Art Gallery of New South Wales

Facade of the Naala Nura building and entrance designed by Walter Vernon | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | 1874 |

|---|---|

| Location | Art Gallery Road, The Domain, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°52′07″S 151°13′02″E / 33.868686°S 151.217144°E |

| Type | Fine arts, visual arts, Asian arts |

| Visitors | 1,926,679 (2022–23)[1] |

| Director | Dr Michael Brand |

| Public transit access |

|

| Website | artgallery |

The Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), founded as the New South Wales Academy of Art in 1872 and known as the National Art Gallery of New South Wales between 1883 and 1958, is located in The Domain, Sydney, Australia. It is the most important public gallery in Sydney and one of the largest in Australia.

The gallery's first public exhibition opened in 1874. Admission is free to the general exhibition space, which displays Australian art (including Indigenous Australian art), European and Asian art. A dedicated Asian Gallery was opened in 2003.

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]

On 24 April 1871, a public meeting was convened in Sydney to establish an Academy of Art "for the purpose of promoting the fine arts through lectures, art classes and regular exhibitions." Eliezer Levi Montefiore (brother of Jacob Levi Montefiore and nephew of Jacob and Joseph Barrow Montefiore) co-founded the New South Wales Academy of Art (also referred to as simply the Academy of Art)[3][4][5] in 1872. From 1872 until 1879, the academy's main activity was the organisation of annual art exhibitions. The first exhibition of colonial art, under the auspices of the academy, was held at the Chamber of Commerce, Sydney Exchange in 1874.

In 1874, the New South Wales Parliament voted funds towards a new Art Gallery of New South Wales, with a board of trustees to administer the funds, one of whom was Montefiore.[6]

In 1875, Apsley Falls by Conrad Martens, commissioned by the trustees and purchased for £50 out of the first government grant of £500, became the first work on paper by an Australian artist to be acquired by the gallery.[7]

The gallery's collection was first housed at Clark's Assembly Hall in Elizabeth Street where it was open to the public on Friday and Saturday afternoons. The collection was relocated in 1879 to a wooden annexe to the Garden Palace built for the Sydney International Exhibition in the Domain and was officially opened as the Art Gallery of New South Wales on 22 September 1880.[8][6] In 1882 Montefiore and his fellow trustees opened the art gallery on Sunday afternoons from 2 pm to 5 pm. Montefiore believed:[8]

the public should be afforded every facility to avail themselves of the educational and civilising influence engendered by an exhibition of works of art, bought, moreover, at the public expense.

Montefiore was president of the board of trustees from 1889 to 1891, and became the director of the gallery in 1892, a position he retained until his death in 1894.[6]

The destruction of the Garden Palace by fire in 1882 placed pressure on the government to provide a permanent home for the national collection.[7] In 1883 private architect John Horbury Hunt was engaged by the trustees to submit designs.[9] The same year there was a change of name to the National Art Gallery of New South Wales.[5] The gallery was incorporated by The Library and Art Gallery Act 1899.[9][10]

In 1895, the newly appointed government architect, Walter Liberty Vernon,[11] was given the assignment to design the new permanent gallery and two picture galleries were opened in 1897 and a further two in 1899. A watercolour gallery was added in 1901 and in 1902 the Grand Oval Lobby was completed.[10] The 32 names below the entablature were chosen by the gallery's board of trustees president, Frederick Eccleston Du Faur. The names were of were painters, sculptors, and architects with no connection to any works in the gallery at the time. Several calls to replace these names with notable Australian artists failed because the trustees could not decide on alternatives.[12]

20th century

[edit]Over 300,000 people came to the gallery during March and April 1906 to see Holman Hunt's painting The Light of the World. In 1921, the inaugural Archibald Prize was awarded to William McInnes for his portrait of architect Desbrowe Annear. The equestrian statues The Offerings of Peace and The Offerings of War by Gilbert Bayes were installed in front of the main facade in 1926.[14] James Stuart MacDonald was appointed director and secretary in 1929. In 1936 the inaugural Sulman Prize was awarded to Henry Hanke for La Gitana. Will Ashton was appointed director and secretary in 1937.[7]

The first woman to win the Archibald Prize was Nora Heysen in 1938 with her portrait Mme Elink Schuurman, the wife of the Consul General for the Netherlands. The same year electric light was temporarily installed at the gallery to remain open at night for the first time. In 1943 William Dobell won the Archibald Prize for Joshua Smith, causing considerable controversy. Hal Missingham was appointed director and secretary in 1945.

On 1 July 1958 the Art Gallery of New South Wales Act was amended and the gallery's name reverted to the "Art Gallery of New South Wales". (Dropping the first word 'National'.)[15][5]

In 1969 construction began on the Captain Cook wing to celebrate the bicentenary of Cook's landing in Botany Bay. The new wing opened in May 1972, following the retirement of Missingham and the appointment of Peter Phillip Laverty as director in 1971.[7]

The first of the modern blockbusters to be held at the gallery was Modern Masters: Monet to Matisse in 1975. It attracted 180,000 people over 29 days. The 1976 the Biennale of Sydney was held at the gallery for the first time. The Sydney Opera House had been the location for the inaugural Biennale in 1973. 1977 saw an exhibition "A selection of recent archaeological finds of the People's Republic of China."[16][17] Edmund Capon was appointed director in 1978 and in 1980 The Art Gallery of New South Wales Act (1980) established the "Art Gallery of New South Wales Trust".[18] It reduced the number of trustees to nine and stipulated that "at least two" members "shall be knowledgeable and experienced in the visual arts."[7]

With the support of Premier Neville Wran a major extension of the gallery became a Bicennential project. Opened just in time in December 1988, the extensions doubled the floor space of the gallery. In 1993 Kevin Connor won the inaugural Dobell Prize for Drawing for Pyrmont and city. In 1994, the Yiribana Gallery, dedicated to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art, was opened.[7]

21st century

[edit]

- 2000–2009

In 2001, the New South Wales Art Gallery announced that nine of the gallery's 40,000 artworks could have been among the many paintings stolen by the Nazis and that it was undertaking provenance research.[19][20]

In 2003 an Art After Hours program was initiated with the gallery opening hours extended every Wednesday. The inaugural Australian Photographic Portrait Prize was won by Greg Weight. The Art Gallery Society of New South Wales celebrated its 50th anniversary in the same year and the Rudy Komon Gallery exhibition space was opened, followed by the new Asian gallery.[7]

A 2004 exhibition of Man Ray's work set an attendance record for photography exhibitions, with over 52,000 visitors. The same year a legal challenge was mounted against the award of the Archibald Prize to Craig Ruddy for his David Gulpilil, two worlds; and the Anne Landa Award was established, Australia's first award for moving image and new media. The Nelson Meers Foundation Nolan Room was opened, also in 2004, with a display of five major Sidney Nolan paintings gifted to the gallery by the foundation over the past five years.[7]

myVirtualGallery was launched on the gallery's website in 2005 and the former boardroom was reopened for display of paintings, sculptures and works on paper by Australian artists.[7]

In 2005 Justice John Hamilton of the Supreme Court of New South Wales ruled in favour of the gallery over the disputed 2004 award of the Archibald Prize to Craig Ruddy.[21] The same year, James Gleeson and his partner Frank O'Keefe pledged A$16 million through the Gleeson O'Keefe Foundation to acquire works for the gallery's collection.[7]

On 10 June 2007, a 17th-century work by Frans van Mieris, entitled A Cavalier (Self-Portrait), was stolen from the gallery.[22][23] The painting had been donated by John Fairfax and was valued at over A$1 million.[24] The theft raised questions about need for increased security at the gallery.[25] In the same year the Belgiorno-Nettis family donated A$4 million over four years to the gallery to support contemporary art.[7]

In 2008 the gallery purchased Paul Cézanne's painting Bords de la Marne c. 1888 for A$16.2 million – the highest amount paid by the gallery for a work of art. In the same year the NSW Government announced a grant of A$25.7 million to construct an offsite storage facility and a gift from the John Kaldor Family Collection to the gallery was announced. Valued at over A$35 million, it comprised some 260 works representing the history of international contemporary art.[7] The refurbishment of the 19th-century Grand Courts was celebrated in the gallery's inaugural 'Open Weekend' in 2009.[7]

- 2010–present

A new contemporary gallery was created in 2010 by removing storage racks from the lowest level of the Captain Cook wing, and artworks were relocated to a new purpose-built off-site collection storage facility. The same year, the award of the Wynne Prize to Sam Leach for Proposal for landscaped cosmos caused controversy due to the painting's resemblance to a 17th-century Dutch landscape; and the gallery announced Mollie Gowing's bequest of 142 artworks plus A$5 million to establish two endowment funds for acquisitions: one for Indigenous art and a larger one for general acquisitions.[7]

Also in 2010 the Balnaves Foundation Australian Sculpture Archive was established, funded by the Balnaves Foundation, "to acquire the archives of major Australian sculptors and to extend research in three-dimensional practice".[26]

The 2011 exhibition The First Emperor: China's Entombed Warriors attracted more than 305,000 people and in the same year new contemporary galleries were opened, including the John Kaldor Family Gallery, plus a dedicated photography gallery and a refurbished works-on-paper study room.[7] In August 2011 Edmund Capon announced his retirement after 33 years as director.[27]

Michael Brand assumed the role of director in mid-2012. Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris attracted almost 365,000 visitors – the largest number ever to an exhibition at the gallery, also in 2012 and Michael Zavros won the inaugural Bulgari Art Award with The New Round Room. In the same year Kenneth Reed announced his intention to bequeath his entire private collection of 200 pieces of rare and valuable 18th-century European porcelain valued at A$5.4 million.[7]

In 2013 the gallery unveiled a strategic vision and masterplan, under the working title Sydney Modern: a proposal for major expansion and renewed focus on serving a global audience. The stated aim was to complete the project by 2021, the 150th anniversary of the gallery's founding in 1871.[7] In the same year, the gallery received A$10.8 million from the NSW Government to finance the planning stages of Sydney Modern, which would see the construction of a new building and double the size of the institution. The money was used over the next two years for feasibility and engineering studies related to the use of land next to the gallery's existing 19th-century home, and to launch an international architectural competition.[28]

The International design competition for the Sydney Modern Project resulted in five architectural firms being invited from an original list of twelve to submit their final concept designs in April 2015.[29] A mix of private and NSW Government funds will pay for the A$450 million project,[30][31] The firm of McGregor Coxall was chosen to redesign the gardens.[32] The project has attracted controversy for its expense and encroachment into the public land of the Domain and the Royal Botanic Garden and its dependence on "much greater commercialisation".[33][34]

In 2023, the gallery launched Volume, an annual festival combining experimental live music and performance events. The inaugural festival, held in September to October 2023, featured music events from artists including Solange, with headline events held in The Tank, a repurposed concrete oil tank located under the Sydney Modern project building.[35][36]

Buildings

[edit]The Vernon building

[edit]

In 1883 John Horbury Hunt, an architect in private practice, was engaged by the gallery's trustees to design a permanent gallery. Though Hunt submitted four detailed designs in various styles between 1884 and 1895, his work came to nothing apart from a temporary building in the Domain. With raw brick walls and a saw-tooth roof, it was denounced in the press as the "Art Barn".[37]

Newly appointed government architect, Walter Liberty Vernon, secured the prestigious commission over John Horbury Hunt in 1895. Vernon believed that the Gothic style admitted greater individuality and richness 'not obtainable in the colder and unbending lines of Pagan Classic.' The trustees were not convinced and demanded a classical temple to art, not unlike William Henry Playfair's Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, opened in 1859.[37]

Vernon's building, housing eight daylight lit courts, was built in four stages. The first stage was commenced in 1896 and opened in May 1897. By 1901 the entire southern half of the building was finished. A newspaper article at the time noted:

Only one wing of the building, about one fourth of the whole structure, is at present completed, and gives rich promise of future beauty. The style is early Greek. The façade is built of thracyte and freestone. The interior is divided into four halls, each 100 feet by 30 feet, communicating with each other by pillared archways. The lighting is almost perfect, designs for the roof having been furnished by London correspondents after careful study of all the latest improvements in European galleries. The walls are coloured a chill neutral green shade, which makes an excellent background.[37]

Vernon proposed that his oval lobby lead into an equally imposing Central Court. His plans were not accepted. Until 1969 his lobby led, by a short descent from the entrance level, to the three 'temporary' northern galleries designed by Hunt.[37]

In 1909 the front of the gallery was finished and after this date nothing more was built of Vernon's designs. In the 1930s plans were suggested for the completion of this part of the gallery but the Great Depression and other financial constraints lead to their abandonment.[37]

Captain Cook Wing

[edit]In 1968 the New South Wales Government decided the completion of the gallery would be a major part of the Captain Cook Bicentenary celebrations. This extension, which was opened to the public on 2 May 1972, and the 1988 Bicentennial extensions, were both entrusted to the New South Wales Government Architect, with Andrew Andersons the project architect.[37]

The architecture of the Captain Cook Wing did not attempt to clone the classical style of Vernon's design. Andersons' design philosophy was akin to that espoused by Robert Venturi in his book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, as Andersons explains:

He [Venturi] argued the case for richer and more complex forms of architectural expression – for 'the juxtaposition of old and new' for dramatic visual impact, rather than striving for unity and consistency in architecture that conventional precepts then dictated.[38]

In the Captain Cook Wing, the architect Andersons divided new from old with a wide strip of skylights in the main entry court. While in the old courts there was parquetry flooring, travertine flooring was employed in the new galleries for both permanent and temporary exhibitions. The modern need for flexibility in display layout was answered by the use of track lighting and precast ceiling panels designed to support a system of demountable walls. While the new galleries were painted off white, senior curator, Daniel Thomas, advocated a rich Victorian colour scheme to display the gallery's 19th-century paintings in Vernon's grand courts.[38]

In 1975 the Captain Cook Wing was awarded the Sir John Sulman Medal for Public Architecture by the NSW Chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects. In 2007 the building was acknowledged with the New South Wales Enduring Architecture Award.[39]

Bicentennial extension

[edit]Sixteen years later the 1988 Bicentennial extension was built on the Domain parkland sloping steeply to the east. Within the constraints of two large Moreton Bay fig trees, and with a substantial part of the accommodation below ground level, the extension doubled the size of the gallery. Space for permanent collections and temporary exhibitions was expanded, a new Asian gallery, the Domain Theatre, a café overlooking Woolloomooloo Bay, and a rooftop sculpture garden were added. Escalators connected four exhibition levels with the entry/orientation space. Four contemporary art 'rooms' were top lit by pyramid skylights.[37]

Asian Art Gallery expansion

[edit]A new space for Asian art was built to add to the existing Asian art gallery immediately below. Backlit translucent external cladding glows at night and has been dubbed the 'light box'. This addition was coupled with other alterations: a new temporary exhibition space on the top level, new conservation studios, an outward expansion of the café overlooking Woolloomooloo Bay, a new restaurant with dedicated function area, a theatrette and relocation of the gallery shop. The project was designed was by Sydney architect Richard Johnson and was opened on 25 October 2003.[40] The space involves art from all corners of Asia, including Buddhist and Hindu arts, Indian sculptures, Southern Asian textiles, Chinese ceramics and paintings, Japanese works and more.

The aesthetics of the extension were described as "cantilevered on top of the original Asian galleries, the pavilion glows softly like a paper lantern when lit at night" and as "a floating white glass and steel cube pivoted with modern stainless steel lotus flowers".[41] The extension added 720 square metres (7,800 sq ft) to the New South Wales Art Gallery, with the new space to house temporary and permanent exhibitions. In 2004 Johnson Pilton Walker won two awards for their design of the Asian Galleries extension, including an RAIA National Commendation in the Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Architecture category; and a RAIA NSW Chapter Architecture Award for Public and Commercial Buildings.[42][43] Over A$16 million was granted from the NSW Government for this major building project – inclusive also of the Rudy Komon Gallery, new conservation studios, café, restaurant and function area, and a refurbishment of the administration area.[44]

Sydney Modern project

[edit]

A competition to expand the gallery as part of the 'Sydney Modern' project was won in 2015 by Tokyo architects Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa of SANAA.[45] The chosen design, which proposed a large extension to the north, was criticised on architectural as well as public interest grounds. Former architect Andersons described it as intrusive, 'colliding' with Vernon's sandstone façade and relegating his portico to a ceremonial entrance.[46] Former Prime Minister Paul Keating criticised plans to significantly develop the outdoor spaces near the gallery for use as private venues as "about money, not art".[47] The Foundation and Friends of the neighbouring Royal Botanic Garden objected to the proposed loss of green space and parkland in the adjacent Domain, requested a review and negotiated with the gallery about sight lines, transport, logistics and alignment of built structures.[48][49]

The extension opened on 2 December 2022, almost doubling the gallery's exhibition space, to 16,000 square metres in total.[50][51] The project cost $344 million in total, of which $244 million came from the NSW Government.[50] The new spaces displayed a range of contemporary and installation works, with a particular focus on First Nations artwork.[50] The new gallery did not adopt the 'Sydney Modern' project title as the permanent name of the new building, and at the time of its opening in 2022 a decision had not been made on what the new gallery would be called.[50] The new, cascading exhibition spaces featured large windows with views onto Sydney Harbour, and converted a large underground oil bunker into a columned gallery spaced called 'The Tank'.[51] In April 2024 it was announced the Sydney Modern (north building) would be called an Aboriginal name Naala Badu, meaning 'seeing waters' in the Sydney language. The south building is to be named Naala Nura, meaning 'seeing country'.[52]

Collections

[edit]In 1871 the collection started with the acquisition by The Art Society of some large works from Europe such as Ford Madox Brown's Chaucer at the Court of Edward III. Later they bought work from Australian artists such as Streeton's 1891 Fire's On, Roberts' 1894 The Golden Fleece and McCubbin's 1896 On the Wallaby Track.

In 2014 the collection is categorised into:

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art

[edit]AGNSW did not have any Indigenous Australian art until the middle of the twentieth century. In 1948, it acquired a donation of bark and paper paintings from the 1948 American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. Deputy director Tony Tuckson then started expanding the collection. In 1959 a series of 17 Pukamani grave posts from the Tiwi Islands were installed in the forecourt, which started to change public perception of Aboriginal art, as contemporary art. In October 1973 the Primitive Art Gallery opened, with Tuckson as curator. The first Indigenous curators were appointed in 1984.[53]

Hetti Perkins worked at AGNSW from 1989, as the senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art at the gallery from around 1998 until 2011, when she resigned. She was responsible for some major exhibitions and initiatives during her time there.[54]

Perkins worked on the establishment of the Yiribana Gallery, dedicated to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art, which opened in 1994.[55][53]

The AGNSW collection represents Indigenous artists from communities across Australia. The earliest work in the collection, by Tommy McRae, dates from the late 19th century. Included in the collection are desert paintings created by small family groups living on remote Western Desert outstation, bark paintings of the saltwater people of coastal communities, and the new media expressions of "blak city culture" by contemporary artists.[7]

Asian art

[edit]The first works to enter the collection in 1879 were a large group of ceramics and bronzes – a gift from the Government of Japan following the Sydney International Exhibition that year. The Asian collections after grown from that beginning to be wide-ranging, embracing the countries and cultures of South, Southeast and East Asia.[7]

Australian art

[edit]The collection dates from the early 1800s. 19th-century Australian artists represented include: John Glover, Arthur Streeton, Eugene von Guerard, John Russell, Tom Roberts, David Davies, Charles Conder, William Piguenit, E. Phillips Fox (including Nasturtiums), Frederick McCubbin, Sydney Long and George W. Lambert.[7]

20th-century Australian artists represented include: Arthur Boyd, Rupert Bunny, Grace Cossington Smith, H. H. Calvert, William Dobell, Russell Drysdale, James Gleeson, Sidney Nolan, John Olsen, Margaret Preston, Hugh Ramsay, Lloyd Rees, Imants Tillers, J. W. Tristram, Roland Wakelin, Brett Whiteley, Fred Williams and Blamire Young.[7]

Forty four works held at the gallery were included in the 1973 edition of 100 Masterpieces of Australian Painting.[56]

Selected works

[edit]-

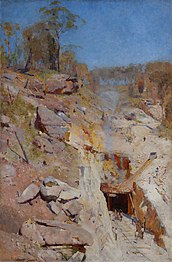

John Glover, Natives on the Ouse River, Van Diemen's Land, 1838

-

Arthur Streeton, Fire's on, 1891

-

Charles Conder, The hot sands, Mustapha, Algiers, 1891

-

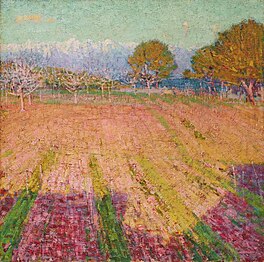

John Russell, In the Afternoon, 1891

-

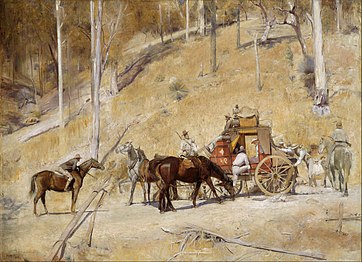

Tom Roberts, Bailed Up, 1895

-

Hugh Ramsay, The Sisters, 1904

-

Rupert Bunny, Summer time, 1907

-

E. Phillips Fox, The Ferry, 1910

-

Elioth Gruner, Spring Frost, 1919

-

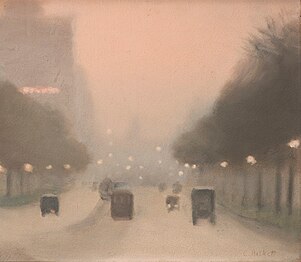

Clarice Beckett, Evening, St Kilda Road, 1930

Contemporary art

[edit]The contemporary collection is international, encompassing Asian and Western as well as Australian art in all media. With the gift of the John Kaldor Family Collection, the gallery now holds arguably Australia's most comprehensive representation of contemporary art from the 1960s to the present day. Internationally, the focus is on the influence of conceptual art, nouveau realisme, minimalism and arte povera. The Australian contemporary art collection focuses on abstract painting, expressionism, screen culture and pop art.[7]

Pacific art

[edit]The collection of art from the Pacific region began in 1962 at the instigation of our then deputy director, Tony Tuckson. Between 1968 and 1977, the gallery acquired over 500 works from the Moriarty Collection, one of the largest and most important private collections of New Guinea Highlands art in the world.[7]

Photography

[edit]

The photography collection has major holdings of a wide variety of artists including Tracey Moffatt, Bill Henson, Fiona Hall, Micky Allan, Mark Johnson, Max Pam and Lewis Morley. As well as contemporary photography, Australian pictorialism, modernism and postwar photo documentary is represented by The Sydney Camera Circle, Max Dupain and David Moore. The evolution of 19th-century Australian photography is represented with emphasis on the work of Charles Bayliss and Kerry & Co. International photographs include English pictorialism and the European avant garde (Bauhaus, constructivism and surrealism). Photo-documentary in 20th-century America is reflected through the work of Lewis Hine and Dorothea Lange among others. Contemporary Asian practices are represented by artists such as Yasumasa Morimura and Miwa Yanagi. Styles range from the formal aesthetics of early photography to the informal snapshots of Weegee to the high fashion of Helmut Newton and Bettina Rheims.[7]

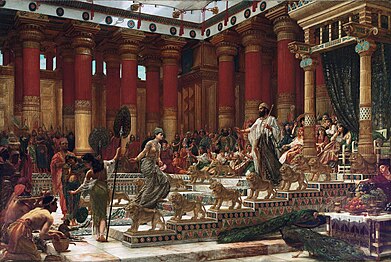

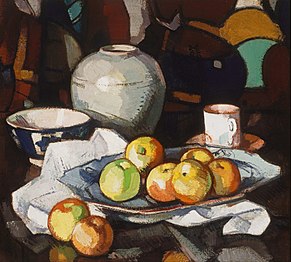

Western art

[edit]The gallery has an extensive collection of British Victorian art, including major works by Lord Frederic Leighton and Sir Edward John Poynter. It has smaller holdings of European art of the 15th to 18th centuries, including works by Peter Paul Rubens, Canaletto, Bronzino, Domenico Beccafumi, Giovanni Battista Moroni and Niccolò dell'Abbate. These works hang in the Grand Courts along with 19th-century works by Eugène Delacroix, John Constable, Ford Madox Brown, Vincent van Gogh, Auguste Rodin, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne and Camille Pissarro.[7]

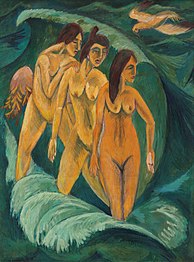

British art of the 20th century occupies a significant place in the collection together with major European figures such as Pierre Bonnard, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, Auguste Rodin, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Alberto Giacometti and Giorgio Morandi.[7]

Selected works

[edit]-

Benjamin West, Joshua passing the River Jordan with the Ark of the Covenant, 1800

-

John Constable, Landscape with goatherd and goats, 1823

-

James Tissot, The Widower, 1876

-

John William Waterhouse, Diogenes, 1882

-

Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Peasant, 1884

-

Claude Monet, Port-Goulphar, Belle-Île, 1887

-

Paul Cézanne, Banks of the Marne, 1888

-

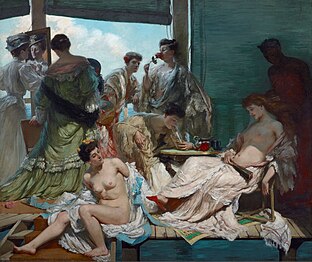

Edward Poynter, The visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon, 1890

-

Édouard Detaille, Vive L'Empereur, 1891

-

Samuel Peploe Still life – Apples and Jar, c. 1912

-

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Three Bathers, 1913

Temporary exhibitions

[edit]

Around 40 temporary exhibitions are held each year; some with an entry charge. In addition to one-off exhibitions, the gallery hosts the long running Archibald Prize, the most prominent Australian art prize, along with the Sulman, Wynne and the Dobell art prizes, among others. the gallery also exhibits ARTEXPRESS, a yearly showcase of Higher School Certificate Visual Arts Examination artworks from across New South Wales.[7]

The National

[edit]The National is a series of biennial survey exhibitions featuring contemporary artists, run as a partnership between AGNSW, Carriageworks and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA) and held across the three galleries. The inaugural edition was held in 2017.[57][58]

The National 2021: New Australian Art, the third in the series, was held between March and September 2021, featuring new and commissioned projects by 39 artists, collectives and collaborative groups. Featured artists included Vernon Ah Kee with Dalisa Pigram, Betty Muffler, Sally Smart, Alick Tipoti, Judy Watson, Judith Wright,[57] and Tom Polo.[59]

Brett Whiteley Studio

[edit]The Brett Whiteley Studio at 2 Raper Street, Surry Hills was the workplace and home of Australian artist Brett Whiteley (1939–1992). Since 1995 it has been managed as a museum by the Art Gallery of NSW.[7]

Programs

[edit]- Education

Gallery educators produce a diverse range of resources for the primary, secondary and tertiary education audiences linked to the collection and major exhibitions.[7]

- Volunteer guides

Gallery guides provide tours of the collection and exhibitions to visitors, including school groups, gallery members, corporate clients and VIPs.[7]

- Conservation

Gallery conservators undertake projects to safeguard artworks by preventing, slowing down, remedying or reversing decay and damage while ensuring artworks are safely displayed, stored or transported.[7]

- Public programs

The gallery has a program of talks, films, performances, courses and workshops as well as programs designed to increase access for people with special needs.[7]

Facilities

[edit]

- Café

- Restaurant

- Library and archive

- Study room

- Gallery Shop

- Centenary Auditorium – 90 seats

- Domain Theatre – 339 seats

Governance

[edit]The Art Gallery of NSW is a statutory body established under the Art Gallery of New South Wales Act (1980) and is a body aligned with NSW Trade & Investment. Led by a board of trustees, the gallery also provides administrative support for several other entities, each with its own legal structure: the Art Gallery of NSW Foundation, VisAsia, Brett Whiteley Foundation and Art Gallery Society of NSW.[7]

The board of trustees has nine members plus a president and vice president. An executive is composed of the gallery director, deputy directory, and three senior staff members. The Art Gallery of NSW Foundation is the gallery's major acquisition fund and the umbrella organisation for all the gallery benefactor groups and funds. It raises money from donations and bequests, invests this capital and then uses the income to purchase works of art for the collection. The Art Gallery of New South Wales has also developed a sound foundation of corporate support. It presenting partners and sponsors include Aqualand Projects, EY, Herbert Smith Freehills, JPMorgan Chase, Macquarie Group and UBS.[60]

VisAsia, the Australian Institute of Asian Culture and Visual Arts, was established to promote Asian arts and culture. It includes both the VisAsia Council and individual membership. The Brett Whiteley Foundation, promotes and encourages knowledge and appreciation of the work of the late Brett Whiteley. The Art Gallery Society of NSW is the gallery's membership organisation. Its objectives are to enhance members' enjoyment of art, and to raise funds for the gallery's collection. The society is a separate legal entity, controlled and operated by the Society Council and members.[7]

Directors

[edit]| Order | Officeholder | Position title | Start date | End date | Term in office | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eliezer Levi Montefiore | Director | 1 September 1892 | 22 October 1894 | 2 years, 51 days | [61][62][63] |

| 2 | George Edward Layton | Secretary and Superintendent | 1 January 1895 | 26 May 1905 | 10 years, 145 days | [64][65][66] |

| 3 | Gother Mann CBE | 1 July 1905 | 7 May 1913 | 23 years, 185 days | [67][68][69] | |

| Director and Secretary | 7 May 1913 | 2 January 1929 | ||||

| 4 | James MacDonald | 2 January 1929 | 13 November 1936 | 7 years, 316 days | [70][71][72][73][74] | |

| – | William Herbert Ifould (acting) | 13 November 1936 | 15 February 1937 | 94 days | [75] | |

| 5 | Will Ashton OBE | 15 February 1937 | 28 April 1944 | 7 years, 73 days | [76][77][78][79][80] | |

| – | Hector Pope Melville (acting) | 28 April 1944 | 11 July 1945 | 1 year, 74 days | [80][81] | |

| 6 | Hal Missingham AO | 11 July 1945 | 3 September 1971 | 26 years, 54 days | [82][83][84] | |

| 7 | Peter Laverty | Director | 3 September 1971 | 30 December 1977 | 6 years, 118 days | [85][86] |

| – | Gil Docking (acting) | 30 December 1977 | 17 August 1978 | 230 days | [87][88] | |

| 8 | Edmund Capon AM, OBE | 17 August 1978 | 23 December 2011 | 33 years, 128 days | [89][27][90][91][92] | |

| – | Anne Flanagan (acting) | 23 December 2011 | 4 June 2012 | 164 days | [93] | |

| 9 | Michael Brand | 4 June 2012 | present | 12 years, 237 days | [94][95][96] |

Board of trustees

[edit]The board of trustees comprises ten trustees and the president, two of which must have knowledge of, and be experienced in, the arts. The current members of the board are:[97][98][99]

| President | Term begins | Term ends |

|---|---|---|

| Michael Rose AM | 1 January 2025 | 31 December 2027 |

| Trustee | Term begins | Term ends |

| Sally Herman (Vice President) | 1 January 2019 | 31 December 2027 |

| Tony Albert | 1 January 2020 | 31 December 2025 |

| Anita Belgiorno-Nettis AM | 1 January 2020 | 31 December 2025 |

| Andrew Cameron AM | 1 January 2020 | 31 December 2025 |

| Paris Neilson | 1 January 2022 | 31 December 2027 |

| Caroline Rothwell | 1 January 2022 | 31 December 2027 |

| Keira Grant | 1 January 2023 | 31 December 2025 |

| Liz Lewin | 1 January 2023 | 31 December 2025 |

| Peter Collins AM, RFD, KC | 1 January 2025 | 31 December 2027 |

| Emile Sherman | 1 January 2025 | 31 December 2027 |

Presidents of the board

[edit]| # | President | Term | Time in office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sir Alfred Stephen GCMG, CB | 11 June 1874 – 30 January 1889 | 14 years, 233 days | [100][101][102] |

| 2 | Eliezer Levi Montefiore | 20 March 1889 – 6 September 1892 | 3 years, 170 days | [101] |

| 3 | Frederick Eccleston Du Faur | 6 September 1892 – 24 April 1915 | 22 years, 230 days | [103][104][105][106] |

| 4 | Sir James Reading Fairfax | 28 May 1915 – 28 March 1919 | 3 years, 304 days | [107][108][109] |

| 5 | Sir John Sulman | 11 April 1919 – 18 August 1934 | 15 years, 129 days | [110][111][112][113] |

| 6 | Sir Philip Whistler Street KCMG | 20 August 1934 – 11 September 1938 | 4 years, 22 days | [114][115] |

| 7 | John Lane Mullins | 23 September 1938 – 24 February 1939 | 154 days | [116][117] |

| 8 | Bertrand James Waterhouse OBE | 10 March 1939 – 23 July 1958 | 19 years, 135 days | [118][119] |

| 9 | William Herbert Ifould OBE | 23 July 1958 – 1 July 1960 | 1 year, 344 days | [101][120][121] |

| 10 | Eben Gowrie Waterhouse OBE, CMG | 1 July 1960 – 28 December 1962 | 2 years, 180 days | [122][123][124] |

| 11 | Sir Erik Langker OBE | 28 December 1962 – 7 June 1974 | 11 years, 161 days | [125][126] |

| 12 | Walter Bunning | 7 June 1974 – 16 September 1977 | 3 years, 101 days | [127][128] |

| 13 | John Nagle QC | 16 September 1977 – 11 July 1980 | 2 years, 299 days | [129] |

| 14 | Charles Benyon Lloyd Jones CMG | 11 July 1980 – 11 July 1983 | 3 years, 0 days | [130][131] |

| 15 | Michael Gleeson-White AO | 11 July 1983 – 10 July 1988 | 4 years, 365 days | [130][132] |

| 16 | Frank Lowy AO | 10 July 1988 – 31 December 1996 | 8 years, 174 days | [133][134][135] |

| 17 | David Gonski AC | 1 January 1997 – 31 December 2006 | 9 years, 364 days | [136] |

| 18 | Steven Lowy AM | 1 January 2007 – 31 December 2013 | 6 years, 364 days | [137][138] |

| 19 | Guido Belgiorno-Nettis AM | 1 January 2014 – 31 December 2015 | 1 year, 364 days | [138] |

| – | David Gonski AC | 1 January 2016 – 31 December 2024 | 8 years, 365 days | [139] |

| 20 | Michael Rose AM | 1 January 2025 – 31 December 2027 | 26 days | [140][141] |

Popular culture

[edit]At the start of the film Sirens, Hugh Grant walks past paintings in the Art Gallery of NSW, including Spring Frost by Elioth Gruner, The Golden Fleece (1894) by Tom Roberts, Still Glides the Stream and Shall Forever Glide (1890) by Arthur Streeton, Bailed Up (1895) by Tom Roberts, and Chaucer at the Court of Edward III (1847–51) by Ford Madox Brown.

See also

[edit]- Bill Boustead, senior conservator 1954–1977

- List of national galleries

- List of largest art museums

References

[edit]- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Annual Report 2022—23" (PDF). Art Gallery of NSW. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Getting here | Art Gallery of NSW". Art Gallery of NSW. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ Draffin, Nicholas (1988). "An enthusiastic amateur of the arts: Eliezer Levi Montefiore in Melbourne 1853-71" (e-journal). Art Bulletin of Victoria (28). National Gallery of Victoria. (Published online 2014, and now known as the Art Journal).

- ^ "Eliezer Levi Montefiore". The Baruch Lousadas and the Barrows. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "New South Wales Academy of Art". Trove. National Library of Australia. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Bergman, G.F.J. "Montefiore, Eliezer Levi (1820–1894)". Eliezer Levi Montefiore. ANU. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

This article was first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, (MUP), 1974

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah "Home :: Art Gallery NSW". nsw.gov.au.

- ^ a b Russell, Roslyn (2008). "Eliezer Montefiore – From Barbados to Sydney" (PDF). National Library of Australia News. December 2008 (p.13): 11–14. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b "Act No 54 (1899) Library and Art Gallery" (PDF). Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII). Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ a b Stuart, Geoff (1993). Secrets in stone: discover the history of Sydney. Surry Hills, Sydney: Brandname Properties. pp. 119–120. ISBN 0-646-13994-0.

- ^ "A temple to art, 1896–1909", Art Gallery of New South Wales

- ^ "The names on the exterior of the building", Art Gallery of New South Wales

- ^ a b Free, Renée (January 1972). "Late Victorian, Edwardian and French Sculptures". Art Gallery of NSW Quarterly: 651. ISSN 0004-3192.

- ^ Irvine, Louise; Atterbury, Paul (1998). Gilbert Bayes : sculptor, 1872–1953. Somerset, England: Yeovil. p. 127. ISBN 9780903685641.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act (Act No. 1 1958)" (PDF). Australasian Legal Information Institute (Austlii). Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "Exchange of Notes constituting an Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the People's Republic of China amending the Agreement concerning the Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People's Republic of China of 23 June 1976 ATS 32 of 1977 " Archived 15 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Australasian Legal Information Institute, Australian Treaties Library. Retrieved on 15 April 2017.

- ^ "The Chinese exhibition : a selection of recent archaeological finds of the People's Republic of China; National Gallery of Victoria Melbourne, 19 January/6 March, 1977; the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 25 March/8 May, 1977; the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 9 June/29 June, 1977. – Version details". Trove. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act 1980". Australasian Legal Information Institute (Austlii). Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". www.abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 6 March 2001. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

Tuesday February 27, 2001. Australia may have art stolen by Nazis. It has been revealed some artwork looted by the Nazis from Jewish families during WWII might have ended up in Australia. The New South Wales Art Gallery, one of the first Australian institutions to review its collection, says nine of the gallery's 40,000 artworks could have been among the many paintings stolen by the Nazis. New South Wales Premier Bob Carr, speaking in Sydney this morning, says while the wrongs of the past cannot be erased, art galleries and governments around the world must try and return Nazi-looted artworks to their rightful owners. Among the nine paintings identified as possible contraband are Georges Braque's Landscape with Houses and Ernst Kirchner's Three Bathers.

- ^ "Long shadow of the Nazi art plunderers". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 14 April 2001. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

The NSW Art Gallery has nine European works in its collection with gaps in the provenance from 1933-45. These include Georges Braque's Landscape with Houses, Raoul Dufy's Poppyfield at Lourdes, Ernst Kirchner's Three Bathers and an Alexander Rodchenko titled Composition.

- ^ Wallace, Natasha (15 June 2006). "Sketch or painting? Judge gives it the brush-off". The Age. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Art Crime Alert Masterwork Stolen in Australia". Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) (USA). 30 July 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Jinman R., Morgan C. Dutch master stolen Sydney Morning Herald 14 June 2007.

- ^ Taylor, Andrew (20 May 2012). "Search for stolen masterpiece ends". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Barlow, Karen NSW Gallery Defends Security System after theft of 17th century artwork ABC The World Today, 14 June 2007. Accessed on 14 June 2007

- ^ Laurie, Victoria (22 February 2022). "Neil Balnaves, Australian philanthropist and major arts patron dies aged 77 after boating accident" (Audio (20 mins) + text). ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ a b Morgan, Clare (3 August 2011). "Capon confirms retirement". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ Ruiz, Cristina. "Sydney art gallery sizes up its future". The Art Newspaper. Vol. 248, July–August 2013 (Published online: 2 August 2013). Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "Jury's decided, AGNSW's expansion now awaits government approval". Editorial Desk AAU. Architecture Media Pty Ltd. 14 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 January 2015, pp. 10–11.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Five architects selected for Stage Two of Sydney Modern Project". nsw.gov.au.

- ^ Power, Julie (5 September 2015). "Landscape architects McGregor Coxall chosen for Sydney Modern gardens". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ Editorial (29 November 2015). "Paul Keating vs the Sydney Modern: the public must decide". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Andrew (20 February 2016). "Culture wars: Powerhouse debate pits east against west". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ "Launching tonight: Volume, a festival of sound and vision at the Art Gallery of New South Wales". Art Gallery of NSW. 22 September 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "Volume festival reveals massive free program of music, film and dance". Art Gallery of NSW. 15 August 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Art Gallery of New South Wales: The Building". nsw.gov.au. Archived from the original on 12 July 2009.

- ^ a b Maisy Stapleton, ed. (1987). Australia's first parliament, Parliament House, New South Wales (2nd ed.). Sydney, NSW: Parliament NSW. pp. 72–75. ISBN 073053183X.

- ^ "The Captain Cook Wing 1968—72". Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Extensions to the Art Gallery of New South Wales by Richard Johnson of Johnson Pilton Walker". Architecture Bulletin: 18–19. September–October 2003.

- ^ Capon, Edmund (2003). "A New Light on Asian Art" (Press release). Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ O'Rouke, Jim (18 July 2004). "Controversial building takes design awards". Sun Herald. pp. 41–43.

- ^ "Awards". Johnson Pilton Walker. 2011. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Sexton, Jennifer (26 May 2000). "Gallery receives belated millions". The Australian.

- ^ Dumas, Daisy (27 May 2015). "Tokyo's SANAA architects win Art Gallery of NSW Sydney Modern design competition". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ Andersons, Andrew (4 March 2016). "This is why we shouldn't build the Art Gallery of NSW Sydney Modern extension on the Domain". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ Keating, Paul (25 November 2015). "Michael Brand's plan for the Art Gallery of NSW is about money, not art". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Austin, Clive (Spring 2016). "Sydney Modern Update". The Gardens (110). Foundation and Friends of the Botanic Gardens Ltd.: 3. ISSN 1324-8219.

- ^ Austin, Clive (Winter 2018). "From the Chairman – New Developments". The Gardens: 3. ISSN 1324-8219.

- ^ a b c d "The Sydney Modern project is finally open. Has the Art Gallery of NSW's $344m expansion paid off?". The Guardian. 2 December 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ a b "'Most significant build since the Opera House': $344 million new art gallery opens in Sydney". ABC News. 1 December 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "Aboriginal language names for Art Gallery of New South Wales buildings". Art Gallery of NSW. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Yiribanna Gallery". Sydney Barani. 20 January 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ "Hetti Perkins, b. 1965". National Portrait Gallery people. 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Yiribana Gallery". Art Gallery of NSW. 17 January 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ Works cited in the document '100 masterpieces of Australian painting (1973)', Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved on 9 January 2011.

- ^ a b "The National 2021: New Australian Art". The National. 5 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "About". The National. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Paton, Justin. "Artists". The National. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Corporate sponsorship". www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ "Government Gazette Appointments and Employment". New South Wales Government Gazette. No. 627. New South Wales, Australia. 2 September 1892. p. 7072. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "A marble portrait bust of E.L. Montefiore by Theodora Cowan is in the gallery's collection". Art Gallery of New South Wales.

- ^ "Death of Mr. E. L. Montefiore". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 23 October 1894. p. 5. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The National Art Gallery". The Daily Telegraph. New South Wales, Australia. 2 January 1895. p. 4. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Public Service Gazette". The Daily Telegraph. New South Wales, Australia. 2 September 1899. p. 7. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Personal". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 27 May 1905. p. 11. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Government Gazette Appointments and Employment". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 484. New South Wales, Australia. 15 September 1905. p. 6296. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Appointment". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 71. New South Wales, Australia. 7 May 1913. p. 2779. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Retention of Services". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 150. New South Wales, Australia. 2 November 1928. p. 4754. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 24 October 1928. p. 14. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery Director". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 5 December 1928. p. 16. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 5 December 1928. p. 22. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "New Director for National Gallery". The Daily Telegraph. New South Wales, Australia. 1 January 1929. p. 7. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Resignations". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 190. New South Wales, Australia. 20 November 1936. p. 4860. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery. Mr. Ifould Acting Director". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 16 November 1936. p. 8. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Appointments". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 20. New South Wales, Australia. 12 February 1937. p. 680. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "National Art Gallery Director". The Labor Daily. New South Wales, Australia. 17 February 1937. p. 8. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mr. Will Ashton". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 22 January 1937. p. 10. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Resignation of Gallery Director". The Daily Telegraph. New South Wales, Australia. 3 July 1945. p. 11. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "Art Director Leaves Today". The Daily Telegraph. New South Wales, Australia. 28 April 1944. p. 10. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Acting Director of Art Gallery". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 17 April 1944. p. 3. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Special Gazette Under the 'Public Service Act, 1902'". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 95. New South Wales, Australia. 14 September 1945. p. 1649. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Sydney Art Gallery Director". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 13 July 1945. p. 5. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "New Director for Sydney Art Gallery". The Herald. Victoria, Australia. 12 July 1945. p. 8. Retrieved 17 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Dale, David (3 September 1971). "Artist is new gallery chief". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 1.

- ^ "Resignations". Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales. New South Wales, Australia. 23 March 1978. p. 1005. Retrieved 25 March 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Bright, Gregory (14 January 1978). "They gave us family trusts". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 27.

- ^ Davies, Linda (22 January 2016). "Gypsy life led Gil Docking into feted arts administration career – Gil Docking 1919-2015". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "In Brief: Inquiry into wage fixation ends". The Canberra Times. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 18 August 1978. p. 3. Retrieved 25 March 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Frykberg, Ian (18 August 1978). "Director has ambitious plans for NSW gallery". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 3.

- ^ "Edmund Capon to Open Exhibition" (Media Release). Sculptures in the Garden. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Dingle, Sarah (3 August 2011). "Gallery veteran Capon steps down". ABC News. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Appointment of acting director". Art Gallery of New South Wales. 2011. Archived from the original (Media Release) on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Fortescue, Elizabeth (10 February 2012). "Australian Dr Michael Brand is the new director for the Art Gallery of NSW". The Telegraph. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Michael Brand appointed Director of Art Gallery of NSW". Art Gallery of New South Wales. 10 February 2012. Archived from the original (Media Release) on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Director Michael Brand to step down next year" (Media Release). Art Gallery of NSW. 29 October 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ "Art Gallery of NSW Board of Trustees". Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ "New board members appointed to NSW cultural institutions" (Media Release). NSW Government (Minister for the Arts). 22 December 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ "New leadership at NSW Cultural Institutions" (Media Release). NSW Government. Minister for the Arts. 10 December 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ "New South Wales Academy of Art". The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser. New South Wales, Australia. 20 June 1874. p. 784. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c Reed, Stewart (2013). "Policy, taste or chance? – acquisition of British and Foreign oil paintings by the Art Gallery of New South Wales from 1874 to 1935 (MArtsAdmin Thesis)". UNSWorks.unsw.edu.au. University of New South Wales. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Government Gazette Appointments and Employment". New South Wales Government Gazette. No. 214. New South Wales, Australia. 16 April 1889. p. 2863. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Mr. E. Du Faur". The Daily Telegraph. New South Wales, Australia. 2 January 1901. p. 9. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Death of Mr. Du Faur". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 26 April 1915. p. 8. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Personal". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 29 May 1915. p. 14. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Du Faur, Frederick Eccleston (1832–1915)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. 1972. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "National Art Gallery". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 1 June 1915. p. 8. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Death of Sir James Fairfax". Sydney Mail. New South Wales, Australia. 2 April 1919. p. 8. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Late Sir James Fairfax. National Art Gallery Trustees". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 12 April 1919. p. 17. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Personal". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 12 April 1919. p. 17. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 19 April 1919. p. 11. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Sir John Sulman". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 20 August 1934. p. 8. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Sir John Sulman, K.B." The Daily Telegraph. New South Wales, Australia. 3 June 1924. p. 7. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Personal". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 6 October 1934. p. 14. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Death of Sir Philip Street". Sydney Mail. New South Wales, Australia. 14 September 1938. p. 11. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Personal". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 24 September 1938. p. 10. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "John Lane Mullins Dies at 82". The Sun. New South Wales, Australia. 24 February 1939. p. 7. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery President". The Sun. New South Wales, Australia. 10 March 1939. p. 2. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Gallery Retirement". The Sydney Morning Herald. 3 July 1958. p. 5.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act, 1958". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 64. New South Wales, Australia. 27 June 1958. p. 1920. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Jean F., Arnot (1983). "Ifould, William Herbert (1877–1969)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act, 1958". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 75. New South Wales, Australia. 24 June 1960. p. 1970. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Gallery Trustees Retire". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 November 1962. p. 11.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act, 1958". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 130. New South Wales, Australia. 28 December 1962. p. 3867. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act, 1958". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 21. New South Wales, Australia. 26 February 1971. p. 552. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Clifford-Smith, Silas. "Sir Erik Langker b. 3 November 1898". Design & Art Australia Online. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Spearritt, Peter (1993). "Bunning, Walter Ralston (1912–1977)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act, 1958". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 68. New South Wales, Australia. 7 June 1974. p. 2153. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "New President". The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 September 1977. p. 4.

- ^ a b "Banker heads art board". The Sydney Morning Herald. 28 July 1983. p. 5.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act, 1980". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 93. New South Wales, Australia. 11 July 1980. p. 3569. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act 1980". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 120. New South Wales, Australia. 18 July 1986. p. 3400. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act 1980". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 134. New South Wales, Australia. 19 August 1988. p. 4348. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act 1980—Appointment of President of the Art Gallery of New South Wales Trust". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 180. New South Wales, Australia. 20 December 1991. p. 10587. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Art Gallery of New South Wales Act 1980". Government Gazette Of The State Of New South Wales. No. 174. New South Wales, Australia. 23 December 1994. p. 7610. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Buke, Kelly (28 December 1996). "New chiefs named for State's cultural boards". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 5.

- ^ "Steven Lowy New President" (Media Release). Art Gallery of New South Wales. 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Steven Lowy to retire as President of Art Gallery of NSW". Art Gallery of New South Wales. 13 September 2013. Archived from the original (Media Release) on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Andrew (8 December 2015). "David Gonski appointed to lead the Art Gallery of NSW board". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Bailey, Michael (13 December 2024). "The two things David Gonski will miss as he exits gallery role". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ Morris, Linda (10 December 2024). "Who's in, who's out as Labor figures head cultural leadership shake-up". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

Further reading

[edit]- Thomas, Daniel (2011). "Art museums in Australia: a personal account". Understanding Museums. Includes link to PDF of the article "Art museums in Australia: a personal retrospect" (originally published in Journal of Art Historiography, no. 4, June 2011).

External links

[edit]- Official website

- "Art Gallery of New South Wales". History and Archives: Historic Buildings. City of Sydney. 2004. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- Art Gallery of New South Wales Artabase page Archived 6 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Virtual Tour of Art Gallery of New South Wales Archived 9 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Virtual tour of the Art Gallery of New South Wales provided by Google Arts & Culture

![]() Media related to Art Gallery of New South Wales at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Art Gallery of New South Wales at Wikimedia Commons

- Art Gallery of New South Wales

- Government agencies of New South Wales

- Art museums and galleries in Sydney

- Neoclassical architecture in Australia

- Art museums and galleries established in 1897

- 1897 establishments in Australia

- Walter Liberty Vernon buildings in Sydney

- Buildings and structures awarded the Sir John Sulman Medal