Apple Corps

Apple Corps' logo, featuring a Granny Smith apple | |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry |

|

| Founded | 20 June 1963 (as Beatles Ltd.)

17 November 1967 (as Apple Music Ltd.) 2 April 1968 (as Apple Corps) |

| Founder | The Beatles |

| Headquarters | London, United Kingdom |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Jeff Jones (CEO) |

| Revenue | £18.6 million (2019) |

| £5.5 million (2019) | |

| £4.4 million (2019) | |

| Owner | The Beatles (Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, estates of John Lennon and George Harrison) |

| Subsidiaries | List of Apple Corps Subsidiaries |

| Website | applecorps |

Apple Corps Limited is a multi-armed multimedia corporation founded in London in January 1968 by the members of the Beatles to replace their earlier company (Beatles Ltd.) and to form a conglomerate. The name is a pun for its pronunciation "apple core".[1] Its chief division is Apple Records, which was launched in the same year. Other divisions included Apple Electronics, Apple Films, Apple Publishing and Apple Retail, whose most notable venture was the short-lived Apple Boutique, on the corner of Baker Street and Paddington Street in central London. Apple's headquarters in the late 1960s was at the upper floors of 94 Baker Street, after that at 95 Wigmore Street, and subsequently at 3 Savile Row. The last of these addresses was also known as the Apple Building, which was home to the Apple studio.

From 1970 to 2007, Apple's chief executive was former Beatles road manager Neil Aspinall, although he did not officially bear that title until Allen Klein had left the company. The current CEO is Jeff Jones. In 2010, Apple Corps ranked number two on the Fast Company magazine's list of the world's most innovative companies in the music industry, thanks to the release of The Beatles: Rock Band video game and the remastering of the Beatles' catalogue.[2]

History

[edit]The Beatles' accountants had informed the group that they had £2 million that they could either invest in a business venture or else lose to the Inland Revenue, because corporate/business taxes were lower than their individual tax bills.[3] According to Peter Brown, personal assistant to Beatles' manager Brian Epstein, activities to find tax shelters for the income that the Beatles generated began as early as 1963–64, when Walter Strach[4] was put in charge of such operations.[5] First steps into that direction were the foundation of Beatles Ltd and, in early 1967, Beatles and Co.[3]

The Beatles' publicist, Derek Taylor, remembered that Paul McCartney had the name for the new company when he visited Taylor's company flat in London: "We're starting a brand new form of business. So, what is the first thing that a child is taught when he begins to grow up? A is for Apple". McCartney then suggested the addition of Apple Core, but they could not register the name, so they used "Corps" (having the same pronunciation).[6] McCartney later revealed that he had been inspired by René Magritte's painting Le Jeu de Mourre, featuring an apple with the words "Au revoir" painted on it.[6] Harriet Vyner's 1999 book about the late London art dealer Robert Fraser, "Groovy Bob", contains this anecdote by McCartney about the first time he laid eyes on the painting that would inspire the company logo in 1967:[7]

In my garden at Cavendish Avenue, which was a 100-year-old house I'd bought, Robert was a frequent visitor. One day he got hold of a Magritte he thought I'd love. Being Robert, he would just get it and bring it. I was out in the garden with some friends. I think I was filming Mary Hopkin with a film crew, just getting her to sing live in the garden, with bees and flies buzzing around, high summer. We were in the long grass, very beautiful, very country-like. We were out in the garden and Robert didn't want to interrupt, so when we went back in the big door from the garden to the living room, there on the table he'd just propped up this little Magritte. It was of a green apple. That became the basis of the Apple logo. Across the painting Magritte had written in that beautiful handwriting of his 'Au revoir'. And Robert had split. I thought that was the coolest thing anyone's ever done with me".

Formation

[edit]On the founding of Apple, John Lennon commented: "Our accountant came up and said 'We got this amount of money. Do you want to give it to the government or do something with it?' So we decided to play businessmen for a bit because we've got to run our own affairs now. So we've got this thing called 'Apple' which is going to be records, films, and electronics – which all tie up".[8]

Stefan Granados wrote in Those Were the Days: An Unofficial History of the "Beatles" Apple Organization 1967–2001, on the various processes that led to the formation of Apple Corps:

The first step towards creating this new business structure was to form a new partnership called Beatles and Co. in April 1967. To all intents and purposes, Beatles and Co. was an updated version on the Beatles' original partnership, Beatles Ltd. Under the new arrangement, however, each Beatle would own 5% of Beatles and Co. and a new corporation owned collectively by all four Beatles [which would soon be known as Apple] would be given control of the remaining 80% of Beatles and Co. With the exception of individual songwriting royalties, which would still be paid directly to the writer or writers of a particular song, all of the money earned by the Beatles as a group would go directly to Beatles and Co. and would thus be taxed at a far lower corporate tax rate".[9][10]

Now that a new business structure was found with a lower tax rate, Epstein mused what to do with it to justify it to the authorities, and originally thought of it mostly as a merchandising company, according to Lennon's first wife, Cynthia: "The idea Brian came up with was a company called Apple. His idea was to plough their money into a chain of shops not unlike Woolworth's in concept: Apple boutiques, Apple posters, Apple records. Brian needed an outlet for his boundless energy".[11] Personal assistant to Epstein, Alistair Taylor remembered:[12]

We set up an 'Executive Board' of Apple before Brian died, including Brian, the accountant, a solicitor, Neil Aspinall, myself, and then sat down to work out ways of spending the money. One big idea was to set up a chain of shops designed only to sell cards: birthday cards, Christmas cards, anniversary cards. When the boys heard about that they all condemned the scheme as the most boring yet. Sure that they could come up with much better brainwaves, they began to get involved themselves".[13]

In the middle of setting up the new company, manager Epstein died unexpectedly in what seemed an accidental sleeping pills overdose on 27 August 1967, which pressed the Beatles to accelerate their plans to gain control of their own financial affairs. In addition to providing an umbrella to cover the Beatles' own financial and business affairs, Apple was intended to provide a means of financial support to anyone in the wider world struggling to get 'worthwhile' artistic projects off the ground. According to Granados, this idea probably originated with Paul McCartney as the Beatle most engaged in London's local avant-garde scene, "McCartney was among the best-known exponents of swinging London".[14] Ringo Starr was quoted as saying of the venture:[15]

We tried to form Apple with [Brian's brother] Clive Epstein, but he wouldn't have it... He didn't believe in us I suppose... He didn't think we could do it. He thought we were four wild men and we were going to spend all his money and make him broke. But that was the original idea of Apple – to form it with NEMS... We thought now Brian's gone let's really amalgamate and get this thing going, let's make records and get people on our label and things like that. So we formed Apple and they formed NEMS, which is exactly the same thing as we are doing. It was a family tie and we thought it would be a good idea to keep it in".

McCartney at first had obviously intended to use Epstein's music publishing company NEMS Enterprises for these plans, but after Epstein's death it was learned that Australian Robert Stigwood was trying to get hold of NEMS.[16] All four Beatles were not in favour of such an outcome, as McCartney had previously told Epstein in 1967:[17]

We said, 'In fact, if you do, if you somehow manage to pull this off, we can promise you one thing. We will record God Save the Queen for every single record we make from now on and we'll sing it out of tune. That's a promise. So if this guy buys us, that's what he's buying'".

They hurried to set up Apple instead, and seeing that the Beatles would not be part of the NEMS package, Stigwood went to form his own company, RSO Records. The Apple logo was designed by Gene Mahon, with illustrator Alan Aldridge transcribing the copyright notice to appear on record releases. In January 1968, Beatles Ltd. officially changed its name to Apple Corps. Ltd. and registered the Apple trademark in forty-seven countries[18] In February the company also registered Apple Electronics, Apple Films Ltd., Apple Management, Apple Music Publishing, Apple Overseas, Apple Publicity, Apple Records, Apple Retail, and Apple Tailoring Civil and Theatrical with the intent on focusing on five divisions: records, electronics, film, publishing and retailing.

Lennon and McCartney introduced their new business concept on a press conference held on 14 May 1968 in New York City, with McCartney saying it would be, "A beautiful place where you can buy beautiful things… a controlled weirdness… a kind of Western communism".[19][20] Lennon said, "It's a company we're setting up, involving records, films, and electronics, and – as a sideline – manufacturing or whatever. We want to set up a system where people who just want to make a film about anything, don't have to go on their knees in somebody's office, probably yours".[21] McCartney also said: "It's just trying to mix business with enjoyment. We're in the happy position of not needing any more money. So for the first time, the bosses aren't in it for profit. We've already bought all our dreams. We want to share that possibility with others".[21]

Early administration

[edit]For the first few months of Apple's existence, it did not even have an office. Most of the company's business was conducted from the NEMS building. It was not until the autumn of 1967 that Apple finally opened a London office. Since the Beatles already owned a four-story building at 94 Baker Street that had been purchased as an investment property by their accountants, they decided that Baker Street was as good a location as any for Apple. In September they set up an office for Apple Publishing in the Baker Street building. With Epstein's death, there was nobody in the Beatles' inner circle with business acumen who could manage the company, and, as with their band affairs, the Beatles decided that they would manage it themselves.

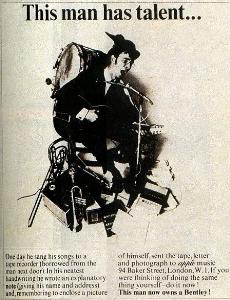

In December 1967, shortly after Epstein's death, Lennon asked Alistair Taylor to work as General Manager for Apple. It was during this period that Taylor appeared in the famous advertisement to promote Apple asking for new artists. Designed by McCartney, it showed him disguised as a one-man band, claiming: "This man has talent..." The publication in the New Musical Express and Rolling Stone brought an avalanche of applicants. The mail room, telephone switchboard, and conference rooms became jammed at all hours with "artists" begging the Beatles to give them money. George Harrison would later lament that "We had every freak in the world coming in there". Many of these supplicants received the investments they sought and were never heard from again.

Even though Apple was declared the most successful new record company of the year for 1968, before long the band members' ignorance of finance and administration combined with their naive, utopian mission of funding struggling, unknown artists left Apple Corps with no solid business plan.

The Beatles' naivete and inability to keep track of their own accounts was also eagerly exploited by the employees of Apple, who purchased drugs and alcoholic beverages, company lunches at expensive London restaurants, and international calls made regularly on office telephones, all of which would be treated as business expenses. Writers Alan Clayson and Spencer Leigh described the owners' hopelessness in managing their own creation:

Out of his depth, a Beatle might commandeer a room at Savile Row, stick to conventional office hours and play company director until the novelty wore off. Initially, he'd look away from the disgusting realities of the half-eaten steak sandwich in a litter bin; the employee rolling a spliff of best Afghan hash; the typist who span out a single letter (in the house style, with no exclamation marks!) all morning before 'popping out' and not returning until the next day. A great light dawned. 'We had, like, a thousand people that weren't needed,' snarled Ringo, 'but they all enjoyed it. They were all getting paid for sitting around. We had a guy there just to read the tarot cards, the I Ching. It was craziness".[22]

Aspinall finally agreed to direct the company on a temporary basis, simply so that someone would finally be in charge. When, in 1969, the Beatles engaged Klein as their manager, he also inherited the chairmanship of Apple Corps, which led to an immediate streamlining of company affairs: "Overnight, glib lack of concern deferred to pointed questions," wrote Clayson & Leigh. "Which typist rings Canberra every afternoon? Why has so-and-so given himself a raise of 60 pounds a week? Why is he seen only on payday? Suddenly, lunch meant beans-on-toast in the office kitchen instead of Beluga caviar from Fortnum & Mason".[23]

Beatles break-up and beyond

[edit]The first two years of the company's existence also coincided with a marked worsening of the Beatles' relationships with each other, ultimately leading to the break-up of the band in April 1970. Apple quickly slid into financial chaos, which was resolved only after many years of litigation. When the Beatles' partnership was dissolved in 1975, dissolution of Apple Corps was also considered, but it was decided to keep it operating, while effectively retiring or mothballing all its divisions. The company is currently headquartered at 27 Ovington Square, in London's prestigious Knightsbridge district. Ownership and control of the company remains with McCartney, Starr and the estates of Lennon and Harrison.

Apple Corps has had a long history of trademark disputes with Apple Computer (now Apple Inc.). The dispute was finally resolved in 2007, with Apple Corps transferring ownership of the "Apple" name and all associated trademarks to Apple Inc., and Apple Inc. exclusively licensing these back to the Beatles' company. In April 2007, Apple also settled a long-running dispute with EMI and announced the retirement of chief executive Aspinall.[24][25] Aspinall was replaced by Jeff Jones.[26]

Subsidiaries

[edit]Apple Corps operated in various fields, mostly related to the music business and other media, through a number of subsidiaries.

Apple Electronics

[edit]Apple Electronics was the electronics division of Apple Corps, founded as Fiftyshapes Ltd., at 34 Boston Place, Westminster, London. It was headed by Beatles' associate Yanni Alexis Mardas, whom Lennon had nicknamed Magic Alex.[27] Intending to revolutionise the consumer electronics market, largely through products based on Mardas' unique and, as it turned out, commercially impractical designs, the electronics division did not make any breakthroughs. After the dismissal of Mardas in 1969, during Klein's 'house-cleaning' of Apple Corps, Apple Electronics fell victim to the same forces that troubled the company as a whole, including the impending Beatles' break-up. It was later estimated that Mardas' ideas and projects had cost the Beatles at least £300,000 (worth approximately £6.24 million in 2023).[28][29][30]

Apple Films

[edit]

Apple Films is the film-making division of Apple Corps. Its first production was The Beatles' 1967 TV movie Magical Mystery Tour. The Beatles' films Yellow Submarine and Let it Be were also produced under Apple Films. Other notable releases included Raga (a 1971 documentary on Ravi Shankar), The Concert for Bangladesh (1972) and Little Malcolm (1974). The latter, produced by George Harrison, included the song "Lonely Man" by Dark Horse Records band Splinter. Apple Films was also responsible for producing Apple Corps' televised promotions.

The following is a list of releases from Apple Films, usually in the role of production company.[31]

- Magical Mystery Tour (1967). Starring the Beatles; produced and directed by the Beatles; filmed September–October 1967; 54 mins. World premiere: BBC1 (TV), 26 December 1967.

- Yellow Submarine (1968). Animated film featuring the Beatles; produced by Al Brodax; directed by George Dunning; animation designed by Heinz Edelmann; written by Lee Minoff, Al Brodax, Jack Mendelsohn and Erich Segal; 85 mins. Distributed by United Artists. World/UK premiere: London, 17 July 1968. US premiere: New York, 13 November 1968.

- Did Britain Murder Hanratty? (1969) A 40-minute documentary film commissioned by John Lennon and produced by Apple Films Limited. The only public screening of the complete film was in the crypt of St Martin-in-the-Fields Church, London on 17 February 1970.[32][33]

- Let It Be (1970). Documentary featuring the Beatles; produced by Neil Aspinall; directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg; filmed January–February 1969; 88 mins. Distributed by United Artists. World/US premiere: New York, 13 May 1970. UK premiere: London, 20 May 1970.

- Raga (1971). Documentary featuring Ravi Shankar, Yehudi Menuhin, George Harrison and Ustad Alauddin Khan; produced by Howard Worth and Nancy Bacal; directed by Howard Worth; 96 mins. Distributed by Apple Films. World/US premiere: New York, 23 November 1971.

- The Concert for Bangladesh (1972). Concert documentary featuring George Harrison, Ravi Shankar, Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan, Ali Akbar Khan, Billy Preston, Eric Clapton and Leon Russell; produced by George Harrison and Allen Klein; directed by Saul Swimmer; filmed July–August 1971; 103 mins. Distributed by 20th Century Fox. World/US premiere: New York, 23 March 1972. UK premiere: London, 27 July 1972.

- Born to Boogie (1972). Documentary featuring Marc Bolan, T. Rex, Elton John and Ringo Starr; produced and directed by Ringo Starr; filmed March–April 1972. Distributed by Apple Films. World/UK premiere: London, 18 December 1972.

- Son of Dracula (1974). Starring Harry Nilsson, Ringo Starr, Suzanna Leigh, Freddie Jones and Dennis Price; produced by Ringo Starr, Jerry Gross and Tim Van Rellim; directed by Freddie Francis; screenplay by Jennifer Jayne; filmed August–October 1972; 90 mins. Distributed by Cinemation Industries. World/US premiere: Atlanta, GA, 19 April 1974.

- Little Malcolm (1974). Starring John Hurt, John McEnery, Raymond Platt, Rosalind Ayres and David Warner; produced by George Harrison and Gavrick Losey; directed by Stuart Cooper; screenplay by David Halliwell and Derek Woodward; 109 mins. Distributed by Apple Films. World/European premiere: Berlin, July 1974.

Apple Publishing

[edit]Apple's music publishing arm predated the record company. In September 1967, the first artists to be signed by Apple Publishing were two songwriters from Liverpool. Paul Tennant and David Rhodes were offered a contract after meeting McCartney in Hyde Park.[34] They were advised to form a band by Epstein after he and Lennon heard their demos, calling the group Focal Point.[35] Epstein was to have managed the band but died before he could become involved. Terry Doran MD of Apple Publishing became their manager and they were signed by Deram Records.[36] Apple published the group's self-penned songs from early 1968.[37] Another early band on its publishing roster was the group Grapefruit.[38]

Apple Publishing Ltd. was also used as a publishing stop-gap by Harrison and Starr, as they sought to shift control of their own songs away from Northern Songs, in which their status was little more than paid writers. (Harrison later started Harrisongs, and Starr created Startling Music). Apple's greatest publishing successes were the Badfinger hits "No Matter What", "Day After Day" and "Baby Blue", all written by group member Pete Ham, and Badfinger's "Without You", a song penned by Ham and Badfinger bandmate Tom Evans. "Without You" became a worldwide No. 1 chart hit for Harry Nilsson in 1972 and Mariah Carey in 1993. In 2005, however, Apple lost the US publishing rights for the work of Ham and Evans. Those rights were transferred to Bug Music, now a branch of BMG Rights Management.[39]

Apple also undertook publishing duties, at various times, for other Apple artists, including Yoko Ono, Billy Preston and the Radha Krishna Temple. Apple received a large number of demo tapes; some songs were published, some were issued on other labels and only Benny Gallagher & Lyle were retained as in-house writers before going on to co-found McGuinness Flint. Many of these demos have been collected on a series of CDs released by Cherry Red Records. They are entitled 94 Baker Street,[40] An Apple for the Day,[41] Treacle Toffee World,[42] Lovers from the Sky: Pop Psych from the Apple Era 1968-1971 and 94 Baker Street Revisited: Poptastic Sounds from the Apple Era 1967-1968.

Apple Books was largely inactive and had very few releases. One notable release was the book that accompanied the initial pressing of the Let It Be album, titled The Beatles Get Back, containing photographs by Ethan Russell and text by Rolling Stone writers Jonathan Cott and David Dalton. Although the book was credited to Apple Publishing, all of the work on the project was actually done by freelancers.[43][44][45][46][47]

Apple Records and Zapple Records

[edit]From 1968 onwards, new releases by the Beatles were issued by Apple Records, although the copyright remained with EMI, and Parlophone/Capitol catalogue numbers continued to be used. Apple releases of recordings by artists other than the Beatles, however, used a new set of numbers, and the copyrights were held mostly by Apple Corps Ltd. More than a "vanity label", Apple Records developed an eclectic roster of their own, releasing records by artists as diverse as Indian sitar guru Ravi Shankar, Welsh easy listening singer Mary Hopkin, the power-pop band Badfinger, classical music composer John Tavener, soul singer Billy Preston, folk singer James Taylor, R&B singer Doris Troy, New York underground rock band Elephant's Memory, original bad girl of rock and roll Ronnie Spector, rock singer Jackie Lomax, the Modern Jazz Quartet, and London's Radha Krishna Temple.

Since Apple's inception, McCartney and Lennon had been very interested in launching a budget-line label to issue what would essentially be known three decades later as "audio books". In October 1968, Apple hired Barry Miles, who co-owned the Indica bookshop with John Dunbar and Peter Asher, to manage the proposed spoken-word label. The initial idea of Zapple Records was that it would release avant-garde and spoken word records at a reduced price that would be comparable to that of a paperback novel. While the idea looked good on paper, the reality was that when the few records actually put out by Zapple finally made it into the shops, they were priced like any other full-priced music album.[48] Zapple Records was started on 3 February 1969, but after Klein was brought in to run Apple Corps' affairs, it was closed down after just two releases: Lennon and Ono's Unfinished Music No. 2: Life with the Lions, and Harrison's Electronic Sound.[49]

Apple Retail

[edit]The Apple Boutique was a retail store, located at 94 Baker Street in London, and was one of the first business ventures by Apple Corps. Lennon's schoolfriend Pete Shotton was hired as manager, and the Dutch design collective The Fool were brought in to design the store and much of the merchandise.[50] The store opened to much fanfare on 7 December 1967, with Lennon and Harrison attending (Starr was filming, and McCartney was on holiday). The boutique was never profitable, largely due to shoplifting, by customers and its own staff.[51] After Shotton resigned, John Lyndon took over but his management experience could not save the enterprise.[52] The store's remaining stock was liquidated by giving it away, after the individual Beatles had taken whatever they liked the night before its closure.[51] The boutique closed its doors on 31 July 1968.[52]

Apple Studio

[edit]

Apple Studio was a recording studio, purchased in 1968 and located in the basement of the Apple Corps headquarters at 3 Savile Row.[53] The facility was renamed Apple Studios after its expansion in 1971.

Originally designed by Alex Mardas, of Apple Electronics, the initial installation proved to be unworkable − with almost no standard studio features such as a patch bay, or a talkback system between the studio and the control room, let alone Mardas' promised innovations − and had to be scrapped. Nevertheless, the Beatles recorded and filmed portions of their album Let It Be in the Apple Studio, with equipment borrowed from EMI; during takes they had to shut down the building's central heating, also located in the basement, because the lack of soundproofing allowed the heating system to be heard in the studio.

The redesign and rebuilding of the basement to accommodate proper recording facilities was overseen by former EMI engineer Geoff Emerick, and took eighteen months at an estimated cost of $1.5 million. Beatles' technical engineer Claude Harper aided on the project, as well.[54] The studio reopened on 30 September 1971 and now included its own natural echo chamber, a wide range of recording and mastering facilities, and could turn out mono, stereo and quadrophonic master tapes and discs. In 1971, it would have cost £37 an hour (equivalent to £700 in 2023)[28] to record to 16-track, £29 an hour (equivalent to £500 in 2023)[28] to mix to stereo, and £12 (equivalent to £200 in 2023)[28] to cut a 12" master. George Harrison attended the launch party, along with Pete Ham of Badfinger and Klaus Voormann.[55]

The studio became a second home for Apple Records artists, although they also used Abbey Road and other studios in London, including Trident Studios, AIR Studios, Morgan Studios and Olympic Studios or elsewhere. The only Beatle solo release to use Apple Studio for a significant portion of its production was Harrison's Living in the Material World album of 1973, yet most of the recording is thought to have taken place at his Friar Park studio.[56]

The first projects to be carried out there after the re-opening were the recording of Lon & Derrek Van Eaton's Brother album,[54] and overdubbing and mixing on Badfinger's Straight Up.[57] Other artists such as Fanny,[58] Harry Nilsson, Nicky Hopkins, Wishbone Ash, Viv Stanshall, Stealers Wheel, Lou Reizner, Clodagh Rodgers and Marc Bolan (as shown in the movie Born To Boogie) also worked there. Apple Studio ceased operations on 16 May 1975.

Legal battles

[edit]Apple Corps v. Apple Computer

[edit]In 1978, Apple Records filed suit against Apple Computer (now Apple Inc.) for trademark infringement. The suit was settled in 1981 with the payment of $80,000 ($268,111 in 2023[59]) to Apple Corps. As a condition of the settlement, Apple Computer agreed to stay out of the music business. A dispute subsequently arose in 1989 when Apple Corps sued, alleging that Apple Computer's machines' ability to play back MIDI music was a violation of the 1981 settlement agreement. In 1991 another settlement, of around $26.5 million, was reached.[60][61] In September 2003, Apple Computer was again sued by Apple Corps, this time for introducing the iTunes Music Store and the iPod, which Apple Corps asserted was a violation of Apple's agreement not to distribute music. The trial opened on 29 March 2006 in the UK,[62] and in a judgement issued on 8 May 2006, Apple Corps lost the case.[61][63]

On 5 February 2007, Apple Inc. and Apple Corps announced a settlement of their trademark dispute under which Apple Inc. took ownership of all of the trademarks related to "Apple" (including all designs of the famed "Granny Smith" Apple Corps Ltd. logos),[64] and licensed certain of those trademarks back to Apple Corps for their continued use. The settlement ended the ongoing trademark lawsuit between the companies, with each party bearing its own legal costs, and Apple Inc. continued using its name and logos on iTunes. The settlement includes terms that are confidential.[65][66] Apple Computer later relied on the Beatles' first use in 1968 to establish ownership and priority of the trademark APPLE MUSIC prior to a 1985 use by a musician of APPLE JAZZ for musical concerts.[67]

The website for Harmonix's The Beatles: Rock Band video game was the first evidence of the Apple, Inc./Apple Corps Ltd. settlement: "Apple Corps" is prominently referred to throughout, and the "Granny Smith" Apple logo appears but the text beneath the logo now reads "Apple Corps" rather than the previous "Apple". The website's acknowledgements specifically state that "'Apple' and the 'Apple logo' are exclusively licensed to Apple Corps Ltd".

On 16 November 2010, Apple Inc. launched the Beatles' entire catalogue in the iTunes Store.[68]

Apple versus EMI

[edit]The Beatles alleged in a 1979 lawsuit that EMI and Capitol had underpaid the band by more than £10.5 million. A settlement was reached in that case in 1989, which granted the band an increased royalty rate and required EMI and Capitol to follow more stringent auditing requirements.[69] In a case beginning in 2005, Apple, on behalf of the surviving Beatles and relatives of the band's late members, again sued EMI for unpaid royalties.[69][70] The case was settled in April 2007 with a "mutually acceptable" conclusion, which remained confidential.[25]

Apple versus Nike/EMI

[edit]In July 1987, Apple Corps sued Nike Inc, Wieden+Kennedy (Nike's advertisement agency), EMI and Capitol Records for the use of the song "Revolution" in a 1987 Nike commercial. Apple claimed that it was not informed of the use of the song and was not paid for continued use and therefore sued the four companies for $15 million.[71] EMI countered stating that the case was "groundless" to their claim they had the "active support and encouragement of Yoko Ono Lennon," who owns 25% of Apple Corps through Lennon's estate, and was quoted as saying: "[The commercial] is making John's music accessible to a new generation." Apple's lawyer responded by stating that Apple cannot take action unless all four shares are in agreement, meaning that Ono must have supported the idea to take legal action at the moment when the decision was made. Harrison had the following to say about the unauthorised use of Beatles songs for advertisement as well as the importance of this particular case:

Well, from our point of view, if it's allowed to happen, every Beatles song ever recorded is going to be advertising women's underwear and sausages. We've got to put a stop to it in order to set a precedent. Otherwise it's going to be a free-for-all. It's one thing when you're dead, but we're still around! They don't have any respect for the fact that we wrote and recorded those songs, and it was our lives.

On 9 November 1989, the lawsuit was settled out of court. As with previous cases between Apple and EMI, a condition of the settlement was that terms of the agreement would be kept secret. It was suggested, however, by a spokesman of Ono that in the end of a very "confusing myriad of issues" there was a large exchange of money. Nike had also ceased to use the song for advertisement in March 1988.[72]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Brown, Peter; Gaines, Steven (1983). The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of The Beatles. London: Macmillan Publishers. p. 246. ISBN 0-333-36134-2.

- ^ "Most Innovative Companies". Mansueto Ventures LLC. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ a b Cross 2005, p. 152.

- ^ 23 February 1965: The Beatles begin filming Help! in the Bahamas | The Beatles Bible

- ^ Brown & Gaines 2002, p. 117.

- ^ a b Cross 2005, p. 199.

- ^ Groovy Bob: The Life and Times of Robert Fraser by Harriet Vyner, Faber, 317 pp, October 1999, ISBN 0-571-19627-6

- ^ "Lennon & McCartney Interview, The Tonight Show". Beatles Interviews. 14 May 1968. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Granados 2002, p. 6.

- ^ "Apple Corps: General Statements". Beatle Money. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Lennon 1978, p. 146.

- ^ Yesterday: The Beatles Remembered with Martin Roberts, Pan Macmillan (1988), p. 108, ISBN 0-283-99621-8

- ^ Taylor 1988, p. 108.

- ^ Granados, Stefan. Those Were the Days – The Beatles Apple Organization. Cherry Red Records. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Granados, M. Those Were the Days. p. 11.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 191.

- ^ "Paul McCartney: Expenses". Beatle Money. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Granados, M. Those Were the Days. p. 24.

- ^ Carlin 2009, p. 171.

- ^ "Uncontrolled Weirdness". New Internationalist. October 1990. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ a b "John Lennon & Paul McCartney: Apple Press Conference". Beatles Interviews. 14 May 1968. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Clayson & Leigh 2003, p. 256.

- ^ Clayson & Leigh 2003, p. 257.

- ^ Kozinn, Allan (12 April 2007). "Magical Mystery Tour Ends for Apple Corps Executive". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Evans, Jonny (12 April 2007). "EMI, Apple Corps deal good news for iTunes?". MacWorld. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Beatles' friend quits top job at Apple Corps". NME. 10 April 2007. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Blaney 2005, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (3 August 1979). "Alex Mardas". New Statesman.

- ^ "Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to 2007". Measuring Worth. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- ^ Harry Castleman & Walter J. Podrazik, All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975, Ballantine Books (New York, NY, 1976), pp 318–21.

- ^ Miles, Barry (2009). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. Omnibus Press. pp. 655–656. ISBN 978-0-85712-000-7.

- ^ Badman, Keith (2009). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970-2001. Omnibus Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-85712-001-4.

- ^ Tennant & Willis 2008, p. 62.

- ^ Tennant & Willis 2008, p. 125.

- ^ Tennant & Willis 2008, p. 174.

- ^ Tennant & Willis 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Tennant & Willis 2008, p. 170.

- ^ Matovina 2000.

- ^ 94 Baker Street: The Pop Psych Sounds of the Apple Era 67–69. Rpm. 20 October 2003. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ An Apple a Day. Rpm. 10 April 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ Treacle Toffee World: Further Adventures Into the Pop Psych Sounds from the Apple Era 1967–1969. Rpm. 27 October 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ Granados, S. Those Were the Days. p. 44

- ^ Yesterday by Robert Freeman

- ^ Many Years From Now by Miles, In My Life by Pete Shotton

- ^ The Complete EMI Recording Sessions by Mark Lewisohn

- ^ The Beatles London by Mark Lewisohn and Peter Schreuder.

- ^ Granados, S. Those Were the Days. p. 76

- ^ Blaney 2005, p. 15.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 218.

- ^ a b Cross 2005, p. 239.

- ^ a b Cross 2005, p. 238.

- ^ "When Savile Row was FAB for the Beatles". Savile Row Style. Savile Row Style Magazine. 27 January 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ a b Apple US press release for Lon & Derrek Van Eaton's Brother album, September 1972. Retrieved 24 February 2012,

- ^ Keith Badman, The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001, Omnibus Press (London, 2001), p. 50.

- ^ Simon Leng, While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison, Hal Leonard (Milwaukee, WI, 2006), p. 126.

- ^ Badman, The Beatles Diary Volume 2, p. 50.

- ^ Fanny Hill (Media notes). Reprise Records. 1972. K 44174.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Borland, John; Fried, Ina (23 September 2004). "Apple vs. Apple: Perfect harmony?". CBS Interactive. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ a b "Apple Corps v Apple Computer: judgment in full". The Times. 8 May 2006. p. 1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Apple giants do battle in court". BBC. 29 March 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Apple Computer Triumphs In Beatle Case". Billboard. 8 May 2006. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Malley, Aidan; Jade, Kasper (12 April 2007). "Apple Inc. scores trademark coup with Beatles' label logos". Apple Insider. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Kerris, Natalie. "Apple Inc. and the Beatles' Apple Corps Ltd. Enter into New Agreement" (Press release). Apple Inc. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Sweney, Mark (5 February 2007). "Apple trademark dispute resolved". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Charles Bertini v. Apple, Inc., 2021 WL 1575580 (UJSP{TO Trademark Trial and Appeal Board 2021)

- ^ Sabbagh, Dan; Arthur, Charles (16 November 2010). "The Beatles and Apple finally come together, right now… on iTunes". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Beatles sue EMI in royalties row". BBC. 16 December 2005. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Beatles to sue EMI for millions in royalties". The Times. 31 August 2006. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Nike & The Beatles". The Pop History Dig, LLC. 11 November 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Nike Was Sued For 1987 Commercial That Used The Beatles "Revolution" Without Apple Records Permission". Feel Numb. 31 August 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

References

[edit]- Blaney, John (2005). John Lennon: Listen To This Book. Paper Jukebox. ISBN 978-0-9544528-1-0.

- Brown, Peter; Gaines, Steven (2002). The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of the Beatles. NAL Trade; Reprint edition. ISBN 978-0-451-20735-7.

- Clayson, Alan; Leigh, Spencer (2003). The Walrus Was Ringo: 101 "Beatles" Myths Debunked. Chrome Dreams. ISBN 978-1-84240-205-4.

- Carlin, Peter Ames (2009). Paul McCartney: A Life. JR Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-906779-64-1.

- Cross, Craig (2005). Beatles-discography.Com: Day-by-Day Song-by-Song Record-by-Record. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-31487-4.

- DiLello, Richard (1973). The Longest Cocktail Party. Charisma Books. ISBN 978-0-85947-006-3.

- Frontani, Michael R. (2007). The Beatles: Image and the Media. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-966-8.

- Granados, Stefan (2002). Those Were the Days: An Unofficial History Of The Beatles' Apple Organization: An Unofficial History of the "Beatles" Apple Organization 1967–2001. Cherry Red Books. ISBN 978-1-901447-12-5.

- Linzmayer, Owen (2004). Apple Confidential 2.0: The Definitive History of the World's Most Colorful Company: The Real Story of Apple Computer, Inc. No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-59327-010-0.

- Lennon, Cynthia (1978). A Twist of Lennon. Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-352-30196-3.

- Matovina, Dan (2000). Without You: The Tragic Story of "Badfinger". Frances Glover Books. ISBN 978-0-9657122-2-4.

- McCabe, Peter; Schonfeld, Robert D. (1973). Apple to the Core: Unmaking of the "Beatles". Sphere Books. ISBN 978-0-7221-5899-9.

- Onkvisit, Sak; Shaw, John (2008). International Marketing: Analysis and Strategy: Strategy and Theory. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77261-7.

- Taylor, Alistair (1988). Yesterday: "Beatles" Remembered. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0-283-99621-4.

- Tennant, Paul; Willis, John (2008). All You Need Is Luck...: How I Got a Record Deal by Meeting Paul McCartney. Happy About. ISBN 978-1-60005-111-1.

External links

[edit]- The complete Apple Records

- Beatles Ltd. at Companies House ("Filing History" tab includes the original foundation and renaming documents)

- Overview of Beatles companies