Australian tonalism

Australian tonalism was an art movement that emerged in Melbourne during the 1910s. Known at the time as tonal realism or Meldrumism, the movement was founded by artist and art teacher Max Meldrum, who developed a unique theory of painting, the "Scientific Order of Impressions". He argued that painting was a pure science of optical analysis, and believed that a painter should aim to create an exact illusion of spatial depth by carefully observing in nature tone and tonal relationships (shades of light and dark) and spontaneously recording them in the order that they had been received by the eye.[1]

Meldrum's followers—among the most notable being Clarice Beckett, Colin Colahan and William Frater—began staging group exhibitions at the Melbourne Athenaeum in 1919.[2] They favoured painting in adverse weather conditions, and often went out together in the morning or towards evening in search of fog and wintry wet surfaces, which provided increased spatial effects. Their subtle, "misty" depictions of Melbourne's beaches and parks, as well as its everyday, unadorned suburbia, show an interest in the interplay between softness and structure, nature and modernity.

The movement peaked during the interwar period, and its lingering influence can be seen in experimental works by other Australian artists, such as Lloyd Rees and Roland Wakelin. Although dismissed by many of their art world contemporaries, today the Australian tonalists are well-represented in Australia's major public art galleries, and are said to have initiated the first significant advance in Australian landscape painting since the Australian impressionists of the 1880s.[3] The minimum of means they used to distill the essence of their subjects has drawn comparisons to the haiku form of poetry, and the movement is regarded as a precursor to the late modernist style minimalism.[3][4][5]

History

[edit]

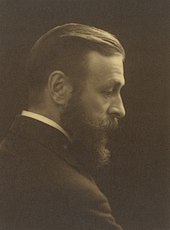

The main exponent of Australian tonalism was Melbourne artist Max Meldrum. In 1899, he won the National Gallery of Victoria Art School's Travelling Scholarship Award, and went to Paris to further his training. Dissatisfied with the academic teachings there, as well as the avant-garde, he instead taught himself and developed a unique theory of painting based on the importance of tonal values and objective optical analysis, what he termed the "Scientific Order of Impressions".[1] When applied, his photometric painting system resulted in simple representational works characterised by a "misty" or atmospheric quality.[6] Meldrum proposed:

All great art is a return to nature ... Art is a religion. The universe is its cathedral, and its creed is the humble and sublime one of all true artists and natural scientists whose faith is based upon demonstrable, visible or audible facts.

Meldrum returned to Melbourne in 1912, established an art school at Elizabeth Street and began publishing his theories of art, which created a storm in the Australian art world. His school of painting attracted equally passionate followers and critics, and artists who adopted Meldrum's methods became derisively known as "Meldrumites".[7][8][9] They rejected the then-popular Heidelberg School tradition with its emphasis on colour and narrative, and attacked various forms of modern art which Meldrum considered to be ego-based and technically inferior.[10] In 1918, incensed at Meldrum's defeat in the election for president of the Victorian Artists' Society, his students formed a breakaway group, the Twenty Melbourne Painters Society. The group often went on plein air painting trips around and outside Melbourne. When painting still life, the Australian tonalists set their easels at least six metres away from their subject, and painted with eyes half closed, or wore sunglasses, to aid their perception of different tones.

Meldrum's students staged their first group exhibition at the Athenaeum Gallery in 1919.[3] Presented as a unified whole, the two hundred and five works on show were uniformly displayed in narrow black frames, and in the catalogue, numbers, rather than titles, were assigned to each piece. The "radically humble" qualities of their art were overshadowed by controversy surrounding the show. Art historian Tracey Lock-Weir wrote:[4]

... it was bitterly received and divided the arts community. The sheer immediacy of its technique, its modest subject matter and the subtle appearance of the paintings fundamentally challenged well-established, nationalistic and elevated painting traditions that were more reliant on high craftsmanship and immediate visual impact.

Exhibitions

[edit]

- 1918 May, Victorian Artists' Society Autumn Exhibition, East Melbourne

- 1918 September, Victorian Artists' Society Spring Exhibition, East Melbourne

- 1919 September, A Meldrum Group, Athenaeum Gallery

- 1920 June, A Meldrum Group, Athenaeum Gallery[11]

- 1921 May, A Meldrum Group, Athenaeum Gallery

- 1933 March, Meldrum Gallery[12]

- 1934 October, A Meldrum Group, Athenaeum Gallery

List of artists

[edit]- Clarice Beckett

- Colin Colahan

- William Frater

- Polly Hurry

- Justus Jorgensen

- Percy Leason

- Max Meldrum

- Albert Newbury

- Jo Sweatman

Legacy

[edit]

Although Meldrum and his students rejected modern art, Australian tonalism is now regarded as a precursor to minimalism and related modernist styles of painting, due to its conceptual complexities and illusionary soft focus aesthetic.[4] In 2008, the Art Gallery of South Australia debuted Misty Moderns, the first major exhibition to cover Australian tonalism since the 1960s. Apart from Meldrum, Misty Moderns featured works by 17 of Meldrum's pupils, as well as artists who experimented with his tonalist system, including Lloyd Rees, Roland Wakelin, Roy de Maistre and Elioth Gruner.[13] The movement has been identified as "arguably the first important advance in Australian landscape painting since Australian Impressionism of the 1880s."[3]

See also

[edit]- Montsalvat, an art colony founded by Australian tonalist Justus Jorgensen

- Culture of Melbourne

- Visual arts of Australia

References

[edit]- ^ a b Meldrum, Max (2008). The science of appearances. Ames, Kenyon R. Frankston South, Vic.: Cinemascope Productions. ISBN 978-0-646-50288-5. OCLC 298654470.

- ^ Perry, Peter W. (1996). Max Meldrum & associates : their art, lives and influences. Castlemaine, Vic.: Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum. ISBN 0-9598066-7-9. OCLC 38415991.

- ^ a b c d Misty Moderns - Essay, National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ a b c Lock-Weir, Tracey. The sound of silence: Twentieth-century Australian tonalism, artaustralia.com. Retrieved on 5 December 2010.

- ^ Mclachlan, Scott (2017-04-28). "Presence and the Australian landscape". ART150: Celebrating 150 years of art. Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- ^ Misty Moderns: Australian Tonalists 1915-1950 Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Art Gallery of South Australia. Retrieved on 5 December 2010.

- ^ ""BLACKBALLING CANDIDATES"". The Herald. No. 13, 377. Victoria, Australia. 19 December 1918. p. 10. Retrieved 4 November 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "ARTISTS' TROUBLES REVIEWED". The Herald. No. 13, 381. Victoria, Australia. 24 December 1918. p. 8. Retrieved 4 November 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Haese, Richard; Haese, Richard, 1944-. Rebels and precursors (1982), Modern Australian art, Alpine Fine Arts Collection, ISBN 978-0-933516-50-2

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Kinnane, Garry. Colin Colahan: A Portrait. Melbourne University Publishing, 1996. ISBN 0-522-84710-2, p. 5

- ^ "PAINTING". Advocate. Vol. LII, no. 2750. Victoria, Australia. 10 June 1920. p. 21. Retrieved 28 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "ART". The Australasian. Vol. CXXXIV, no. 4, 397. Victoria, Australia. 15 April 1933. p. 17. Retrieved 28 July 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Edwards, David. Misty Moderns - Layer upon layer Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, The Blurb Magazine. Retrieved on 5 December 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Lock-Weir, Tracey. Misty Moderns: Australian Tonalists 1915-1950. Art Gallery of South Australia, 2008. ISBN 0-7308-3015-2.

- Perry, Peter. Max Meldrum & Associates: Their Art, Lives and Influences. Castlemaine Art Gallery, 1996. ISBN 0-9598066-7-9.