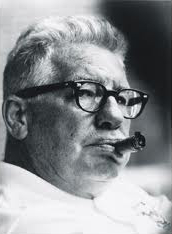

Art Rooney

Image of Rooney from "BELIEVE" posters | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born: | January 27, 1901 Coulterville, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died: | August 25, 1988 (aged 87) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Career information | |

| High school: | Duquesne University Prep |

| College: | Indiana Normal, Georgetown |

| Position: | Owner |

| Career history | |

| As an executive: | |

| |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Arthur Joseph Rooney Sr. (January 27, 1901 – August 25, 1988), often referred to as "the Chief", was an American professional football executive. He was the founding owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, an American football franchise in the National Football League (NFL), from 1933 until his death. Rooney is a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, was an Olympic qualifying boxer, and was part or whole owner in several track sport venues and Pittsburgh area pro teams. He was the first president of the Pittsburgh Steelers from 1933 to 1974, and the first chairman of the team from 1933 to 1988.

Family history

[edit]Rooney's great-grandparents, James and Mary Rooney, were Irish Catholics who emigrated from Newry in County Down, Ireland to Canada during the Great Famine in the 1840s. While living in Montreal, the Rooneys had a son, Arthur (who would become Art Rooney's grandfather). James and Mary later moved to Ebbw Vale, Wales, where the iron industry was flourishing, taking their son Arthur, then 21, with them. This Arthur Rooney married Catherine Regan (who was also Irish Catholic), in Wales, and they had a son, Dan. Two years after Dan Rooney was born, the family moved back to Canada and eventually ended up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1884. Along the way the family grew to include nine children of which Dan was the second.[1]

Dan Rooney remained in the Pittsburgh area, and eventually opened a saloon in the Youghiogheny Valley coal town of Coulter, Pennsylvania (or Coultersville). This is where Dan Rooney met and wed Margaret "Maggie" Murray, who was the daughter of a coal miner, and where the couple's first son, Arthur Joseph Rooney, was born. Dan and Maggie would eventually settle their family in Pittsburgh's North Side in 1913, where they bought a three-story building at the corner of Corey Street and General Robinson Street. Dan operated a cafe and saloon out of the first floor with the family living above. The building was located just a block from Exposition Park, which had been home to the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team until 1909.[1]

Rooney had a brother, Silas Rooney, who later entered the priesthood. Silas Rooney eventually became the athletic director for St. Bonaventure University in 1947 and invited the Steelers to play their training camp at the university in the 1950s.[2] Another brother, James P. Rooney, later was elected to the Pennsylvania General Assembly, winning easily in part because Art had renamed the team after James, who also played on the squad, as a promotional tactic.[3]

Education and athletics

[edit]

Rooney attended St. Peter's Catholic School in Pittsburgh, Duquesne University Prep School, then several semesters at Indiana Normal School before completing a final year at Temple University on an athletic scholarship.[4] He was awarded for his athleticism at Indiana (now the Indiana University of Pennsylvania) by being posthumously inducted into the IUP athletic Hall of Fame in 1997. He spent his time there participating on both the basketball and football teams while also playing centerfielder for the Crimson Hawks baseball team.[5]

After his high school graduation in 1919, he dedicated himself to sports. Initially, Rooney became an accomplished boxer, winning the AAU welterweight belt in 1918 and tried out for the 1920 Olympic Team,[6]

He played minor league baseball for both the Flint, Michigan "Vehicles" and the Wheeling, West Virginia "Stogies".[7] In 1925 he served as Wheeling's player-manager and led the Middle Atlantic League in games, hits, runs, stolen bases and finished second in batting average (his brother Dan Rooney, Wheeling's catcher that year, finished third).

Rooney also played the halfback position for the semi-pro Pittsburgh "Hope Harvey" and "Majestic Radio" clubs, the former of which he later took over and renamed the J.P. Rooneys before purchasing an NFL franchise for $2,500 in 1933 following the repeal of Pennsylvania's blue laws.[4] During this time, Rooney served as the team's general manager, head coach and owner. His team played games at the Exposition Park baseball field in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh, which would later be the home of Rooney's team the Pittsburgh Steelers.[8]

Pittsburgh Steelers

[edit]

Rooney's affiliation with the National Football League (NFL) began in 1933 when he paid a $2,500 franchise fee to found a club based in the city of Pittsburgh. He named his new team the "Pirates", after the city's baseball team, of which Rooney was a fan since childhood.

Since the league's inception in 1920, the NFL had wanted a team in Pittsburgh due to the city's already-long history with football as well as the popularity of the Pittsburgh Panthers football team, an NCAA national championship contender during this period. The league was finally able to take advantage of Pennsylvania relaxing their blue laws that prior to 1933 prohibited sporting events from taking place on Sundays, when most NFL games take place.

In 1936, Rooney won a parlay at Saratoga Race Course, which netted him about $160,000. He placed the bet based on a tip from New York Giants owner Tim Mara, a bookmaker.[9] He used the winnings to hire a coach, Joe Bach, give contracts to his players and almost win a championship. The winnings funded the team until 1941 when he sold the franchise to NY playboy Alex Thompson. Thompson wanted to move the franchise to Boston so he could be within a five-hour train ride of his club. At the same time, the Philadelphia Eagles ran into financial problems. Rooney used the funds from the sale of franchise to get a 70% interest in the Eagles, the other 30% held by Rooney friend and future NFL commissioner, Bert Bell. Bell and Rooney agreed to trade places with Thompson. Bell took the role of President of the Steelers that he relinquished to Rooney in 1946 when Bell became Commissioner. Rooney got his good friend and his sister's father in law, Barney McGinley, to buy Bell's shares. Barney's son Jack, Art's brother in law, retained the McGinley interest that passed to his heirs when he died in 2006.[10]

The Rooneys are the finest people, the people I most respect in American sports ownership. I've always felt that way. And there's no reason to change. They are people of integrity and character. The way they put the Steelers together, to hire a man like Chuck Noll, to emphasize the team concept. I have a whole transcendental feeling for the Steelers and the Rooneys and Pittsburgh.

Rooney sent shock waves through the NFL by signing Byron "Whizzer" White to a record-breaking $15,000 contract in 1938. This move, however, did not bring the Pirates a winning season, and White left the team for the Detroit Lions the following year. The club did not have a season above .500 until 1942, the year after they were renamed the Pittsburgh Steelers.

During World War II, the Steelers had some financial difficulties and were merged with the Philadelphia Eagles in 1943 and the Chicago Cardinals in 1944.

After the war, Rooney became team president. He longed to bring an NFL title to Pittsburgh but was never able to beat the powerhouse teams, like the Cleveland Browns and Green Bay Packers. The Steelers also struggled with playing in a city and era where baseball was king and were treated as something of a joke compared to the Pirates. The team also made some questionable personnel calls at the time such as cutting a then-unknown Johnny Unitas in training camp (Unitas would go on to a Hall of Fame career with the Baltimore Colts) and trading their first round pick in the 1965 draft to the Chicago Bears (who would draft Dick Butkus with the pick), among others.

Nevertheless, Rooney was popular with owners as a mediator, which would carry over to his son Dan Rooney. He was the only owner to vote against moving the rights of the New York Yanks to Dallas, Texas after the 1951 season due to concerns of racism in the South at the time.[12] (Ultimately, the Dallas Texans failed after one year, and the rights were moved to Baltimore, where the team became the Baltimore Colts. The team now plays in Indianapolis.) In 1963, along with Bears owner George Halas, Rooney was one of two owners to vote for the 1925 NFL Championship to be reinstated to the long-defunct Pottsville Maroons.

Pittsburgh Penguins

[edit]As a pillar of the community in many aspects, Rooney was asked to lend his considerable influence in the city's bid to reclaim an NHL franchise during the league's expansion in 1967. Although Pittsburgh enjoyed championship hockey with the professional but "minor league" Pittsburgh Hornets since its NHL franchise (the Pirates hockey team) disbanded in 1930 from the effects of the Great Depression, many city leaders were pushing for the region to become more "major league" suggesting that Mr. Rooney use his influence in the sports industry to have the league award Pittsburgh a franchise. Rooney proved his worth and from 1967 until the early 1970s was a part owner of the Pittsburgh Penguins.[13][14]

Homestead Grays

[edit]In a 1981 interview by the Pittsburgh Press Rooney related that "from time to time he had helped financially support the Negro league team, the Homestead Grays, and . . . was a better baseball fan than football fan."[15]

Track sports

[edit]Rooney also acquired the Yonkers Raceway in 1972, the Palm Beach Kennel Club, Green Mountain Kennel Club in Vermont, Shamrock Stables in Maryland and owned the Liberty Bell Park Racetrack outside Philadelphia.[16]

Later life

[edit]Following the AFL–NFL merger in 1970, the Steelers agreed to leave the NFL Eastern Conference and joined the AFC Central Division.

Everyone knew Mr. Rooney was our number one citizen...he did more for this city than R.K. Mellon did for the business community and David Lawrence and any of the mayors who followed him, including Richard Caliguiri, did politically.

Through expert scouting, the Steelers became a power. In 1972, they began a remarkable 8–year run of playoff appearances, and 13 straight years of winning seasons, including three additional playoff berths. In Rooney's 41st season as owner, the club won the Super Bowl. During Rooney's lifetime the team also had Super Bowl victories following the 1975, 1978 and 1979 seasons. They also won the Super Bowl in the 2005 and 2008 seasons, making the Steelers the first-team following the AFL–NFL merger to win six Super Bowls.

I'll never forget the way he introduced me, 'This is Ralph Giampaolo, a member of our organization.' Not a member of our ground crew. Not some rinky-dink bum. But a member of 'our organization'. As far as [Curt] Gowdy knew, I was vice president of the team. Mr. Rooney made me feel 10 feet tall.

Following the Steelers' victory in Super Bowl IX, Rooney stepped down from day-to-day management of the team, but remained the ultimate source of authority until his death. Dan, his son, took over as team president. Rooney died from complications of a stroke on August 25, 1988. An August 1987 Pittsburgh Press story stated that Rooney never missed a Hall of Fame induction ceremony in all 25 years, and that he was asked to present his third inductee, John Henry Johnson, that month.[18] In memory of "The Chief," Steelers wore a patch on the left shoulder of their uniforms with Rooney's initials AJR for the entire season. The team ended up finishing 5-11, their worst record since a 1–13 showing in 1969. He is buried at the North Side Catholic Cemetery in Pittsburgh.[19]

Legacy

[edit]

In 1964, he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Duquesne University named their football field in his honor in 1993. In 1999 Rooney ranked 81st on the Sporting News' "100 Most Powerful Sports Figures of the 20th Century" list. A statue of his likeness graces the entrance to the home of the Pittsburgh Steelers, Heinz Field. The street that runs adjacent to Heinz Field on Pittsburgh's North Side is named "Art Rooney Avenue" in his honor.[20][21] In 2000, he was inducted as a "pioneer" into the American Football Association's Semi-Pro Football Hall of Fame.[22]

During Rooney's life, the Steelers would often use a late-round draft pick on a player from a local college like Pitt, West Virginia or Penn State. Though these players rarely made the team, this practice was intended to appeal to local fans and players.

Art Rooney is the finest person I've ever known.

[The] most popular sports figure in history.

Art Rooney is the subject of, and the only character in, the one-man play The Chief, written by Gene Collier and Rob Zellers.

My father always used to tell us boys, "Treat everybody the way you'd like to be treated. Give them the benefit of the doubt. But never let anyone mistake kindness for weakness." He took the Golden Rule and put a little bit of the North Side in it.

Arthur J. Rooney was married to Kathleen Rooney née McNulty (1904–1982) for 51 years, until her 1982 death. Kathleen was the mother of Art's five sons, who are Dan Rooney, the chairman of the board of directors of the Pittsburgh Steelers and a former United States Ambassador to Ireland, Art Rooney Jr., Timothy Rooney, Patrick Rooney, and John Rooney (all also directors of the Pittsburgh Steelers). She is also the grandmother of the couple's 32 grandchildren, including current Steelers president Art Rooney II and U.S. Representative Thomas J. Rooney (R, FL-16). The couple also has about 75 great-grandchildren, including actress sisters Kate Mara and Rooney Mara.[26][27][28][29]

References

[edit]General

- Klavon, Jacqueline E. "Rooney, Arthur Joseph (The Chief) bio". Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

Specific

- ^ a b Rooney, Arthur J. (Jr.); McHugh, Roy (2008). Ruanaidh:The Story of Art Rooney and his clan. artrooneyjr.com. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-0-9814760-3-2.

- ^ "Destroy Evidence Of Bona Grid Climb". Binghamton Press. June 17, 1959. p. 50 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Willis, Chris (2010). The Man Who Built the National Football League, Joe F. Carr. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7670-5.

- ^ a b Johnson, Vince (September 30, 2007). "From the PG Archives: Rooney Unique in Pro Football Hall of Fame". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ "Art Rooney (1997)". Indiana University of Pennsylvania Athletics. January 6, 2025. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ "Art Rooney Signed AAU Welterweight Champion Reproduction Card". www.americanmemorabilia.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ "Art Rooney Minor Leagues Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Dedman, Gordon (April 11, 1948). "Early Steelers history". SteelersUK. Retrieved January 18, 2025.

- ^ The Washington Post (subscription required)

- ^ Tucker, Murray (October 2007). Screamer: The Forgotten Voice of the Pittsburgh Steelers. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0595471256.

- ^ "The Pittsburgh Press - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ 75 Seasons: The Complete Story of the National Football League, pg. 103

- ^ "1967-68 NHL Expansion". Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ "Lawrence Journal-World - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Pittsburgh Press - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Tuma, Gary (October 14, 2007). "From the PG Archives: Steelers' Art Rooney in retrospect". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ a b "Art Rooney". www.pittsburghsteelers.co.uk. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Pittsburgh Press - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Chief". old.post-gazette.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ "Map of Art Rooney Avenue". Google Maps. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ Barnes, Tom (August 1, 2001). "There has been development near the new stadiums, but no one is sure what will happen between them". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "2010 Hall of Fame listing" (PDF). americanfootballassn.com/ American Football Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 23, 2011. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "Art Rooney Never Changed". The New York Times. August 26, 1988.

- ^ "Inquirer.com: Philadelphia local news, sports, jobs, cars, homes". inquirer.com. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Mendelson, Abby (1996). The Pittsburgh Steelers: The Official Team History. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-87833-957-0.

- ^ The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, Vol. 2 (1986–1990), pp. 741-742, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1999

- ^ "The Rooneys: A fight for future generations". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 13, 2008. Retrieved October 15, 2024.

- ^ "1988 NY Times obituary for Art Rooney". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ "'The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo' is … Rooney Mara". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- O'Brien, Jim (2001). The Chief: Art Rooney and his Pittsburgh Steelers. Pittsburgh: James P. O'Brien – Publishing. ISBN 1-886348-06-5.

External links

[edit]- 1901 births

- 1988 deaths

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- American people of Irish descent

- American Roman Catholics

- Duquesne Dukes football players

- Georgetown University alumni

- National Football League team presidents

- National Hockey League executives

- National Hockey League owners

- People from South Versailles Township, Pennsylvania

- Pittsburgh Lyceum (football) players

- Pittsburgh Penguins owners

- Pittsburgh Steelers executives

- Pittsburgh Steelers owners

- Players of American football from Pennsylvania

- Pro Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Rooney family

- Steagles players and personnel

- Wheeling Stogies players