Anti-lynching movement

| Anti-lynching movement | |

|---|---|

| Part of the nadir of American race relations | |

Marchers in the Silent Parade. | |

| Date | 1890s-1930s (height) |

| Location | |

| Caused by | Lynching in the United States |

| Goals |

|

| Methods |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

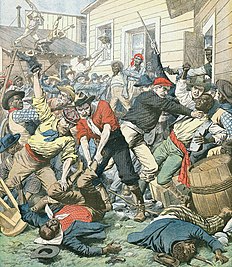

The anti-lynching movement was an organized political movement in the United States that aimed to eradicate the practice of lynching. Lynching was used as a tool to repress African Americans.[1] The anti-lynching movement reached its height between the 1890s and 1930s. The first recorded lynching in the United States was in 1835 in St. Louis, when an accused killer of a deputy sheriff was captured while being taken to jail. The black man named Macintosh was chained to a tree and burned to death. The movement was composed mainly of African Americans who tried to persuade politicians to put an end to the practice, but after the failure of this strategy, they pushed for anti-lynching legislation. African-American women helped in the formation of the movement,[2] and a large part of the movement was composed of women's organizations.[3]

The first anti-lynching movement was characterized by black conventions, which were organized in the immediate aftermath of individual incidents. The movement gained wider national support in the 1890s. During this period, two organizations spearheaded the movement—the Afro-American League (AAL) and the National Equal Rights Council (NERC).[3]

The first anti-lynching bill was the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill introduced in the 65th United States Congress by Representative Leonidas C. Dyer, a Republican from St. Louis, Missouri. The Dyer bill was re-introduced in subsequent sessions of Congress, but its passage was blocked in the Senate by a filibuster by Southern Democrats, and was never enacted. On January 4, 1935, Democratic Senators Edward P. Costigan and Robert F. Wagner together set out a new bill, the Costigan-Wagner Bill, that stated: "To assure to persons within the jurisdiction of every state the equal protection of the crime of lynching." The bill had many protections from all types of lynching.[4] In March 2022, the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, banning the practice and classifying it as a hate crime, passed both houses of Congress and was signed into law by President Joe Biden on March 29, 2022.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

[edit]In 1909, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was established. The NAACP formed a special committee in 1916 in order to push for anti-lynching legislation and to enlighten the public about lynching.[3] This organization's purpose was to ensure that African Americans got their economic, political, social, and educational rights. The NAACP used a combination of tactics such as illegal challenges, demonstrations, and economic boycotts.

The NAACP youth were part of many rallies. They attended many protests against lynching and wore black in memory of all who had been murdered. They also sold anti-lynching buttons to raise money for the NAACP. The money they raised was to keep the fight against lynching going. They sold a huge number of buttons that said "Stop Lynching" and made about $869.25. The youth also contributed by having demonstrations to raise awareness about the horrors of lynching. They had these demonstrations in seventy-eight different cities all over the United States.[5]

According to Noralee Frankel, the anti-lynching movement originated during the Reconstruction era, following the Civil War. It cannot be described only as a result of the reforms during the Progressive Era.[6]

Women's contributions

[edit]Many women contributed to the anti-lynching movement through the Dyer Bill, including Ida B. Wells, Mary Burnett Talbert and Angelina Grimké. The bill exposed both lynching and the effects it had on the people.

Ida B. Wells

[edit]Ida B. Wells was a significant figure in the anti-lynching movement. After the lynchings of her three friends, she condemned the lynchings in the newspapers Free Speech and Headlight, both owned by her. Wells wrote to reveal the abuse and race violence African Americans had to go through. She was a prominent member of many civil rights organizations, such as the NAACP, the Niagara Movement, and the Afro-American Council.[7] Wells encouraged black women to work for anti-lynching laws to be passed. She was also part of the “First Suffrage Club for Black Women."[8] Ida B. Wells asked “Is Rape the ‘Cause’ of Lynching?” in their circular titled “The Shame of America,” that emphasized the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, when they were in the Anti-Lynching Campaigns. Wells drew attention to the number of 83 women being lynched in a time frame of 30 years in addition to the 3,353 men who were also lynched.[9] Because of her anti-lynching campaigning she received death threats from racist rioters.[3] In 1892, she published the editorial "Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases," in which she was deeply critical of the South's relationship with lynching. She said the following:

Nobody in this section of the country believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men rape white women. If Southern white men are not careful, they will overreach themselves and public sentiment will have a reaction; a conclusion will then be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.[10]

Having insulted white women's morality, the reaction in her hometown of Memphis was particularly violent; her newspaper was looted and burned down, and her co-owners were run out of town. Wells had been in the North when the editorial was published and was forced to remain in the North due to threats that she would be lynched if she returned to Memphis.[11] After having her children she got out of the organizations but she kept on protesting against lynching. In 1899 she protested the Sam Hose lynching in Georgia.

Mary Burnett Talbert

[edit]Mary B. Talbert was a civil rights and anti-lynching activist, preservationist, international human rights proponent, and educator. She was born and raised in Oberlin, Ohio. She was the president of the National Association of Colored Women from 1916 to 1920. In 1923 she became vice president of the NAACP, and her last contribution was leading the Anti-Lynching Crusaders during the anti-lynching movement.[12] In 1922 Talbert and other African American women among the Anti-Lynching Crusaders raised $10,000 for the NAACP.[13]

Angelina Weld Grimké

[edit]Angelina Weld Grimké, niece of the white Angelina Grimké, was a New Negro poet and often wrote about the effects of lynching. In one of her most famous plays, Rachel, she addressed both the lynching problem and the psychological affects that it had on African American people.[14] This anti-lynching play was first performed before the NAACP's Anti-lynching Drama Committee. One of Grimké's main goals was to get White women to empathize with the Black women who witnessed the lynching of their husbands and children.[15]

Juanita Jackson Mitchell

[edit]Juanita Jackson was employed by the NAACP as their national youth director. Mitchell did everything she could to get young people involved in the NAACP and protesting against lynching. She got the young to campaign for anti-lynching legislation. She also got to send anti-lynching messages through a radio broadcast: in 1937 Juanita Jackson convinced the National Broadcasting Company to broadcast fifteen minutes on the need for anti-lynching laws.[16]

Anti-Lynching Crusaders

[edit]The Anti-Lynching Crusaders were a group of women dedicated to stopping the lynching of African Americas. Before the Anti-Lynching Crusaders was founded all these group of Crusaders were involved with churches that helped them learn how to lead with gender problems and power.[9] The organization was under the guidance of the NAACP and was founded in 1922. The Crusaders women organization started with sixteen members but grew to nine hundred members within three months.[9] This organization focused specifically on raising money to pass the Dyer Bill and stopping the killings of innocent people.[17] Mary Talbert was the leader of the group; her objective was to unite 700 state workers, specifically women, but of no distinguishing color or race. Talbert was an active fundraiser for the Crusaders and affirmed the organizations desire "to raise at least one million dollars...to help us put over the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill."[9] They raised over $10,800 by the spring of 1923.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Cedric J. Robinson (February 20, 1997). Black Movements in America. Psychology Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-415-91222-8. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Lynne E. Ford (2008). Encyclopedia of Women and American Politics. Infobase Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4381-1032-5. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Paul Finkelman (November 2007). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-First Century. Oxford University Press. pp. 78–82. ISBN 978-0-19-516779-5. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Walter, David O. (June–July 1935). "Previous Attempts to Pass a Federal Anti-Lynching Law". Congressional Digest. 14 (6/7): 169–171 – via EBSCOhost.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bynum, Thomas (2013). NAACP Youth and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1936–1965. University of Tennessee Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-57233-982-8.

- ^ Noralee Frankel (December 22, 1994). Gender, Class, Race, and Reform in the Progressive Era. University Press of Kentucky. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8131-0841-4. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Paul Finkelman (November 2007). Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-First Century. Oxford University Press. pp. 78–82. ISBN 978-0-19-516779-5. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ "Woman Journalist Crusades Against Lynching". Library of Congress. December 10, 1998. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Zackodnik, Teresa (2011). Press, Platform, Pulpit: Black Feminist Publics in the Era of Reform. United States of America: The University of Tennessee Press/Knoxville. p. 4.

- ^ Wells-Barnett, Ida B. "Southern Horrors: Lynch Law In All Its Phases". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved November 22, 2022.

- ^ Giddings, Paula (1984). When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America. Harper Collins. p. 29. ISBN 978-0688146504.

- ^ Williams, Lillian (1999). Strangers in the Land of Paradise: Creation of an African American Community, Buffalo New York. Blooming IN: Indiana University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0253335524.

- ^ Morgan, Francesca (2005). Women and Patriotism in Jim Crow America. p. 148.

- ^ Rucker and Upton, Walter and James (November 30, 2006). Encyclopedia of American Race Riots, Volume 1. Greenwood. p. 64. ISBN 978-0313333019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Brown- Guillory, Elizabeth (1996). Women of Color: Mother-Daughter Relationships in 20th-Century Literature. University of Texas Press. pp. 191. ISBN 978-0-292-70847-1.

- ^ Bynum, Thomas (2012). NAACP Youth and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1936–1965. University of Tennessee Press. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-1-57233-982-8.

- ^ Rucker, Walker (2007). ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AMERICAN RACE RIOTS. Greenwood Press. p. 64.

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Mary Jane. "Advocates in the Age of Jazz: Women and the Campaign for the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill." Peace & Change 28.3 (2003): 378–419.

- Brundage, William Fitzhugh, ed. Under sentence of death: Lynching in the South (UNC Press Books, 1997) [1].

- Cooper, Melissa. "Reframing Eleanor Roosevelt’s Influence in the 1930s Anti-Lynching Movement around a 'New Philosophy of Government'." European journal of American studies 12.12-1 (2017). online

- Greenbaum, Fred. "The Anti-Lynching Bill of 1935: The Irony of ‘Equal Justice—Under Law.’." Journal of Human Relations 15.3 (1967): 72–85.

- Hishida, Sachiko. "The hope and failure in interracial cooperation: a study of the anti-lynching movement in the 1930s." Journal of American and Canadian Studies 23 (2005): 77–95.

- Hutchinson, Earl Ofari. Betrayed: A history of presidential failure to protect Black lives (Routledge, 2019) online.

- Miller, Robert Moats. "The Protestant churches and lynching, 1919-1939." Journal of Negro History 42.2 (1957): 118–131. online; argues that the record was mixed but their concern was deep and widespread.

- Rable, George C. "The South and the Politics of Antilynching Legislation, 1920-1940." Journal of Southern History 51.2 (1985): 201–220. online

- Ray Teel, Leonard. "The African-American Press and the Campaign for a Federal Antilynching Law, 1933–34: Putting Civil Rights on the National Agenda." American Journalism 8.2-3 (1991): 84–107. doi.org/10.1080/08821127.1991.10731334

- Royster, Jacqueline Jones. Southern Horrors and Other Writings: The Anti-Lynching Campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892-1900 (2nd ed. 2016) excerpt

- Washington, Deleso Alford. "Exploring the Black Wombman's Sphere and the Anti-Lynching Crusade of the Early Twentieth Century." Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law 3 (2001): 895+. online

- Ziglar, William L. "The decline of lynching in America." International Social Science Review (1988): 14–25. online