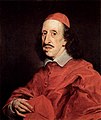

Giovanni Battista Gaulli

Giovanni Battista Gaulli | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, c. 1667 | |

| Born | Giovanni Battista Gaulli 8 May 1639 Genoa, Republic of Genoa |

| Died | 2 April 1709 (aged 69) Rome, Papal States |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Baroque |

Giovanni Battista Gaulli (8 May 1639 – 2 April 1709), also known as Baciccio or Baciccia (Genoese nicknames for Giovanni Battista), was an Italian Baroque painter working in the High Baroque and early Rococo periods. He is best known for his grand illusionistic vault frescos in the Church of the Gesù in Rome. His work was influenced by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Biography

[edit]Gaulli was born in Genoa, where his parents died from the plague of 1654. He initially apprenticed with Luciano Borzone.[1] In the mid-17th century, Gaulli's Genoa was a cosmopolitan Italian artistic center open to both commercial and artistic enterprises from north European countries, including countries with non-Catholic populations such as England and the Dutch provinces. Painters such as Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck stayed in Genoa for a few years. Gaulli's earliest influences would have come from an eclectic mix of these foreign painters and other local artists including Valerio Castello, Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, and Bernardo Strozzi, whose warm palette Gaulli adopted. In the 1660s, he experimented with the cooler palette and linear style of Bolognese classicism.

He was first noticed by the Genoese merchant of artworks, Pellegrino Peri, who was living in Rome. Peri introduced him to Gianlorenzo Bernini, who promoted him. He found patrons among the Genoese Giovanni Paolo Oliva, a prominent Jesuit.[2] In 1662, he was accepted into the Roman artists' guild, the Accademia di San Luca (Academy of Saint Luke), where he was to later hold several offices. The next year, he received his first public commission for an altarpiece, in the church of San Rocco, Rome. He received many private commissions for mythological and religious works.

From 1669, however, after a visit to Parma, Correggio's frescoed dome-ceiling in the cathedral of Parma, Gaulli's painting took on a more painterly (less linear) aspect, and the composition, organized di sotto in su ("from below looking up"), would influence his later masterpiece. At his height, Gaulli was one of Rome's most esteemed portrait painters. Gaulli is not well known for any other medium but paint, though many drawings in many media have survived. All are studies for paintings. Gaulli died in Rome, shortly after 26 March 1709, probably 2 April.

Church of the Gesù frescoes

[edit]

In the first half of the 17th century, two counter-reformation "mother" churches (Sant'Andrea of the Theatines and the Chiesa Nuova of the Oratorians) had been extensively decorated. This was not true for the two large Jesuit churches in Rome, which, while rich in marble and stone, remained artistically barren by the mid-17th century. This void would have been particularly evident for Il Gesù with its cavernous blank plaster nave ceiling.

In 1661, the election of a new General of the Jesuit order, Gian Paolo Oliva, advanced the decoration. A new inductee into the order, the French Jacques Courtois (also known as Giacomo Borgognone) had become a respected painter and was the main candidate for its decoration. Oliva and the leader of the main patron family, the Duke of Parma, Ranuccio II Farnese whose uncle Cardinal Alessandro Farnese had endowed the construction of the church, began negotiating whether Borgognone should decorate the vault. Oliva wanted his fellow Jesuit for the commission, yet other prominent names such as Maratta, Ferri, and Giacinto Brandi were suggested. Ultimately, with Bernini's persuasive support and likely strong guidance thereafter, Oliva awarded the prestigious commission to the mere 22-year-old Gaulli. This choice may have been somewhat controversial, since Gaulli's naked figures recently frescoed in the pendentives for Sant'Agnese in Agone had offended some eyes, and, as had happened to Michelangelo's Sistine chapel altar frescoes, had required repainting to impose painted clothes.[3]

Gaulli decorated the entire dome including lantern and pendentives, central vault, window recesses, and transepts' ceilings. The original contract stipulated the dome was to be completed in two years, and the remainder by the end of ten years. If it met the approval of a panel, Gaulli was to be paid 14,000 scudi plus expenses. Gaulli's main vault fresco was unveiled on Christmas Eve, 1679. After this, he continued frescoing of the vaults of the tribune and other areas in the church until 1685.[4]

Gaulli's program for the nave was likely heavily overseen by Oliva and Bernini; though it is not clear how much all three contributed and whether they all shared the same philosophy. During this time, Bernini supposedly espoused some quietist teachings of the Spanish priest Miguel de Molinos, who was later condemned as heretical in no small part due to Jesuit efforts. Molinos proposed that God was accessible internally through an individual experience, while the Jesuits saw the church and clergy as an essential intermediary for access to Christ's salvation. Thus Oliva would have likely asked Gaulli to memorialize the role of frequently-martyred Jesuits as the apostolic shock troops in heretical and pagan societies, leading the charge of the papal Counter-Reformation. Ultimately, just as Bernini approved of the intermixing fresco and plaster in this new plastic conception, Gaulli blends these ideas in a fashion ultimately acceptable to his patron.

Gaulli's nave masterpiece, the Triumph of the Name of Jesus (also known as the Worship, Adoration, or Triumph of the Holy Name of Jesus), is an allegory of the work of the Jesuits that envelops worshippers (or observers) below into the whirlwind of devotion. Swirling figures in the dark distal (entry) border of the composition frame base the open sky, ever rising upward toward a celestial vision of infinite depth.[5] The light from Jesus' name - IHS - and symbol of the Jesuit order is gathered by patrons and saints above the clouds; while in the darkness below, a fusillade of brilliance scatters heretics, as if smitten by blasts of the Last Judgment.[6] The great theatrical effect here inspired and developed under his mentor, prompted critics to label Gaulli a "Bernini in paint" or a "mouthpiece of Bernini's ideas".[7]

Gaulli's frescoes were a tour-de-force in illusionary painting, depicting the church's roof opens up above the viewer (and that the panorama is viewed in true perspective di sotto in su, similar to Correggio's frescoed dome ceiling depicting the Assumption of the Virgin or to Cortona's grand allegory at the Palazzo Barberini. Gaulli's ceiling is a masterpiece of quadratura (architectural illusionism) combining stuccoed and painted figures and architecture. Bernini's pupil Antonio Raggi provided the stucco figures, and from the nave floor, it is difficult to distinguish painted from stucco angels. The figural composition spill over the frame's edges which only heightens the illusion of the faithful rising miraculously toward the light above.

Later work and legacy

[edit]A series of such ceilings were painted in the naves of Roman churches during the last three decades of the 17th century, including Andrea Pozzo's massive allegory at the other Roman Jesuit church, Sant'Ignazio, as well as Domenico Maria Canuti's and Enrico Haffner's Apotheosis at Santi Domenico e Sisto. In the 18th century, Tiepolo and others continued quadratura in the grand manner. But as the High Baroque movement evolved into the more playful Rococo, the popularity of this style dwindled. In his later works, Gaulli too moved in this direction. Thus, in contrast to the grandeur of his composition at Il Gesù, we see Gaulli gradually adopting less intense colours, and more delicate compositions after 1685—all hallmarks of the Rococo.

Gaulli accumulated a large number of pupils, among them Ludovico Mazzanti, Giovanni Odazzi,[8] and Giovanni Battista Brughi (died 1730 in Rome).[9] He was described as easy to mount a rage; but ready to recover, where reason was satisfied... generous, liberal of mind, and charitable, specially towards the poor.[10]

Works

[edit]- Worship of the Holy Name of Jesus (1674–1679), Church of the Gesù, Rome

- Adoration of the Name of Jesus (1674–1679), Church of the Gesù, Rome

- Triumph in the Name of Jesus (1674–1679), Church of the Gesù, Rome

- Four Cardinal Virtues, Sant' Agnese, Rome

- Self-portrait, Uffizi, Florence

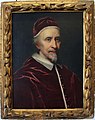

- Portraits of seven consecutive popes:

Gallery

[edit]-

Portrait of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1665

-

Cardinal Leopoldo de' Medici, Uffizi, Florence, c. 1667

-

Pietà, 1667

-

Blessed Ludovica Albertoni Distributing Alms, 1670

-

Bacchus and Ariadne, c. 1675

-

Portrait of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, c. 1675

-

Apotheosis of Saint Ignatius, Church of the Gesù, 1685

-

The Ascension of Our Lady

-

Clement IX

-

Nave of Church of the Gesù (1678-1679)

-

Worship of the Holy Name of Jesus with Bernini, Church of the Gesù

-

Triumph of Franciscan Order, Santi Apostoli, Rome

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ R. Soprani , p. 75.

- ^ Dizionario geografico-storico-statistico-commerciale degli stati del Re di Sardegna, by Goffredo Casalis, page 724.

- ^ F. Haskell p. 80.

- ^ F. Haskell p. 83.

- ^ "the eye is led stepwise from the dark to the light areas, the unfathomable abyss of heaven, where the Name of Christ appears" Wittkower R., p 174

- ^ See bozzetto in Galleria Borghese for a clearer map Archived 10 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ R. Wittkower, p. 332.

- ^ Palazzo Chigi Ariccia, Pinacoteca Archived 3 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Casalis, page 724.

- ^ R. Soprani

- Bibliography

- Gombrich, E.H. The Story of Art.

- Haskell, Francis (1980). Patrons and Painters: Art and Society in Baroque Italy. Yale University Press. pp. 80–85.

- Soprani, Raffaello (1769). Carlo Giuseppe Ratti (ed.). Delle vite de' pittori, scultori, ed architetti genovesi; Tomo secundo scritto da Carlo Giuseppe Ratti. Stamperia Casamara in Genoa, Oxford University copy on Feb 2, 2007. pp. 74–90.

Genovesi Raffaello Soprani.

- Wittkower, Rudolf (1980). Pelican History of Art (ed.). Art and Architecture Italy, 1600-1750. Penguin Books.

External links

[edit]