cut from AA+ to AA, and Moody's cut the UK's outlook to "negative".[9]

When the London Stock Exchange opened on Friday 24 June, the FTSE 100 fell from 6338.10 to 5806.13 in the first ten minutes of trading. Near the close of trading on 27 June, the domestically-focused FTSE 250 Index was down approximately 14% compared to the day before the referendum results were published.[10] However, by 1 July the FTSE 100 had risen above pre-referendum levels, to a ten-month high representing the index's largest single-week rise since 2011.[11] On 11 July, it officially entered bull market territory, having risen by more than 20% from its February low.[12] The FTSE 250 moved above its pre-referendum level on 27 July.[13] In the US, the S&P 500, a broader market than the Dow Jones, reached an all-time high on 11 July.[14]

On the morning of 24 June, the pound sterling fell to its lowest level against the US dollar since 1985.[15] The drop over the day was 8% – the biggest one-day fall in the pound since the introduction of floating exchange rates following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971.[16] The pound remained low, and on 8 July became the worst performing major currency of the year,[17] although the pound's trade-weighted index was only back at levels seen in the period 2008–2013.[18][19] It was expected that the weaker pound would also benefit aerospace and defence firms, pharmaceutical companies, and professional services companies; the share prices of these companies were boosted after the EU referendum.[20]

After the referendum, the Institute for Fiscal Studies published a report funded by the Economic and Social Research Council which warned that Britain would lose up to £70 billion in reduced economic growth if it did not retain Single market membership, with new trade deals unable to make up the difference.[21] One of these areas is financial services, which are helped by EU-wide "passporting" for financial products, which the Financial Times estimated indirectly accounted for up to 71,000 jobs and 10 billion pounds of tax annually[22] and there were concerns that banks might relocate outside the UK.[23]

On 5 January 2017, Andy Haldane, the Chief Economist and the Executive Director of Monetary Analysis and Statistics at the Bank of England, admitted that forecasts predicting an economic downturn due to the referendum were inaccurate and noted strong market performance after the referendum,[24][25][26] although some have pointed to prices rising faster than wages.[27]

Economy and business

[edit]On 27 June, Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne attempted to reassure financial markets that the British economy was not in serious trouble. This came after media reports that a survey by the Institute of Directors suggested that two-thirds of businesses believed that the outcome of the referendum would produce negative results as well as falls in the value of sterling and the FTSE 100. Some British businesses had also predicted that investment cuts, hiring freezes and redundancies would be necessary to cope with the results of the referendum.[28] Osborne indicated that Britain was facing the future "from a position of strength" and there was no current need for an emergency Budget.[29] "No-one should doubt our resolve to maintain the fiscal stability we have delivered for this country ... And to companies, large and small, I would say this: the British economy is fundamentally strong, highly competitive and we are open for business."[30]

On 14 July Philip Hammond, Osborne's successor as Chancellor, told BBC News the referendum result had caused uncertainty for businesses, and that it was important to send "signals of reassurance" to encourage investment and spending. He also confirmed there would not be an emergency budget: "We will want to work closely with the governor of the Bank of England and others through the summer to prepare for the Autumn Statement, when we will signal and set out the plans for the economy going forward in what are very different circumstances that we now face, and then those plans will be implemented in the Budget in the spring in the usual way."[31]

On 12 July, the global investment management company BlackRock predicted the UK would experience a recession in late 2016 or early 2017 as a result of the vote to leave the EU, and that economic growth would slow down for at least five years because of a reduction in investment.[32] On 18 July, the UK-based economic forecasting group EY ITEM club suggested the country would experience a "short shallow recession" as the economy suffered "severe confidence effects on spending and business"; it also cut its economic growth forecasts for the UK from 2.6% to 0.4% in 2017, and 2.4% to 1.4% for 2018. The group's chief economic adviser, Peter Soencer, also argued there would be more long-term implications, and that the UK "may have to adjust to a permanent reduction in the size of the economy, compared to the trend that seemed possible prior to the vote".[33] Senior City investor Richard Buxton also argued there would be a "mild recession".[34] On 19 July, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reduced its 2017 economic growth forecast for the UK from 2.2% to 1.3%, but still expected Britain to be the second fastest growing economy in the G7 during 2016; the IMF also reduced its forecasts for world economic growth by 0.1% to 3.1% in 2016 and 3.4% in 2017, as a result of the referendum, which it said had "thrown a spanner in the works" of global recovery.[35]

On 20 July, a report released by the Bank of England said that although uncertainty had risen "markedly" since the referendum, it was yet to see evidence of a sharp economic decline as a consequence. However, around a third of contacts surveyed for the report expected there to be "some negative impact" over the following year.[36]

In September 2016, following three months of positive economic data after the referendum, commentators suggested that many of the negative statements and predictions promoted from within the "remain" camp had failed to materialise,[37] but by December, analysis began to show that Brexit was having an effect on inflation.[38]

In April 2017 the IMF raised their forecast for the British economy from 1.5% to 2% for 2017 and from 1.4% to 1.5% for 2018.[39]

Party politics

[edit]Conservative

[edit]

On 24 June, the Conservative Party leader and prime minister, David Cameron, announced that he would resign by October because the Leave campaign had been successful in the referendum.[40] Although most of the Conservative MPs on both sides of the referendum debate had urged him to stay, the UKIP leader, Nigel Farage, called for Cameron to go "immediately".[41] A leadership election was scheduled for 9 September, with the new leader to be in place before the party's autumn conference on 2 October.[42] The two main candidates were predicted to be Boris Johnson, who had been a keen supporter of leaving the EU, and Home Secretary Theresa May, who had campaigned for Remain.[43] The last-minute candidature by Johnson's former ally Michael Gove destabilised the race and forced Johnson to stand down; the final two candidates became May and Andrea Leadsom.[44][45] Leadsom soon withdrew, leaving May as new party leader and next prime minister.[46] She took office on 13 July.[47]

Labour

[edit]The Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn faced growing criticism from his parliamentary party MPs, who had supported remaining within the EU, for poor campaigning,[48] and two Labour MPs submitted a vote of no confidence in Corbyn on 24 June.[49] It is claimed that there is evidence that Corbyn deliberately sabotaged Labour's campaign to remain part of the EU, despite remain polling favourably among Labour voters.[50] In the early hours of Sunday 26 June, Corbyn sacked Hilary Benn (the shadow foreign secretary) for apparently leading a coup against him. This led to a string of Labour MPs quickly resigning their roles in the party.[51] By mid-afternoon on 27 June 2016, 23 of the Labour Party's 31 shadow cabinet members had resigned from the shadow cabinet as had seven parliamentary private secretaries. On 27 June 2016, Corbyn filled some of the vacancies and was working to fill the others.[52]

According to a source quoted by the BBC, the party's Deputy Leader Tom Watson told leader Jeremy Corbyn that "it looks like we are moving towards a leadership election." Corbyn stated that he would run again in that event.[53] A no confidence motion was held on 28 June 2016; Corbyn lost the motion with more than 80% (172) of MPs voting against him with a turnout of 95%.[54]

Corbyn responded with a statement that the motion had no "constitutional legitimacy" and that he intended to continue as the elected leader. The vote does not require the party to call a leadership election[55] but, according to The Guardian: "the result is likely to lead to a direct challenge to Corbyn as some politicians scramble to collect enough nominations to trigger a formal challenge to his leadership."[56] By 29 June, Corbyn had been encouraged to resign by Labour Party stalwarts such as Dame Tessa Jowell, Ed Miliband and Dame Margaret Beckett.[57] Union leaders rallied behind Corbyn, issuing a joint statement saying that the Labour leader had a "resounding mandate" and a leadership election would be an "unnecessary distraction". Supporting Corbyn, John McDonnell said, "We're not going to be bullied by Labour MPs who refuse to accept democracy in our party."[58]

On 11 July, Angela Eagle announced her campaign for the Labour party leadership after attaining enough support of MPs to trigger a leadership contest, saying that she "can provide the leadership that Corbyn can't".[59] Eagle subsequently dropped out of the race (on 18 July) leaving Owen Smith as the only contender to Jeremy Corbyn.[60]

Smith had supported the campaign for Britain to remain in the European Union, in the referendum on Britain's membership in June 2016.[61] On 13 July 2016, following the vote to leave the EU, three weeks prior, he pledged that he would press for an early general election or offer a further referendum on the final 'Brexit' deal drawn up by the new prime minister, were he to be elected Labour leader.[62]

Approximately two weeks later, Smith told the BBC that (in his view) those who had voted with the Leave faction had done so "because they felt a sense of loss in their communities, decline, cuts that have hammered away at vital public services and they haven't felt that any politicians, certainly not the politicians they expect to stand up for them..." His recommendation was to "put in place concrete policies that will bring real improvements to people's lives so I'm talking about a British New Deal for every part of Britain..."[63]

Liberal Democrats

[edit]The Lib Dems, who are a strongly pro-European party, announced that they respect the referendum result, but would make remaining in the EU a manifesto pledge at the next election.[64] Leader Tim Farron said that "The British people deserve the chance not to be stuck with the appalling consequences of a leave campaign that stoked that anger with the lies of Farage, Johnson and Gove."[64]

More United

[edit]In reaction to the lack of a unified pro-EU voice following the referendum, members of the Liberal Democrats and others discussed the launch of a new centre-left political movement.[65] This was officially launched on 24 June as More United, named after a line in the maiden speech of Labour MP Jo Cox, who was killed during the referendum campaign.[66] More United is a cross-party coalition, and will crowdfund candidates from any party who support its goals, which include environmentalism, a market economy with strong public services, and close co-operation with the EU.[67]

UKIP

[edit]The UK Independence Party was founded to press for British withdrawal from the EU, and following the referendum its leader Nigel Farage announced, on 4 July, that having succeeded in this goal, he would stand down as leader.[68] Following the resignation of the elected leader Diane James, Farage became the interim party leader on 5 October.[69] Farage's successor Paul Nuttall was elected the party leader on 28 November 2016.[70]

General politics

[edit]The government and the civil service is heavily focused on Brexit. Former Head of the Home Civil Service Bob Kerslake has stated that there is a risk that other matters will get insufficient attention until they develop into crises.[71]

A cross party coalition of MP's has been formed to oppose hard Brexit. This group is known as, the all-party parliamentary group on EU relations. Chuka Umunna said that MP's should be active players rather than spectators, he said, “We will be fighting in parliament for a future relationship with the EU that protects our prosperity and rights at work, and which delivers a better and safer world.”[72]

Second general election

[edit]Under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, the next general election was scheduled to be held on 7 May 2020.[73]

Following the referendum, some political commentators argued that it might be necessary to hold an early general election before negotiations to leave began.[74] The final two candidates in the Conservative Party leadership election – Andrea Leadsom and Theresa May – said they would not seek an early general election.[75][76] However, after Leadsom's withdrawal and with May thus due to become prime minister without any broader vote, there were renewed calls for an early election from commentators[77] and politicians. Tim Farron, leader of the Liberal Democrats, called for an early election shortly after Leadsom's withdrawal.[78]

Despite repeatedly previously ruling out an early general election, May announced on 18 April 2017 her intention to call an election on 8 June 2017. This required a two-thirds super-majority of the Commons in support of a motion for an early general election, which was agreed on 19 April. May stated that "division in Westminster will risk ability to make a success of Brexit and it will cause damaging uncertainty and instability to the country... We need a general election and we need one now, because we have at this moment a one-off chance to get this done while the European Union agrees its negotiating position and before the detailed talks begin. I have only recently and reluctantly come to this conclusion."[79]

The snap election resulted in an unexpected hung parliament, with the Conservatives losing their overall majority but remaining as the largest party, which led to further political turmoil.

Pressure groups

[edit]Numerous pressure groups were established after the referendum to oppose Brexit.[80]

Former prime ministers' views

[edit]A week after the referendum, Gordon Brown, a former Labour prime minister who had signed the Lisbon Treaty in 2007, warned of a danger that in the next decade the country would be refighting the referendum. He wrote that remainers were feeling they must be pessimists to prove that Brexit is unmanageable without catastrophe, while leavers optimistically claim economic risks are exaggerated.[81]

The previous Labour prime minister, Tony Blair, in October 2016 called for a second referendum, a decision through parliament or a general election to decide finally if Britain should leave the EU.[82] Former leader of the Conservative prime minister John Major argued in November 2016 that parliament will have to ratify whatever deal is negotiated and then, depending on the deal there could be a case for a second referendum.[83]

Withdrawal negotiations

[edit]In the summer of 2018, a survey by YouGov indicated that five British people believed the government was handling negotiations badly for every one who approves of the government's negotiations. In another survey, voters indicated dissatisfaction not only with the British government. The polling organisation NatCen found 57% believed the EU was handling Brexit talks badly, while only 16% believe it was doing well.[84]

Immigration concerns

[edit]To what extent free movement of people would or would not be retained in any post-Brexit deal with the EU has emerged as a key political issue. Shortly after the result, the Conservative politician Daniel Hannan, who campaigned for Leave, told the BBC's Newsnight that Brexit was likely to change little about the freedom of movement between the UK and the European Union, concluding "We never said there was going to be some radical decline ... we want a measure of control."[85][86][87][88]

Theresa May stated in August 2016 that leaving the EU 'must mean controls on the numbers of people who come to Britain from Europe but also a positive outcome for those who wish to trade goods and services'.[89][90] According to a Home Office document leaked in September 2017, the UK planned to end the free movement of labour immediately after Brexit and introduce restrictions to deter all but highly skilled EU workers. It proposed offering low-skilled workers residency for a maximum of two years and the highly skilled work permits for three to five years.[91]

Boris Johnson initially argued that restricting freedom of movement was not one of the main reasons why people have voted Leave, but his position was seen as too lax on the issue by other Conservative Party Leave supporters, which may have contributed to Michael Gove's decision to stand in the party's leadership contest.[92] Meanwhile, EU leaders warned that full access to the single market would not be available without retaining free movement of people.[93] Limitations on the free movement of EU citizens within the UK will also have consequences for research and innovation. While campaigning in the Conservative leadership contest, Gove pledged to end the freedom of movement accord with the EU and instead implement an Australian-style points system.[citation needed]

Natasha Bouchard, the Mayor of Calais, suggests that the government of France should renegotiate the Le Touquet treaty, which allows British border guards to check trains, cars and lorries before they cross the Channel from France to Britain and therefore to keep irregular immigrants away from Britain.[94][95] French government officials doubt that the trilateral agreement (it includes Belgium) would be valid after the UK has officially left the European Union and especially think that it is unlikely that there will be any political motivation to enforce the agreement.[96] However, on 1 July 2016 François Hollande said British border controls would stay in place in France, though France had suggested during the referendum campaign that they would be scrapped, allowing migrants in the "Calais Jungle" camp easy access to Kent.[citation needed]

In late July 2016, discussions were underway that might provide the UK with an exemption from the EU rules on refugees' freedom of movement for up to seven years. Senior British government sources confirmed to The Observer that this was "certainly one of the ideas now on the table".[97] If the discussions led to an agreement, the UK – though not an EU member – would also retain access to the single market but would be required to pay a significant annual contribution to the EU. According to The Daily Telegraph the news of this possibility caused a rift in the Conservative Party: "Tory MPs have reacted with fury ... [accusing European leaders of] ... failing to accept the public's decision to sever ties with the 28-member bloc last month."[98]

According to CEP analysis of the Labour Force Survey, immigrants in the UK are on average more educated than UK-born citizens. Citizens in the UK are concerned that immigrants are taking over their jobs, for most immigrants are highly educated; however, they are actually helping the economy because they too consume goods, and produce jobs.[99] Immigrants to the UK help to mitigate the negative effects of the ageing British labour force and are believed to have an overall net positive fiscal effect. Some have argued that immigration has a dampening effect on wages due to the greater supply of labour.[100] However, other studies suggest that immigration has only a small impact on the average wage of workers. Immigration may have a negative impact on the wages of low-skilled workers but can push up the wages of medium- and highly paid workers.[101]

Status of current EU immigrants and British emigrants

[edit]There were about 3.7 million EU citizens (including Irish) living in the UK in 2016 and around 1.2 million British citizens living in other EU countries.[102] The future status of both groups of people and their reciprocal rights are the object of Brexit negotiations.[103] According to the British Office for National Statistics, 623,000 EU citizens came to live in England and Wales before 1981. A further 855,000 arrived before the year 2000. As of 2017, approximately 1.4 million Eastern Europeans were living in Britain, including 916,000 Poles.[104] In May 2004, when the EU welcomed ten new member states from a majority of Central and Eastern European countries, the UK was one of only three EU member states, alongside Sweden and Ireland, to open their labour market immediately to these new EU citizens.[102][105] In the 12 months following the referendum, the estimated number of EU nationals immigrating to the UK fell from 284,000 to 230,000. In parallel, the number of EU citizens emigrating from the UK increased from an estimated 95,000 in the year before the vote to 123,000. Annual net immigration from the EU to the UK has, thus, fallen to about 100,000.[102]

Theresa May, when candidate for Conservative leader, suggested that the status of EU immigrants currently in the UK could be used in negotiations with other European countries, with the possibility of expelling these people if the EU does not offer favourable exit terms.[106] This position has been strongly rejected by other politicians from both Remain and Leave campaigns.[103] In response to a question by Labour Leave campaigner Gisela Stuart, the Minister for Security and Immigration James Brokenshire said that the Government was unable to make any promises about the status of EU citizens in the UK before the government had set out negotiating positions, and that it would seek reciprocal protection for British citizens in EU countries.[107]

The Vice-Chancellor of Germany, Sigmar Gabriel, announced that the country would consider easing citizenship requirements for British nationals currently in Germany, to protect their status.[108] The foreign ministry of Ireland stated that the number of applications from British citizens for Irish passports increased significantly after the announcement of the result of the referendum on the membership in the European Union.[109][110] The Irish Embassy in London usually receives 200 passport applications a day, which increased to 4,000 a day after the vote to leave.[111] Other EU nations also had increases in requests for passports from British citizens, including France and Belgium.[111]

EU funding

[edit]Cornwall voted to leave the EU but Cornwall Council issued a plea for protection of its local economy and to continue receiving subsidies, as it had received millions of pounds in subsidies from the EU.[112]

After the referendum, leading scientists expressed fear of a shortfall in funding for research and science and worried that the UK had become less attractive for scientists.[113] The British science minister, Jo Johnson said the government would be on the watch for discrimination against British scientists, after stories circulated about scientists being left out of joint grant proposals with other EU scientists in the aftermath of the referendum.[114] On 15 August 2016, ministers announced that research funding would be matched by the British government.[115]

In October 2016, government ministers announced that the UK would be investing 220 million pounds ($285 million) in support of the nation's technology industry.[116] The consequences of Brexit for academia will become clearer once negotiations for Britain's post-Brexit relationship with the EU get under way.

The European Union Youth Orchestra announced in October 2017 that, as a result of Brexit, it intends to relocate from London to Italy. It is expected British youth will cease being eligible to participate in the orchestra in future.[117]

British participation in European institutions

[edit]As of January 2018, the European Commission had announced that three European agencies would be leaving the UK as a consequence of its withdrawal from the EU: the European Medicines Agency, European Banking Authority and the Galileo Satellite Monitoring Agency.

Republic of Ireland–United Kingdom border

[edit]The United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland are members of the Common Travel Area, which allows free movement between these countries. If the UK negotiates a settlement with the EU that does not involve freedom of movement, while the Republic of Ireland remains an EU member, an open border between the Republic and Northern Ireland is likely to become untenable.[118] Martin McGuinness, deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, said this would "seriously undermine" the Good Friday Agreement that brought an end to the Troubles.[119] David Cameron pledged to do whatever possible to maintain the open border.[120] Since becoming prime minister Theresa May has reassured both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland that there will not be a "hard (customs or immigration) border" on the island of Ireland.[121]

Notification of intention to leave the EU (Article 50)

[edit]The most likely way that exit from the EU is activated is through Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. The British government chooses when to invoke, although theoretically the other members of the European Union could refuse to negotiate before invocation.[122] This will be the first time that this article has been invoked. The government can theoretically ignore the result of the referendum.[123]

Although Cameron had previously announced that he would invoke Article 50 on the morning after a Leave vote, he declared during his resignation that the next prime minister should activate Article 50 and begin negotiations with the EU.[124] During the Conservative leadership contest, Theresa May expressed that the UK needs a clear negotiating position before triggering Article 50, and that she would not do so in 2016.[125] The other 27 members of the EU issued a joint statement on 26 June 2016 regretting but respecting the UK's decision and asking it to proceed quickly in accordance with Article 50.[126] This was echoed by the EU Economic Affairs Commissioner Pierre Moscovici.[127] However, with the next French presidential election being held in April and May 2017, and the next German federal election likely to be held in autumn 2017, "people close to the E.U. Commission" were reported as saying that the European Commission was at the time working under the assumption that Article 50 notification would not be made before September 2017.[128]

On 27 June 2016, a "Brexit unit" of civil servants were tasked with "intensive work on the issues that will need to be worked through in order to present options and advice to a new Prime Minister and a new Cabinet",[129] while on 14 July, David Davis was appointed to the newly created post of Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, or "Brexit Secretary", with a remit to oversee the UK's negotiations for withdrawing from the EU.[130] Davis called for a "brisk but measured" approach to negotiations, and suggested the UK should be ready to trigger Article 50 "before or by the start of" 2017, saying "the first order of business" should be to negotiate trade deals with countries outside the European Union. However, Oliver Letwin, a former Minister of State for Europe, warned that the UK had no trade negotiators to lead such talks.[131]

Having previously ruled out starting the Article 50 process before 2017,[131] on 15 July 2016, following a meeting with Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, May said that it would not begin without a coherent "UK approach" to negotiations.[132] Lawyers representing the government in a legal challenge over the Article 50 process said that May would not trigger Article 50 before 2017.[133] However, in September 2016, The Washington Post highlighted the lack of coherent strategy following what it described as the "hurricane-strength political wreckage" left by the Brexit vote. It said the public still had no idea what the oft-repeated "Brexit means Brexit" meant and there have been nearly as many statements on what the objectives were as there are cabinet ministers.[134]

The Supreme Court ruled in the Miller case in January 2017 that the government needed parliamentary approval to trigger Article 50.[135][136] After the House of Commons overwhelmingly voted, on 1 February 2017, for the government's bill authorising the prime minister to invoke Article 50,[137] the bill passed into law as the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017. Theresa May signed the letter invoking Article 50 on 28 March 2017, which was delivered on 29 March by Tim Barrow, the British ambassador to the EU, to Donald Tusk.[138][139][140]

Informal discussions

[edit]On 20 July 2016, following her first overseas trip as prime minister, during which she flew to Berlin for talks with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Theresa May reaffirmed her intention not to trigger Article 50 before 2017, suggesting it would take time for the UK to negotiate a "sensible and orderly departure" from the EU. However, although Merkel said it was right for the UK to "take a moment" before beginning the process, she urged May to provide more clarity on a timetable for negotiations. Shortly before travelling to Berlin, May had also announced that in the wake of the referendum, Britain would relinquish the presidency of the Council of the European Union, which passes between member states every six months on a rotation basis, and that the UK had been scheduled to hold in the second half of 2017.[141][142]

Geographical variations within the UK, and implications

[edit]The distribution of Remain and Leave votes varied dramatically across the country.[1] Remain won every Scottish district, most London boroughs, Gibraltar and the predominantly Catholic parts of Northern Ireland, as well as many English and Welsh cities. Leave by contrast won almost all other English and Welsh districts and most of the predominantly Ulster Protestant districts, and won a majority in Wales as a whole as well as in every English region outside London. These results were interpreted by many commentators as revealing a "split" or "divided" country, and exacerbated regional tensions.[1][143]

Following the referendum result the all-party Constitution Reform Group proposed a federal constitutional structure for the United Kingdom. Among the proposals were the establishment of an English Parliament, replacing the House of Lords with a directly elected chamber, and greater devolution for the English regions, following a similar format to that of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority.[144][145] The group's Act of Union Bill was introduced in the House of Lords in October 2018, but its progress was terminated by the ending of the Parliamentary session in October 2019.[146]

England

[edit]

Of the four constituent countries in the United Kingdom, England voted most in favour of leaving the European Union with 53% of voters choosing to leave compared to 47% who chose to remain. Unlike Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, there was no centralised national count of the votes; instead England was split into the nine regions using the same boundaries as European Parliament elections. Eight of the nine English regions returned majority votes in favour of "Leave". The most decisive of these was in the West Midlands where 59% of voters chose to leave the EU, and every voting area except Warwick had majorities for "Leave". This included Birmingham – the UK area with the greatest number of eligible voters – which narrowly voted to leave by 3,800 votes.

The East Midlands was the second most enthusiastic region in favour of leaving the EU, voting to "Leave" by 58.8% of voters. The region saw all but two of the voting areas voting to leave with only mainly rural area of Rushcliffe and the city of Leicester choosing to "Remain" with the major cities of Nottingham, Northampton, Derby and Lincoln all being in favour of "Leave". The region also recorded the two local authority areas in the United Kingdom with the highest proportion in favour of leaving the EU: 75.6% in the Borough of Boston, and 73% in the neighbouring rural district council area of South Holland in Lincolnshire.[147]

The industrialised North East of England was the third most enthusiastic region in favour of leaving the EU. Newcastle upon Tyne only voted overall in favour of "Remain" by a majority of 1,987 votes whilst Sunderland supported leaving by a bigger margin with 61.4% of its voters. Redcar and Cleveland voted most heavily in favour of leaving, at 66.2%.

The Yorkshire & Humber region voted to leave the EU by almost 58% of its voters. All of its voting areas except for Harrogate, York and Leeds returned votes in favour of "Leave", with Doncaster being the most enthusiastic at 59%.

The East of England voted to leave the EU by 56.4% of its voters, although unlike the Midlands its voting was split on geographical lines. Rural and coastal areas in the region voted heavily to leave whilst the inland affluent university areas voted to remain. The city of Peterborough voted by 60% in favour of "Leave", whilst the university city of Cambridge voted in favour of "Remain" by 73% to 28%. Watford produced the narrowest result in favour of leaving the European Union in the United Kingdom, with a majority of 252 votes.

The South West of England and North West England also voted to leave the EU. In the South West region, the coastal fishing areas of Devon and Cornwall heavily supported leaving the EU with Sedgemoor showing the most support for leaving with 61.2% of voters choosing to leave. Bristol showed the most support for "Remain" at 61.7%. In the North West, the major metropolitan areas of Manchester, Trafford, Stockport and Liverpool and the affluent parts of the Lake District heavily voted to "Remain" whilst the less affluent and coastal areas all voted to "Leave".

South East England was the least enthusiastic of the English regions to vote in favour of leaving the EU: the electorate voted to leave by an overall majority of 176,185, which almost exactly mirrored the national outcome. Of the 67 voting areas, 43 returned majority votes in favour of "Leave", with Gravesham the most in favour, with 65% of voters choosing to leave. The channel ports of Dover, Ramsgate, Folkestone, Portsmouth and Southampton all opted to "Leave" whilst 24 areas voted to "Remain", with Brighton and Hove voting most favourably for continued membership, with 68.6% in favour.

Greater London was the only English region which voted to remain in the EU. Around the time of the referendum, a petition calling on London mayor Sadiq Khan to declare London independent from the UK collected tens of thousands of signatures.[148][149] The BBC reported the petition as tongue-in-cheek.[150] Supporters of London's independence argued that London's demographic, culture and values are different from the rest of England, and that it should become a city state similar to Singapore, while remaining an EU member state.[151][152] Spencer Livermore, Baron Livermore, said that London's independence "should be a goal," arguing that a London city-state would have twice the GDP of Singapore.[153] Khan said that complete independence was unrealistic, but demanded devolving more powers and autonomy for London.[154]

Scotland

[edit]

Scotland voted 62% to remain in the European Union, with all 32 council areas returning a majority for remaining (albeit with an extremely narrow margin of 122 votes in Moray).[155] Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said it was "clear that the people of Scotland see their future as part of the European Union" and that Scotland had "spoken decisively" with a "strong, unequivocal" vote to remain in the European Union.[156] The Scottish Government announced on 24 June 2016 that officials would plan for a "highly likely" second referendum on independence from the United Kingdom and start preparing legislation to that effect.[157] Former First Minister Alex Salmond said the vote was a "significant and material change" in Scotland's position within the United Kingdom, and that he was certain his party would implement its manifesto on holding a second referendum.[158] Sturgeon said she will communicate to all EU member states that "Scotland has voted to stay in the EU and I intend to discuss all options for doing so."[6] An emergency cabinet meeting on 25 June 2016 agreed that the Scottish Government would "begin immediate discussions with the EU institutions and other member states to explore all the possible options to protect Scotland's place in the EU."[159]

On 26 June, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon told the BBC that Scotland could attempt to refuse legislative consent for the UK's exit from the European Union,[160] and on 28 June, established a "standing council" of experts to advise her on how to protect Scotland's relationship with the EU.[161] On the same day she made the following statement: "I want to be clear to parliament that whilst I believe that independence is the best option for Scotland – I don’t think that will come as a surprise to anyone – it is not my starting point in these discussions. My starting point is to protect our relationship with the EU."[162] Sturgeon met with EU leaders in Brussels the next day to discuss Scotland remaining in the EU. Afterwards, she said the reception had been "sympathetic", in spite of France and Spain objecting to negotiations with Scotland, but conceded that she did not underestimate the challenges.[163]

Also on 28 June, Scottish MEP Alyn Smith received standing ovations from the European Parliament for a speech ending "Scotland did not let you down, do not let Scotland down."[164] Manfred Weber, the leader of the European People's Party Group and a key ally of Angela Merkel, said Scotland would be welcome to remain a member of the EU.[165] In an earlier Welt am Sonntag interview, Gunther Krichbaum, chairman of the Bundestag's European affairs committee, stated that "the EU will still consist of 28 member states, as I expect a new independence referendum in Scotland, which will then be successful," and urged to "respond quickly to an application for admission from the EU-friendly country."[166]

In a note to the US bank's clients, JP Morgan Senior Western Europe economist Malcolm Barr wrote: "Our base case is that Scotland will vote for independence and institute a new currency" by 2019.[167]

On 15 July, following her first official talks with Nicola Sturgeon at Bute House, Theresa May said that she was "willing to listen to options" on Scotland's future relationship with the European Union and wanted the Scottish government to be "fully involved" with discussions, but that Scotland had sent a "very clear message" on independence in 2014. Sturgeon said she was "very pleased" that May would listen to the Scottish Government, but that it would be "completely wrong" to block a referendum if it was wanted by the people of Scotland.[168][169] Two days later, Sturgeon told the BBC that she would consider holding a referendum for 2017 if the UK began the process of exiting the European Union without Scotland's future being secured.[170] She also suggested it may be possible for Scotland to remain part of the UK while also remaining part of the EU.[171] However, on 20 July, this idea was dismissed by Attorney General Jeremy Wright, who told the House of Commons that no part of the UK had a veto over the Article 50 process.[172]

On 28 March 2017, the Scottish parliament voted 69–59 in favour of holding a new referendum on Scottish Independence,[173] and on 31 March, Nicola Sturgeon wrote to PM May requesting permission to hold a second referendum.

Northern Ireland

[edit]A referendum on Irish unification has been advocated by Sinn Féin, the largest nationalist/republican party in Ireland, which is represented both in the Northern Ireland Assembly and Dáil Éireann in the Republic of Ireland.[174] Northern Ireland's deputy First Minister, Martin McGuinness of Sinn Féin, called for a referendum on the subject following the UK's vote to leave the EU because the majority of the Northern Irish population voted to remain.[175] The First Minister, Arlene Foster of the Democratic Unionist Party, said that Northern Ireland's status remained secure and that the vote had strengthened the union within the United Kingdom.[176] This was echoed by DUP MLA Ian Paisley Jr., who nevertheless recommended that constituents apply for an Irish passport to retain EU rights.[177]

Wales

[edit]

Although Wales voted to leave the European Union, Leanne Wood, the leader of Plaid Cymru suggested that the result had "changed everything" and that it was time to begin a debate about independence for Wales. Sources including The Guardian have noted that opinion polls tend to put the number in favour of Wales seceding from the United Kingdom at 10%, but Wood suggested in a speech shortly after the referendum that attitudes could change following the result: "The Welsh economy and our constitution face unprecedented challenges. We must explore options that haven’t been properly debated until now."[178] On 5 July, a YouGov opinion poll commissioned by ITV Wales indicated that 35% would vote in favour of Welsh independence in the event that it meant Wales could stay in the European Union, but Professor Roger Scully, of Cardiff University's Wales Governance Centre said the poll indicated a "clear majority" against Wales ceasing to be part of the UK: “The overall message appears to be that while Brexit might reopen the discussion on Welsh independence there is little sign that the Leave vote in the EU referendum has yet inclined growing numbers of people to vote Leave in a referendum on Welsh independence from the UK."[179]

Gibraltar

[edit]Spain's foreign minister José Manuel García-Margallo said "It's a complete change of outlook that opens up new possibilities on Gibraltar not seen for a very long time. I hope the formula of co-sovereignty – to be clear, the Spanish flag on the Rock – is much closer than before."[180] Gibraltar's Chief Minister Fabian Picardo however immediately dismissed García-Margallo's remarks, stating that "there will be no talks, or even talks about talks, about the sovereignty of Gibraltar", and asked Gibraltar's citizens "to ignore these noises".[181] This is while he was in talks with Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister of Scotland, to keep Gibraltar in the EU, while remaining British too. He said that "I can imagine a situation where some parts of what is today the member state United Kingdom are stripped out and others remain." Nicola Sturgeon said on the same day that talks were under way with Gibraltar to build a "common cause" on EU membership.[182][183]

Republic of Ireland

[edit]The Republic of Ireland, which shares a land border with the United Kingdom, joined the then European Communities alongside its neighbour on 1 January 1973, and as of 2016, its trade with the UK was worth £840m (€1bn) a week, while as many as 380,000 Irish citizens were employed in the UK. Britain was also a significant contributor towards the 2010 bailout package that was put together in the wake of the banking crisis of the late 2000s. Concerned by the possibility of a British vote to leave the EU, in 2015, Enda Kenny, the Taoiseach of Ireland, established an office to put together a contingency plan in the event of a Brexit vote.[184][185]

On 18 July 2016, Bloomberg News reported that the UK's vote to leave the EU was having a negative impact on the Republic of Ireland, a country with close economic and cultural ties to the UK. Share prices in Ireland fell after the result, while exporters warned that a weaker British currency would drive down wages and economic growth in a country still recovering from the effects of the banking crisis. John Bruton, who served as Taoiseach from 1994 to 1997, and later an EU ambassador to the United States, described Britain's vote to leave the European Union as "the most serious, difficult issue facing the country for 50 years".[184] Nick Ashmore, head of the Strategic Banking Corporation of Ireland argued the uncertainty caused by the result had made attracting new business lenders into Ireland more difficult.[186] However, John McGrane, director general of the British Irish Chamber of Commerce, said the organisation had been inundated with enquiries from British firms wishing to explore the feasibility of basing themselves in a country "with the same language and legal system and with a commitment to staying in the EU".[185]

On 21 July, following talks in Dublin, Kenny and French President François Hollande issued a joint statement saying they "looked forward to the notification as soon as possible by the new British government of the UK's intention to withdraw from the Union" because it would "permit orderly negotiations to begin".[187] Hollande also suggested Ireland should secure a "special situation" in discussions with European leaders during the UK's European withdrawal negotiations.[188]

Racist abuse and hate crimes

[edit]More than a hundred racist abuse and hate crimes were reported in the immediate aftermath of the referendum with many citing the plan to leave the European Union, with police saying there had been a five-fold increase since the vote.[189] On 24 June, a school in Cambridgeshire was vandalised with a sign reading "Leave the EU. No more Polish vermin."[190][191] Following the referendum result, similar signs were distributed outside homes and schools in Huntingdon, with some left on the cars of Polish residents collecting their children from school.[192] On 26 June, the London office of the Polish Social and Cultural Association was vandalised with racist graffiti.[193] Both incidents were investigated by the police.[190][193] Other instances of racism occurred as perceived foreigners were targeted in supermarkets, on buses and on street corners, and told to leave the country immediately.[194] The hate crimes were widely condemned by politicians, the UN and religious groups.[195][196] MEP Daniel Hannan disputed both the accuracy of reporting and connection to the referendum,[197][198] in turn receiving criticism for rejecting evidence.[196]

On 8 July 2016, figures released by the National Police Chiefs' Council indicated there were 3,076 reported hate crimes and incidents across England, Wales and Northern Ireland between 16 and 30 June, compared to 2,161 for the same period in 2015, a 42% increase; the number of incidents peaked on 25 June, when there were 289 reported cases. Assistant Chief Constable Mark Hamilton, the council's lead on hate crime, described the "sharp rise" as unacceptable.[199][200] The figures were reported to have shown the greatest increase in areas that voted strongly to leave.[201]

Post-referendum campaigning

[edit]Petition for a new referendum

[edit]Within hours of the result's announcement, a petition, calling for a second referendum to be held in the event that a result was secured with less than 60% of the vote and on a turnout of less than 75%, attracted tens of thousands of new signatures. The petition had been initiated by William Oliver Healey of the English Democrats on 24 May 2016, when the Remain faction had been leading in the polls, and had received 22 signatures prior to the referendum result being declared.[202][203][204] On 26 June, Healey said that the petition had actually been started to favour an exit from the EU and that he was a strong supporter of the Vote Leave and Grassroots Out campaigns. Healey also said that the petition had been "hijacked by the remain campaign".[205][206] English Democrats chairman Robin Tilbrook suggested those who had signed the petition were experiencing "sour grapes" about the result of the referendum.[207]

By late July it had attracted over 4 million signatures, about one quarter of the total number of remain votes in the referendum and over forty times the 100,000 needed for any petition to be considered for debate in Parliament. As many as a thousand signatures per minute were being added during the day after the referendum vote, causing the website to crash on several occasions.[208][209] Some of the signatories had abstained from voting or had voted leave but regretted their decision, in what the media dubbed "bregret",[210][211] or "regrexit" at the result.[212][213]

No previous government petition had attracted as many signatures, but it was reported that the House of Commons Petitions Committee were investigating allegations of fraud. Chair of that committee, Helen Jones, said that the allegations were being taken seriously, and any signatures found to be fraudulent would be removed from the petition: "People adding fraudulent signatures to this petition should know that they undermine the cause they pretend to support."[202] By the afternoon of 26 June the House of Commons' petitions committee said that it had removed "about 77,000 signatures which were added fraudulently" and that it would continue to monitor the petition for "suspicious activity"; almost 40,000 signatures seemed to have come from the Vatican City, which has a population of under 1,000.[214] Hackers from 4chan claimed that they had added the signatures with the use of automated bots,[215] and that it was done as a prank.[214]

As the Prime Minister made clear in his statement to the House of Commons on 27 June, the referendum was one of the biggest democratic exercises in British history with over 33 million people having their say. The Prime Minister and Government have been clear that this was a once in a generation vote and, as the Prime Minister has said, the decision must be respected. We must now prepare for the process to exit the EU and the Government is committed to ensuring the best possible outcome for the British people in the negotiations.[216]

On 8 July, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office sent an email to all signatories of the petition setting out the government's position. It rejected calls for a second referendum: "Prime Minister and Government have been clear that this was a once in a generation vote and, as the Prime Minister has said, the decision must be respected."[217] On 12 July the Committee scheduled a debate on the petition for 5 September because of the "huge number" of people who had signed it, but stressed that this did not mean it was backing calls for a second referendum.[218] The debate, held in Westminster Hall, the House of Commons' second chamber, does not have the power to change the law; a spokesman for the Committee said that the debate would not pave the way for Parliament to decide on holding a second referendum.[219][220] The petition closed on 26 November 2016, having received 4,150,259 signatures.[221]

BBC political correspondent Iain Watson has argued that since the petition requests a piece of retrospective legislation, it is unlikely to be enacted.[202]

Debate over a second referendum

[edit]David Cameron had previously ruled out holding a second referendum, calling it "a once-in-a-lifetime event".[222][223] However, Jolyon Maugham QC, a barrister specialising in tax law, argued that a second referendum on EU membership could be triggered by one of two scenarios: following a snap general election won by one or more parties standing on a remain platform, or as a result of parliament deciding that circumstances had changed significantly enough to require a fresh mandate. Maugham cited several instances in which a country's electorate have been asked to reconsider the outcome of a referendum relating to the EU, among them the two Treaty of Lisbon referendums held in Ireland, in 2008 and 2009.[224]

Historian Vernon Bogdanor said that a second referendum would be "highly unlikely", and suggested governments would be cautious about holding referendums in future,[225] but argued it could happen if the EU rethought some of its policies, such as those regarding the free movement of workers.[226] Political scientist John Curtice agreed that a change of circumstances could result in another referendum, but said the petition would have little effect.[225] In 2016, BBC legal correspondent Clive Coleman argued that a second referendum was "constitutionally possible [but] politically unthinkable. It would take something akin to a revolution and full-blown constitutional crisis for it to happen".[204] Conservative MP Dominic Grieve, a former Attorney General for England and Wales said that although the government should respect the result of the referendum, "it is of course possible that it will become apparent with the passage of time that public opinion has shifted on the matter. If so a second referendum may be justified."[227] Barristers Belinda McRae and Andrew Lodder argued the referendum "is wrongly being treated as a majority vote for the terms of exit that Britain can negotiate [with] the EU" when the public were not asked about the terms of exiting the EU, so a second referendum would be needed on that issue.[228] Richard Dawkins argued that if a second referendum upheld the result of the first, it would "unite the country behind Brexit".[229] However, political scientist Liubomir K. Topaloff argued that a second referendum would "surely destroy the EU" because the resulting anger of Leave supporters in the UK would spread anti-EU sentiment in other countries.[230]

On 26 June, former prime minister Tony Blair said the option of holding a second referendum should not be ruled out.[231] A week later he suggested the will of the people could change, and that Parliament should reflect that.[232] Alastair Campbell, the Downing Street Director of Communications under Blair called for a second referendum setting out "the terms on which we leave. And the terms on which we could remain".[233] Labour MP David Lammy commented that, as the referendum was advisory, Parliament should vote on whether to leave the EU.[234] On 1 July, Shadow chancellor John McDonnell outlined Labour's vision for leaving the EU, saying that Britain had to respect the decision that was made in the referendum.[235]

Following the first post-referendum meeting of the Cabinet on 27 June, a spokesman for the Prime Minister said that the possibility of a second referendum was "not remotely on the cards. There was a decisive result [in the EU referendum]. The focus of the Cabinet discussion was how we get on and deliver that."[124] Theresa May also ruled out the possibility at the launch of her campaign to succeed Cameron.[76] On 28 June, Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt raised the possibility of a second referendum, but said that it would be about the terms of the UK's exit from the European Union rather than on the issue of EU membership.[236] Labour MP Geraint Davies also suggested that a second referendum would focus on the terms of an exit plan, with a default of remaining in the EU if it were rejected. Citing a poll published in the week after the referendum that indicated as many as 1.1 million people who voted to leave the EU regretted their decision, he tabled an early day motion calling for an exit package referendum.[237]

On 26 June it was reported that Conservative grandee Michael Heseltine was suggesting that a second referendum should take place after Brexit negotiations, pointing to the overwhelming majority in the House of Commons against leaving the EU.[238] On 13 July, Labour leadership candidate Owen Smith said that he would offer a second referendum on the terms of EU withdrawal if elected to lead the party.[62]

The outcome of the referendum was debated by the Church of England's General Synod on 8 July, where Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby ruled out supporting a second referendum.[239] The idea of a second referendum was also rejected by Plaid Cymru leader Leanne Wood, who favoured a general election following negotiations instead.[240] Sammy Wilson, a Democratic Unionist Party MP likened those calling for a second referendum to fascists, saying "They don't wish to have the democratic wishes of the people honoured... They wish to have only their views."[241]

Polls in 2016 and 2017 did not find public support for a second referendum,[242][243] with YouGov polling indicating a slim majority for the first time on 27 July 2018.[244]

The TUC has said that they fear any Brexit deal might harm workers' interests and lead to workers in many industries losing their jobs. Frances O'Grady of the TUC said that unless the government provides a deal that is good for working people, the TUC will strongly "throw our full weight behind a campaign for a popular vote so that people get a say on whether that deal is good enough or not."[245]

Pro-EU activities

[edit]

Pro-EU demonstrations took place in the days following the referendum result. On 24 June, protesters gathered in cities across the UK, including London, Edinburgh and Glasgow. At one demonstration in London hundreds of protesters marched on the headquarters of News UK to protest against "anti-immigration politics".[246] Protesters on bicycles angry at the result attempted to block Boris Johnson's car as he was leaving his home on the morning of 24 June, while campaigners aged 18–25, as well as some teenagers under the age of majority, staged a protest outside Parliament.[247]

On 28 June, up to 50,000 people attended Stand Together, a pro-EU demonstration organised for London's Trafalgar Square, despite the event having been officially cancelled amid safety concerns. The organiser had announced the rally on social media, with a view to bringing "20 friends together", but urged people not to attend as the number of people expressing interest reached 50,000. The meeting was addressed by Liberal Democrat leader Tim Farron before protesters made their way to Whitehall. A similar event in Cardiff was addressed by speakers including Plaid Cymru leader Leanne Wood.[248] On 2 July, around 50,000 demonstrators marched in London to show support for the EU and to demand that Britain continues to co-operate with other European states.[249][250] A similar event was held in Edinburgh outside the Scottish Parliament Building.[251]

On 8 July 2016, and in response to the referendum result, The New European, was launched with an initial print run of 200,000. This is a national weekly newspaper aimed at people who voted to remain in the EU, which its editor felt had not been represented by the traditional media, and remains in print as of December 2017.[252][253][254]

Proposed British Independence Day national holiday

[edit]Some Brexit supporters such as David Davies, Steve Double, William Wragg and Sir David Amess called for the Brexit referendum result on 23 June 2016 to be recognised as British Independence Day and be made a public holiday in the United Kingdom.[255][256][257] The concept was widely used in social media, with the BBC naming it as one of "Five social media trends after Brexit vote".[258][259] With support from Conservative MP Nigel Evans,[260][261] an online petition on the British Parliament government website calling for the date to be "designated as Independence Day, and celebrated annually" reached sufficient signatures to trigger a government response, which stated there were "no current plans to create another public holiday".[262][263][264]

On 5 September 2017, a number of Conservative MPs backed MP Peter Bone's June Bank Holiday (Creation) Bill in the House of Commons, for the Brexit referendum date to be a UK-wide public holiday.[265][255][266] The bill proposes that "June 23 or the subsequent weekday when June 23 falls at a weekend" should serve as a national holiday.[267][268][269]

Official investigations into campaigns

[edit]On 9 May 2016, Leave.EU was fined £50,000 by the British Information Commissioner's Office 'for failing to follow the rules about sending marketing messages': they sent people text messages without having first gained their permission to do so.[270][271]

On 4 March 2017, the Information Commissioner's Office also reported that it was 'conducting a wide assessment of the data-protection risks arising from the use of data analytics, including for political purposes' in relation to the Brexit campaign. It was specified that among the organisations to be investigated was Cambridge Analytica and its relationship with the Leave.EU campaign. The findings are expected to be published sometime in 2017.[272][273]

On 21 April 2017, the Electoral Commission announced that it was investigating 'whether one or more donations – including of services – accepted by Leave.EU was impermissible; and whether Leave.EU's spending return was complete', because 'there were reasonable grounds to suspect that potential offences under the law may have occurred'.[274][273]

Foreign interference

[edit]

In the run up to the Brexit referendum, Prime Minister David Cameron had suggested that Russia "might be happy" with a positive Brexit vote, while the Remain campaign accused the Kremlin of secretly backing a positive Brexit vote.[275] In December 2016, Ben Bradshaw MP claimed in Parliament that it was "highly probable" that Russia had interfered in the Brexit referendum campaign,[276] later calling on the British intelligence service, Government Communications Headquarters (then under Boris Johnson as Foreign Secretary) to reveal the information it had on Russian interference.[277] In April 2017, the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee issued a report stating that Russian and foreign interference in the referendum was probable, including the shutdown of the government voter registration website immediately before the vote.[278]

In May 2017, it was reported by The Irish Times that £425,622 had potentially been donated by sources in Saudi Arabia to the "vote leave" supporting Democratic Unionist Party for spending during the referendum.[279]

Some British politicians accused US President Barack Obama of interfering in the Brexit vote by publicly stating his support for continued EU membership.[280]

See also

[edit]- Brexit

- 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum

- International reactions to the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum

- Brexit and arrangements for science and technology

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "The Brexit vote reveals a country split down the middle", The Economist, 24 June 2016, retrieved 4 July 2016

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (20 July 2016). "Cameron accused of 'gross negligence' over Brexit contingency plans". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ^ "Brexit and the UK's Public Finances" (PDF). Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS Report 116). May 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ The end of British austerity starts with Brexit J. Redwood, The Guardian, 14 April 2016

- ^ a b Sparrow, Andrew; Weaver, Matthew; Oltermann, Philip; Vaughan, Adam; Asthana, Anushka; Tran, Mark; Elgot, Jessica; Watt, Holly; Rankin, Jennifer; McDonald, Henry; Kennedy, Maev; Perraudin, Frances; Neslen, Arthur; O'Carroll, Lisa; Khomami, Nadia; Morris, Steven; Duncan, Pamela; Allen, Katie; Carrell, Severin; Mason, Rowena; Bengtsson, Helena; Barr, Caelainn; Goodley, Simon; Brooks, Libby; Wearden, Graeme; Quinn, Ben; Ramesh, Randeep; Fletcher, Nick; Treanor, Jill; McCurry, Justin; Adams, Richard; Halliday, Josh; Pegg, David; Phipps, Claire; Mattinson, Deborah; Walker, Peter (24 June 2016). "Brexit: Nicola Sturgeon says second Scottish referendum 'highly likely'". The Guardian.

- ^ Jill Trainor (5 July 2016). "Bank of England releases £150bn of lending and warns on financial stability". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ "Britain's financial sector reels after Brexit bombshell". Reuters. 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Ratings agencies downgrade UK credit rating after Brexit vote". BBC News. 27 June 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ Buttonwood (27 June 2016). "Markets after the referendum – Britain faces Project Reality". The Economist. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Post-Brexit rebound sees FTSE setting biggest weekly rise since 2011". London. Reuters. 1 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ "FTSE 100 rises to 11-month high". BBC News. 11 July 2016.

- ^ "FTSE 100 hits one-year high and FTSE 250 erases post-Brexit losses as UK economy grows by 0.6pc". The Daily Telegraph. 27 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ "S&P 500 hits record high for first time since '15". Financial Times. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Brexit after EU referendum: UK to leave EU and David Cameron quits". BBC News.

- ^ McGeever, Jamie (7 July 2016). "Sterling's post-Brexit fall is biggest loss in a hard currency". Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ Duarte De Aragao, Marianna (8 July 2016). "Pound Overtakes Argentine Peso to Become 2016's Worst Performer". Bloomberg News. Bloomberg. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Sheffield, Hazel (8 July 2016). "Pound sterling beats Argentine peso to become 2016's worst performing currency". The Independent. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Osborne, Alistair (9 July 2016). "Own goal is gift to Argentina". The Times. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Brexit: Here are the three major winners from a weak pound right now E. Shing, International Business Times, 6 July 2016

- ^ Swinford, Steven (10 August 2016). "Britain could be up to £70billion worse off if it leaves the Single Market after Brexit, IFS warns". Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Claim 'hard Brexit' could cost UK£10bn in tax". Financial Times. 4 October 2016. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ "Banks poised to relocate out of UK over Brexit, BBA warns". BBC News. 23 October 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ "Bank of England Economist: Brexit Predictions Were Wrong". Fox News (from the Associated Press). 6 January 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ Inman, Phillip (5 January 2017). "Chief Economist of Bank of England Admits Errors in Brexit Forecasting". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ Swinford, Steven (6 January 2017). "Bank of England Admits 'Michael Fish' Moment with Dire Brexit Predictions". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ 'The Brexit vote is starting to have major negative consequences' – experts debate the data The Guardian

- ^ Wood, Zoe (26 June 2016). "Firms plan to quit UK as City braces for more post-Brexit losses". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Osborne: UK economy in a position of strength". BBC News. 27 June 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

George Osborne has said the UK is ready to face the future "from a position of strength" and indicated there will be no immediate emergency Budget.

- ^ Dewan, Angela; McKirdy, Euan (27 June 2016). "Brexit: UK government shifts to damage control". CNN. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

Not since World War II has Britain faced such an uncertain future.

- ^ "Philip Hammond: Financial markets 'rattled' by Leave vote". BBC News. 14 July 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Sheffield, Hazel (14 July 2016). "Brexit will plunge the UK into a recession in the next year, BlackRock says". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Rodionova, Zlata (18 July 2016). "UK faces short recession as Brexit uncertainty hits house prices, consumer spending and jobs, EY predicts". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Archived from the original on 18 July 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ De Peyer, Robin (18 July 2016). "Britain 'set for recession' as Richard Buxton calls leaving EU 'horrible'". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Elliott, Larry (19 July 2016). "IMF cuts UK growth forecasts following Brexit vote". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Meakin, Lucy; Ward, Jill (20 July 2016). "BOE Sees No Sharp Slowing Yet Even as Brexit Boosts Uncertainty". Bloomberg News. Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ Ralph, Alex (2 September 2016). "Rally rewards bravery in the face of Project Fear". The Times. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ Katie Allen (22 November 2016). "Brexit economy: inflation surge shows impact of vote finally beginning to bite | Business". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "IMF raises forecast for UK economic growth to 2% in 2017". Sky News. 18 April 2017.

- ^ "Brexit: David Cameron to quit after UK votes to leave EU". BBC News. 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Brexit: David Cameron to quit after UK votes to leave EU". BBC New. 24 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "New Tory leader 'should be in place by 9 September'". BBC News. 28 June 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Rowena Mason (25 June 2016). "Theresa May emerges as 'Stop Boris' Tory leadership candidate". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Conservative leadership: Andrea Leadsom emerges as pro-Leave rival to Theresa May as Michael Gove fades". 2 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2 July 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Theresa May v Andrea Leadsom in Conservative leader race". BBC News.

- ^ "PM-in-waiting Theresa May promises 'a better Britain'". BBC News. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ MacLellan, Kylie (13 July 2016). "After winning power, Theresa May faces Brexit divorce battle". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Labour 'Out' Votes Heap Pressure on Corbyn".

- ^ "Brexit after EU referendum: UK to leave EU and David Cameron quits". BBC News. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Corbyn office 'sabotaged' EU Remain campaign". BBC News. 26 June 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ Asthana A; Syal, R. (26 June 2016). "Labour in crisis: Tom Watson criticises Hilary Benn sacking". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ "Jeremy Corbyn's new-look shadow cabinet". The Telegraph. London. 27 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Corbyn told he faces leadership fight as resignations continue". BBC News. 27 June 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

Deputy Labour leader Tom Watson has told Jeremy Corbyn he has "no authority" among Labour MPs and warned him he faces a leadership challenge.

- ^ "Jeremy Corbyn Loses Vote of No Confidence". Sky News. 28 June 2016. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Holden, Michael; Piper, Elizabeth (28 June 2016). "EU leaders tell Britain to exit swiftly, market rout halts". Reuters. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

the confidence vote does not automatically trigger a leadership election and Corbyn, who says he enjoys strong grassroots support, refused to quit. 'I was democratically elected leader of our party for a new kind of politics by 60 percent of Labour members and supporters, and I will not betray them by resigning,' he said.

- ^ Asthana, Anushka (28 June 2016). "Jeremy Corbyn suffers heavy loss in Labour MPs confidence vote". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Wilkinson, Michael (29 June 2016). "David Cameron and Ed Miliband tell Jeremy Corbyn to resign as Tom Watson says he will not contest Labour leadership leaving Angela Eagle as the unity candidate". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "Corbyn to face Labour leadership challenge from Angela Eagle". BBC. 29 June 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "Labour leadership: Angela Eagle says she can unite the party". BBC News. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ Grice, Andrew (19 July 2016). "Labour leadership election: Angela Eagle pulls out of contest to allow Owen Smith straight run at Jeremy Corbyn". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ "EU vote: Where the cabinet and other MPs stand". BBC News. 22 June 2016.

- ^ a b Asthana, Anushka; Stewart, Heather (13 July 2016). "Owen Smith to offer referendum on Brexit deal if elected Labour leader". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Cornock, David (21 July 2016). "Owen Smith on Corbyn, leadership, devolution and Brexit". BBC Wales. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

said voters backed Brexit because they didn't feel the Labour Party stood up for them,

- ^ a b "Lib Dems to pledge British return to EU in next general election". 26 June 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (19 July 2016). "Liberals, celebrities and EU supporters set up progressive movement". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ Shead, Sam (24 July 2016). "Paddy Ashdown has launched a tech-driven political startup called More United that will crowdfund MPs across all parties". Business Insider. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ "Our Principles". More Together. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ "UKIP leader Nigel Farage stands down". BBC News. 4 July 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Nigel Farage steps back in at UKIP as Diane James quits". BBC News. 5 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ Fisher, Lucy (28 November 2016). "Putin and Assad are on our side, claims new Ukip leader". The Times.

- ^ Crisis looms for social policy agenda as Brexit preoccupies Whitehall The Guardian

- ^ Rebel MPs form cross-party group to oppose hard Brexit The Guardian

- ^ Tuft, Ben. "When will the next UK General Election be held?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 August 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ "The EU referendum reveals a nation utterly divided. An early general election is the only answer". The Daily Telegraph. 24 June 2016.

- ^ Vince Chadwick (4 July 2016). "Andrea Leadsom: EU citizens can stay in UK". politico.eu. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ a b Stone, Jon (30 June 2016). "Theresa May rules out early general election or second EU referendum if she becomes Conservative leader". The Independent. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ Daily Politics, BBC2, 11 July 2016

- ^ "David Cameron's last full day as PM and Labour leadership". BBC News. 12 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Theresa May's surprise General Election statement in full". 18 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ The Brexit resistance: ‘It’s getting bigger all the time’ The Guardian

- ^ Brown, Gordon (29 June 2016). "The key lesson of Brexit is that globalisation must work for all of Britain". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ Joe Watts (28 October 2016). "Brexit: Tony Blair says there must be a second vote on UK's membership of EU". The Independent. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ "Tony Blair 'to help the UK's politically homeless'". BBC News. 24 November 2016.

- ^ What British people think about Brexit now BBC 18 September 2018

- ^ "Leading Tory Brexiter says 'free movement of Labour' should continue after Brexit". The Independent. 25 June 2016. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ "Tory Brexiter Daniel Hannan: Leave campaign never promised "radical decline" in immigration". New Statesman. 25 June 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.