Basolateral amygdala

| Basolateral amygdala | |

|---|---|

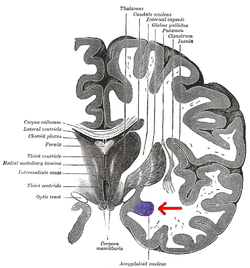

Coronal section of brain through intermediate mass of third ventricle. Amygdala is shown in purple. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Amygdala |

| Identifiers | |

| Acronym(s) | BL |

| NeuroNames | 244 |

| NeuroLex ID | BIRNLEX:2679 |

| FMA | 84609 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The basolateral amygdala, or basolateral complex, or basolateral nuclear complex consists of the lateral, basal and accessory-basal nuclei of the amygdala.[1] The lateral nuclei receives the majority of sensory information, which arrives directly from the temporal lobe structures, including the hippocampus and primary auditory cortex. The basolateral amygdala also receives dense neuromodulatory inputs from ventral tegmental area (VTA),[2][3] locus coeruleus (LC),[4] and basal forebrain,[5] whose integrity are important for associative learning. The information is then processed by the basolateral complex and is sent as output to the central nucleus of the amygdala. This is how most emotional arousal is formed in mammals.[6]

Function

[edit]The amygdala has several different nuclei and internal pathways; the basolateral complex (or basolateral amygdala), the central nucleus, and the cortical nucleus are the most well-known. Each of these has a unique function and purpose within the amygdala.

Fear response

[edit]The basolateral amygdala and nucleus accumbens shell together mediate specific Pavlovian-instrumental transfer, a phenomenon in which a classically conditioned stimulus modifies operant behavior.[7][8] One of the main functions of the basolateral complex is to stimulate the fear response. The fear system is intended to avoid pain or injury. For this reason the responses must be quick, and reflex-like. To achieve this, the “low-road” or a bottom-up process is used to generate a response to stimuli that are potentially hazardous. The stimulus reaches the thalamus, and information is passed to the lateral nucleus, then the basolateral system, and immediately to the central nucleus where a response is then formed. There is no conscious cognition involved in these responses. Other non-threatening stimuli are processed via the “high road” or a top-down form of processing.[9] In this case, the stimulus input reaches the sensory cortex first, leading to more conscious involvement in the response. In immediately threatening situations, the fight-or-flight response is reflexive, and conscious thought processing doesn’t occur until later.[10]

An important process that occurs in basolateral amygdala is consolidation of cued fear memory. One proposed molecular mechanism for this process is collaboration of M1-Muscarinic receptors, D5 receptors and beta-2 adrenergic receptors to redundantly activate phospholipase C, which inhibits the activity of KCNQ channels[11] that conduct inhibitory M current.[12] The neuron then becomes more excitable and the consolidation of memory is enhanced.[11]

Pain memory

[edit]Distinct ensembles of neurons within the basolateral amygdala play a role in encoding associative memories and the response to painful stimuli.[13] The ensemble activated in response to noxious stimuli are of particular interest for targeting treatments of chronic pain and cold allodynia. When neurons within this ensemble are silenced in a rodent model the affective component of pain is essentially erased, while a robust reflex response is maintained.[14] This is thought to implicate the basolateral amygdala in assigning a “pain tag” to valence information which may intrinsically encode that there is a priority to engage in pain-protective behaviors.

References

[edit]- ^ McDonald, AJ (2020). "Functional neuroanatomy of the basolateral amygdala: Neurons, neurotransmitters, and circuits". Handbook of behavioral neuroscience. 26: 1–38. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-815134-1.00001-5. PMC 8248694. PMID 34220399.

- ^ Mingote S, Chuhma N, Kusnoor SV, Field B, Deutch AY, Rayport S (December 2015). "Functional Connectome Analysis of Dopamine Neuron Glutamatergic Connections in Forebrain Regions". The Journal of Neuroscience. 35 (49): 16259–16271. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1674-15.2015. PMC 4682788. PMID 26658874.

- ^ Tang W, Kochubey O, Kintscher M, Schneggenburger R (May 2020). "A VTA to Basal Amygdala Dopamine Projection Contributes to Signal Salient Somatosensory Events during Fear Learning". The Journal of Neuroscience. 40 (20): 3969–3980. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1796-19.2020. PMC 7219297. PMID 32277045.

- ^ Giustino TF, Maren S (2018). "Noradrenergic Modulation of Fear Conditioning and Extinction". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 12: 43. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00043. PMC 5859179. PMID 29593511.

- ^ Crouse RB, Kim K, Batchelor HM, Girardi EM, Kamaletdinova R, Chan J, et al. (September 2020). Hill MN, Colgin LL, Lovinger DM, McNally GP (eds.). "Acetylcholine is released in the basolateral amygdala in response to predictors of reward and enhances the learning of cue-reward contingency". eLife. 9: e57335. doi:10.7554/eLife.57335. PMC 7529459. PMID 32945260.

- ^ Baars BJ, Gage NM (2010). Cognition, Brain, and Consciousness: introduction to cognitive neuroscience (second ed.). Burlington MA: Academic Press.

- ^ Cartoni E, Puglisi-Allegra S, Baldassarre G (November 2013). "The three principles of action: a Pavlovian-instrumental transfer hypothesis". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 7: 153. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00153. PMC 3832805. PMID 24312025.

- ^ Salamone JD, Pardo M, Yohn SE, López-Cruz L, SanMiguel N, Correa M (2016). "Mesolimbic Dopamine and the Regulation of Motivated Behavior". Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 27: 231–257. doi:10.1007/7854_2015_383. ISBN 978-3-319-26933-7. PMID 26323245.

Considerable evidence indicates that accumbens DA is important for Pavlovian approach and Pavlovian-to-instrumental transfer [(PIT)] ... PIT is a behavioral process that reflects the impact of Pavlovian-conditioned stimuli (CS) on instrumental responding. For example, presentation of a Pavlovian CS paired with food can increase output of food-reinforced instrumental behaviors, such as lever pressing. Outcome-specific PIT occurs when the Pavlovian unconditioned stimulus (US) and the instrumental reinforcer are the same stimulus, whereas general PIT is said to occur when the Pavlovian US and the reinforcer are different. ... More recent evidence indicates that accumbens core and shell appear to mediate different aspects of PIT; shell lesions and inactivation reduced outcome-specific PIT, while core lesions and inactivation suppressed general PIT (Corbit and Balleine 2011). These core versus shell differences are likely due to the different anatomical inputs and pallidal outputs associated with these accumbens subregions (Root et al. 2015). These results led Corbit and Balleine (2011) to suggest that accumbens core mediates the general excitatory effects of reward-related cues. PIT provides a fundamental behavioral process by which conditioned stimuli can exert activating effects upon instrumental responding

- ^ Breedlove S, Watson N (2013). Biological Psychology: an introduction to behavioral cognitive, and clinical neuroscience (Seventh ed.). Sunderland: MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.

- ^ Smith C, Kirby L (2001). "Toward delivering on the promise of appraisal theory.". In Scherer KR, Schorr A, Johnstone T (eds.). Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Young MB, Thomas SA (January 2014). "M1-muscarinic receptors promote fear memory consolidation via phospholipase C and the M-current". The Journal of Neuroscience. 34 (5): 1570–1578. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1040-13.2014. PMC 3905134. PMID 24478341.

- ^ Schroeder BC, Hechenberger M, Weinreich F, Kubisch C, Jentsch TJ (August 2000). "KCNQ5, a novel potassium channel broadly expressed in brain, mediates M-type currents". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (31): 24089–24095. doi:10.1074/jbc.M003245200. PMID 10816588.

- ^ Grewe BF, Gründemann J, Kitch LJ, Lecoq JA, Parker JG, Marshall JD, et al. (March 2017). "Neural ensemble dynamics underlying a long-term associative memory". Nature. 543 (7647): 670–675. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..670G. doi:10.1038/nature21682. PMC 5378308. PMID 28329757.

- ^ Corder G, Ahanonu B, Grewe BF, Wang D, Schnitzer MJ, Scherrer G (January 2019). "An amygdalar neural ensemble that encodes the unpleasantness of pain". Science. 363 (6424): 276–281. doi:10.1126/science.aap8586. PMC 6450685. PMID 30655440.