Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

| |

| |

| Established | 28 November 1885 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 52°28′49″N 1°54′13″W / 52.48028°N 1.90361°W |

| Collection size | c. 800,000 objects[1] |

| Visitors | 644,100 (2019)[2] |

| Website | birminghammuseums.org.uk |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Designated | 25 April 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1210333 |

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BM&AG) is a museum and art gallery in Birmingham, England. It has a collection of international importance covering fine art, ceramics, metalwork, jewellery, natural history, archaeology, ethnography, local history and industrial history.[3]

The museum/gallery is run by Birmingham Museums Trust, the largest independent museums trust in the United Kingdom, which also runs eight other museums around the city.[4] Entrance to the Museum and Art Gallery is free, but some major exhibitions in the Gas Hall incur an entrance fee.

History

[edit]In 1829, the Birmingham Society of Artists created a private exhibition building in New Street, Birmingham while the historical precedent for public education around that time produced the Factory Act 1833, the first instance of Government funding for education.

The Museums Act 1845 "[empowered] boroughs with a population of 10,000 or more to raise a 1/2d for the establishment of museums."[5] In 1864, the first public exhibition room, was opened when the Society and other donors presented 64 pictures as well as the Sultanganj Buddha to Birmingham Council and these were housed in the Free Library building but, due to lack of space, the pictures had to move to Aston Hall.[6] Joseph Henry Nettlefold (1827–1881) bequeathed twenty-five pictures by David Cox to Birmingham Art Gallery on the condition it opened on Sundays.[7]

In June 1880, local artist Allen Edward Everitt accepted the post of honorary curator of the Free Art Gallery, a municipal institution which was the forerunner of the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.[8]

Jesse Collings, Mayor of Birmingham 1878–79, was responsible for free libraries in Birmingham and was the original proponent of the Birmingham Art Gallery. A gift of £10,000 (equivalent to £1,100,000 in 2020) made by Sir Richard and George Tangye started a new drive for an art gallery and, in 1885, following other donations and £40,000 from the council, the Prince of Wales officially opened the new gallery on Saturday 28 November 1885.[6][9] The Museum and Art Gallery occupied an extended part of the Council House above the new offices of the municipal Gas Department (which in effect subsidised the venture thus circumventing the Public Libraries Act 1850 which limited the use of public funds on the arts). The building was designed by Yeoville Thomason.[10] The metalwork for the new building (and adjoining Council House) was by the Birmingham firm of Hart, Son, Peard & Co. and extended to both the interior and exterior including the distinctive cast-iron columns in the main gallery space for the display of decorative art.[11] The lofty portico, surmounted by a pediment by Francis John Williamson, representing an allegory of Birmingham contributing to the fine arts, was together with the clock-tower considered the "most conspicuous features" of the exterior upon its opening.[12] By 1900 the collection, especially its contemporary British holdings, was deemed by the Magazine of Art to be "one of the finest and handsomest" in Britain.[13]

Until 1946, when property taxes were voted towards acquisitions, the museum relied on the generosity of private individuals.[6] John Feeney provided £50,000 to provide a further gallery.

Seven galleries had to be rebuilt after being bombed in 1940.[6] Immediately after World War II "Mighty Mary" Mary Woodall (1901–1988) was appointed keeper of art under director, Trenchard Cox. Woodall and Cox, through their links to the London art world, were able to attract exhibitions, much publicity and donations to the gallery. In 1956, Woodall replaced Cox when the latter became Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum.[14] John Woodward (1921–1988) was Keeper of Art from 1956 to 1964.

In 1951, the Museum of Science and Industry, Birmingham was incorporated into BM&AG. In 2001, the Science Museum closed with some exhibits being transferred to Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum, which was operated by the independent Thinktank Trust that has since become part of Birmingham Museums Trust.

The main entrance is located in Chamberlain Square below the clock-tower known locally as "Big Brum". The entrance hall memorial reads 'By the gains of Industry we promote Art'.[6] The Extension Block has entrances via the Gas Hall in Edmund Street and Great Charles Street. Waterhall, the original gas department, has its own entrance on Edmund Street.

In October 2010, the Waterhall closed as a BM&AG gallery as a result of a £1.5m cut to Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery's budget in 2010–11. The last BM&AG exhibition that took place in the Waterhall at that time was the Steve McCurry retrospective that ran from 26 June to 17 October 2010. The Waterhall and the Gas Hall have reopened for exhibitions throughout the year.

BM&AG, formerly managed by Birmingham City Council, is now, with Thinktank, part of Birmingham Museums Trust.

Due to the global pandemic, the museum closed in October 2020. The museum remained closed throughout 2021 as part of a project to rewire the Council complex that houses the museum. The museum partially reopened in April 2022 with a number of pop-up exhibitions. It will close again in December 2022 ahead of a full reopening expected in 2024.[15] The gallery's Round Room, Industrial Gallery, and Bridge Gallery reopened on 24 October 2024, as did the tearoom and shop. [16]

Art Gallery collection highlights

[edit]-

Ford Madox Brown,

The Last of England -

William Holman Hunt,

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple -

Frederick Sandys, Morgan le Fay, 1864

-

Frederick Sandys,

Medea -

Benedetto Gennari II,

The Holy Family -

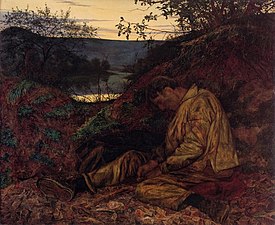

Arthur Hughes

A Christmas Carol at Bracken Dene

Paintings

[edit]The Art Gallery is most noted for its extensive collections of paintings ranging from the 14th to the 21st century. They include works by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the world's largest collection of works by Edward Burne-Jones. Notable painters in oil include the following:

- English School

- Constable, John – 2 paintings;[17][18]

- Cox, David – 11 paintings;[19]

- Gainsborough, Thomas – 3 paintings;[20]

- Hogarth, William – 2 paintings;

- Landseer, Sir Edwin – 1 painting;

- Lely, Peter – 2 paintings;

- Turner, J. M. W. – 1 painting;

- Bacon, Francis – 1 painting;

- Spencer, Stanley – 3 paintings;

- Lanyon, Peter – 1 painting;[21]

- Heron, Patrick – 1 painting;

- Jones, Allen – 1 painting;[22]

Paintings from the Dutch School include a painting each from Jan van Goyen and Willem van de Velde the Younger.

- Flemish School

- Christus, Petrus – 1 painting;

- Rubens, Peter Paul – 1 painting;

- French School

- Dufrénoy, Georges – 1 painting;

- Dughet, Gaspard – 1 painting;

- Gellée, Claude – 2 painting;

- Impressionists

- Degas, Edgar – 1 painting;[23]

- Pissarro, Camille – 1 painting;[24]

- Renoir, Pierre-Auguste – 1 painting;[25]

- German School

- Zoffany, Johan – 1 painting;

- Italian School

- Batoni, Pompeo – 1 painting;

- Bellini, Giovanni – 1 painting;[26]

- Botticelli, Sandro – 1 painting;[27]

- Canaletto, (Giovanni Antonio Canal) – 2 paintings;[28][29]

- Crespi, Giuseppe – 1 painting;

- Dolci, Carlo – 1 painting;

- il Garofalo, Benvenuto Tisio – 1 painting;

- Gentileschi, Orazio – 1 painting;[30]

- Guardi, Francesco – 1 painting;

- Guercino, (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) – 1 painting;

- Martini, Simone – 1 painting;

- Reni, Guido – 1 painting;

- Rosa, Salvator – 1 painting;

- Schiavone, Andrea – 1 painting;

- Strozzi, Bernardo – 1 painting;

- Spanish School

- Murillo, Bartolomé-Esteban – 1 painting.

Antiquities

[edit]The collection of antiquities includes coins from ancient times through to the Middle Ages, artefacts from Ancient India and Central Asia, Ancient Cyprus and Ancient Egypt. The museum also holds 28 pieces of Nimrud ivories from the British School of Archaeology in Iraq.[31] There is material from Classical Greece, the Roman Empire and Latin America. There is also mediaeval material, much of which is now on display in The Birmingham History Galleries, a permanent exhibition on the third floor of the museum.

In November 2014, a dedicated gallery was opened to display the Staffordshire Hoard. Discovered in the nearby village of Hammerwich in 2009, it was the largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold ever found.

In respect of local and industrial history, the tower of the Birmingham HP Sauce factory was a famous landmark alongside the Aston Expressway which was demolished in the summer of 2007.[32] The giant logo from the top of the tower is now in the collection of the Museum.

Gallery

[edit]-

Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

-

Birmingham from the Dome of St Philip's Church by Samuel Lines

-

The Blind Girl by John Everett Millais

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Birmingham Museums Trust Collection". Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Fisher, Mark (2005). "Barber Institute of Fine Arts". Britain's Best Museums and Galleries: From the Greatest Collections to the Smallest Curiosities. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 205–207. ISBN 0-14-101960-3.

- ^ "West Mids accountants appointed by largest independent museums trust". Commercial News Media. 22 July 2013. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ Kelly & Kelly (1977), p. 77.

- ^ a b c d e 'Economic and Social History: Social History since 1815', A History of the County of Warwick: VII The City of Birmingham (1964), pp. 223–45. Feeney Archived 16 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine (accessed: 30 January 2008).

- ^ Barbara M. D. Smith, 'Nettlefold, Joseph Henry (1827–1881)', rev. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ W. J. Harrison, 'Everitt, Allen Edward (1824–1882)', rev. Stephen Wildman, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ "Death of Sir Richard Tangye" (PDF). New York Times. 15 October 1906. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ Historic England & 1210333.

- ^ 'The Ornamental Ironwork of the Birmingham Council House and Art Galleries', The Architect, 27 November 1885, pp. 8–9.

- ^ 'New Public Buildings in Birmingham', The Builder, 5 December 1885, p. 786.

- ^ 'The Chronicle of Art — May: Birmingham Art Gallery', Magazine of Art, May 1899, p. 332.

- ^ Kenneth Garlick, 'Woodall, Mary (1901–1988)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004.

- ^ "Birmingham's Museum and Art Gallery reopens for Commonwealth Games". BBC News. 28 April 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ title=Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery is set to reopen | work=BBC News | url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cvg3g4rnq4zo

- ^ "Oil Painting – Study of Clouds – Evening, August 31st, 1822. – Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre". Bmagic.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Harwich Lighthouse by John Constable at Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery Prints". Bmagprints.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery". Bmagprints.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Birmingham Museums and art Gallery : Search Results : Gainsborough". Bmagic.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Oil Painting – Offshore – Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre". Bmagic.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ [1] Archived 22 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Oil Painting – A Roman Beggar Woman – Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre". Bmagic.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Oil Painting – Le Pont Boieldieu à Rouen, Soleil Couchant [The Pont Boieldieu at Sunset] – Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre". Bmagic.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Oil Painting – St Tropez, France – Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre". Bmagic.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Oil Painting – Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints and Donor – Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre". Bmagic.org.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Oil Painting – The Descent of the Holy Ghost – Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre". Bmagic.org.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Oil Painting – Warwick Castle, East Front from the Courtyard – Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre". Bmagic.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery". Bmagprints.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Oil Painting – Rest on the Flight into Egypt – Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre". Bmagic.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Horry, Ruth A (2015). "Conserving Birmingham Museum's Nimrud ivories". Oracc. University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "UK | England | West Midlands | Demolition of HP factory begins". BBC News. 2 July 2007. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- All About Victoria Square, Joe Holyoak, The Victorian Society Birmingham Group, ISBN 0-901657-14-X.

- By the Gains of Industry – Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery 1885–1985, Stuart Davies, ISBN 0-7093-0131-6.

- Public Sculpture of Birmingham including Sutton Coldfield, George T. Noszlopy, edited Jeremy Beach, 1998, ISBN 0-85323-692-5.

- Historic England. "Council House, City Museum and Art Gallery and Council House extension (1210333)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 May 2006.

Further reading

[edit]- John Alfred Langford, The Birmingham Free Libraries, the Shakespere Memorial Library, and the Art Gallery (Hall & English, 1871).

External links

[edit]- BM&AG website

- Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource Archived 29 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine Over 2,000 Pre-Raphaelite images

- BM&AG collection online

- Oil paintings from BM&AG on the BBC Your Paintings website

- Paintings Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine from the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery on VADS

- Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery within Google Arts & Culture

- Art museums and galleries established in 1885

- 1885 establishments in England

- Collection of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

- Art museums and galleries in Birmingham, West Midlands

- Archaeological museums in England

- City museums in the United Kingdom

- Local museums in the West Midlands (county)

- Grade II* listed buildings in Birmingham

- Grade II listed museum buildings

- Birmingham Museums Trust